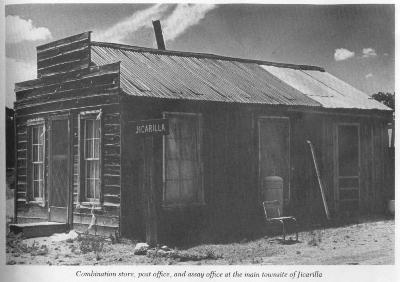

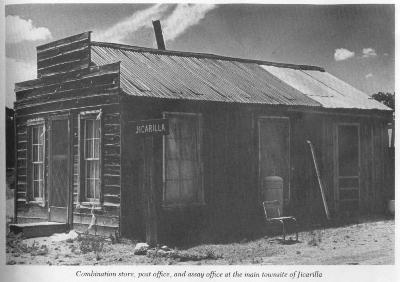

About seven miles south of Ancho, down an unexpectedly bumpy gravel county road (I’ve gotta learn to pay better attention to map symbols), is what remains of Jicarilla. Named for the surrounding Jicarilla Mountains (jicarilla is Spanish for “little basket” or “little gourd”) and, by extension, the Jicarilla Apache, gold first started being pulled out of the area prior to the 1820’s. This is when the Spanish, followed by the Mexicans, came with pans and wooden bowls called “bateas” to work the creeks. Although, truth be told, it was often Native American slaves that did the actual work. In 1864, the U.S. Army forced the local Apache onto distant reservations. By then, Texans had been drifting in and trying their luck for over 20 years. Prospectors arrived en masse in the 1880’s and by 1892 Jicarilla had a post office, which also served as an assay office and store. That's it pictured above. At this time, about 200 people lived in Jicarilla and by 1900 a saloon had opened and the town had a Justice of the Peace.

It was during the Great Depression that the population of Jicarilla peaked at around 300, when desperate people tried to support themselves by gold mining. Actually, I think that kind of thing is happening around the country again right now. Mining could bring in as much as $7 per day and there was plenty of game to provide extra food. But Jicarilla must’ve been a little too remote for most folks as nearly everyone left once the economy improved. By 1942, Jicarilla was pretty much done.

However, some mining continued until relatively recently, when the Lincoln National Forest, which borders Jicarilla, decided to crack down on miners who lived or worked on federal land.

About seven miles south of Ancho, down an unexpectedly bumpy gravel county road (I’ve gotta learn to pay better attention to map symbols), is what remains of Jicarilla. Named for the surrounding Jicarilla Mountains (jicarilla is Spanish for “little basket” or “little gourd”) and, by extension, the Jicarilla Apache, gold first started being pulled out of the area prior to the 1820’s. This is when the Spanish, followed by the Mexicans, came with pans and wooden bowls called “bateas” to work the creeks. Although, truth be told, it was often Native American slaves that did the actual work. In 1864, the U.S. Army forced the local Apache onto distant reservations. By then, Texans had been drifting in and trying their luck for over 20 years. Prospectors arrived en masse in the 1880’s and by 1892 Jicarilla had a post office, which also served as an assay office and store. That's it pictured above. At this time, about 200 people lived in Jicarilla and by 1900 a saloon had opened and the town had a Justice of the Peace.

It was during the Great Depression that the population of Jicarilla peaked at around 300, when desperate people tried to support themselves by gold mining. Actually, I think that kind of thing is happening around the country again right now. Mining could bring in as much as $7 per day and there was plenty of game to provide extra food. But Jicarilla must’ve been a little too remote for most folks as nearly everyone left once the economy improved. By 1942, Jicarilla was pretty much done.

However, some mining continued until relatively recently, when the Lincoln National Forest, which borders Jicarilla, decided to crack down on miners who lived or worked on federal land.  I’ve been told that this was at least partially a result of miners dumping waste in the forest. Whatever the case, the last miner in the area was a man named Jerry Fennell, who had spent 30 years working his claim, finding a little gold here and there, and living in what had been Jicarilla’s general store until one day he was required to submit an official plan of operation. Unable to pay the reclamation bond, Mr. Fennell and Dusty, his well-named burro, shut everything down in the early 2000’s, the last in a line of miners stretching back to the Jicarilla and Mescalero Apaches, who extracted turquoise from the mountains in the late 1500’s.

I’ve been told that this was at least partially a result of miners dumping waste in the forest. Whatever the case, the last miner in the area was a man named Jerry Fennell, who had spent 30 years working his claim, finding a little gold here and there, and living in what had been Jicarilla’s general store until one day he was required to submit an official plan of operation. Unable to pay the reclamation bond, Mr. Fennell and Dusty, his well-named burro, shut everything down in the early 2000’s, the last in a line of miners stretching back to the Jicarilla and Mescalero Apaches, who extracted turquoise from the mountains in the late 1500’s.

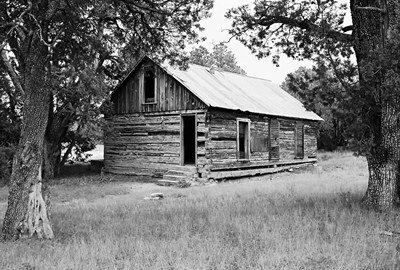

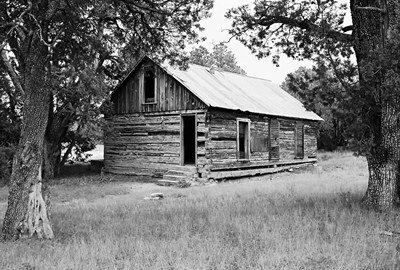

Almost a mile to the south is the log schoolhouse above, built in 1907. Also functioning as a church and general meeting place, it was used through the Depression. The fellow from White Oaks that I mentioned in the LAST POST recalled going to dances in the schoolhouse. He was also at Normandy and told us some harrowing tales of storming the beach. I may say more about him when I finally do a post on White Oaks.

Almost a mile to the south is the log schoolhouse above, built in 1907. Also functioning as a church and general meeting place, it was used through the Depression. The fellow from White Oaks that I mentioned in the LAST POST recalled going to dances in the schoolhouse. He was also at Normandy and told us some harrowing tales of storming the beach. I may say more about him when I finally do a post on White Oaks.

During our visit there appeared to have been some recent activity around a more modern-looking green cabin on the east side of the road. This place is known as the "Hunt Casita," after a family that lived there in the late 1970's. But the post office, small adobe general store (not pictured), and schoolhouse are entirely quiet, as is most of the area around Jicarilla these days. Above is a photo from Philip Varney of the post office looking quite a bit better than it does now, circa maybe 1980.

I got some information for this post from Legends of America. The story of Jicarilla’s last miner (and a good chronology of area mining) can be found HERE. A relative of the Hunt's (and friend of Jerry Fennell) provided a little extra detail. Of course, I grabbed a bit of background and general inspiration from Philip Varney.

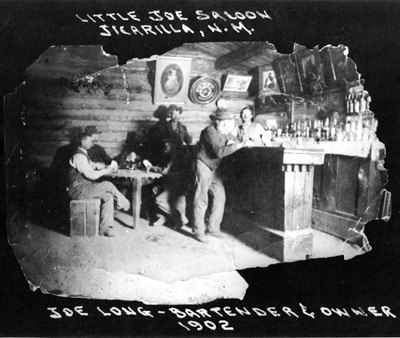

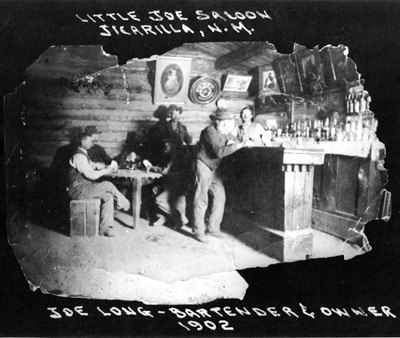

JUNE 2015 UPDATE: I received a photo circa 1902 of the Little Joe Saloon, which is almost surely the same saloon I refer to above as opening in 1900. It is a wonderful shot submitted by the great-grandson and namesake of the saloon's original owner, Joe Long, who lived with his wife Viola in Jicarilla in the early 1900's. Another relative left a comment below about Mr. Long which says that Joe "gave up" the saloon for cattle ranching when his daughter was born in 1908. Apparently Joe and Viola then went on to have 11 more children.

Many thanks to Mr. Long for passing along a fantastic piece of family history which just happens to also be ghost town history.

During our visit there appeared to have been some recent activity around a more modern-looking green cabin on the east side of the road. This place is known as the "Hunt Casita," after a family that lived there in the late 1970's. But the post office, small adobe general store (not pictured), and schoolhouse are entirely quiet, as is most of the area around Jicarilla these days. Above is a photo from Philip Varney of the post office looking quite a bit better than it does now, circa maybe 1980.

I got some information for this post from Legends of America. The story of Jicarilla’s last miner (and a good chronology of area mining) can be found HERE. A relative of the Hunt's (and friend of Jerry Fennell) provided a little extra detail. Of course, I grabbed a bit of background and general inspiration from Philip Varney.

JUNE 2015 UPDATE: I received a photo circa 1902 of the Little Joe Saloon, which is almost surely the same saloon I refer to above as opening in 1900. It is a wonderful shot submitted by the great-grandson and namesake of the saloon's original owner, Joe Long, who lived with his wife Viola in Jicarilla in the early 1900's. Another relative left a comment below about Mr. Long which says that Joe "gave up" the saloon for cattle ranching when his daughter was born in 1908. Apparently Joe and Viola then went on to have 11 more children.

Many thanks to Mr. Long for passing along a fantastic piece of family history which just happens to also be ghost town history.

Lincoln County, New Mexico is Billy the Kid country. The Kid gained his reputation in the Lincoln County War of 1878 and escaped the hangman’s noose by shooting his jailer’s in the Lincoln County Courthouse. I may do an entire post on Billy the Kid and the town of Lincoln someday, but right now we’re going to visit Ancho, in the northwestern part of Lincoln County.

Ancho (pronounced like the first part of “anchovie”) is Spanish for “wide” or “broad” and refers to the valley in which the town sits. Most towns in New Mexico were born by the railroad or minerals and Ancho owes its existence to both. The El Paso and Northeastern Railroad pushed into the valley around 1900 and designated that there be a stop in the vicinity. Within a year, a gypsum deposit was discovered not far away and a plaster mill was built, operated by the Gypsum Product Company. In 1902 (or 1905, depending on your source), a proper railroad depot was put up and some company houses constructed. In 1905, the Ancho Brick Company was created to utilize the abundant fire clay in the area.

Lincoln County, New Mexico is Billy the Kid country. The Kid gained his reputation in the Lincoln County War of 1878 and escaped the hangman’s noose by shooting his jailer’s in the Lincoln County Courthouse. I may do an entire post on Billy the Kid and the town of Lincoln someday, but right now we’re going to visit Ancho, in the northwestern part of Lincoln County.

Ancho (pronounced like the first part of “anchovie”) is Spanish for “wide” or “broad” and refers to the valley in which the town sits. Most towns in New Mexico were born by the railroad or minerals and Ancho owes its existence to both. The El Paso and Northeastern Railroad pushed into the valley around 1900 and designated that there be a stop in the vicinity. Within a year, a gypsum deposit was discovered not far away and a plaster mill was built, operated by the Gypsum Product Company. In 1902 (or 1905, depending on your source), a proper railroad depot was put up and some company houses constructed. In 1905, the Ancho Brick Company was created to utilize the abundant fire clay in the area.

For a time, the heart of Ancho was made of plaster and brick. Ancho-made bricks and plaster helped rebuild San Francisco after the 1906 'quake and more bricks were used for smelter stacks in Arizona. In 1930, the town used its own product to construct a large, brick schoolhouse, replacing the small, wooden, one-room job that burnt down. The school had as many as five teachers and 140 students. However, Ancho was in trouble. Phelps Dodge had purchased the brick plant in 1917, enlarged it, and then shut it down following bankruptcy in 1921. It was finally dismantled in 1937 by the Abilene Salvage Company. There was a slight increase in population during the Depression as desperate families tried to make money mining for gold in the Jicarilla Mountains, but that was short-lived. In 1954, U.S. 54 was laid out, cutting Ancho off by over 2 miles on the route between Corona and Carrizozo. The school closed the following year. In 1959, the railroad shuttered the depot (photos at top and below) and the final nail was put in Ancho’s coffin. Almost.

For a time, the heart of Ancho was made of plaster and brick. Ancho-made bricks and plaster helped rebuild San Francisco after the 1906 'quake and more bricks were used for smelter stacks in Arizona. In 1930, the town used its own product to construct a large, brick schoolhouse, replacing the small, wooden, one-room job that burnt down. The school had as many as five teachers and 140 students. However, Ancho was in trouble. Phelps Dodge had purchased the brick plant in 1917, enlarged it, and then shut it down following bankruptcy in 1921. It was finally dismantled in 1937 by the Abilene Salvage Company. There was a slight increase in population during the Depression as desperate families tried to make money mining for gold in the Jicarilla Mountains, but that was short-lived. In 1954, U.S. 54 was laid out, cutting Ancho off by over 2 miles on the route between Corona and Carrizozo. The school closed the following year. In 1959, the railroad shuttered the depot (photos at top and below) and the final nail was put in Ancho’s coffin. Almost.

In 1963, Mrs. Jackie Silvers purchased the old depot, somehow moved it off the railroad right-of-way, and then filled it with all manner of antiques from the area. My House of Old Things, as the “museum” was called, got a rave review in Varney’s New Mexico ghost town book. He called it “a wonderful conglomeration of all the things you thought nobody had saved” and said it was “not to be overlooked.” But Varney’s book is over 30 years old and so we didn’t get our hopes up. This was good because, while it was still easy to find My House of Old Things, it was immediately clear that it was very closed and had been for years. A disappointing reversal of our fortunes in Chloride. A still-furnished cabin nearby hints at what used to be on display.

In 1963, Mrs. Jackie Silvers purchased the old depot, somehow moved it off the railroad right-of-way, and then filled it with all manner of antiques from the area. My House of Old Things, as the “museum” was called, got a rave review in Varney’s New Mexico ghost town book. He called it “a wonderful conglomeration of all the things you thought nobody had saved” and said it was “not to be overlooked.” But Varney’s book is over 30 years old and so we didn’t get our hopes up. This was good because, while it was still easy to find My House of Old Things, it was immediately clear that it was very closed and had been for years. A disappointing reversal of our fortunes in Chloride. A still-furnished cabin nearby hints at what used to be on display.

Later, in nearby White Oaks, we met a man born in Ancho. It was revealed that Mrs. Sara Jackson, who’d taken over the house when Jackie, her mother, died, passed away several years ago. Her family had expressed no interest whatsoever in maintaining the house or its old things. Apparently many items were sold on EBAY, which we were told was

Later, in nearby White Oaks, we met a man born in Ancho. It was revealed that Mrs. Sara Jackson, who’d taken over the house when Jackie, her mother, died, passed away several years ago. Her family had expressed no interest whatsoever in maintaining the house or its old things. Apparently many items were sold on EBAY, which we were told was “heartbreaking” given their relation to the history of ranching, farming, and homemaking in the region. Who knows what was sold, but peeping inside it appeared that much remains. Furniture, clothes, an old wooden letter box. Through one window was a mannequin head, seemingly presiding over the dust and decay, waiting for something to finally happen. It may be a long wait. The old playground, abandoned over 50 years ago, still stands, made of bolts and bits of pipe that no school would allow children to play on in this day and age. The school, pictured below, seems to have fared better and is now a church. Though who attends I have no idea.

“heartbreaking” given their relation to the history of ranching, farming, and homemaking in the region. Who knows what was sold, but peeping inside it appeared that much remains. Furniture, clothes, an old wooden letter box. Through one window was a mannequin head, seemingly presiding over the dust and decay, waiting for something to finally happen. It may be a long wait. The old playground, abandoned over 50 years ago, still stands, made of bolts and bits of pipe that no school would allow children to play on in this day and age. The school, pictured below, seems to have fared better and is now a church. Though who attends I have no idea.

Not one car passed down the road during our visit. The town was completely silent. Lightning flashed on the horizon and for a brief moment a few big drops of rain fell. Only one building seemed occupied and, indeed, we learned that someone does live there. So, this is Ancho in 2012, population 1.

As so often happens, most of the info for this post came from Philip Varney's ghost town book, but Legends of America fleshed out some details.

Not one car passed down the road during our visit. The town was completely silent. Lightning flashed on the horizon and for a brief moment a few big drops of rain fell. Only one building seemed occupied and, indeed, we learned that someone does live there. So, this is Ancho in 2012, population 1.

As so often happens, most of the info for this post came from Philip Varney's ghost town book, but Legends of America fleshed out some details.

About seven miles south of Ancho, down an unexpectedly bumpy gravel county road (I’ve gotta learn to pay better attention to map symbols), is what remains of Jicarilla. Named for the surrounding Jicarilla Mountains (jicarilla is Spanish for “little basket” or “little gourd”) and, by extension, the Jicarilla Apache, gold first started being pulled out of the area prior to the 1820’s. This is when the Spanish, followed by the Mexicans, came with pans and wooden bowls called “bateas” to work the creeks. Although, truth be told, it was often Native American slaves that did the actual work. In 1864, the U.S. Army forced the local Apache onto distant reservations. By then, Texans had been drifting in and trying their luck for over 20 years. Prospectors arrived en masse in the 1880’s and by 1892 Jicarilla had a post office, which also served as an assay office and store. That's it pictured above. At this time, about 200 people lived in Jicarilla and by 1900 a saloon had opened and the town had a Justice of the Peace.

It was during the Great Depression that the population of Jicarilla peaked at around 300, when desperate people tried to support themselves by gold mining. Actually, I think that kind of thing is happening around the country again right now. Mining could bring in as much as $7 per day and there was plenty of game to provide extra food. But Jicarilla must’ve been a little too remote for most folks as nearly everyone left once the economy improved. By 1942, Jicarilla was pretty much done.

However, some mining continued until relatively recently, when the Lincoln National Forest, which borders Jicarilla, decided to crack down on miners who lived or worked on federal land.

About seven miles south of Ancho, down an unexpectedly bumpy gravel county road (I’ve gotta learn to pay better attention to map symbols), is what remains of Jicarilla. Named for the surrounding Jicarilla Mountains (jicarilla is Spanish for “little basket” or “little gourd”) and, by extension, the Jicarilla Apache, gold first started being pulled out of the area prior to the 1820’s. This is when the Spanish, followed by the Mexicans, came with pans and wooden bowls called “bateas” to work the creeks. Although, truth be told, it was often Native American slaves that did the actual work. In 1864, the U.S. Army forced the local Apache onto distant reservations. By then, Texans had been drifting in and trying their luck for over 20 years. Prospectors arrived en masse in the 1880’s and by 1892 Jicarilla had a post office, which also served as an assay office and store. That's it pictured above. At this time, about 200 people lived in Jicarilla and by 1900 a saloon had opened and the town had a Justice of the Peace.

It was during the Great Depression that the population of Jicarilla peaked at around 300, when desperate people tried to support themselves by gold mining. Actually, I think that kind of thing is happening around the country again right now. Mining could bring in as much as $7 per day and there was plenty of game to provide extra food. But Jicarilla must’ve been a little too remote for most folks as nearly everyone left once the economy improved. By 1942, Jicarilla was pretty much done.

However, some mining continued until relatively recently, when the Lincoln National Forest, which borders Jicarilla, decided to crack down on miners who lived or worked on federal land.  I’ve been told that this was at least partially a result of miners dumping waste in the forest. Whatever the case, the last miner in the area was a man named Jerry Fennell, who had spent 30 years working his claim, finding a little gold here and there, and living in what had been Jicarilla’s general store until one day he was required to submit an official plan of operation. Unable to pay the reclamation bond, Mr. Fennell and Dusty, his well-named burro, shut everything down in the early 2000’s, the last in a line of miners stretching back to the Jicarilla and Mescalero Apaches, who extracted turquoise from the mountains in the late 1500’s.

I’ve been told that this was at least partially a result of miners dumping waste in the forest. Whatever the case, the last miner in the area was a man named Jerry Fennell, who had spent 30 years working his claim, finding a little gold here and there, and living in what had been Jicarilla’s general store until one day he was required to submit an official plan of operation. Unable to pay the reclamation bond, Mr. Fennell and Dusty, his well-named burro, shut everything down in the early 2000’s, the last in a line of miners stretching back to the Jicarilla and Mescalero Apaches, who extracted turquoise from the mountains in the late 1500’s.

Almost a mile to the south is the log schoolhouse above, built in 1907. Also functioning as a church and general meeting place, it was used through the Depression. The fellow from White Oaks that I mentioned in the LAST POST recalled going to dances in the schoolhouse. He was also at Normandy and told us some harrowing tales of storming the beach. I may say more about him when I finally do a post on White Oaks.

Almost a mile to the south is the log schoolhouse above, built in 1907. Also functioning as a church and general meeting place, it was used through the Depression. The fellow from White Oaks that I mentioned in the LAST POST recalled going to dances in the schoolhouse. He was also at Normandy and told us some harrowing tales of storming the beach. I may say more about him when I finally do a post on White Oaks.

During our visit there appeared to have been some recent activity around a more modern-looking green cabin on the east side of the road. This place is known as the "Hunt Casita," after a family that lived there in the late 1970's. But the post office, small adobe general store (not pictured), and schoolhouse are entirely quiet, as is most of the area around Jicarilla these days. Above is a photo from Philip Varney of the post office looking quite a bit better than it does now, circa maybe 1980.

I got some information for this post from Legends of America. The story of Jicarilla’s last miner (and a good chronology of area mining) can be found HERE. A relative of the Hunt's (and friend of Jerry Fennell) provided a little extra detail. Of course, I grabbed a bit of background and general inspiration from Philip Varney.

JUNE 2015 UPDATE: I received a photo circa 1902 of the Little Joe Saloon, which is almost surely the same saloon I refer to above as opening in 1900. It is a wonderful shot submitted by the great-grandson and namesake of the saloon's original owner, Joe Long, who lived with his wife Viola in Jicarilla in the early 1900's. Another relative left a comment below about Mr. Long which says that Joe "gave up" the saloon for cattle ranching when his daughter was born in 1908. Apparently Joe and Viola then went on to have 11 more children.

Many thanks to Mr. Long for passing along a fantastic piece of family history which just happens to also be ghost town history.

During our visit there appeared to have been some recent activity around a more modern-looking green cabin on the east side of the road. This place is known as the "Hunt Casita," after a family that lived there in the late 1970's. But the post office, small adobe general store (not pictured), and schoolhouse are entirely quiet, as is most of the area around Jicarilla these days. Above is a photo from Philip Varney of the post office looking quite a bit better than it does now, circa maybe 1980.

I got some information for this post from Legends of America. The story of Jicarilla’s last miner (and a good chronology of area mining) can be found HERE. A relative of the Hunt's (and friend of Jerry Fennell) provided a little extra detail. Of course, I grabbed a bit of background and general inspiration from Philip Varney.

JUNE 2015 UPDATE: I received a photo circa 1902 of the Little Joe Saloon, which is almost surely the same saloon I refer to above as opening in 1900. It is a wonderful shot submitted by the great-grandson and namesake of the saloon's original owner, Joe Long, who lived with his wife Viola in Jicarilla in the early 1900's. Another relative left a comment below about Mr. Long which says that Joe "gave up" the saloon for cattle ranching when his daughter was born in 1908. Apparently Joe and Viola then went on to have 11 more children.

Many thanks to Mr. Long for passing along a fantastic piece of family history which just happens to also be ghost town history.

Lincoln County, New Mexico is Billy the Kid country. The Kid gained his reputation in the Lincoln County War of 1878 and escaped the hangman’s noose by shooting his jailer’s in the Lincoln County Courthouse. I may do an entire post on Billy the Kid and the town of Lincoln someday, but right now we’re going to visit Ancho, in the northwestern part of Lincoln County.

Ancho (pronounced like the first part of “anchovie”) is Spanish for “wide” or “broad” and refers to the valley in which the town sits. Most towns in New Mexico were born by the railroad or minerals and Ancho owes its existence to both. The El Paso and Northeastern Railroad pushed into the valley around 1900 and designated that there be a stop in the vicinity. Within a year, a gypsum deposit was discovered not far away and a plaster mill was built, operated by the Gypsum Product Company. In 1902 (or 1905, depending on your source), a proper railroad depot was put up and some company houses constructed. In 1905, the Ancho Brick Company was created to utilize the abundant fire clay in the area.

Lincoln County, New Mexico is Billy the Kid country. The Kid gained his reputation in the Lincoln County War of 1878 and escaped the hangman’s noose by shooting his jailer’s in the Lincoln County Courthouse. I may do an entire post on Billy the Kid and the town of Lincoln someday, but right now we’re going to visit Ancho, in the northwestern part of Lincoln County.

Ancho (pronounced like the first part of “anchovie”) is Spanish for “wide” or “broad” and refers to the valley in which the town sits. Most towns in New Mexico were born by the railroad or minerals and Ancho owes its existence to both. The El Paso and Northeastern Railroad pushed into the valley around 1900 and designated that there be a stop in the vicinity. Within a year, a gypsum deposit was discovered not far away and a plaster mill was built, operated by the Gypsum Product Company. In 1902 (or 1905, depending on your source), a proper railroad depot was put up and some company houses constructed. In 1905, the Ancho Brick Company was created to utilize the abundant fire clay in the area.

For a time, the heart of Ancho was made of plaster and brick. Ancho-made bricks and plaster helped rebuild San Francisco after the 1906 'quake and more bricks were used for smelter stacks in Arizona. In 1930, the town used its own product to construct a large, brick schoolhouse, replacing the small, wooden, one-room job that burnt down. The school had as many as five teachers and 140 students. However, Ancho was in trouble.

For a time, the heart of Ancho was made of plaster and brick. Ancho-made bricks and plaster helped rebuild San Francisco after the 1906 'quake and more bricks were used for smelter stacks in Arizona. In 1930, the town used its own product to construct a large, brick schoolhouse, replacing the small, wooden, one-room job that burnt down. The school had as many as five teachers and 140 students. However, Ancho was in trouble.  In 1963, Mrs. Jackie Silvers purchased the old depot, somehow moved it off the railroad right-of-way, and then filled it with all manner of antiques from the area. My House of Old Things, as the “museum” was called, got a rave review in Varney’s

In 1963, Mrs. Jackie Silvers purchased the old depot, somehow moved it off the railroad right-of-way, and then filled it with all manner of antiques from the area. My House of Old Things, as the “museum” was called, got a rave review in Varney’s  Later, in nearby

Later, in nearby  “heartbreaking” given their relation to the history of ranching, farming, and homemaking in the region. Who knows what was sold, but peeping inside it appeared that much remains. Furniture, clothes, an old wooden letter box. Through one window was a mannequin head, seemingly presiding over the dust and decay, waiting for something to finally happen. It may be a long wait. The old playground, abandoned over 50 years ago, still stands, made of bolts and bits of pipe that no school would allow children to play on in this day and age. The school, pictured below, seems to have fared better and is now a church. Though who attends I have no idea.

“heartbreaking” given their relation to the history of ranching, farming, and homemaking in the region. Who knows what was sold, but peeping inside it appeared that much remains. Furniture, clothes, an old wooden letter box. Through one window was a mannequin head, seemingly presiding over the dust and decay, waiting for something to finally happen. It may be a long wait. The old playground, abandoned over 50 years ago, still stands, made of bolts and bits of pipe that no school would allow children to play on in this day and age. The school, pictured below, seems to have fared better and is now a church. Though who attends I have no idea.

Not one car passed down the road during our visit. The town was completely silent. Lightning flashed on the horizon and for a brief moment a few big drops of rain fell. Only one building seemed occupied and, indeed, we learned that someone does live there. So, this is Ancho in 2012, population 1.

As so often happens, most of the info for this post came from

Not one car passed down the road during our visit. The town was completely silent. Lightning flashed on the horizon and for a brief moment a few big drops of rain fell. Only one building seemed occupied and, indeed, we learned that someone does live there. So, this is Ancho in 2012, population 1.

As so often happens, most of the info for this post came from