We’ve added another member to the crew, Jason, and his first day is a tough one. The haul up the first mountain is long and steep. Then we go back down. Then we start back up again. I walk a bit ahead and as the day progresses my lead increases. Jason is a smoker, but assures me that within a week he’ll be “battle hardened”; little do we know that it won’t take him nearly that long. As we start our final ascent of the day Jason stops and gasps, “I’ve gotta take a fiver.” I’m about 40 feet in front (and 20 feet above) him, so I sit on a nearby rock and wait. I’m not concerned. I figure he’ll do okay--at least as well as anyone else could be expected to do.

After a few minutes we start up again. When we reach the top of the mountain Jason looks a little peaked. I almost feel a pang of worry, but it quickly passes. The concern I feel for Allison, on the other hand, is steadily growing. She has developed a rash on the back of her leg and has been having trouble sleeping. She’s also been having headaches and experiencing joint pain. I’ve told her that she needs to get checked for Lyme disease as soon as we get back to Knoxville. She's replied, with all the confidence she can muster, that she knows she doesn’t have Lyme disease and will be fine. I ask her to go anyway. In the meantime, we’ve given her the easiest transects, usually the ones closest to the vehicle. On this day, therefore, she’s finished long before us and has been sleeping in the bed of the truck for the last couple hours.

After a few minutes we start up again. When we reach the top of the mountain Jason looks a little peaked. I almost feel a pang of worry, but it quickly passes. The concern I feel for Allison, on the other hand, is steadily growing. She has developed a rash on the back of her leg and has been having trouble sleeping. She’s also been having headaches and experiencing joint pain. I’ve told her that she needs to get checked for Lyme disease as soon as we get back to Knoxville. She's replied, with all the confidence she can muster, that she knows she doesn’t have Lyme disease and will be fine. I ask her to go anyway. In the meantime, we’ve given her the easiest transects, usually the ones closest to the vehicle. On this day, therefore, she’s finished long before us and has been sleeping in the bed of the truck for the last couple hours.

As Jason stumbles wearily up the dirt road I see Carl on a deer stand—more like a deer platform—that someone has built way up in a high-tension tower. He waves and it looks like he’s having fun, so I stop and once he comes down I go up. At the top the platform (a piece of wood simply laid across a corner angle) is small and the footing precarious. It’s a very long way down. I wonder for a moment what hunter would be crazy enough to sit up here with a gun waiting for a deer to pass by below. Then I quickly realize there’s plenty of ‘em. Hell, now I’m up here too.

Alright, there's a little photo trickery here. The first and third shots are from Hamilton County, not Marion. That middle photo is from inside a coal mine in Sequatchie County. Did you know you can die from going in old coal mines? The culprit is known as "black damp." We'll get to that later.

“We’re drillin’”, the man says, and a jet of muddy tobacco juice spews from his crooked mouth and lands at his feet. The statement is wrong on any number of levels. We’ve pulled beside a well-punching rig and four or five tough-looking customers are standing around. Their pick-up trucks are in the road and one of the larger ones is completely blocking our path. The men are smoking, talking, staring at the ground, but certainly not drillin'. Frankly, we don’t care what they do, as long as they let us by. But, so far, “We’re drillin’” is all anybody will say to us. So we wait in the idling truck and look at each other, wondering how this will play out.

As it happens, it plays out rather prosaically when, after a couple minutes of nothing much, an older man finally breaks away from the group and moves the truck from the road. We wave slightly as we pass and I watch in the rearview mirror as the men re-group. Carl resumes navigating.

Not many days afterward we meet Ricky, one of the drilling team, as he’s driving up a dirt road that we’re using to start that morning’s surveys. He gives us his cell phone number in case we need help—this has become a running theme—and tells us that at the very top of Aetna Mountain lives a family with two teenaged daughters. “They have no electricity,” he says. “How they get their water is anyone’s guess.” On top of the mountain is a long way from anywhere; there certainly aren’t any neighbors to get in the way. For the rest of our time in this place we will hope for a glimpse of what quickly becomes known as the “unknown family.” We believe that we see the mother and father on two occasions going slowly up the mountain in their red S-10. They do not seem happy to see us on either encounter. But it is the daughters we really want to run across, mountain nymphs tripping through dewy meadows in luminescent nightgowns. Perhaps chasing a fawn through the woods as they dance and sing, wildflowers wound into their flowing tresses. Certainly these Southern sirens would lead well-drillers and forest surveyors alike to their ultimate doom. Well, it does get tedious walking through the woods everyday and the mind tends to wander.

Not many days afterward we meet Ricky, one of the drilling team, as he’s driving up a dirt road that we’re using to start that morning’s surveys. He gives us his cell phone number in case we need help—this has become a running theme—and tells us that at the very top of Aetna Mountain lives a family with two teenaged daughters. “They have no electricity,” he says. “How they get their water is anyone’s guess.” On top of the mountain is a long way from anywhere; there certainly aren’t any neighbors to get in the way. For the rest of our time in this place we will hope for a glimpse of what quickly becomes known as the “unknown family.” We believe that we see the mother and father on two occasions going slowly up the mountain in their red S-10. They do not seem happy to see us on either encounter. But it is the daughters we really want to run across, mountain nymphs tripping through dewy meadows in luminescent nightgowns. Perhaps chasing a fawn through the woods as they dance and sing, wildflowers wound into their flowing tresses. Certainly these Southern sirens would lead well-drillers and forest surveyors alike to their ultimate doom. Well, it does get tedious walking through the woods everyday and the mind tends to wander.

I wonder what the unknown family does in the winter when the roads get icy and there’s no way down the mountain for days at a time. Ricky shakes his head mournfully. “I just hope those girls survive,” he says. “I just hope they can make it through.”

Well, so much for one post a week. I won't make promises like that again since I know I can't keep 'em. I guess I'll just post when I can. I am an irresponsible blogger.

“We can’t go forward! We can’t go down! We can’t go up! We can only go back!” My radio call to Carl captures our predicament fairly succinctly. Above us is a series of vertical bluffs. In front of us is a waterfall. Below us is a steep drop to a rocky creek. Allison is annoyed, but can hardly argue with my assessment. Carl just laughs and wishes us luck; he’s already on top of his own set of bluffs. Defeated, we begin the long ascent up the valley, back the way we came.

Later we go to Lookout Mountain for dinner at the Lookout Mountain Café. Afterwards we go to Point Park, but since we can’t scrape together the $6 entrance fee between the three of us, we have to turn around. A representative of the National Park Service has been watching us from his truck, lest we jump the gate. As we pass his vehicle he asks us what we’re doing in the area, a presumptuous question. At first he doesn’t believe us when we tell him we’re walking Aetna Mountain. He laughs and asks if we’re using the trails. We tell him, “No, we just go in and start walking.” He laughs again and asks us how far down we go. “All the way to the bottom,” we reply, “to the creek beds.” He stops and raises his eyebrows, suddenly serious. “Really?” he says. “Let me give you my card.”

Donald “Cavewolf” Connor moved to Chattanooga for the caves. He tells us he does 300 foot drops in caves, sometimes spending nine hours in the descent. He also dives, though he will not enter totally submerged caverns. He asks us if we’ve seen any caves, but we have not. He says we might come across a “blower,” a cave that funnels air from the ridge down to the valley floor. Air velocity can reach 30 mph and he says we can’t miss one of these things if it’s close. “You’ll feel the wind.” The Chattanooga area apparently has the highest density of caves in the US and Cavewolf would love to know about any we stumble across. Also, it turns out that he’s a member of Chattanooga Cave Search and Rescue and offers us his services if we get stuck. It’s reassuring and not reassuring at all.

Donald “Cavewolf” Connor moved to Chattanooga for the caves. He tells us he does 300 foot drops in caves, sometimes spending nine hours in the descent. He also dives, though he will not enter totally submerged caverns. He asks us if we’ve seen any caves, but we have not. He says we might come across a “blower,” a cave that funnels air from the ridge down to the valley floor. Air velocity can reach 30 mph and he says we can’t miss one of these things if it’s close. “You’ll feel the wind.” The Chattanooga area apparently has the highest density of caves in the US and Cavewolf would love to know about any we stumble across. Also, it turns out that he’s a member of Chattanooga Cave Search and Rescue and offers us his services if we get stuck. It’s reassuring and not reassuring at all.

Cavewolf tells us some other things, including his belief that the listing of mountain skullcap as a federally threatened species is an abuse of the Endangered Species Act. He says that a guy he knows got it listed just to see how easily it could be done. “That plant is everywhere!” Cavewolf spits and we laugh. We haven’t seen a single Scutellaria montana and all we do is look for the thing. We’ve only come as close as its brother, Scutellaria pseudoserrata. Soon, however, we will see evidence that Cavewolf may have been correct.

Cavewolf tells us some other things, including his belief that the listing of mountain skullcap as a federally threatened species is an abuse of the Endangered Species Act. He says that a guy he knows got it listed just to see how easily it could be done. “That plant is everywhere!” Cavewolf spits and we laugh. We haven’t seen a single Scutellaria montana and all we do is look for the thing. We’ve only come as close as its brother, Scutellaria pseudoserrata. Soon, however, we will see evidence that Cavewolf may have been correct.

Over the next couple of weeks we find a few small cave openings, but we don’t tell Cavewolf. Technically, we shouldn’t encourage others to trespass on the property. In any case, we never do find a “blower.” But we never have to call Chattanooga Cave Search and Rescue either.

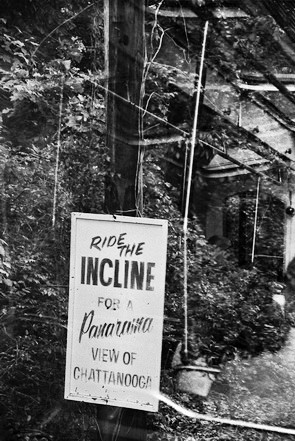

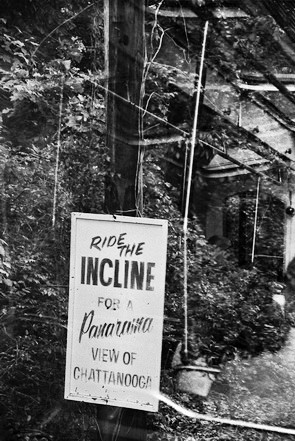

That's a view over Chattanooga at the top and a shot of the inclined railway that can take you there. At the bottom is the real mountain skullcap.

After a few minutes we start up again. When we reach the top of the mountain Jason looks a little peaked. I almost feel a pang of worry, but it quickly passes. The concern I feel for Allison, on the other hand, is steadily growing. She has developed a rash on the back of her leg and has been having trouble sleeping. She’s also been having headaches and experiencing joint pain. I’ve told her that she needs to get checked for Lyme disease as soon as we get back to Knoxville. She's replied, with all the confidence she can muster, that she knows she doesn’t have Lyme disease and will be fine. I ask her to go anyway. In the meantime, we’ve given her the easiest transects, usually the ones closest to the vehicle. On this day, therefore, she’s finished long before us and has been sleeping in the bed of the truck for the last couple hours.

After a few minutes we start up again. When we reach the top of the mountain Jason looks a little peaked. I almost feel a pang of worry, but it quickly passes. The concern I feel for Allison, on the other hand, is steadily growing. She has developed a rash on the back of her leg and has been having trouble sleeping. She’s also been having headaches and experiencing joint pain. I’ve told her that she needs to get checked for Lyme disease as soon as we get back to Knoxville. She's replied, with all the confidence she can muster, that she knows she doesn’t have Lyme disease and will be fine. I ask her to go anyway. In the meantime, we’ve given her the easiest transects, usually the ones closest to the vehicle. On this day, therefore, she’s finished long before us and has been sleeping in the bed of the truck for the last couple hours.

Not many days afterward we meet Ricky, one of the drilling team, as he’s driving up a dirt road that we’re using to start that morning’s surveys. He gives us his cell phone number in case we need help—this has become a running theme—and tells us that at the very top of Aetna Mountain lives a family with two teenaged daughters. “They have no electricity,” he says. “How they get their water is anyone’s guess.” On top of the mountain is a long way from anywhere; there certainly aren’t any neighbors to get in the way. For the rest of our time in this place we will hope for a glimpse of what quickly becomes known as the “unknown family.” We believe that we see the mother and father on two occasions going slowly up the mountain in their red S-10. They do not seem happy to see us on either encounter. But it is the daughters we really want to run across, mountain nymphs tripping through dewy meadows in luminescent nightgowns. Perhaps chasing a fawn through the woods as they dance and sing, wildflowers wound into their flowing tresses. Certainly these Southern sirens would lead well-drillers and forest surveyors alike to their ultimate doom. Well, it does get tedious walking through the woods everyday and the mind tends to wander.

Not many days afterward we meet Ricky, one of the drilling team, as he’s driving up a dirt road that we’re using to start that morning’s surveys. He gives us his cell phone number in case we need help—this has become a running theme—and tells us that at the very top of Aetna Mountain lives a family with two teenaged daughters. “They have no electricity,” he says. “How they get their water is anyone’s guess.” On top of the mountain is a long way from anywhere; there certainly aren’t any neighbors to get in the way. For the rest of our time in this place we will hope for a glimpse of what quickly becomes known as the “unknown family.” We believe that we see the mother and father on two occasions going slowly up the mountain in their red S-10. They do not seem happy to see us on either encounter. But it is the daughters we really want to run across, mountain nymphs tripping through dewy meadows in luminescent nightgowns. Perhaps chasing a fawn through the woods as they dance and sing, wildflowers wound into their flowing tresses. Certainly these Southern sirens would lead well-drillers and forest surveyors alike to their ultimate doom. Well, it does get tedious walking through the woods everyday and the mind tends to wander.

Donald “Cavewolf” Connor moved to Chattanooga for the caves. He tells us he does 300 foot drops in caves, sometimes spending nine hours in the descent. He also dives, though he will not enter totally submerged caverns. He asks us if we’ve seen any caves, but we have not. He says we might come across a “blower,” a cave that funnels air from the ridge down to the valley floor. Air velocity can reach 30 mph and he says we can’t miss one of these things if it’s close. “You’ll feel the wind.” The Chattanooga area apparently has the highest density of caves in the US and Cavewolf would love to know about any we stumble across. Also, it turns out that he’s a member of Chattanooga Cave Search and Rescue and offers us his services if we get stuck. It’s reassuring and not reassuring at all.

Donald “Cavewolf” Connor moved to Chattanooga for the caves. He tells us he does 300 foot drops in caves, sometimes spending nine hours in the descent. He also dives, though he will not enter totally submerged caverns. He asks us if we’ve seen any caves, but we have not. He says we might come across a “blower,” a cave that funnels air from the ridge down to the valley floor. Air velocity can reach 30 mph and he says we can’t miss one of these things if it’s close. “You’ll feel the wind.” The Chattanooga area apparently has the highest density of caves in the US and Cavewolf would love to know about any we stumble across. Also, it turns out that he’s a member of Chattanooga Cave Search and Rescue and offers us his services if we get stuck. It’s reassuring and not reassuring at all. Cavewolf tells us some other things, including his belief that the listing of mountain skullcap as a federally threatened species is an abuse of the Endangered Species Act. He says that a guy he knows got it listed just to see how easily it could be done. “That plant is everywhere!” Cavewolf spits and we laugh. We haven’t seen a single Scutellaria montana and all we do is look for the thing. We’ve only come as close as its brother, Scutellaria pseudoserrata. Soon, however, we will see evidence that Cavewolf may have been correct.

Cavewolf tells us some other things, including his belief that the listing of mountain skullcap as a federally threatened species is an abuse of the Endangered Species Act. He says that a guy he knows got it listed just to see how easily it could be done. “That plant is everywhere!” Cavewolf spits and we laugh. We haven’t seen a single Scutellaria montana and all we do is look for the thing. We’ve only come as close as its brother, Scutellaria pseudoserrata. Soon, however, we will see evidence that Cavewolf may have been correct.