I was dining--alone, as I now always did--at the Pink Adobe in Santa Fe. I’d heard that Sam Shepard ate there regularly when he was living in town and, since I liked his stuff well enough, I was hoping some of the inspiration would rub off on me. It had been some time since I’d come up with anything usable—at least anything I’d dare show anyone—and I was getting desperate. Actually, I was desperate in more ways than just that one. Awhile back all of my moorings had been cut and since then I’d been staying out in the desert, moving from one town to the next as boredom or panic dictated. Mostly I’d been staying on the outskirts of slightly-seedy, sand-choked little towns like Winslow, AZ, Española, NM, and Elko, NV. But for the last few days I’d gone a bit upscale.

I’d actually begun to think that being monolingual was my main problem. Aside from the ubiquitous Spanish, all around me I heard Russian, French, German, and even ancient Indian dialects that tribal law stated could not be written down or recorded. It had occurred to me that, for the first time in my life, English was failing me and perhaps these other languages contained the words I wanted. But then I figured that the language required to say whatever it was I thought I needed to say probably didn’t even exist and, anyway, I was certainly in no shape to invent it.

I was mulling over these and other similar thoughts, feeling suitably dour as I worked at my enchiladas, when I noticed a boy and girl through the window. Or, rather, I noticed the girl. Chestnut brown hair, black leather coat, dark blue wool skirt, and light grey stockings. As I watched her talk to this boy I became transfixed. She seemed very serious and did not smile, although he occasionally did. I watched them for some time until I had finished my meal and paid for it.

I walked across the Old Santa Fe Trail, looking at the girl as I did. Our eyes met and I held my glance a beat longer than would be usual, then walked up the steps to the San Miguel Mission. I stood out front of the old church and looked down on the couple. To give myself cover, every now and then I pretended to check my watch and look impatiently up and down the street. After a short time the two embraced and, as the girl rested her head on the boys shoulder, she looked directly at me. I held her stare and could see that her eyes, seeming now to me quite willful, were a soft grey, the same color as her stockings. Very nice, I thought. But was the boy a friend, brother, or lover? Not that I really cared. A guy I knew once said that boyfriends are a little like herpes: they tend to go away for awhile. Of course, that guy was dead now and I never had been able to find out just what had happened, although I'd been told a gun had been involved.

The two parted and I watched the girl walk down the street and go into a coffee shop. I thought for a moment. I knew that if I went after her, regardless of what happened or did not happen—because, let’s face it, nothing in this world is a sure thing—I’d hate myself for it. Then again, self-hatred was an emotion I’d recently taken to cultivating nearly to the exclusion of all others. I think it was probably right then that a series of events was put into motion that I would indeed come to dearly regret. Yet I hesitated and for a brief instant on that cool, clear fall day, another face flickered warmly in my mind. Quickly I pushed it away and thought again of those soft grey eyes before starting down the road. (CONTINUED)

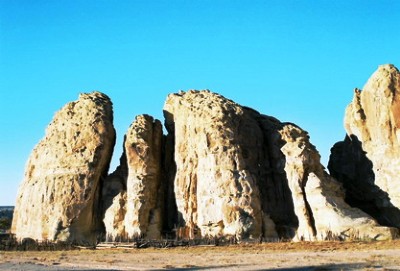

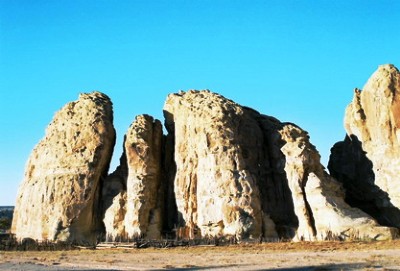

I know, photos of Santa Fe, NM would've probably made more sense here, but instead it's more shots from Acoma Pueblo, Sky City, NM. Well, except the bottom one, which is Petrified Forest National Park, AZ.

Shelly and I are at the Waffle House. It’s early and we’ve been up all night. There are a number of reasons why we haven't slept. All of them are bad. Shelly’s staring at me bleary-eyed and anxious. She’s wearing the same blue dress she wore yesterday. It’s a dress I used to love seeing her in. And taking her out of. But right now I’m feeling damp and wrung-out and sick to my stomach.

Our waitress comes over to take our order. She’s young and nervous and her name is Danielle. I guess that it’s her first day. Shelly orders coffee, two eggs, and toast. There is no cheer in her voice, only fear and exhaustion, like sandpaper, catching at her throat, each word a brittle, dead leaf. I try to sound pleasant, like me and Shelly are just two people out for a normal breakfast, while I order a pecan waffle. But as soon as I say the words the thought of butter and syrup and fried batter makes me want to retch.

When Danielle flips her hand over to write on the order pad I see two thick scars across her right wrist—widthwise, not lengthwise. Whether these cuts then were simply a cry for attention or the result of a fundamental lack of understanding as far as the basics of physiology go I cannot say. In any case, Danielle smiles perkily and says, “Be right up, ‘kay guys?!”

Danielle’s departure leaves Shelly and me in silence. I try to think of something to say but nothing comes to mind. For hours, Shelly has been telling me things that I’ve tried to convince her are simply not true. In response, she’s told me that truth, once and for all, now has to be the same for both of us. Just before we came into the restaurant I’d said that I didn’t think truth could ever be exactly the same for any two people. She just looked at me and said, “You make me sad.” It was difficult for me to admit that, right there, might indeed have been a solid truth, cold, objective, and utterly removed from any necessity of interpretation.

I hear Danielle call the woman at the hash brown station “mom” just as a man steps to the counter. A waitress tells him he can sit anywhere, but the man only shakes his head nervously and mumbles something I don’t understand. The waitress seems startled and the man says something that sounds to me like “cowboy.” He starts to fidget. The waitress frowns. “What’s that, hon’?” she asks. “Comfrey,” he replies. The waitress is silent. I realize that the man is retarded, though probably only mildly, and it’s not immediately obvious. I turn to Shelly, but she has also begun to follow the exchange. “Commie,” says the man quietly. The woman looks to another waitress for help, but the other waitress only smiles, making the woman giggle a little.  The man notices this, closes his eyes tightly, as if it was difficult, then opens them and screams, “Collie! Collie! Collie!” The restaurant goes dead quiet. Everyone turns to look. Seconds pass. Waffles begin to burn. Hashbrowns go unsmothered and uncovered. “Collie!” he screams again and, with his balled right hand, begins to punch himself in the face. Four, five, six times the man strikes himself, in the cheek, the mouth, the eye. Finally, he pulls his fist back one last time but, instead of hitting himself, he throws a handful of change at the counter. Coins explode through the kitchen and dining area, so many that he must’ve been intending to pay mostly in pennies. In tears, the man points to a mug and says, “Cobby!” The waitress is stunned. “Coffee?” she whispers. Tears flow down the man’s face. Thick red welts have risen on his forehead. “Yuh!” he yells, but turns to leave the restaurant. As he exits the door he punches the frame and screams again, then runs across the parking lot, around a truck, and out of view.

The man notices this, closes his eyes tightly, as if it was difficult, then opens them and screams, “Collie! Collie! Collie!” The restaurant goes dead quiet. Everyone turns to look. Seconds pass. Waffles begin to burn. Hashbrowns go unsmothered and uncovered. “Collie!” he screams again and, with his balled right hand, begins to punch himself in the face. Four, five, six times the man strikes himself, in the cheek, the mouth, the eye. Finally, he pulls his fist back one last time but, instead of hitting himself, he throws a handful of change at the counter. Coins explode through the kitchen and dining area, so many that he must’ve been intending to pay mostly in pennies. In tears, the man points to a mug and says, “Cobby!” The waitress is stunned. “Coffee?” she whispers. Tears flow down the man’s face. Thick red welts have risen on his forehead. “Yuh!” he yells, but turns to leave the restaurant. As he exits the door he punches the frame and screams again, then runs across the parking lot, around a truck, and out of view.

There is no way to restore normalcy to the Waffle House. A man puts some bills on the counter and rises, most of his meal uneaten. Then another couple leaves. Still no one speaks. I turn to Shelly, but she is already getting up, the tears already beginning. I look at Danielle, but she is frozen, her mouth hanging open, as a few other waitresses begin to talk amongst themselves and a cook scrapes seared eggs off the skillet. I motion to Danielle, but she does not see me. So, I pay for our food, the food we never even saw. It’s just as well, I think. I didn’t want to eat anyway. I leave a nice tip for Danielle in the hope that she’ll show up for work again tomorrow morning. But tomorrow morning is a long way off and there are other tragedies to attend to, so I head off into the glimmering sunlight after Shelly.

All photos are from Acoma Pueblo, Sky City, New Mexico. The top three are from on top of the sandstone mesa, about 400 feet high. The community has been occupied for several hundred years and remains so to this day.

The man notices this, closes his eyes tightly, as if it was difficult, then opens them and screams, “Collie! Collie! Collie!” The restaurant goes dead quiet. Everyone turns to look. Seconds pass. Waffles begin to burn. Hashbrowns go unsmothered and uncovered. “Collie!” he screams again and, with his balled right hand, begins to punch himself in the face. Four, five, six times the man strikes himself, in the cheek, the mouth, the eye. Finally, he pulls his fist back one last time but, instead of hitting himself, he throws a handful of change at the counter. Coins explode through the kitchen and dining area, so many that he must’ve been intending to pay mostly in pennies. In tears, the man points to a mug and says, “Cobby!” The waitress is stunned. “Coffee?” she whispers. Tears flow down the man’s face. Thick red welts have risen on his forehead. “Yuh!” he yells, but turns to leave the restaurant. As he exits the door he punches the frame and screams again, then runs across the parking lot, around a truck, and out of view.

The man notices this, closes his eyes tightly, as if it was difficult, then opens them and screams, “Collie! Collie! Collie!” The restaurant goes dead quiet. Everyone turns to look. Seconds pass. Waffles begin to burn. Hashbrowns go unsmothered and uncovered. “Collie!” he screams again and, with his balled right hand, begins to punch himself in the face. Four, five, six times the man strikes himself, in the cheek, the mouth, the eye. Finally, he pulls his fist back one last time but, instead of hitting himself, he throws a handful of change at the counter. Coins explode through the kitchen and dining area, so many that he must’ve been intending to pay mostly in pennies. In tears, the man points to a mug and says, “Cobby!” The waitress is stunned. “Coffee?” she whispers. Tears flow down the man’s face. Thick red welts have risen on his forehead. “Yuh!” he yells, but turns to leave the restaurant. As he exits the door he punches the frame and screams again, then runs across the parking lot, around a truck, and out of view.