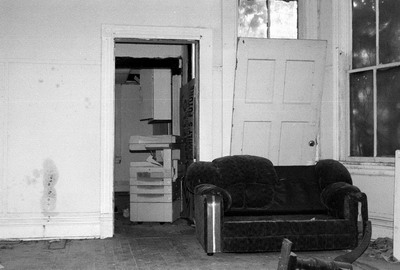

It was almost 10 years that I worked for the county, up until I couldn’t really take it anymore. For all that time I cleaned-out houses that were going to auction after their owners had died without leaving a living relative or specifying a beneficiary. Sometimes I’d show up pretty much right as the medical examiner was loading the body into the ambulance. Other times it took quite awhile to comb through the deceased’s past and determine if they were, for our purposes, at least, alone in this world. Some people talk about immortality as something to be desired but, from what I’ve seen, outliving (or, perhaps, living long enough to alienate) every one of your friends and family is a fate a far sight worse than death.

It was almost 10 years that I worked for the county, up until I couldn’t really take it anymore. For all that time I cleaned-out houses that were going to auction after their owners had died without leaving a living relative or specifying a beneficiary. Sometimes I’d show up pretty much right as the medical examiner was loading the body into the ambulance. Other times it took quite awhile to comb through the deceased’s past and determine if they were, for our purposes, at least, alone in this world. Some people talk about immortality as something to be desired but, from what I’ve seen, outliving (or, perhaps, living long enough to alienate) every one of your friends and family is a fate a far sight worse than death.

You might think that I’d have come across some pretty cool things over the years and, in fact, I was explicitly barred from taking anything for myself from any of the homes I worked. On one occasion, in amongst a stack of worthless albums by the Ray Coniff Singers and Bing Crosby, I found a Blind Lemon Jefferson 78 rpm record. “Bad Luck Blues” on one side and “Broke and Hungry” on the other. I slid the record into the duffel that held my lunch even though I don’t have the equipment to play it.  Another time I found a water-stained photo of Marilyn Monroe signed, “To Petey, Love Always, MM.” I’ve tried to compare the writing against other examples I’ve found on the internet and can’t be sure but it might be authentic. Really, though, most of what was in these houses, the vast, vast majority, was of no use to anyone. Old photo albums, paperbacks, clothes, trinkets of every sort and description; things that mattered only to the decedent. Most of this gets put in black plastic bags and taken to the landfill. Even the Goodwill didn’t want it from us. Furniture that is in nice shape, electronic equipment, appliances, and things of some obvious value are shipped to a warehouse and auctioned off four times a year. You might not think that in a city of this size enough people shuffle off this mortal coil entirely without heir to warrant such an operation. In fact, I was part of a twelve-person team and we struggled not to run a backlog.

Another time I found a water-stained photo of Marilyn Monroe signed, “To Petey, Love Always, MM.” I’ve tried to compare the writing against other examples I’ve found on the internet and can’t be sure but it might be authentic. Really, though, most of what was in these houses, the vast, vast majority, was of no use to anyone. Old photo albums, paperbacks, clothes, trinkets of every sort and description; things that mattered only to the decedent. Most of this gets put in black plastic bags and taken to the landfill. Even the Goodwill didn’t want it from us. Furniture that is in nice shape, electronic equipment, appliances, and things of some obvious value are shipped to a warehouse and auctioned off four times a year. You might not think that in a city of this size enough people shuffle off this mortal coil entirely without heir to warrant such an operation. In fact, I was part of a twelve-person team and we struggled not to run a backlog.

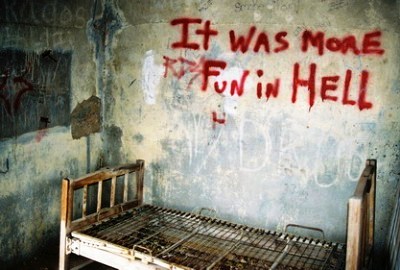

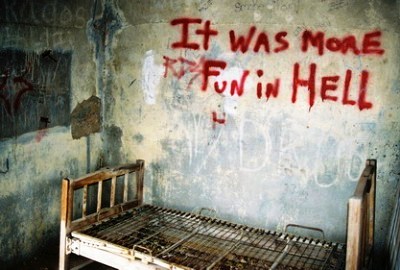

Of course, the first rule of the job is not to get involved. Don’t read the personal correspondence. Don’t try to put meaning to the faces in the pictures. And don’t try to reconstruct the last days or years of the deceased. Remain detached. Keep filling the black plastic bags. It’s hard.  I think most people expect that death will be a passageway from a life well-lived to something even better. Surrounded by our family and friends there will be anxiety and tears, to be sure, but also the warmth given off by a lifetime of memories and the knowledge that, in a very real way, our life continues in those that come after us. Perhaps it is like that for some. But the evidence I’ve seen would indicate that the end of life can also be a long slide into oblivion, the weight of regret hanging heavy as dreams go unfulfilled or collapse in on themselves entirely. When the mind finally can’t cope I guess madness sets in. I often found it something to consider as I tried to not get involved.

I think most people expect that death will be a passageway from a life well-lived to something even better. Surrounded by our family and friends there will be anxiety and tears, to be sure, but also the warmth given off by a lifetime of memories and the knowledge that, in a very real way, our life continues in those that come after us. Perhaps it is like that for some. But the evidence I’ve seen would indicate that the end of life can also be a long slide into oblivion, the weight of regret hanging heavy as dreams go unfulfilled or collapse in on themselves entirely. When the mind finally can’t cope I guess madness sets in. I often found it something to consider as I tried to not get involved.

A good number of the homes I went into were what you might call “garbage houses,” the former occupants having hoarded mountains of worthless material items against a yawning spiritual and emotional void. Old newspapers. Cereal boxes. Children’s toys (despite there apparently having been no children around lately). Bits of yarn. Anything that might be of some use in a future that would never arrive. When it got real bad we had to call in a HAZMAT team. My own father lived in a house somewhat like this. As a boy I recall a mix of anticipation and revulsion as I dug around in drawers looking for interesting artifacts or stalked around piles of old magazines that had begun to disintegrate in backed-up sewage.  The lights in the basement didn’t work and I had to use a flashlight to make my way over the cracked concrete floor, occasionally scaring up the ragged old black cat my dad kept, while holding my shirt over my mouth and nose, afraid of catching some type of disease. Even the garage was piled high with junk, some of which--strange medallions, old coins, car parts--I found truly fascinating. But, in the end, my wariness always won out and I was careful to keep some distance from both my father and his house, sensing, however obliquely, that what was reflected, each in the other, could do me harm. When my father died a few years later there was no clean-up or estate auction. Instead, the city bulldozed his house and everything in it to the ground and carted the wreckage off to the dump. I went by twice afterward; once to see the flattened house and again to see the newly vacant lot. To this day I think that this is really the right and proper way to deal with such homes. Thus, I suppose, I do believe it would be better if jobs such as mine didn’t exist.

The lights in the basement didn’t work and I had to use a flashlight to make my way over the cracked concrete floor, occasionally scaring up the ragged old black cat my dad kept, while holding my shirt over my mouth and nose, afraid of catching some type of disease. Even the garage was piled high with junk, some of which--strange medallions, old coins, car parts--I found truly fascinating. But, in the end, my wariness always won out and I was careful to keep some distance from both my father and his house, sensing, however obliquely, that what was reflected, each in the other, could do me harm. When my father died a few years later there was no clean-up or estate auction. Instead, the city bulldozed his house and everything in it to the ground and carted the wreckage off to the dump. I went by twice afterward; once to see the flattened house and again to see the newly vacant lot. To this day I think that this is really the right and proper way to deal with such homes. Thus, I suppose, I do believe it would be better if jobs such as mine didn’t exist.

Or, I should say, jobs such as mine used to be. I’d like to relate that one day some dramatic realization hit me in some filthy home whose tainted atmosphere suddenly struck me deeply with a dire message. That would be interesting. But, I think, it was more a process of attrition, each “case,” wearing me down a bit more until all I saw was the utter futility and grinding isolation of lives that came to an end surrounded by useless bits of paper and plastic and not much else. We can’t always choose our fate but I’ve seen a lot of what happens when life is simply left to follow its own slow, sad course. Someone had better be at the wheel at all times. What I saw were lives and deaths empty of action or meaning. Finally, I couldn’t stomach the waste. I just had to turn away and find something better to do with my time.

Or, I should say, jobs such as mine used to be. I’d like to relate that one day some dramatic realization hit me in some filthy home whose tainted atmosphere suddenly struck me deeply with a dire message. That would be interesting. But, I think, it was more a process of attrition, each “case,” wearing me down a bit more until all I saw was the utter futility and grinding isolation of lives that came to an end surrounded by useless bits of paper and plastic and not much else. We can’t always choose our fate but I’ve seen a lot of what happens when life is simply left to follow its own slow, sad course. Someone had better be at the wheel at all times. What I saw were lives and deaths empty of action or meaning. Finally, I couldn’t stomach the waste. I just had to turn away and find something better to do with my time.

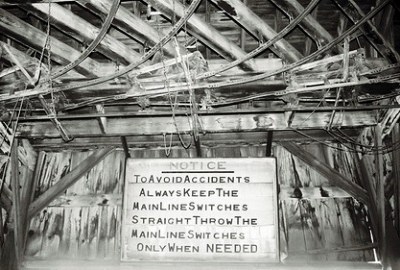

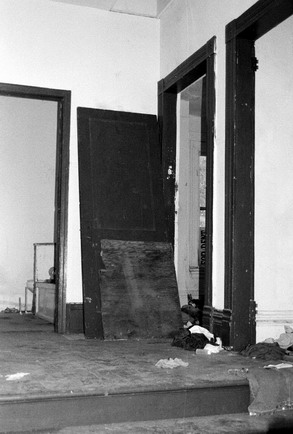

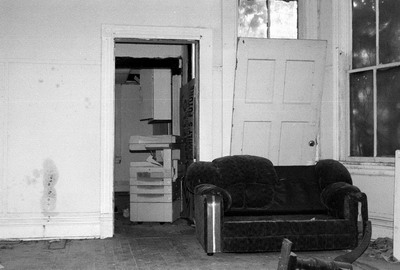

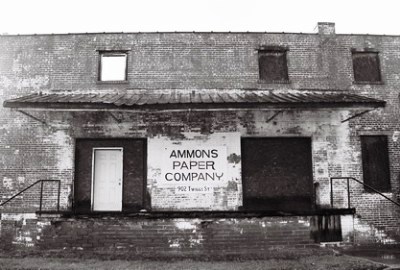

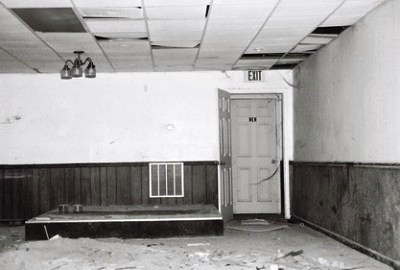

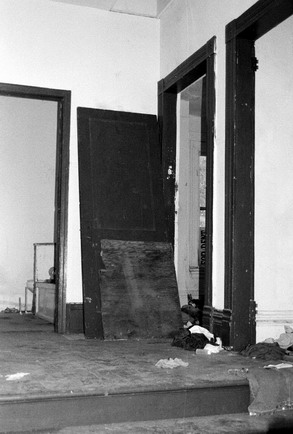

All the above photos were taken Spring 2010 inside three abandoned homes standing right next to each other in downtown Augusta, Georgia, USA.

I first heard of Willis Earl Beal through Found Magazine. Gracing the COVER OF ISSUE #7 was a flier Willis had made in an attempt to meet a “nice pretty girl” and inside was an interview with Willis himself. At the end of the interview was a note telling readers that if they wanted to see some of Willis’s artwork or hear some of his music they should e-mail Found Magazine. I was intrigued by the interview and, as Willis and I lived in the same town, I wanted to see what this guy was up to. So, I e-mailed Found and they told me they hadn’t actually received anything from Willis yet. Could I track him down, collect some of his work, and send it on to them? Well, sure, I could do that. After all, Willis wasn’t hard to reach; his phone number was on the cover of Found Magazine.

While walking home from work one day I gave Willis a call and told him that Found Magazine wanted me to send some of his artwork on to them. He said he had some CD’s with him right then and that we could meet at a nearby Wendy’s, where he was applying for a job. So, I turned around and headed over to the restaurant. I didn’t know if we’d have much to talk about. All I knew about Willis was what I’d read in Found: that he liked nighttime, oatmeal and heavily favored the music of Norah Jones. As it turned out, he also liked Werner Herzog, Bob Dylan and William Burroughs. Alright, then.

I took the CD’s home, not sure what to expect, and put one in the player. The first track I heard was “Blue Escape.”

Once Willis began singing, my first thought was, “I want to be in a band with this guy!” The music came across like a bedroom mix of Sam Cooke, Bob Dylan, the Dirt Bombs and Cat Power. So, I called him back and said I could play some drums, my girlfriend could play guitar, and he could obviously sing and write songs. Did he want to be in a band? Willis was up for trying something, but it took awhile for us to find a place to practice. Our first session was on a cold winter’s afternoon in an open barn, the snow-capped mountains of central New Mexico in the distance. It sounded good. In a short time we had a few tunes worked-out, including some from his home-recorded CD’s. One that Willis never seemed too keen on but that we pretty much insisted on playing was called “Monotony.”

Over the next few weeks we managed to practice once a week or so. We got a set together, booked a show, and got a lead on some recording time. The weekend before the gig we were set to rehearse but Willis didn’t show up on time. This was unusual. An hour later he called saying he was on the way to the airport and was flying back home to Chicago. He and his girlfriend had broken up the night before and he couldn’t stand being in New Mexico another day. He'd told his landlady to just throw all his stuff out. And that was that.

Who knows what might or might not have come of Willis’s songs? But we understood that he had to leave. And many of the songs he was writing seemed to be about his relationship; it would have been hard for him to keep singing them. It’s too bad we didn’t record anything though. My girlfriend and I spent a whole Saturday in thrift stores trying (and failing) to find a simple boom box. Even a practice tape would’ve been nice. Here’s one we eventually worked-up called “White Noize.”

Anyway, Willis is back in Chicago—hopefully writing some new songs—and I figured I’d post a couple of his tunes here on City of Dust. All three of these were from his original home recordings, mostly played on instruments he kept pawning. If anyone wants to hear more songs—and there’s a lot more—get in touch and maybe we can find a way to get them out to folks. Willis can sort of be found on FACEBOOK. But the best way to contact him is still to just give him a call. (UPDATE: Not anymore.)

WOCA medium-format photos are from Albuquerque's West Mesa, the old SANTA FE PENITENTIARY, and the ALBUQUERQUE RAILYARDS, respectively.

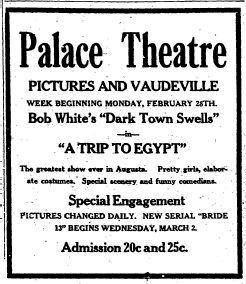

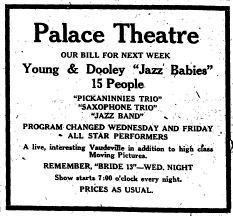

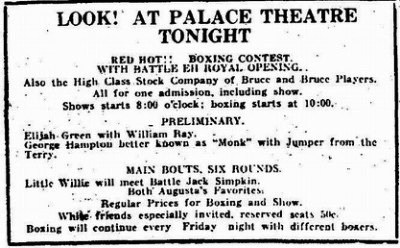

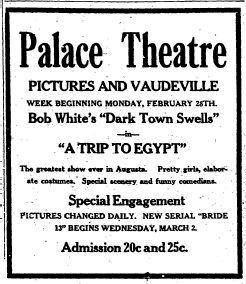

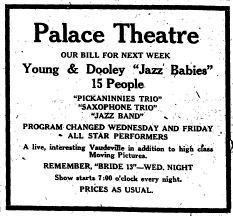

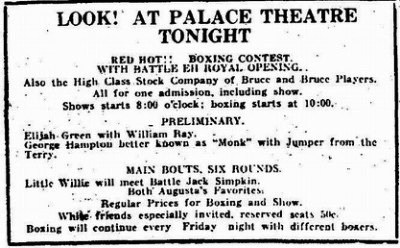

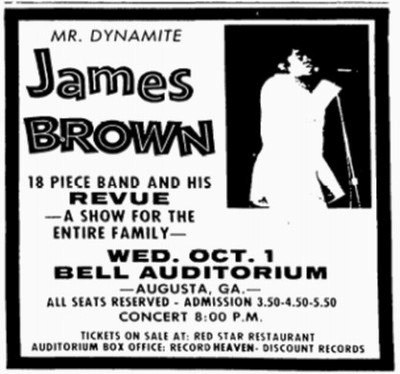

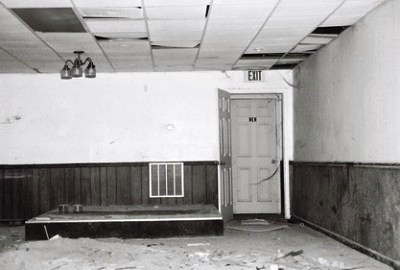

In addition to James Brown’s old neighborhood, my recent trip back to Augusta, Georgia yielded another forgotten treasure: the Palace Theater, later known as the Red Star Restaurant and/or Café. I’d passed this old building countless times on my wanderings up and down deserted James Brown Boulevard, but always assumed it had once been a church or something. And, I guess, in a way, it was.

In addition to James Brown’s old neighborhood, my recent trip back to Augusta, Georgia yielded another forgotten treasure: the Palace Theater, later known as the Red Star Restaurant and/or Café. I’d passed this old building countless times on my wanderings up and down deserted James Brown Boulevard, but always assumed it had once been a church or something. And, I guess, in a way, it was.

The Palace Theater originally opened in 1920 as a vaudeville theater typical of the era except, perhaps, for the fact that it catered to an African-American audience. As such, it is the only theater of its type still standing in Augusta. And, when I say “standing,” that used to imply “just barely.” Recently the entire front façade of the building collapsed into the street. I’m a little surprised that the façade has now been rebuilt exactly as it looked for decades and decades since the place appeared basically abandoned for years. Is something finally going to be done with the old theater? Is its face lift merely because of the new Federal Justice Center across the street? Is the theater still as historic if it has an entirely new façade? I don’t know the answers to any of these questions, I’m just glad they didn’t tear it down.

The Palace Theater originally opened in 1920 as a vaudeville theater typical of the era except, perhaps, for the fact that it catered to an African-American audience. As such, it is the only theater of its type still standing in Augusta. And, when I say “standing,” that used to imply “just barely.” Recently the entire front façade of the building collapsed into the street. I’m a little surprised that the façade has now been rebuilt exactly as it looked for decades and decades since the place appeared basically abandoned for years. Is something finally going to be done with the old theater? Is its face lift merely because of the new Federal Justice Center across the street? Is the theater still as historic if it has an entirely new façade? I don’t know the answers to any of these questions, I’m just glad they didn’t tear it down.

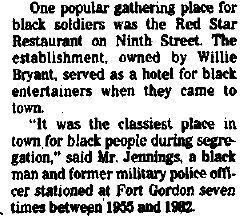

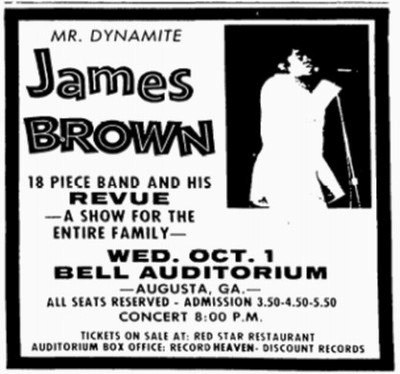

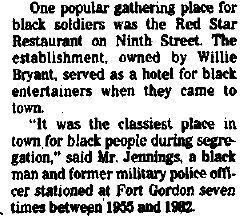

Anyway, the Palace Theater eventually became the Red Star Restaurant. The building may also have housed the Palace Restaurant and the Red Star Café, but I am uncertain as to whether these are real names or just transpositions of the various monikers. The Red Star Restaurant also functioned as a hotel for African-American performers who were in town. Some friends of mine in Augusta referenced an article stating that not only had Ray Charles stayed at the Red Star Restaurant on an early tour, but that he’d played there, as well. Unfortunately, the original article could not be found and, beyond that, there is almost no information to be found on the history of the Palace Theater/Red Star Restaurant, hence the name of this post.

Anyway, the Palace Theater eventually became the Red Star Restaurant. The building may also have housed the Palace Restaurant and the Red Star Café, but I am uncertain as to whether these are real names or just transpositions of the various monikers. The Red Star Restaurant also functioned as a hotel for African-American performers who were in town. Some friends of mine in Augusta referenced an article stating that not only had Ray Charles stayed at the Red Star Restaurant on an early tour, but that he’d played there, as well. Unfortunately, the original article could not be found and, beyond that, there is almost no information to be found on the history of the Palace Theater/Red Star Restaurant, hence the name of this post.

The ONLY PAGE I could find on-line turned out to have some interesting historical information, including a few old ads and posters. As I have only one photo of the building in my archive (had I known its history I certainly would’ve taken more!) I have taken the liberty of presenting these same ads here. I have attempted to contact the owner of this page to no avail but if you happen to read this, Augusta Amusements, thanks for the info and please get in touch. Hopefully you don’t mind my wholesale ranacking of much of your page.

The ONLY PAGE I could find on-line turned out to have some interesting historical information, including a few old ads and posters. As I have only one photo of the building in my archive (had I known its history I certainly would’ve taken more!) I have taken the liberty of presenting these same ads here. I have attempted to contact the owner of this page to no avail but if you happen to read this, Augusta Amusements, thanks for the info and please get in touch. Hopefully you don’t mind my wholesale ranacking of much of your page.

So, I’d like to wrap this post up by asking anyone that has any memories of the Palace Theater/Red Star Restaurant to please submit your recollections via the comment form or e-mail (see my profile for address). I’d love to know who performed, stayed or ate in this building, once a lonely relict amongst lonely relicts on James Brown Boulevard and now a lonely relict across from a massive government complex.

Cleopatra Hill sits at about 5,000 feet above sea level in north-central Arizona. It was here that in 1883 a New York investor, Eugene Murray Jerome, purchased mineral rights from a small group of prospectors and began to finance a mining operation. A short time later, in early 1889, the town of Jerome, encompassing less than one square mile on the side of the steep hill and with a population of eight, was incorporated. The town’s namesake, Mr. Jerome, would never set foot in it.

Jerome really came into its own around the turn of the 20th Century, when the New York Sun dubbed it the “wickedest town in the West.” Of course, this meant that the place was rife with that holy trinity of the Wild West: Gunfights, gambling and working girls.  Nora “Butter” Brown opened the first bordello in Jerome but by the mid-1880’s was already retired and in San Diego. In 1905 she was shot by her husband, an opium addict. Her protégé, Jennie Bauters, didn’t fare much better, leaving Jerome in 1903 only to be shot two years later (the same year as her former boss, incidentally) by her hard-gambling boyfriend in Acme (now Goldroad), Arizona. The boyfriend, Clement C. Leigh, then turned the gun on himself and laid down to die beside Jennie. Only, he didn’t actually die until he was taken behind a stockade and hung for murder. The photo below is of one of the buildings in Jerome where prostitutes lived and worked.

Nora “Butter” Brown opened the first bordello in Jerome but by the mid-1880’s was already retired and in San Diego. In 1905 she was shot by her husband, an opium addict. Her protégé, Jennie Bauters, didn’t fare much better, leaving Jerome in 1903 only to be shot two years later (the same year as her former boss, incidentally) by her hard-gambling boyfriend in Acme (now Goldroad), Arizona. The boyfriend, Clement C. Leigh, then turned the gun on himself and laid down to die beside Jennie. Only, he didn’t actually die until he was taken behind a stockade and hung for murder. The photo below is of one of the buildings in Jerome where prostitutes lived and worked.

The population of Jerome reached 15,000 by the 1920’s with the mines operating 24 hours a day. However, the Great Depression hit the town hard and, in 1930, the mines closed. The history of Jerome during these dark years is lost to the ages. However, in 1935, a man named Phelp Dodge bought up the mining rights around Jerome and began open pit mining, using up to 250,000 pounds of TNT to blow chunks out of the hill, rocking the entire city. One blast sent an entire block sliding downgrade. The vast majority of that block was dismantled, but the jail remains standing to this day. Sort of. Known as the “sliding jail” it now sits tucked away beneath a parking lot, hundreds of feet below its original location. The photo at the top of this post is from inside the jail. The shot below is from just outside.

By the mid-20th Century, nearly 1 billion dollars’ worth of gold, silver, and copper had been hauled out of Cleopatra Hill and the immediate vicinity. But, by then, Jerome had become a true ghost town. Below is a shot of the Connor Hotel, which burned down twice before this brick building was finally built in 1898. Once the classiest hotel in town, by 1931 the place was shuttered. It re-opened in the 1960’s as a flophouse. It shut down again in the 1980’s due to building code violations but has since re-opened as something somewhat above a flophouse.

Today, the population of Jerome hovers around 350, making it the least-populated city in the state of Arizona. Its most famous resident is probably Maynard James Keenan, the singer for Tool, who also co-owns the Caduceus Winery, which has a retail store in town. There’s also a boutique for Keenan’s other band, Puscifer, up a street or two. (Up truly meaning "above" in vertical Jerome.) Even if it’s no longer the “wickedest town in the West” (hello my former home of Oakland, CA!), Jerome still has some ghosts floating around.

The JEROME TIMES has the most extensive history of Jerome to be found on-line. Wanna stay at the Connor Hotel? Go HERE. Thirsty? Try HERE.

Next post is going to be a surprise to everyone, including me.

Back in April of 2005, when City of Dust posts were almost exclusively about the Central Savannah River Area, I wrote something regarding the neighborhood James Brown grew up in, a place once known as “The Terry,” a contraction of “Negro Territory.” I described this area, adjacent to downtown on the west and roughly bounded on the north by Walton Way and Laney Walker Boulevard to the south, as containing Augusta’s poorest and most dangerous streets. I also wrote about how, based on what I’d been told, I had decided not to go exploring those streets, which also meant I did not go looking for the childhood home of James Brown.

Shortly after publishing that post, someone by the name of Tawanda left a comment chastising me for believing what I’d been told. She said that the neighborhood was safe and, while people might be curious to know why I was walking around with a camera, no harm would come to me. Re-reading the original post, ACCESS DENIED, I have to say I'm embarrassed by what I wrote and Tawanda was absolutely right; I’d missed an opportunity to see more of Augusta and, what’s more, visit a neighborhood of great historical interest. I was foolish to be intimidated by what I’d heard. Happily, after a weekend visit to Augusta last week, I can now report that the area around James Brown’s childhood home is not a warzone. Further, to see the lot, and perhaps the actual house, where JB grew up was a real treat. So, without further ado, City of Dust returns to Augusta, Georgia:

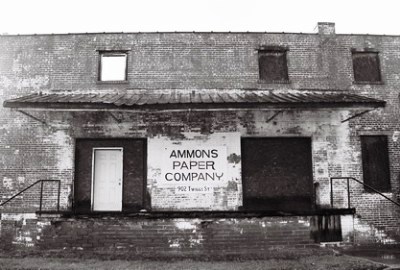

James Brown, Jr. was born in a one-room shack in Barnwell, South Carolina in either 1928 or 1933, although May 3, 1933 seems to be the most accepted date. His parents separated when he was four (some sources say two) and he didn't see his mother again for over two decades. When he was around six, he and his father moved to Augusta and James went to live with his Aunt Honey, who ran a brothel. There, James was reportedly beaten by johns, as well as his father. To pay his way, young James shined shoes and was also sent out to procure customers for his aunt. It is actually unclear from the information I found whether James' father ever lived in the brothel or if he resided elsewhere. In any case, James would have been staying at the address 944 Twiggs St. by the early-to-mid 1930's.

If you do a Google image search for “James Brown’s childhood home” the first photo of a structure you get is one from City of Dust that I can definitely tell you is not the place. However, in 2002, the UK’s Guardian newspaper published a long feature on James Brown by Philip Gourevitch entitled THE TRIP OF A LIFETIME. In it, Mr. Gourevitch is taken on a tour of James Brown’s old stomping grounds by JB himself. They drive around in James’ limo while the Godfather of Soul points out spots of interest, including his boyhood home (that's the lot, at least, in the photo above). I could summarize some of the article, but I think it’ll be more interesting to just plagiarize a few paragraphs:

Here was 944 Twiggs Street, the former brothel where he (i.e., James Brown) lived with his Aunt Honey, the madam - now abandoned and bristling with weeds. Here, by these train tracks, he buck-danced for soldiers passing through town at the start of the second world war; they'd throw him coins, which he took home to Aunt Honey: "Men made 30 cents an hour, 20 cents a hour, 15 cents a hour. I brought her back five dollars to pay the rent for a month." Here was the narrow canal where he once took refuge from the law: "Police were running me, and I saw 'em coming, and I made a few turns, jumped in the water, and breathed through a cane. I saw it in a movie." He mimicked the police, "Where'd he go? Where he at? Where he at? I know I saw him. I swear I saw that boy, Gawd damn." Then he recalled telling himself: "'Now listen up, it's either jail, either reform school, or you stay in the water.' So I stayed in the water." And here was an oil company that he used to rob when he was nine: "That was wrong but was survival."

This is the best available information I’ve ever come across regarding the exact location of the brothel where James Brown grew up. Clearly, the place was not most recently a residence but a business of some kind (see above photo). Was the original home—perhaps a shotgun shack—converted for business use or was it torn down and replaced? Who knows? I do know that the building I photographed pre-dates the article, so, as James didn’t say otherwise, I might assume, with some reservation, that this is where JB grew up. (UPDATE: Twiggs St. was renumbered at some point, and Aunt Honey's brothel would've actually been next door, in a lot to the southwest that was a grassy patch with some trees last time I visited.) The remnants of the railroad tracks can still be seen nearby and, indeed, the canal runs right beside the house. It's fascinating to think that James hid from the police in that same canal all those years ago. Below is a photo of the Southern Milling Company complex, which recently caught fire. This is the view that young James would have seen from the front of his house, although not quite so singed.

Here’s some more from the article:

As we turned off Twiggs Street on to a narrow and particularly abject strip, called Hopkins Street, Mr. Brown's mood turned sombre. The facade of a brick house on the corner was spray-painted with the words "Fuck the world," and farther along the real estate grew more dismal: Tottering clapboard bungalows, half of them burned out, and the rest, he said, "probably crack houses now. You come from that, you use crack." In this setting, the limo looked like a spaceship, but none of the street's ragtag residents expressed any surprise. They waved from sidewalks and porches, and although they couldn't see through the rain-streaked one-way glass, they called out: "Hello, Mr. Brown" and "God bless, Mr. Brown."

The vehicle could belong to nobody else: Every Thanksgiving, he comes through passing out turkeys, and at Christmas he brings toys. Now, he said, "They want me to help build this place back - What can I do? Get on my knees and pray, and ask, 'Mr. President, come - Mr. Bush, come in here and clean it out and put decent homes in here'?"

He told his driver to stop outside a broken-down shack, where an emaciated woman and two young men sat on a porch surrounded by household debris. One of the young men stepped forward in the rain, and Mr. Brown lowered his window and held out a $50 bill. The man bowed and withdrew. "Wait a minute," Mr. Brown called after him. "Y'all split that. Give that lady some, too." When he rolled his window up, he told me: "I'm not doin' this because you here. I wasn't gonna do it today. I didn't want you to see me handin' no money out there. I wasn't gonna do it. That's the honest-to-God truth." He sounded embarrassed. "You look at this, it kinda take your breath," he said.

At the end of the block, we reached JAMES BROWN BOULEVARD, and he said, "Out here on these same streets, you may see my daughter, and she has no business out here. She don't have to be there. I give her a home, she got a new Mercedes, and her Mercedes just sitting there. I can't give it to her, 'cause I can't - 'cause she shrug off everything I do."

Now, the picture painted by the article also makes the neighborhood sound dire. And I certainly saw a number of abandoned homes and businesses, some burnt down. But I never saw a single person that appeared menacing. Granted, the rain was pouring down the afternoon I was there, too, but mostly I saw a place where people were doing their best to get by, some in the face of admittedly long odds. There has also been considerable development along James Brown Blvd since James Brown or I last saw Augusta. The effects of this development on the larger neighborhood remain to be seen, but that a face-lift is occurring is undeniable.

Again, I thank Tawanda for setting me straight and giving me the impetus to find James Brown’s childhood home. If anyone has more information on 944 Twiggs or James Brown’s early residences, please drop me a line. Tawanda, if you happen to read this, please get in touch. I wasn’t able to contact you on this trip, but I may be back in Augusta sometime down the road and would love to take you up on your kind offer of a full tour. Also, many thanks to Mr. Hughes for accompanying me on this outing and providing some historical insight of his own. His website archiving the available information on Henry Shultz and the lost city of HAMBURG SOUTH CAROLINA (site of the HAMBURG RIOT) is well worth spending some time with. The accompanying photo is of the James Brown monument on Broad Street in Augusta. The shot below is another look inside 944 Twiggs St.

Again, I thank Tawanda for setting me straight and giving me the impetus to find James Brown’s childhood home. If anyone has more information on 944 Twiggs or James Brown’s early residences, please drop me a line. Tawanda, if you happen to read this, please get in touch. I wasn’t able to contact you on this trip, but I may be back in Augusta sometime down the road and would love to take you up on your kind offer of a full tour. Also, many thanks to Mr. Hughes for accompanying me on this outing and providing some historical insight of his own. His website archiving the available information on Henry Shultz and the lost city of HAMBURG SOUTH CAROLINA (site of the HAMBURG RIOT) is well worth spending some time with. The accompanying photo is of the James Brown monument on Broad Street in Augusta. The shot below is another look inside 944 Twiggs St.

I think next time we’ll visit the mountainside Wild West gold-mining town of Jerome, Arizona and have a look at its famous, if hidden, “sliding” jail. Jerome is also the home of Maynard Keenan, the singer of Tool. Huh.

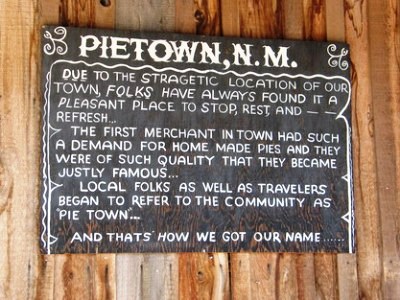

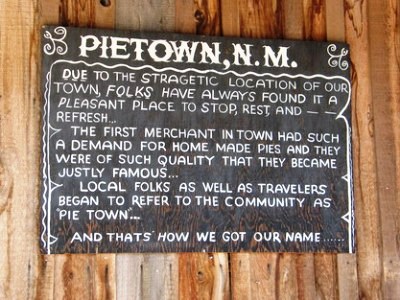

In the pinon-juniper woodland west of Socorro, New Mexico, just east of the Arizona line, is a very small town known for its pie. In fact, it’s been known for its pie ever since a man named Clyde Norman first began baking dried apple pies at a lonely, dusty crossroads atop the Continental Divide back in the 1920’s. Those pies became so famous that, in 1927, the little burg that sprang up around the crossroads became officially known as Pie Town, New Mexico. This despite the wishes of government authorities who thought the name a bit too unconventional.

Initially, US Highway 60, the “Coast-to-Coast Highway,” was poised to become the major east-west route through the southwestern United States. Expectations for the future of Pie Town, which sits at a lofty 7,772’ above sea level, ran high. But Route 66 was put through Albuquerque, about 160 miles to the northeast, marooning Pie Town and leaving the vast region which surrounds it relatively un-traveled. Nevertheless, Pie Town, which remains unincorporated, persisted.

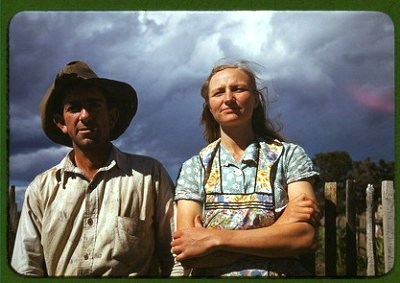

Pie Town really became a town during the Dust Bowl of the 1930’s, when farmers left barren land to the east and attempted to re-start their lives in the rolling hills around Pie Town. At its peak there were perhaps 250 families living in Pie Town and working together, acting as more of a co-operative than a town, everyone banding together to make a living off a land that threatened to be difficult in the best of times. And, as is true in many places and lives, it was often not the best of times. One resident, Faro Caudill, who became sick while living in Pie Town and later decided to add adultery to his list of problems, scrawled a farewell on the gate of his house as he left in 1942: “Farewell, old homestead. I bid you adieu. I may go to hell but I’ll never come back to you.”

But his ex-wife, Doris, whose memories of her time in Pie Town must have been mixed at best, years later recalled the place, and particularly bath time, with some fondness: “We would take a bath on Saturday night. We had a number three bathtub. I’d get the water all hot and then I’d bathe Josie and then I’d take a bath and then Faro would take a bath. . . . You kind of wore the water out.” A rustic lifestyle, to be sure.

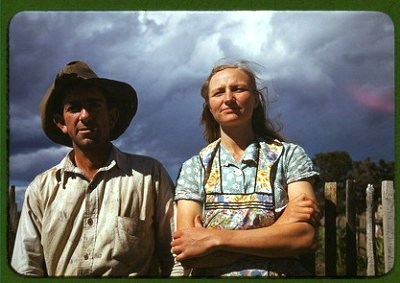

Pie Town, including Faro and Doris Caudill and their daughter, Josie, was well-documented by Russell Lee, who shot 620 photographs in the area for the Farm Security Administration in 1940. These photos, both color and black and white, depict a rural community still reeling from the effects of the Great Depression. Yet there appears to be contentment and community despite the poverty. But things got even tougher in the 1950’s when the climate of the area began to shift, becoming even drier, and the farming went from pretty good, even if sometimes challenging, to impossible. Many of Pie Town’s residents were forced to pack up and head elsewhere. But the pies remained. Below is a photo taken by Russell Lee in October 1940 and entitled "Faro and Doris Caudill, homesteaders, Pie Town, New Mexico."

Pie Town as seen from Highway 60 is perhaps a mile or two long. On the northern side of the highway is the Pie-O-Neer. Just slightly to the west, on the southern side of the road, is the Daily Pie Café. On our stop in Pie Town, we went to the place we came to first: the Pie-O-Neer. The blueberry pie was excellent, as one would expect, and, naturally, there was a countless variety of pies to choose from. But they sell out quick and I was a little disappointed the pecan-oat was gone by the time we arrived. What was somewhat unexpected was how good the rest of the food was. The green chile soup was delicious and even a simple sandwich was well above ordinary. Heck, the tea was pretty nice, too. Also unexpected was finding out that the guy at the table next to ours had attended high school in the same building I’d taken swimming lessons at as a kid, just a few minutes from my childhood home back in Minnesota. The owners of the Pie-O-Neer told us these sorts of encounters happened there all the time. A result, they suspected, of getting people off the interstate and moving at a speed more conducive to engaging with your fellow travelers. Such a shift in priorities is one of their stated goals.

So, why would a person stay in Pie Town, choosing to live in what would appear to be relative isolation? In 2005, Mike Rawl, husband of the Daily Pie Café’s pie chef, told Smithsonian Magazine: “I’ve thought about it a lot. I think the very same impulses that brought the homesteaders out here brought us out. My family, they had the Dust Bowl. Here you’ve got to come out and buy a tax license and deal with insurance and government regulations. But it’s the same thing. It’s about freedom, the freedom to leave one place and try to make it in another. For them their farms got buried in sand. They had to leave. Back in Maryland it never really seemed like it was for us. And I don’t mean for us, exactly. You’re helping people out. This place becomes part of the town. I’ve had people running out of gas in the middle of the night. I’ve got a tank out back here. You’re a part of something. That’s what I mean to say. It’s very hard. You have to fight it. But the life here is worth the fight.”

So, that’s it, really. Freedom and community. And pie. Lots of delicious pie. I’ll be going back soon.

Pie Town’s annual Pie Festival occurs the second Saturday of September. Also of interest is the nearby DanCyn' Windmill Museum, the only windmill museum I believe I've ever seen.

All pictures taken in Pie Town, NM. The most interesting source of information was the article on Pie Town that appeared in Smithsonian Magazine in February 2005. It can be found on-line HERE. Also of interest is a Pie-O-Neer Café page. It's well worth having a look at Russell Lee's photos of Pie Town, which can be found by searching the LIBRARY OF CONGRESS collection. If you do a little searching you might come across the marriage certificate of Faro and Doris Caudill, photographed on the wall of their home prior to Mr. Caudill's indiscretions. Finally, there is an entire book about the Caudills, particularly Doris, titled, "Pie Town Woman," by Joan Myers, a New Mexico author.

(Note to the folks at the Pie-O-Neer: Sorry we forgot the travel info at our table. We really did appreciate it. We just got wrapped up talking to our neighbor from Minnesota and didn’t realize it’d been left behind until Arizona!)

I’ve known Frank Turner for a long time now. Long enough, at least, to get to know some of his ways and habits. For example, I know that Frank wakes up every morning at 4AM and spends the next two hours sitting at his kitchen table with a cup of coffee. Not reading the paper, not watching TV, not doing anything at all. Just sitting there, his elbows on his knees, staring into his cup, a naked bulb in a lamp in the living room casting a thin light over his hunched figure.

I started going over to Frank’s some mornings when I couldn’t sleep. I’d let myself in through the unlatched screen door and Frank would look up at me for a moment as I walked to the kitchen through the breezeway. He wouldn’t say a word. He’d just stand up, take another mug off the shelf, fill it with hot coffee off the stove, and set it down in front of the chair adjacent to his. Neither of us are much for talking, so we didn’t discuss our lives or pasts or plans. We’d just sit there and drink the coffee, sometimes looking out the window at the hills in the distance, watching the contours appear out of the darkness, waiting for that thin band of gold at the horizon that heralded the coming day. When it was time for my shift to start, I’d tell Frank good-bye, thank him for the coffee, and walk out to my truck.

A couple times, early on, I asked him why he woke up so early just to sit at his kitchen table. He’d tell me, “I take a little time to get fit for the day.” Or, “I just need to think on some things.” So, always the same meaning, even if the explanation was slightly different. I didn’t ask him too often, though, and after a short while I didn’t ask him at all. For Frank’s part, he never asked me anything, not even the first time I showed up on his porch at 4:30AM, bleary-eyed and sweating, even though it was early-February and the wind was whipping across the prairie, the cold stinging my cheeks. He only pulled out a chair at the table, made a vague motion with his hand, and set a cup in front of me.

I went over to his place maybe a month ago, about 5AM, after a bad night, and as soon as I opened the screen door, unlatched like it always was, it was like I could sense something had changed. The light in the living room was on and Frank’s cup of coffee was on the table, but he wasn’t there. I called his name softly, then louder, so as not to surprise him with my being there. But there was no answer. I walked around the house and looked in the rooms, but he wasn’t in any of them. Finally, I went into the kitchen and put my palm against his mug. It was warm. The coffee on the stove was still simmering. I walked out to the garage and saw that his truck wasn’t there. The tracks in the gravel driveway were fresh. Then I went back inside, turned off the stove, closed the windows, locked the doors, and got back in my own truck and drove away.

Since then I’ve been back a few times. The coffee in the mug now has a thick oily sheen on the surface, but, other than that, nothing has changed. I’ll keep going back every now and then, but I don’t expect I’ll find him. He must have finally made up his mind about something, I guess.

The photos were taken in Dunnigan Hills, California, USA in fall 2008 with a plastic WOCA camera and medium-format 120 film. The NEXT post will be on Pietown, New Mexico.

The sun was slowly setting over the Petrified Forest, giant slabs of ancient wood and mountains of white bentonite alternately catching fire and fading into shadow. Driving north on Highway 77, the miles ticked past in streams of rusty barbed wire and broken cars.  Millions of glass shards, jagged jewels marking decades of speeding drunks tossing liquid dreams out car windows, glittered from the shoulder of the road and twinkled in the dry yellow grass. Just south of a set of railroad tracks the highway became Navajo Blvd. before intersecting Bucket of Blood St. We stopped the car in the shadow of several tall green dinosaurs. Across the street in one direction was an abandoned tack shop built in the 1920’s. In another direction stood a boarded up wreck of a building made entirely of polished petrified wood. Holbrook (or T’iisyaakin in Navajo), Arizona was suddenly looking like a damned interesting place to spend the night.

Millions of glass shards, jagged jewels marking decades of speeding drunks tossing liquid dreams out car windows, glittered from the shoulder of the road and twinkled in the dry yellow grass. Just south of a set of railroad tracks the highway became Navajo Blvd. before intersecting Bucket of Blood St. We stopped the car in the shadow of several tall green dinosaurs. Across the street in one direction was an abandoned tack shop built in the 1920’s. In another direction stood a boarded up wreck of a building made entirely of polished petrified wood. Holbrook (or T’iisyaakin in Navajo), Arizona was suddenly looking like a damned interesting place to spend the night.

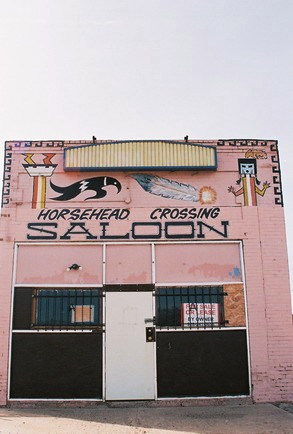

In 1881 (or possibly 1882, there appears to be some dispute), Holbrook, named after the first chief engineer of the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad, was born and immediately became a place to practice the holy trinity of Wild West pursuits: gambling, prostitution and gun fighting. It soon became known as a town “too tough for women or churches.” There was virtually no law in Holbrook and the violence ranged from Apache and Navajo raids on settlers to the Pleasant Valley War, which pitted a family of sheep ranchers against a family of cattle ranchers and lasted ten years, leaving a trail of bodies in its wake.

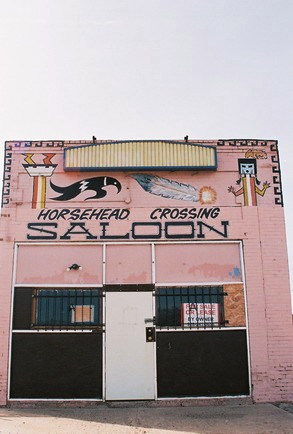

In 1886, the population of Holbrook was about 250 and 26 people died violent deaths, making a citizen's likelihood of being murdered that year something over 1 in 10. Some of the outlaw cowboys in Holbrook were members of the Aztec Cattle Company and worked for the Hashknife Outfit. These cowboys were involved in the Pleasant Valley War, stole cattle, and shot their guns quite a bit. They were known as the “thievinist, fightinist bunch of cowboys in the west."  The main saloon in Holbrook was, of course, the site of much violence, and had the bucolic name Perkins' Cottage Saloon. There are two stories as to why the saloon changed its name that year. The first has some of the boys of the Hashknife Outfit accused of stealing cattle while having a drink. A brutal shoot-out is said to have ensued, leaving numerous patrons dead. The second story, told by Albert F. Potter, captain of the Hashknife's round-up, depicts two Mexican cowboys being shot during a card game by a gambler and a Hashknife Outfit cowboy. The gambler and cowboy quickly rode away on "borrowed" horses. Whichever story is true, it was written that after the incident “buckets of blood” covered the floor of the saloon. Thus the owners decided to change the name of their establishment to better match its disposition. This photo is clearly not of the Bucket of Blood, but it is on the same street.

The main saloon in Holbrook was, of course, the site of much violence, and had the bucolic name Perkins' Cottage Saloon. There are two stories as to why the saloon changed its name that year. The first has some of the boys of the Hashknife Outfit accused of stealing cattle while having a drink. A brutal shoot-out is said to have ensued, leaving numerous patrons dead. The second story, told by Albert F. Potter, captain of the Hashknife's round-up, depicts two Mexican cowboys being shot during a card game by a gambler and a Hashknife Outfit cowboy. The gambler and cowboy quickly rode away on "borrowed" horses. Whichever story is true, it was written that after the incident “buckets of blood” covered the floor of the saloon. Thus the owners decided to change the name of their establishment to better match its disposition. This photo is clearly not of the Bucket of Blood, but it is on the same street.

Over 120 years after its construction, the Bucket of Blood Saloon still stands. You would think that its longevity would ensure that most residents of Holbrook would know its location. Clearly, it’s got to be somewhere on Bucket of Blood St. Yet some locals directed us to the wrong place, telling us that this building made of petrified wood was once the Bucket of Blood Saloon. While a fascinating building in its own right, and probably also a saloon at one time, this was never the Bucket of Blood. The Bucket of Blood is not far away though and I found it somewhat by accident. Not realizing I’d been standing in front of the place until later, the photo below mostly depicts the Bucket of Blood’s neighbor. The Bucket of Blood itself is just to the left, the far-right bit of its lintel just creeping into the frame. I hope to return soon and explore further, now that I’d know what infamy I was looking at.

Clearly, it’s got to be somewhere on Bucket of Blood St. Yet some locals directed us to the wrong place, telling us that this building made of petrified wood was once the Bucket of Blood Saloon. While a fascinating building in its own right, and probably also a saloon at one time, this was never the Bucket of Blood. The Bucket of Blood is not far away though and I found it somewhat by accident. Not realizing I’d been standing in front of the place until later, the photo below mostly depicts the Bucket of Blood’s neighbor. The Bucket of Blood itself is just to the left, the far-right bit of its lintel just creeping into the frame. I hope to return soon and explore further, now that I’d know what infamy I was looking at.

The year after the shoot-out at the Bucket of Blood Saloon, on September 4, 1887, Commodore Perry Owens, the sheriff of Holbrook, dubbed "Saint George with a six-shooter," made it known that law and order had finally come to the territory. While serving a warrant on notorious rustler Andy Cooper at the home of the Blevins Gang, the outlaw tried to close the door on the sheriff. Owens fired through the door with his shotgun, hitting Cooper in the stomach. John Blevins returned fire but shot Cooper's horse instead and was himself shot in the arm. Another man, Mose Roberts, jumped out a window and was killed by Owens. Finally, Samuel Houston Blevins, Cooper's 15-year-old brother, came out the door and ran at the sheriff pointing his dying brother's pistol. Owens shot and the boy died in his mother's arms. In less than a minute the gunfight was over and the back of Holbrook's cattle rustlers had been broken. Owens, now a legend, remained sheriff until 1896, nearly another ten years. The Blevins House still stands.

In 1895, Navajo County was created by the territorial legislature and Holbrook was designated the county seat. The county courthouse was built in 1898 and used as such for 78 years. There were many trials but only one man, George Smiley, convicted of murder, was ever executed. His hanging became notorious for an unusual reason. In the late 1800’s, Arizona law required that every sheriff in Arizona, as well as certain public officials, received an invitation to each execution scheduled to occur in the state. Commodore Perry Owens' successor, Sheriff Frank Wattron, could find no official format or template for such an invitation so he designed his own, complete with flowery language and a gilt-border. It read:

The county courthouse was built in 1898 and used as such for 78 years. There were many trials but only one man, George Smiley, convicted of murder, was ever executed. His hanging became notorious for an unusual reason. In the late 1800’s, Arizona law required that every sheriff in Arizona, as well as certain public officials, received an invitation to each execution scheduled to occur in the state. Commodore Perry Owens' successor, Sheriff Frank Wattron, could find no official format or template for such an invitation so he designed his own, complete with flowery language and a gilt-border. It read:

“You are hereby cordially invited to attend the hanging of one George Smiley, murderer. His soul will be swung into eternity on December 8, 1899, at 3 o’clock p.m., sharp.

Latest improved methods in the art of scientific strangulation will be employed and everything possible will be done to make the surroundings cheerful and the execution a success.

F.J. Wattron, Sheriff of Navajo County.”

It sounded like quite an enjoyable afternoon, but President McKinley believed an execution demanded a certain amount of gravity and, when word of the invitation reached him, he contacted the Governor of Arizona to issue a stay of execution for 30 days and gave Sheriff Wattron a personal reprimand.

So, the sheriff set about writing another invitation. This time it read:

“Revised Statutes of Arizona, Penal Code, Title X, Section 1849, Page 807, makes it obligatory on sheriff to issue invitations to executions, form (unfortunately) not prescribed.

Holbrook, Arizona

Jan. 7, 1900.

With feelings of profound sorrow and regret, I hereby invite you to attend and witness the private, decent and humane execution of a human being; name, George Smiley, crime, murder.

The said George Smiley will be executed on Jan. 8, 1900, at 2 o’clock p.m.

You are expected to deport yourself in a respectful manner, and any ‘flippant’ or ‘unseemly’ language or conduct on your part will not be allowed. Conduct, on anyone’s part, bordering on ribaldry and tending to mar the solemnity of the occasion will not be tolerated.

F.J. Wattron, Sheriff of Navajo County.

I would suggest that a committee, consisting of Governor Murphy, Editors Dunbar, Randolph and Hull, wait on our next legislature and have a form of invitation to executions embodied in our laws."

To ensure the thinly-veiled sarcasm of this second invitation did not result in another letter from President McKinley, Sheriff Wattron sent the invitation out one day before the execution date. George Smiley swung before news of the second invitation ever reached Washington, D.C. and he now haunts the courthouse, perhaps waiting for another message from McKinley, one that will never come. The photo above and the one below are both from the jail in the old Navajo County Courthouse. The night of Wednesday, April 30, 1975 was not a good one in Holbrook.

After reliving the brutality of American history, why not stay in a Wigwam for the night? Wigwam Motel #6 (there were once seven Wigwam Motels throughout the country; three survive) is on Hopi Dr., in central Holbrook. It was built in 1950 and is now on the National Register of Historic Places. Of course, a wigwam is a domed-structure and the “rooms” at the Wigwam Motel are more properly teepees. But why split hairs? There’s a vintage jalopy parked in front of each teepee and when the sun sets it’s not hard to imagine you’re in the real thing.

One last quick fact about Holbrook: On July 19, 1912, a 400 lbs. meteorite exploded over the town. It’s estimated that more than 16,000 stones fell out of the sky, some weighing almost 15 lbs. I guess danger takes a variety of forms in Holbrook.

There’s not too much on the web about Holbrook, but the sites I found most useful were one on the BUCKET OF BLOOD SALOON and another on the NAVAJO COUNTY COURTHOUSE. I also got some information from the Northeastern Arizona Daytrip Guide.

If you want to visit Holbrook and stay at the Wigwam Motel, their website is HERE.

The next post shouldn’t take long to get up—not months, at least. It’s going to be on the much less sordid but perhaps more tasty burg of Pietown, New Mexico.

2012 UPDATE: Below is a better picture of the Bucket of Blood Saloon (on the far left). Note the faded word "saloon" on the lintel. That's the entire rest of the block off to the right. Someone (rich) please open these buildings back up!

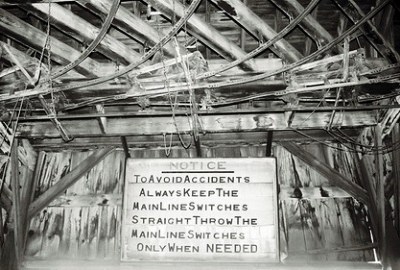

The Albuquerque Rail Yards are a massive complex sprawling over 27.3 acres and sitting (mostly) idle off 2nd St. in the old Barelas neighborhood. Established by the Atlantic and Pacific (A & P) railroad in 1880 after Albuquerque was designated as the division point between the A & P and Santa Fe Railways, the chief function of the complex was to maintain and repair locomotives. However, most of the shops and offices were constructed between 1914 and 1924, by which time the Santa Fe Railway, following bankruptcy in 1883, had re-emerged as the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway, absorbed the A & P, and gained ownership of the yards. By 1919, one-quarter of Albuquerque’s work force was employed at the rail yards and most of the city’s commerce owed its existence to the railroad. At present, there are 14 buildings, mostly clustered in the northern part of the yards; to the south is an operational turntable, built in 1915, which was used to rotate trains as they entered or exited.

(Photo above is facing southeast from the roof of the machine shop toward the turntable. Photo below was taken in the blacksmith shop.)

Of the buildings constructed between 1914 and 1915, only the 35-stall roundhouse and a storehouse stand, while buildings for freight car repairs and a powerhouse have been demolished. However, one of the unique things about the Albuquerque Rail Yards is its state of preservation; virtually every building built from 1916 onward remains, including flue (1920), boiler (1923), blacksmith (1917), and machine (1921) shops, an assembly hall (1922), a firehouse (1920), and a car garage (pre-1931), among others.  The rail yard’s buildings were at the forefront of industrial technology and the 165,000 sq. ft./3.8 acre machine shop has been considered comparable to the 1922 Ford Motor Company Glass Plant, which scholar Grant Hildebrand said was "the single factory which carried industrial architecture forward more than any other." For example, the machine shop’s two-story traveling cranes, one of which could hoist 250 tons, were incorporated into the structure of the building itself. Further, all rail lines, whether inside or outside buildings, ran north-south while a transfer table (pre-1919) for moving locomotives between buildings ran east-west, as did the overhead cranes. Thus the rail yard was sturdy and highly-efficient, with the massive locomotives moved easily from one area to another.

The rail yard’s buildings were at the forefront of industrial technology and the 165,000 sq. ft./3.8 acre machine shop has been considered comparable to the 1922 Ford Motor Company Glass Plant, which scholar Grant Hildebrand said was "the single factory which carried industrial architecture forward more than any other." For example, the machine shop’s two-story traveling cranes, one of which could hoist 250 tons, were incorporated into the structure of the building itself. Further, all rail lines, whether inside or outside buildings, ran north-south while a transfer table (pre-1919) for moving locomotives between buildings ran east-west, as did the overhead cranes. Thus the rail yard was sturdy and highly-efficient, with the massive locomotives moved easily from one area to another.

(Photo above is of the machine shop, taken from the northwest of the building, with cranes at the far end.)

Albuquerque’s early designation as a division point was important because it ensured that the most significant railroad activity in the region would be centered in the city, with the next-nearest division points located in Las Vegas (north), Gallup (west), and San Marcial (south). In the late 1800’s and early 1900’s, a locomotive generally left for a one-way trip of only 100-150 miles in the morning, underwent some basic repairs upon arrival, and then returned later in the day to its home shop for further maintenance. Fire tubes, flues, smoke boxes, and boilers all had to be cleaned daily and ash residue left behind by incompletely burnt coal had to be continually removed.

(Photo above is of the boiler shop as seen from the transfer table, which sits between the boiler and machine shops.)

While early locomotives only managed 40,000 miles between major repair-work, 20th Century engines routinely did 400,000 miles, which put them in the shop for a complete overhaul every year or year-and-a-half. Shops such as those at the Albuquerque Rail Yard completely dismantled locomotives, painstakingly cleaning each part of the engine, lathing wheels, manufacturing replacement equipment, patching and mending and then testing and inspecting the entire engine before sending it back out. A well-cared-for engine might last 15 years and, at its peak, the rail yards tore down and re-built about 40 a month.

(Photo above was taken on the second floor of the machine shop. Note the wooden "bricks," which reduced damage to dropped tools and prevented sparks, which could cause troublesome explosions. Photo below is of the flue shop, aka the "green room".)

Following a steady decline through the Depression, the rail yards experienced a record-high employment of 1500 workers during WWII, when the switch from steam to diesel engines was temporarily halted. Once construction of diesel engines resumed, the rail yards were still used for repairs but, by the mid-1950’s, the massive complex was mostly utilized for maintaining rail lines. The rail yards were largely a storage facility by the time they were completely shut down in the 1990’s. In November 2007, the City of Albuquerque purchased the site with an aim towards restoration. Since that time some TV shows and movies have been shot in the facility, including Crash and Terminator 4, which I’ve heard is responsible for covering the windows in the fake grime which is still visible.

Once construction of diesel engines resumed, the rail yards were still used for repairs but, by the mid-1950’s, the massive complex was mostly utilized for maintaining rail lines. The rail yards were largely a storage facility by the time they were completely shut down in the 1990’s. In November 2007, the City of Albuquerque purchased the site with an aim towards restoration. Since that time some TV shows and movies have been shot in the facility, including Crash and Terminator 4, which I’ve heard is responsible for covering the windows in the fake grime which is still visible.

(Photo above was taken from out on the 250-ton overhead crane in the machine shop.)

One goal of restoration is to create a space for the WHEELS Museum, which would act as a repository for much of the rail yard’s history. Of course, the rail yards are too big for one museum, so some sort of mixed-use residential/commercial area is being envisioned, including restaurants, shops and a concert hall. WHEELS fundraisers are being held and meetings with the city continue. At a Rail Yards Advisory Board Meeting early last year, the President of the future WHEELS Museum said the yards contain some of “most important historic buildings in the state of New Mexico.” Here’s to hoping the process of rehabilitation gets underway quickly, before those holes in the roof get any bigger.

(Photo above is of the boiler shop with overhead crane at the far end.)

Information on the Albuquerque Rail Yard turned out to be pretty hard to find. By far, the best sources were the Wheels Transportation Museum, which has some great content on their WEBSITE, including the best overview of the rail yard’s buildings I could locate.

The other good source was the City of Albuquerque itself, which has some information on the redevelopment plan, including a bit of history.

If you want to get serious about your research, the quote comparing the machine shop to the 1922 Ford Motor Company Glass Plant was from: Grant Hildebrand, Designing for Industry; the Architecture of Albert Ahn, (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1974), pg. 111.

Next post will be on…I have no damn idea, actually.

It was almost 10 years that I worked for the county, up until I couldn’t really take it anymore. For all that time I cleaned-out houses that were going to auction after their owners had died without leaving a living relative or specifying a beneficiary. Sometimes I’d show up pretty much right as the medical examiner was loading the body into the ambulance. Other times it took quite awhile to comb through the deceased’s past and determine if they were, for our purposes, at least, alone in this world. Some people talk about immortality as something to be desired but, from what I’ve seen, outliving (or, perhaps, living long enough to alienate) every one of your friends and family is a fate a far sight worse than death.

It was almost 10 years that I worked for the county, up until I couldn’t really take it anymore. For all that time I cleaned-out houses that were going to auction after their owners had died without leaving a living relative or specifying a beneficiary. Sometimes I’d show up pretty much right as the medical examiner was loading the body into the ambulance. Other times it took quite awhile to comb through the deceased’s past and determine if they were, for our purposes, at least, alone in this world. Some people talk about immortality as something to be desired but, from what I’ve seen, outliving (or, perhaps, living long enough to alienate) every one of your friends and family is a fate a far sight worse than death.  Another time I found a water-stained photo of Marilyn Monroe signed, “To Petey, Love Always, MM.” I’ve tried to compare the writing against other examples I’ve found on the internet and can’t be sure but it might be authentic. Really, though, most of what was in these houses, the vast, vast majority, was of no use to anyone. Old photo albums, paperbacks, clothes, trinkets of every sort and description; things that mattered only to the decedent. Most of this gets put in black plastic bags and taken to the landfill. Even the Goodwill didn’t want it from us. Furniture that is in nice shape, electronic equipment, appliances, and things of some obvious value are shipped to a warehouse and auctioned off four times a year. You might not think that in a city of this size enough people shuffle off this mortal coil entirely without heir to warrant such an operation. In fact, I was part of a twelve-person team and we struggled not to run a backlog.

Another time I found a water-stained photo of Marilyn Monroe signed, “To Petey, Love Always, MM.” I’ve tried to compare the writing against other examples I’ve found on the internet and can’t be sure but it might be authentic. Really, though, most of what was in these houses, the vast, vast majority, was of no use to anyone. Old photo albums, paperbacks, clothes, trinkets of every sort and description; things that mattered only to the decedent. Most of this gets put in black plastic bags and taken to the landfill. Even the Goodwill didn’t want it from us. Furniture that is in nice shape, electronic equipment, appliances, and things of some obvious value are shipped to a warehouse and auctioned off four times a year. You might not think that in a city of this size enough people shuffle off this mortal coil entirely without heir to warrant such an operation. In fact, I was part of a twelve-person team and we struggled not to run a backlog. I think most people expect that death will be a passageway from a life well-lived to something even better. Surrounded by our family and friends there will be anxiety and tears, to be sure, but also the warmth given off by a lifetime of memories and the knowledge that, in a very real way, our life continues in those that come after us. Perhaps it is like that for some. But the evidence I’ve seen would indicate that the end of life can also be a long slide into oblivion, the weight of regret hanging heavy as dreams go unfulfilled or collapse in on themselves entirely. When the mind finally can’t cope I guess madness sets in. I often found it something to consider as I tried to not get involved.

I think most people expect that death will be a passageway from a life well-lived to something even better. Surrounded by our family and friends there will be anxiety and tears, to be sure, but also the warmth given off by a lifetime of memories and the knowledge that, in a very real way, our life continues in those that come after us. Perhaps it is like that for some. But the evidence I’ve seen would indicate that the end of life can also be a long slide into oblivion, the weight of regret hanging heavy as dreams go unfulfilled or collapse in on themselves entirely. When the mind finally can’t cope I guess madness sets in. I often found it something to consider as I tried to not get involved.

The lights in the basement didn’t work and I had to use a flashlight to make my way over the cracked concrete floor, occasionally scaring up the ragged old black cat my dad kept, while holding my shirt over my mouth and nose, afraid of catching some type of disease. Even the garage was piled high with junk, some of which--strange medallions, old coins, car parts--I found truly fascinating. But, in the end, my wariness always won out and I was careful to keep some distance from both my father and his house, sensing, however obliquely, that what was reflected, each in the other, could do me harm. When my father died a few years later there was no clean-up or estate auction. Instead, the city bulldozed his house and everything in it to the ground and carted the wreckage off to the dump. I went by twice afterward; once to see the flattened house and again to see the newly vacant lot. To this day I think that this is really the right and proper way to deal with such homes. Thus, I suppose, I do believe it would be better if jobs such as mine didn’t exist.

The lights in the basement didn’t work and I had to use a flashlight to make my way over the cracked concrete floor, occasionally scaring up the ragged old black cat my dad kept, while holding my shirt over my mouth and nose, afraid of catching some type of disease. Even the garage was piled high with junk, some of which--strange medallions, old coins, car parts--I found truly fascinating. But, in the end, my wariness always won out and I was careful to keep some distance from both my father and his house, sensing, however obliquely, that what was reflected, each in the other, could do me harm. When my father died a few years later there was no clean-up or estate auction. Instead, the city bulldozed his house and everything in it to the ground and carted the wreckage off to the dump. I went by twice afterward; once to see the flattened house and again to see the newly vacant lot. To this day I think that this is really the right and proper way to deal with such homes. Thus, I suppose, I do believe it would be better if jobs such as mine didn’t exist. Or, I should say, jobs such as mine used to be. I’d like to relate that one day some dramatic realization hit me in some filthy home whose tainted atmosphere suddenly struck me deeply with a dire message. That would be interesting. But, I think, it was more a process of attrition, each “case,” wearing me down a bit more until all I saw was the utter futility and grinding isolation of lives that came to an end surrounded by useless bits of paper and plastic and not much else. We can’t always choose our fate but I’ve seen a lot of what happens when life is simply left to follow its own slow, sad course. Someone had better be at the wheel at all times. What I saw were lives and deaths empty of action or meaning. Finally, I couldn’t stomach the waste. I just had to turn away and find something better to do with my time.

Or, I should say, jobs such as mine used to be. I’d like to relate that one day some dramatic realization hit me in some filthy home whose tainted atmosphere suddenly struck me deeply with a dire message. That would be interesting. But, I think, it was more a process of attrition, each “case,” wearing me down a bit more until all I saw was the utter futility and grinding isolation of lives that came to an end surrounded by useless bits of paper and plastic and not much else. We can’t always choose our fate but I’ve seen a lot of what happens when life is simply left to follow its own slow, sad course. Someone had better be at the wheel at all times. What I saw were lives and deaths empty of action or meaning. Finally, I couldn’t stomach the waste. I just had to turn away and find something better to do with my time.

In addition to

In addition to  The Palace Theater originally opened in 1920 as a vaudeville theater typical of the era except, perhaps, for the fact that it catered to an African-American audience. As such, it is the only theater of its type still standing in Augusta. And, when I say “standing,” that used to imply “just barely.” Recently the entire front façade of the building collapsed into the street. I’m a little surprised that the façade has now been rebuilt exactly as it looked for decades and decades since the place appeared basically abandoned for years. Is something finally going to be done with the old theater? Is its face lift merely because of the new Federal Justice Center across the street? Is the theater still as historic if it has an entirely new façade? I don’t know the answers to any of these questions, I’m just glad they didn’t tear it down.

The Palace Theater originally opened in 1920 as a vaudeville theater typical of the era except, perhaps, for the fact that it catered to an African-American audience. As such, it is the only theater of its type still standing in Augusta. And, when I say “standing,” that used to imply “just barely.” Recently the entire front façade of the building collapsed into the street. I’m a little surprised that the façade has now been rebuilt exactly as it looked for decades and decades since the place appeared basically abandoned for years. Is something finally going to be done with the old theater? Is its face lift merely because of the new Federal Justice Center across the street? Is the theater still as historic if it has an entirely new façade? I don’t know the answers to any of these questions, I’m just glad they didn’t tear it down. Anyway, the Palace Theater eventually became the Red Star Restaurant. The building may also have housed the Palace Restaurant and the Red Star Café, but I am uncertain as to whether these are real names or just transpositions of the various monikers. The Red Star Restaurant also functioned as a hotel for African-American performers who were in town. Some friends of mine in Augusta referenced an article stating that not only had Ray Charles stayed at the Red Star Restaurant on an early tour, but that he’d played there, as well. Unfortunately, the original article could not be found and, beyond that, there is almost no information to be found on the history of the Palace Theater/Red Star Restaurant, hence the name of this post.

Anyway, the Palace Theater eventually became the Red Star Restaurant. The building may also have housed the Palace Restaurant and the Red Star Café, but I am uncertain as to whether these are real names or just transpositions of the various monikers. The Red Star Restaurant also functioned as a hotel for African-American performers who were in town. Some friends of mine in Augusta referenced an article stating that not only had Ray Charles stayed at the Red Star Restaurant on an early tour, but that he’d played there, as well. Unfortunately, the original article could not be found and, beyond that, there is almost no information to be found on the history of the Palace Theater/Red Star Restaurant, hence the name of this post. The

The

Nora “Butter” Brown opened the first bordello in Jerome but by the mid-1880’s was already retired and in San Diego. In 1905 she was shot by her husband, an opium addict. Her protégé, Jennie Bauters, didn’t fare much better, leaving Jerome in 1903 only to be shot two years later (the same year as her former boss, incidentally) by her hard-gambling boyfriend in Acme (now Goldroad), Arizona. The boyfriend, Clement C. Leigh, then turned the gun on himself and laid down to die beside Jennie. Only, he didn’t actually die until he was taken behind a stockade and hung for murder. The photo below is of one of the buildings in Jerome where prostitutes lived and worked.

Nora “Butter” Brown opened the first bordello in Jerome but by the mid-1880’s was already retired and in San Diego. In 1905 she was shot by her husband, an opium addict. Her protégé, Jennie Bauters, didn’t fare much better, leaving Jerome in 1903 only to be shot two years later (the same year as her former boss, incidentally) by her hard-gambling boyfriend in Acme (now Goldroad), Arizona. The boyfriend, Clement C. Leigh, then turned the gun on himself and laid down to die beside Jennie. Only, he didn’t actually die until he was taken behind a stockade and hung for murder. The photo below is of one of the buildings in Jerome where prostitutes lived and worked.

Again, I thank Tawanda for setting me straight and giving me the impetus to find James Brown’s childhood home. If anyone has more information on 944 Twiggs or James Brown’s early residences, please drop me a line. Tawanda, if you happen to read this, please get in touch. I wasn’t able to contact you on this trip, but I may be back in Augusta sometime down the road and would love to take you up on your kind offer of a full tour. Also, many thanks to Mr. Hughes for accompanying me on this outing and providing some historical insight of his own. His website archiving the available information on Henry Shultz and the lost city of

Again, I thank Tawanda for setting me straight and giving me the impetus to find James Brown’s childhood home. If anyone has more information on 944 Twiggs or James Brown’s early residences, please drop me a line. Tawanda, if you happen to read this, please get in touch. I wasn’t able to contact you on this trip, but I may be back in Augusta sometime down the road and would love to take you up on your kind offer of a full tour. Also, many thanks to Mr. Hughes for accompanying me on this outing and providing some historical insight of his own. His website archiving the available information on Henry Shultz and the lost city of

Millions of glass shards, jagged jewels marking decades of speeding drunks tossing liquid dreams out car windows, glittered from the shoulder of the road and twinkled in the dry yellow grass. Just south of a set of railroad tracks the highway became Navajo Blvd. before intersecting Bucket of Blood St. We stopped the car in the shadow of several tall green dinosaurs. Across the street in one direction was an abandoned tack shop built in the 1920’s. In another direction stood a boarded up wreck of a building made entirely of polished petrified wood. Holbrook (or T’iisyaakin in Navajo), Arizona was suddenly looking like a damned interesting place to spend the night.

Millions of glass shards, jagged jewels marking decades of speeding drunks tossing liquid dreams out car windows, glittered from the shoulder of the road and twinkled in the dry yellow grass. Just south of a set of railroad tracks the highway became Navajo Blvd. before intersecting Bucket of Blood St. We stopped the car in the shadow of several tall green dinosaurs. Across the street in one direction was an abandoned tack shop built in the 1920’s. In another direction stood a boarded up wreck of a building made entirely of polished petrified wood. Holbrook (or T’iisyaakin in Navajo), Arizona was suddenly looking like a damned interesting place to spend the night.