This month I'd hoped to finally finish a piece on Drawbridge, California, the ghost town in a salt marsh, but time has moved too quickly. So, rather than let City of Dust go dark for all of November, I thought I'd post this tale. While it contains no ghost towns or historical content whatsoever, it does feature the desert as a main character. The photos were taken earlier this month, mostly in Salton City, on the west shore of the Salton Sea, in the Colorado Desert of California. However, the last two shots are from the South Bay Salt Works, the second-oldest continuously operating business in San Diego, CA. See you in December!

THE REAL DESERT

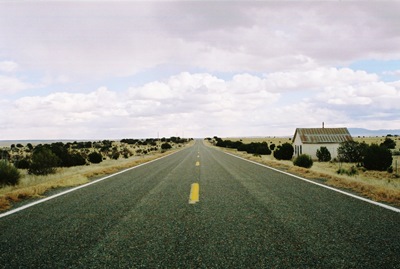

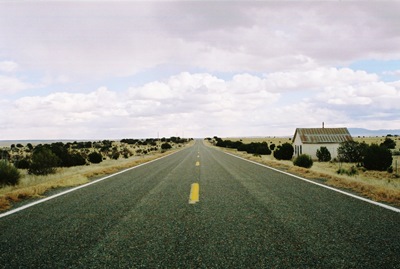

I’m spending a few days out in the desert again. I can’t tell if I’m moving towards something or moving away, but that’s nothing new. Whatever the case, I’ve got some time and a little bit of money so I’ve based myself out of the Whispering Sands Motel, and each morning I set off in a different direction down some desolate, windswept two-laner.

Sometimes it can be hard to find food out here and when I pass a pizza place in what looks like a wooden shack I make a u-turn, park the rental car in about five inches of sand, and go inside. They’ve got some pretty fancy slices for the middle of nowhere and the twenty-something girl behind the counter in Daisy Dukes, tank top, and tattoos seems genuinely thrilled to tell me that the caprese has been drizzled with locally-sourced balsamic vinaigrette and the Greek has real Kalamata olives. This country seems to not actually make things anymore, so I guess we’re going to see if we can float an entire economy on craft beer, pour-over coffee, medical marijuana, tattoos, and artisan pizza. Still, the slices look good and I get one of each. The girl hands them to a large, sweaty guy in the kitchen who pops them in the oven. His tattoos look like they probably cost less than hers and didn’t take nearly as long, either.

There’s no one in the dining room except for five guys in the back who have brought in a couple of their own six packs. They’re discussing “bands that are popular but not super-popular,” and, thankfully, I haven’t heard of most of them. But even so I quickly understand that they have bad taste. I grab a copy of “Sunrunner: The Journal of the Real Desert” off the rack by the door. The subtitle seems a little audacious, but there’s a story about a highway that sounds even more godforsaken than the ones I’ve been traveling. Thus, they get my attention.

The girl brings my slices out on paper plates and starts talking to the guys. At first it seems like maybe they all know each other and she asks them what kind of music they want to hear. I instantly wish she wouldn’t have.

“Do you like Zeppelin?” she says, when, happily, no one suggests anything.

That doesn’t sound terrible to me, but I guess I don’t get a vote.

She flips through her phone for a few more seconds. “How about Glen Campbell?”

Given the surroundings, that sounds better, if stranger. Don’t kids have their own music anymore? This stuff wasn’t even my music.

More silence. “Who?” asks one guy, finally.

“You know, ‘Just like a rhinestone cowboy...,’” sings the girl, only a touch out of tune.

The guys erupt in laughter, one louder than all the others, naturally.

“Nah, nah,” the loud one says, shaking his head and taking a pull off his beer. “I’m good.”

Then another suddenly looks intently at the girl. “Play your favorite song,” he says. “What's your favorite song of all-time?”

The girl is quiet and, after some obvious thought, replies, “That’s hard. That’s maybe something I’d tell somebody after we’d been together for, like, three months.”

The guy raises his hands in front of him, palms up. “What? Don’t we know each other well enough now?”

The girl takes a step backward toward the kitchen just as the guy’s phone rings. He answers, listens for a moment, frowns, then says, “I’m with the bro’s,” and hangs up, much to the amusement of his friends. It’s getting hard to focus on the story about the highway, but it seems to pass mainly through towns named after scientific elements, which is always a good sign.

“No, seriously,” says this guy, starting up again. “Play your all-time favorite song. Let’s get to know each other better.”

“I don’t think so.” The girl takes another step toward the kitchen. “It just seems, like, too personal to me.”

Now the guy lowers his voice. “Come on. I could learn some things about you that are more personal than that. Why don’t you let me? Then maybe you’ll play me your favorite song, too.”

His friends laugh and drink as the girl turns quickly and goes into the kitchen. I can hear the chef talking, but can’t make out the words. I take a few last bites of my balsamic-drizzled caprese, grab my Sunrunner Magazine, and step out the door into a blinding wall of heat and sun.

After a couple dozen miles I decide that I need a palate cleanser and stop at an AM/PM. Spending lots of time in the desert makes me crave salt, so I usually buy Payday bars. But this time I go for a Skor. As I’m reaching down for it a black man comes right up next to me and leans over, too. “Gotcha a little sweet tooth?” he whispers, almost in my ear. This is startling, but the man smiles at me so good-naturedly that as we both straighten up I’m disarmed. He’s wearing a filthy t-shirt and swaying. He seems a little drunk.

“Yeah,” I reply, also whispering, feeling conspiratorial for some reason. “Sometimes I just need a little dessert.”

He grins and blinks his eyes in a funny way before going into his pitch. “Hey, man. You don’t have maybe five dollars I could borrow for gas, do you?” He gestures weakly towards the pumps where he surely has no car. Or truck. Or ATV, for that matter. But I like this guy more than the bro’s, so I give him a dollar, trying to not draw attention from the cashier, who is looking warily in our direction. I tell the man to take care. He tells me to have a nice night and seems to really mean it.

Outside the sun is beginning to set over the spiky mountains, yet it somehow feels hotter. I don’t know how that happens in the desert, but every now and then I notice it. Maybe it’s just my imagination. I’m planning on doing a little off-road exploring the following day, but I didn’t bring any sunscreen and, despite my fondness for blast-furnace landscapes, I really hate suntans. A sunburn seems an affront to myself perpetrated by no one but me, like spitting in my own face. So I drive further into this little town, the softening purple-blue horizon thick with mountains, reminding me why I’m out here in the first place. I begin looking for a drug store.

The first place I come to is Wal-Mart, of course. But they tend to put me in a bad mood. Since I’m pretty much already in a bad mood, I press on. Next, oddly enough, is a K-Mart. Where America shops. The red-headed stepchild to Target’s good son when I was growing up. K-Mart’s seem increasingly rare and I find no reason to ask why as I wander the ravaged shelves under brutal fluorescent lights with a handful of other spaced-out-looking customers. Finally, I find Health and Beauty and choose my protection.

Back outside it’s getting dark and as I head to my car another man sees me across the sand-strewn parking lot, sunscreen swinging in the plastic bag at my side, and begins to walk quickly over. I can feel the heat radiating off the asphalt as I slow down and then come to a full stop. I decide to wait because the man is wearing broken-down cowboy boots with thick, dingy green sweatpants tucked into them. He’s also got on a vest that looks like something a Boy Scout might have made, covered in patches and badges, and cut crudely out of a dark felt material. Underneath the vest he’s bare-chested, his skin the tone and texture of old leather. Finally, he’s sporting a crumpled, sweat-stained, black Stetson, but it’s too large and sits too low, barely above his eyes. As he approaches, he pushes the hat up.

“Hello, sir. Could you spare any change for a burger?”

My curiosity is probably obvious. “Isn’t it a little hot for sweatpants out here?”

The man laughs with seemingly genuine mirth and strikes a pose. “I’m a…a…a…”--he waves a hand theatrically, searching for words--“cock-eyed cowboy.” Crossing his ankles he tilts to one side and then seems to almost curtsey.

I tell him he’s got an interesting look.

“Thank you,” he replies, nodding his head. “Everyone wants to be interesting but nobody wants to pay the price. Me? You can see I paid the price. I may have even paid too much.” He laughs again. “All I can afford now are some ratty-ass sweatpants, a vest I found in a box, and a hat that’s too big for my head.”

I like this guy best of all and give him whatever cash I have left, which turns out to only be $3.72. We wish each other well and go our separate ways into the still desert night, the stars blinking on one-by-one overhead, the waxing yellow moon just clearing the jagged peaks, bathing us both in a gentler kind of light.

But soon enough the warring sun will rise again, and back at the hotel I tell the manager I’ll be checking out the next day. I take my copy of Sunrunner up to my room so I can read more about that highway I’ll be driving in the morning.

Let’s stay in central New Mexico for one more post and add yet another piece to the picture of a region that in the 1920’s was the country’s largest producer of pinto beans. While you probably aren’t going to drive through without reason, as you might Mountainair, nor are you going to find it in most ghost town guides, as you will Claunch, Cedarvale was an important dry land farming and ranching community from the time of its establishment in 1908 until the Dust Bowl and Great Depression combined, along with overgrazing and farm consolidation, to force many of its residents to search for their fortunes elsewhere…yet again.

It was Ed Smith, William Taylor, and Oliver P. DeWolfe who chose the site for Cedarvale and requested that it be surveyed by the U.S. government. The town would be along the route of the New Mexico Central Railroad. Lots were sold through the General Land Office and a post office was soon opened. The new place was named Cedarvale after Cedar Vale, a town in Kansas from which the founders hailed and was also located in a valley with cedars (i.e., junipers).

Soon hundreds of homesteaders from other states arrived on “immigrant trains,” following the lead of Smith, Taylor, and DeWolfe. Most were looking to plant pinto beans. The relatively high altitude (6,384 ft) and short growing season of central New Mexico was good for the beans, which could be dry farmed and were in demand, particularly once World War I began and pinto beans were used to feed soldiers. Come fall, the harvest was stored in Cedarvale’s three elevators.

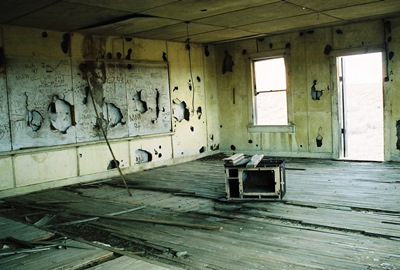

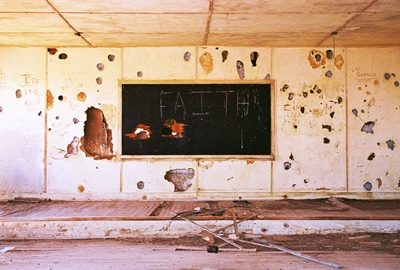

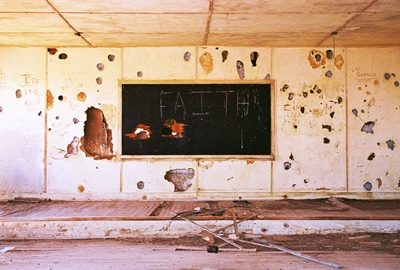

The population of Cedarvale would eventually reach about 500, but is now perhaps half that, and there are no functioning commercial concerns. The post office closed in 1990. But what impresses one most as they approach from the northwest along Highway 42 is the looming wreckage of the Cedarvale School. Initially, the school in Cedarvale was a typical one-room affair, but as both the town and Torrance County grew more space was needed. So, Oliver DeWolfe donated 20 acres of land and, on August 25, 1917, the Torrance County Board of Education approved a bond issuance in the amount of $5,000.00 to construct a new school.

The school was finished in 1921 and an addition made in 1935 via the Works Progress Administration (WPA). By then, the building seems like it would've been surprisingly big for the area, containing four large classrooms, each of which contained three grades and about fifty students. Children attended kindergarten through eighth grade and were then driven in the back of a truck a few miles southeast to Corona for high school. No fancy Bluebird busses here!

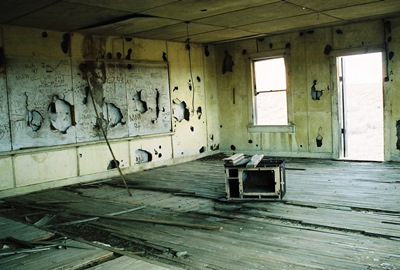

Aside from continuous and dire warnings about rattlesnakes, the massive gymnasium remains perhaps the most striking feature of the Cedarvale School. This was clearly a gathering place for the entire community, as well as a basketball court (complete with raw wooden backboards still in place) and, judging from the design, probably a theater. I’ve heard it hosted some bingo games, too. Despite taking the warnings fairly seriously—signs are even painted on the walls of the school—no rattlesnakes were encountered on this trip.

The school closed in 1953 and is now falling down quickly, the years finally overcoming its sturdy construction. The large wooden beams are impressive, and I’m told the Cedarvale train depot was built to the same hardy specifications. The depot no longer stands, but the materials were re-purposed and used in a home in Albuquerque which is owned by the daughter of a man who helped build both the depot and the school. I’m pleased to have been able to walk around on that historic lumber recently!

There are still many people that have fond memories of growing up in Cedarvale, as is true for virtually all the small central New Mexico towns in which the train once rattled through constantly and the whoosh of pinto beans pouring from the elevator heralded the end of one season and the approach of the next. These are sounds which may yet perhaps be heard, if only faintly, in the startling quiet of places like Cedarvale.

As I said, there ain’t much out there on Cedarvale. David Pike’s “Roadside New Mexico: A Guide to Historic Markers” has a good synopsis of the town’s founding and the history of the school. You can glean a little bit more from “The Place Names of New Mexico” and its similarly-named predecessor, “New Mexico Place Names: A Geographical Dictionary.” Beyond that, you’ll have to hope that maybe someone that was there will tell you what it was like.

Of all the places we could go from long-lost Centerpoint, New Mexico, which we visited last time, perhaps it makes the most sense to simply continue south down Highway 55 and follow it through a few sharp turns until we get to Claunch, something less than 30 miles away. Claunch’s position in central New Mexico put it firmly within the pinto bean empire of the early part of the 20th century, when neighbor Mountainair was proclaiming itself the “Pinto Bean Capital of the World” and soldiers fighting in WWI were eating beans that had been grown in the fertile Estancia Valley.

Back around 1900, when Claunch was being settled, it wasn’t known as Claunch. Instead, it was called Fairview. Or perhaps DuBois Flats, after Frank DuBois, a local cattle and sheep rancher. Or maybe it had been called both. I can find no certainty on the matter. (UPDATE: Claunch was formerly known by both names, with DuBois Flats the earliest, dating to the 1890's.) Whatever the case, Claunch became Claunch near 1930, when the town was big enough to warrant its own post office and a DuBois, NM already existed. Or a Fairview, NM existed. Or both did. But a new moniker was definitely needed and L.H. Claunch, who ran the nearby Claunch Cattle Co., agreed that his surname could be used for the town. Later, he would firmly refuse to let his name be attached to the Claunch Saloon, which thus never opened.

Claunch flourished in the 1910’s and 1920’s, before it was actually called Claunch. However, by the early-1930’s, just as Claunch had gotten its name and post office, the Great Depression and the relentless drought of the Dust Bowl began to hit farmers in the Estancia Valley hard. Within a few years a Works Progress Administration (WPA) school would be built, but as more topsoil was carried off by the howling prairie winds it was already becoming too late. The school closed in the 1950’s, but its skeleton yet sits on the plains.

Where it's been said that there was once a homestead on every 640-acre section in the area, by the late-1960’s it was more like one homestead for every 20 sections, and only six or eight close-knit families inhabited Claunch. These are numbers which have certainly not increased in the last 50 years and the place remains isolated, the nearest towns, as ever, being Mountainair, 37 miles northwest, and Carrizozo, 42 miles southeast.

While Claunch is largely quiet these days, if you listen closely you might hear voices on the breeze, for singing once echoed loudly across the gravel roads. At first, there were gatherings in people’s homes, but then, in 1916, under a brush arbor not far off from town, the Torrance County Singing Convention was born. These were not informal get-togethers, but true events rooted in long religious tradition stretching back to the remote forests of New England in the 1700’s. Ralph Looney, relating his attendance at a convention in Claunch in “Haunted Highways,” even describes learning of shape-notes, a tool intended to aid those who can’t read music, which has a rich history in a unique type of hymn singing in the Deep South often referred to as Sacred Harp.

The Torrance County Singing Convention attracted people from all over the region and even those from other states who had moved away. A yearly state-wide convention could bring in as many as 1200 singers. In DuBois Flats/Fairview/Claunch, the singing convention “year” began on the fourth Sunday in April, with another convention held in June, August, and October. And, as with Sacred Harp “sings” in the South, food--and lots of it--was required to sustain hours upon hours of music in which everyone participated. So, after two hours of singing in the morning, it was time for lunch.

Ralph Looney describes a spread he saw in the mid-1960’s, years after one might’ve assumed Claunch was forgotten: “Meat loaf, fried chicken, roast chicken, ham, beef roast and pork roast. Turkey, molded fruit salads, slaw, tossed salads. Vegetables like pickled beets, green beans, wax beans, mashed potatoes, potato salad, candied yams. Homemade yeast rolls and cornbread. Chocolate cake, angel food, vanilla cake, white cake, apple pie, cherry pie, blueberry pie and so on and on and on and on.” Then would follow at least another three hours of songs such as “Joy is Coming,” “Then We’ll be Happy,” and “When the Roll is Called Up Yonder.”

I’ve been assured there is still fine music being made in Claunch, if not on quite so grand a scale. And the post office is open yet, and operating as a library, too. You can check a book out or swap for one of your own. But as you walk past the old pinto bean elevator, with Ye Olde Dance Hall still faintly visible on the front, and a sign for a museum which it’s probably best you not wait too long to open, it is the past you feel, remarkably soothing--which is not always the case in such places--and somehow alive and singing.

It is perhaps worth adding a short postscript: Claunch lies about 40 miles northeast of the Trinity Site as the crow flies. Given prevailing winds on the morning of the world’s first atomic bomb blast, it was directly in the path of potential fallout. People from the region still talk of cows that turned white after the explosion and were then shown off at local fairs as curiosities to ponder over. But it’s cancer that may be the longest-lasting local legacy of Trinity, and while a group calling themselves the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium has spent years fighting for recognition and compensation, it could be too late for Claunch, whose population is now under 10, the old-timers gone, their families scattered long ago. It's a strange and unsettling footnote in the history of the little town of pinto beans and singing conventions.

Ralph Looney’s “Haunted Highways” provided a wonderful description of Claunch in the 1960’s, while “Ghost Towns Alive” by Linda Harris revisited the town over 40 years later. I grabbed a little info from Robert Julyan’s “The Place Names of New Mexico,” as I tend to do, as well.

Next time we’ll just see where we end up. I’ve got a backlog of locations that only seems to grow larger.

On Highway 55, about 40 miles south of Mountainair, New Mexico, is a charming old one-room schoolhouse. It’s one of those abandoned places that is a sheer pleasure to visit. I even put the above photo on my City of Dust "business" cards. But where exactly are you when you’re at this school? For many years it was a mystery to me as I could find no record of anything besides pinto beans existing in the area. Enter the internet. After a few photos (not even my photos!) of the school showed up on ghost town and history-related Facebook pages, the story of this little dot on the map, which, it turns out, was known as Center Point, finally came to light.

Center Point isn’t in Robert Julyan’s comprehensive The Place Names of New Mexico, but I can still tell you how it got its name: It’s smack dab in the middle of the state, right by Center Point Hill. The only “official” mention of Center Point seems to be in “Mountainair, N.M., Centennial History, 1903-2003” by Bert Herrman (published by Mountainair Public Schools), which includes Center Point in a list of area schools: "Many rural schools were three-month terms and began after New Mexico became a state in January 1912. Teacher's salary was $25 a month. Many of the teachers were 16 or 17 years old; they boarded at homes until small teacherages could be built for them. Dozens of schools dotted the countryside as the region developed. There was Eastview, Center Point, Piñon, Round Top, Ewing, Cedarvale, to name just a few. Typically, each had one room and one teacher that taught grades one through eight. The teachers often lived in shacks next to the schools.”

Beyond that, the initial bit of first-hand information about Center Point came from S. Smith-Cumiford, who saw a photo of the school on-line and said, “That’s on the road to Gran Quivira. It looks like the school built on land donated by my grandfather-in-law, John Cumiford, who was a land-granted rancher and whose homestead ranch was the last to be sold off, in 1985.”

A short time later, H. Thomas added some poignant history about John Cumiford who, it seems, also built the school: “John Cumiford came to Mountainair from Independence, MO in a covered wagon with nine children, his wife dying en route or shortly after as a result of childbirth. He never remarried but was cared for in the late 1950s by my mother-in-law, who had some nursing background. He built this schoolhouse which also doubled as the chapel on Sundays.”

(UPDATE MARCH 2022: It has come to light that John Cumiford did not donate the land for the Center Point School, but for another nearby school that was actually known as the Cumiford School. While some local families maintain that the Center Point School was built on land donated by homesteader Lum Fulfer, references in the Mountainair Independent from 1916-1917 attribute the property to William C. Harrison, as do Mr. Harrison's descendants. The school may also at times have been known as the Harrison School and the Liberty Point School. Whatever name it went by, it was surely constructed by men from the local community, which could've included both Mr. Harrison and Mr. Fulfer, and most likely opened for classes in late 1916 or early 1917. It was closed by 1949, after which time students were bussed to nearby Gran Quivira. However, by then, the area was sparsely populated indeed, and even the school in Gran Quivira closed a short time later, possibly as early as 1950. As a sad aside, Mr. Fulfer was killed in 1935 when a team of mules he was driving bolted and crashed into a gate on his ranch.)

Then came a wonderful account from J.E. Bowers, who spent a couple formative years in Center Point, and through Facebook comments provided what is likely the most extensive history of the place that's been written down: “My mother, Florence Drew Tausworth, taught in that schoolhouse. My brother and I went to school there. We lived in that shack across the street. When it snowed we would wake up with snow on our beds. This was in 1946-1947. There was no community. Just the schoolhouse and the shack. There was a cistern where we got our water. We had a pot-bellied stove in the house. The people lived on their farms and brought their kids to the school.

“My mom taught all the grades. There was a wood stove in the schoolhouse and my brother would go over every morning and light a fire. There were three of us. My oldest brother went to school in Mountainair. It was his job to chop the wood. The wood was brought in by the people that lived in the area. My uncle was the preacher in Mountainair so he would come get us once in a while and take my mom grocery shopping as we had no car.

“I thought it was the most wonderful time in my life, but my brothers felt differently because of the hard work they had to do. Oh yes, I forgot, there was an outhouse. I don't know when the school was abandoned as we moved to Willard the next year. I was quite young. We had enough kids for a baseball team. As you are standing looking at the school, to the back left was where we played baseball. My mom was quite brave to live out there with us three kids.

“The only name I remember that lived close by, maybe a mile or so, was Garrison. One of their sons (Larry, I believe his name was) was a year older than I was. We went back to visit them a year or so later, and Larry had died of food poisoning from home canned green beans.

“The house doesn’t look the same. It has been ‘updated’ since we lived there. LOL. I don't believe it had the ceiling or the drywall and insulation. There were cracks in the walls and ceiling and the wind, snow, or rain would come through. We had to use pots and pans to catch the rain. We had a rain barrel also and we used the water to wash our hair with. Mama would heat water on the stove for us to take baths in the washtub. We had a chamber pot which my brother had to empty every morning. Being the youngest, I never had to do anything.

“We had no toys. So we went wandering. My brother says he got lost one time and it took him quite a while to find his way home. We looked for birds eggs in the piñon trees. We ate a lot of beans. I do remember buying margarine and mixing the yellow packet that came with it. Mother made a lot of corn bread, so cornbread and beans was our main meal with the margarine on the cornbread.

“It's been so long ago that it's taking me a while to think of things. When I said I had no toys, it made me remember. My Aunt Leta Hood cut pictures out of magazines for me. They were my paper dolls. I also had some jacks. I was a whiz at jacks. My mama would get down on the floor and play with me. Years later, when my daughter was that same age and we went to visit my mama, she got down on the floor and played jacks with my daughter.

"My mother was the treasure. I can't imagine taking three children to a place with no modern convenience. This was where I got my love for reading. I read anything and everything. (Even the Montgomery Ward catalog in the outhouse. LOL.) Wouldn't it be nice if things still cost the same as they were in that catalog?

"So many people had it much harder that we did, but fortunately for me and my brothers, we had a very determined mother. So, to me, this story is about my mother, who was determined to be a teacher. She's the one who brought her three children from Texas to New Mexico. And she's the one who probably gave those children in Center Point one of their most memorable school years, as she loved teaching and she loved children.

“Here's what my eldest brother said. (Funny, we all have the exact same memories.): 'Mom taught grades 1 thru 5. I, a 5th grader, was the janitor of the school with a monthly salary of $5.00 which went to mom to help with expenses. During the winter we all slept with a hot rock wrapped in a towel and it went cold too fast. Brother Bob was to keep wood chopped for fire wood and help haul water on wash day. The cistern was always dry and we had to have water hauled in at $10.00 a load. On Christmas eve, the school children put on the Christmas play and we wore bathrobes to be the Three Kings.

"'On New Year's Eve there was a group of local men who played instruments and came and put on a "jam session" for the local people. And, yes, we could have all the pinto beans from the fields we wanted, and go pick leftovers after harvest. But at that altitude they took a long, long time to cook. And I hiked to Gran Quivira one time not realizing it was five miles away. Thought I was never going to get back home. But I found a beauty of an arrow head.

"‘Like you, the only names I can remember are the Garrison's. They lived in the next house north of us, about a mile up the hill, on the east side of the road that was surrounded by trees. There were two boys that I remember, one a senior in high school that year, I believe. I think his name was Glen. He used to supply us with firewood. I don't remember anyone else that I rode with on the school bus. When I was there, probably 20 years ago, I couldn't find the house, and the trees were gone. All that land was bean farming and there were lots of piñon trees. When we were there last, both were gone.’"

It’s true. So much of Center Point has slipped quietly into the past that even its memory was hard to find. But it has been found and now if you Google “Center Point, New Mexico,” well, you might wind up here and read just about everything that’s ever been written down about the place. One thing that has not been found is the house that J.E. Bowers grew up in. If it's still there, it can't be far from the school. I'll have to take a closer look next time I'm in the center of New Mexico. (UPDATE: From J.E. Bowers: "The shack the teachers lived in is gone. It was right across the street. It probably fell down. LOL.")

Information for this post came from people that knew Center Point and that book about schools around Mountainair. And that’s it! I cut-and-pasted the comments of S. Smith-Cumiford, H. Thomas, and J.E. Bowers and her brother from Facebook and with luck they’ll find their way here and give City of Dust their blessing! I thank them for sharing their memories and present them here with the utmost respect, even if I did sort of steal them (for now).

Photos 1-5 were taken in 2009. Photos 6-10 were taken in 2014. Different time of day, different film stock, different time of year.

Next time…I’m not sure. I’ve got more places to write about than time allows, so I’ll just go with what grabs me in a couple weeks. Drawbridge, CA? Claunch, NM? The El Rancho Hotel in Gallup? We shall see.

We’ve spent a lot of time over the past few months in Grant and Sierra Counties, including visits to Hillsboro, Kingston, Fierro, Hanover, and Fort Bayard. So, let's make one more stop in southwestern New Mexico (for now) and check out Lake Valley, site of the famous Bridal Chamber Mine.

Lake Valley lies in the shadow of Monument Peak (aka Lizard Mountain), a prominent knob of rock that nevertheless would’ve given no indication to early travelers of the great wealth waiting nearby. It was 1878 when George W. Lufkin, a Union Army soldier, and his partner Chris Watson went looking for silver not far from Hillsboro. A Chinese man had told Lufkin and Watson in a Georgetown, NM saloon of how he’d ended up lost on the way to Silver City and come across a piece of silver chloride, or horn silver, a very pure, soft form of the mineral, yet could never find where it came from again. That would certainly be a likely story in the Old West. However, both Lufkin and Watson were in their mid-50’s and desperate for a strike. And they thought what they’d heard had the ring of truth. Thus they went out looking for silver. For weeks. With no luck, naturally. Then the story gets contentious, but everyone agrees that somehow Lufkin and Watson stumbled upon silver outcrops. Unfortunately, they’d now been out so long that their initial grubstake was exhausted and they had to quickly head back to Hillsboro to raise more money.

and come across a piece of silver chloride, or horn silver, a very pure, soft form of the mineral, yet could never find where it came from again. That would certainly be a likely story in the Old West. However, both Lufkin and Watson were in their mid-50’s and desperate for a strike. And they thought what they’d heard had the ring of truth. Thus they went out looking for silver. For weeks. With no luck, naturally. Then the story gets contentious, but everyone agrees that somehow Lufkin and Watson stumbled upon silver outcrops. Unfortunately, they’d now been out so long that their initial grubstake was exhausted and they had to quickly head back to Hillsboro to raise more money.

After an additional delay due to Apache depredations, the two miners eventually got back to work, hauling out a half ton of ore and bringing it directly to the Red Onion Saloon in Silver City. Here, John A. Miller saw what had been found and offered the men $1.50 a pound or $1500 for the whole load. Miller went to the assay office, where the geology was better than in the saloon, and quickly learned that the ore ran $12 per pound. So he put up enough money for him, Lufkin, and Watson to mine in earnest.

In the spring of 1881 the men sold their claim to a syndicate led by George Daly. Miller got $100,000 while Lufkin and Watson, along with nine other men, each got $25,000, in addition to the considerable amount they’d already made. Lufkin would build a house nearby in a camp he named after Daly, but the settlement soon moved and became known as Lake Valley in honor of a small lake nearby long since gone dry.

Then, John Leavitt, a blacksmith, leased a claim from the Sierra Grande Mining Company (in which Walt Whitman owned 200 shares!) and spent two days digging in a hole that Lufkin and Watson had started. Lufkin and Watson should’ve gone farther though because at ten feet Leavitt hit a thing that most miners surely didn’t even dare dream of--a cave of solid silver chloride measuring 26 feet wide and 12 feet high. A flame would melt silver right off the ceiling. Despite all this, Leavitt didn’t seem to know what he’d discovered and sold his claim back to the Sierra Grande Mining Company for a few thousand dollars.

(Leavitt's cave, now collapsed, would be in the middle distance in the photo below. The visible mine and rock pile are the result of manganese mining during WWI and II.)

Of a dirty gray color and very malleable, horn silver was soon being cut into large blocks and loaded into railroad cars parked right outside the cave. The ore didn’t even need to be smelted it was so rich. A massive piece, valued at $7,000 (about 394 pounds-worth, silver then being $1.11 an ounce), was exhibited at the Denver Exposition of 1882. In fact, no single concentration of silver has ever exceeded what was quickly named the Bridal Chamber for obvious reasons. All told 2.5 million ounces was exhumed in a couple years, still not even half of the silver taken from the immediate area between 1881 and 1893, when the price of silver collapsed with the end of mandated government purchases. In short, for a few years in the early 1880's, Lake Valley was something else.

It’s often said Lake Valley’s population peaked at 1,000 in 1884, but the 1885 Territorial Census counted only 183 residents. The town moved once and then again to be closer to the Bridal Chamber. One western surveyor tagged Lake Valley as, “…the toughest town I’ve ever seen.” Adding, “I’m satisfied a man died with his boots on every night.” Marshal Jim McIntire was brought into Lake Valley in 1882 to keep the peace at the astounding rate of $300/mo. Those 200 or so folks must have been rowdy indeed. Legendary lawman and strong-arm Jim Courtright was also there and quickly killed two ore thieves in a gunfight. He would kill three more men in Lake Valley.

Yet if Lake Valley was not lacking for silver or bloodshed, it was not lacking in irony, either. George Daly, who had purchased all those area mining claims initially, was killed by Apaches on the day the Bridal Chamber was unearthed by John Leavitt. About the time Leavitt was digging, an area rancher returned home to find his cabin burned and his wife, Sally, as well as one of his children, missing. He immediately rode to Lake Valley to get help. Sally was found, beaten, but safe, and with her child. Still, things were heated between settlers and the Warm Springs raiders led by Nana, Geronimo’s brother-in-law, then in his eighties and still avenging the death of Victorio.

So, that night, a retaliatory ambush was planned. A posse headed to Cotton’s Saloon for some liquid courage and to await the arrival of the Buffalo Soldiers of the Army’s Ninth Cavalry. Lieutenant George Washington Smith was reluctant to join the attack, but he finally relented and his men accompanied the posse. Nana’s camp was found 10 miles west, in Gavilan Canyon, and there, the group charged right into an ambush themselves, with Daly and Lieutenant Smith killed in the initial moments.

As for George Lufkin, who, with Chris Watson, first re-discovered the lost silver near Lake Valley, is also buried in the town’s cemetery; he died without a penny and rests in a pauper’s grave.

In 1908, with Lake Valley having burned in 1895 and already on its way to becoming a ghost town, a man named Oliver Wilson came to make a home. He’d built the Victorio Hotel in Kingston and refused to sell, only to have the bank finally foreclose on him. His daughter, Blanche, was nineteen and as they approached the town saw no way that she could remain in Lake Valley. In the end, she stayed until her death on March 31, 1983, running the Continental Oil distributorship for the area and fully taking the reins after her husband A. Lee Nowlin’s death in 1937. Blanche said her family disapproved of her marriage because Lee was from Texas and “Texans generally weren’t held in very good repute around here in the old days.” Blanche’s next door neighbors in the old Bella Hotel, Pedro and Savina Martinez, were the final holdouts, keeping watch over the town until 1994. Pedro had arrived in Lake Valley in 1904 at the age of two and spent 90 years there.

(Mrs. Nowlin's home is in the photos above and below. Her name can still be made out on the screen door.)

So why would anyone live nearly alone in a ghost town? Blanche Nowlin said, “It’s so peaceful, you know. It’s wonderful to wake up in the middle of the night and hear the silence. This is where all my memories are,” she continued. “There are seven graves over there on that hillside that I can’t leave.” Now she rests amongst them herself.

Much of the background on the cast of characters in Lake Valley came from Haunted Highways by Ralph Looney. Varney’s New Mexico’s Best Ghost Towns and Julyan's The Place Names of NM were also useful, of course. The BLM now operates and oversees Lake Valley and their information also came in handy. I highly recommend a visit soon. Woefully expired "Top Crest" brand 35mm film provided Lake Valley with a violet cast.

Next time we’ll visit a place that even Google won’t tell you about: Centerpoint, NM.

It was the middle of the morning on the Fourth of July and the rain was pounding down. Dirty, gray clouds hung low in the sky. Lightning flashed across the horizon and thunder rumbled ominously. I’d loaded the last of my belongings into the bed of my beat-up Ford Ranger and covered it all with a tarp. I hoped I’d done a good job with the tie-down and that the tarp wouldn’t leak and let the rain damage my cheap, particle-board furniture. Then I thought maybe it didn’t really matter after all.

I was leaving Greenville, South Carolina for Knoxville, Tennessee. I was happy to be getting out of Greenville, but not so sure I really wanted to be going to Knoxville. I’d accepted a nine-month appointment as a research technician in the Department of Chemistry at the University of Tennessee and figured, in the worst case, that it would buy me some more time to plot my next move. I’d just gotten onto Highway 276 outside of town when I saw a man walking up ahead on the shoulder of the road with his thumb out. The rain was relentless and the wipers struggled to keep the windshield clear, especially the passenger side one, which was rotted and squeaked gratingly.

I’d picked up hitchhikers in the past, usually out of boredom or a passing sense of recklessness. Only occasionally had a little bit of compassion entered into it. Every hitchhiker I’d ever given a ride to was at least a little crazy, and usually to the point where you felt you best pay close attention and not let the situation get away from you. But it was always an interesting experience. Once I picked up a guy in Baton Rouge who combined poignant stories of the family he missed badly back in Chattanooga with seamless interjections about a UFO attack he believed was imminent. I thought it took not just a little artistry to pull that off. There was another time someone actually wanted to be taken to a mental institution. He’d managed to wander out of the dayroom and, after a night spent roaming the streets, didn’t know how to get back. He gave me the name of the place and I recognized it. I’d had a cousin that spent some time there. I dropped the man at the front door within 20 minutes. By then the police had been searching for him for hours.

This time I was feeling bored AND reckless. As I passed the man I saw the water running down his face and into his thick beard. No hat. No jacket. That rain was cold. I guess then I felt a little compassion, too. I pulled to the shoulder and flicked on the hazards. The man ran up to the car, swung open the door, and dropped into the seat. He was soaked to the bone. He put a small, very wet, army green duffel bag on the floor. Hitchhikers and their bags. The man’s long, brown hair was plastered to his skull. He was wearing only a blue, flannel shirt, and I could see some tattoos peeking out around his wrists and neck. A lighter shirt would’ve been rendered transparent, providing a better look, but what ink I could see didn’t appear to have been done by a professional. He was also sporting a paunch that hung over his sopping jeans.

“I apologize,” he said, out of breath. “I’m gettin’ your truck all wet.”

“Don’t worry about it,” I replied, pulling back onto the highway. “If this truck gets either of us to where we want to go we can consider ourselves lucky. Speaking of which, where are you going?”

“Knoxville.” Then he began to cough violently and needed a little time to recover. After wiping his mouth with the back of his hand, he continued: “I’d ‘preciate whatever help you can give me in that direction. Only, when you drop me off, could I ask that you leave me at a gas station or someplace dry? I’m gonna die of pneumonia out there.”

The windows of the truck were quickly fogging up. I turned the defroster on full blast. “I’m going to Knoxville myself. I can take you all the way.”

The man seemed to somehow unspool from inside himself. He sank down into the seat with relief. “Brother, you’ll be doing a man that’s down on his luck a solid.” Then he held out his hand. “Name’s Terry, but my homeboys call me T-Dawg. You should, too.”

I shook his hand. It was rough and calloused and ice cold from the rain. “I’m Jack,” I told him. “Where are you coming from?”

T-Dawg didn’t miss a beat. “Prison,” he said. “A seven-year stretch.”

I couldn’t even pretend to be surprised, although I was a little alarmed. “Sorry to hear you were away. How long have you been out?”

He looked at his cheap plastic digital watch, seemingly still functioning despite the deluge. ”’Bout four hours. They transferred me to Greenville last week from Perry for some reason. They just let me out the door this mornin’ and I been walkin’ ever since.”

Now I was even more concerned, but I thought I hid it well. “So, this really is Independence Day for you.”

He paused and then laughed loudly. “Shit! I hadn’t even thought of that! You’re right. Hell yeah it is!”

I wanted to ask why he was in prison, but thought better of it. Instead, I said, “Did you do it?” and instantly regretted the words. I thought it would come off as funny, yet it only struck me as a much worse question.

But T-Dawg laughed even louder. “Man, NO ONE in prison did it. NO ONE!” Then he turned to the side window and wiped away some condensation. “But, yeah,” he added, somberly, “I did it.” As soon as he finished speaking he began to shiver and I switched over to the heater. He rubbed his hands in front of the vent. “Now I just want to see my ex-wife’s old lady and maybe cut the grass at her place, patch the roof, find out where my boy is at.”

Conversations with hitchhikers always seem to swing from jovial, if not entertaining, to dark and disturbing without a moment’s notice. Was T-Dawg really going straight from prison to mow the grass at his ex-wife’s mother’s house? And fix the roof, too? If he didn’t know where his boy was, then he must not have called ahead. I wondered what kind of trouble I was helping instigate. I only nodded.

T-Dawg dug into the top pocket of his shirt and pulled out a soaked pack of Camels. He opened the pack, saw there was no hope, and put it back in his pocket. I thought he’d want to know if I had a cigarette, but instead he asked, “So, how do you make a living?”

“I’m going to do some work for the chemistry department at UT-K. Just a nine-month contract and then who knows? The long-term is uncertain. Story of my life.” I thought the last two sentences might establish some sort of common ground between us. Maybe I was going to need it. But T-Dawg didn’t acknowledge any common ground. Instead, he leaned excitedly across the console. “Chemistry?! That so? Would you have access to maybe a pound of potassium nitrate?” I could’ve sworn he then bit his lip solely to keep from implicating himself further. He chewed at his beard for a few moments, as if deep in thought. “There’s this stump at my ex-wife’s mom’s place that I’d love to blow out of there.”

Again I nodded. “Well, I’d like to help, but I’m working with computers mostly. Data management and stuff. Plus, I haven’t even started yet.”

T-Dawg was clearly disappointed. “Ah, well. Maybe I can ask around a little.” Then he began to cough again.

We continued north through Hendersonville and the rain only seemed to come down harder. “This is going to put a damper on holiday picnics and fireworks,” I offered.

“No shit,” T-Dawg replied. “Do they still do the big display in K-Town? The one where they light the whole damn bridge up?”

I told him I thought that was “Boomsday,” the Labor Day fireworks display in Knoxville, said to be the biggest in the country. But it’d been years since I’d spent any real time in the town and I couldn’t be sure anymore. It seemed impossible to think that they’d be able to have any fireworks at all in weather like this.

T-Dawg stopped shivering and eventually tiny dry patches began to form on his shirt. His hair was drying, too. Walking in that rain must’ve been exhausting, and with a little warmth now T-Dawg fell asleep. His head was against the window, mouth open, and every now and then he made a noise that was something like a groan. I wasn’t about to wake him until it was necessary. As we neared Asheville and I-40 westbound, I felt more relaxed with T-Dawg asleep.

When we approached the outskirts of Knoxville I gave T-Dawg a light tap on the shoulder. I let him take a few moments to remember where--and, perhaps, who--he was, and then asked how to get to where he wanted to go. He told me to exit I-40 at Western Avenue and head northwest. Then, as we came beside the railroad tracks, he indicated a narrow dirt road. We turned right and crossed the tracks into a trailer park that seemed to have been dropped haphazardly into a scraggly pine forest. The rain would’ve kept anyone inside but, judging from the number of satellite dishes, the gravel lanes might’ve been empty of people most of the time anyway. At the end of one street T-Dawg told me to pull onto a worn patch of grass in front of a worn-looking mobile home. I did, but rather than get out, T-Dawg sat there looking at the beaten trailer, saying nothing. Finally, he put his hand on my arm and said, “Come on in. I’d like you to meet someone. Maybe get you a drink, too.”

I searched for an excuse, but with no one waiting for me and nothing much that needed doing, I went blank. Before I could make something up, T-Dawg squeezed my arm and said, “You really oughta come inside.” He looked at me intently, his long, dirty hair and matted beard masking his true expression. Somewhere in this seemed to be the air of a threat.

“Ok,” I said, and opened my door. At least the rain had begun to let up. T-Dawg grabbed his duffel and swung out of the passenger side. As we walked to the trailer, he pointed to the wet grass which, while sparse, did approach my knees in places, making my shoes and jeans damp.

“See this shit?” he said. “I knew it’d still be like this. Always needs mowing. There just ain’t been no one around can do it.” Then he motioned toward the hacked and weathered remains of a pine tree along the side of the trailer. “There’s that fuckin’ stump. If I cain’t blow it out, maybe I can dig some ‘round the roots and chain it to a truck.”

As he ascended the rotten wooden stairs to the warped and peeling door, I dropped back. I couldn’t guess what was about to happen, but I kind of expected it to be bad. T-Dawg knocked and we waited. In a few moments, the door opened slightly and a woman with long, curly, blonde hair peered out while leaving the chain latched. From that brief glimpse I guessed she was in her 50’s, but it was hard to tell. She might’ve been younger. It looked like life could age you fast around this place. All at once her eyes got big and her mouth made a large “O”. The door slammed shut and I immediately felt queasy. I had no idea what I would do if things turned violent. Then I heard the chain rattle and the door swung open. The woman stepped out, threw her arms wide, and yelled, “Oh, my God! Terry!” She was crying. T-Dawg wrapped his arms around her tenderly and I looked away. Not far off a crow was perched in a pine tree, keeping dry in the rain. It was watching us, tilting its head this way and that, quizzically. It wasn’t the only one that was bemused.

It seemed that entire minutes passed before the woman stepped back to take in T-Dawg. Her face was red and damp. She was a little overweight, but now seemed friendly and warm. She was wearing a blue Wal-Mart employee vest. I couldn’t see T-Dawg’s reaction to any of this.

“Why didn’t you tell me?” the woman finally said. “You know I would’ve found a way to get you.”

“I couldn’t trouble ya,” T-Dawg answered. “Ya’ll got enough to do. Anyway, I figured it might best be a surprise.” He stopped and turned to me, still standing below the steps. “My friend Jack gave me a ride. He was heading this way anyhow.”

The woman looked at me as if I’d appeared out of nowhere. “Oh!” she exclaimed, but didn’t go further.

I took a couple steps toward her and extended my hand. “Jack Crawford.”

“Betty Johnson,” she replied, taking my hand very lightly. “Thank you for bringing Terry home. It’s nice to meet you.”

“You, too, ma’am.”

“Well, let’s not stand ‘round gettin’ wet.” T-Dawg motioned us inside as the rain started again. Part of me wanted nothing more than to turn around and get back in my truck but, on the other hand, what was going on between T-Dawg and Betty had gotten my attention.

Inside the trailer were plastic pails and buckets of all sizes and descriptions positioned here and there over the stained and buckled linoleum of the kitchen, scattered across the dingy carpet of the living room, and no doubt trailing off into the bedrooms, and probably the bathroom, too. As the rain strengthened, “plops” seemed to erupt from every direction, a soft, percussive effect without apparent pattern or rhythm at first, but then somehow seeming to cohere. Betty offered me a yellow vinyl chair that was torn, exposing a dirty piece of foam.

“Now, what can I get you after that drive?” she said. “Beer? Iced tea? How ‘bout a sandwich?”

Though I was hungry I couldn’t imagine asking Betty to make me a sandwich, so I just answered, “Iced tea, please.”

Betty dug around in the refrigerator, the back of her blue vest emblazoned with the white words, “How May I Help You?”

T-Dawg asked, “Where’s Tammy?”

Betty began to pour some tea from a big plastic jug. “Memphis, last I heard from her. But that was about six months ago.”

“How’d she sound?”

“About the same as last time you all talked.” Then Betty put the glass in front of me and glanced quickly at T-Dawg. “Maybe a mite worse.”

T-Dawg chewed on his beard and rubbed his hands. Betty asked if he wanted anything, but he shook his head. I took a sip of the iced tea. Plops seemed to be coming from everywhere at once now as the rain pinged harder on the roof. After a few more moments, T-Dawg said, “Can I see Cody?”

Betty was quiet. More rain came down from the sky and more water fell in the buckets. “Of course,” she answered, finally. “I think you need to.”

Then she went off to the back of the trailer and, while T-Dawg and I waited, I heard her talking to someone on the phone. But she spoke quietly and I couldn’t make out the words. I could see T-Dawg straining to pick up the conversation, but then he seemed to give up and leaned toward me. “Hey, could you gimme a lift to one other place? It ain’t far.”

I felt like I had no choice. “Sure. No problem.” I took another drink of tea.

Betty came back out looking serious. “You can go over anytime you want. They’re at home. I’d take you now but I’m afraid I’m already going to be late for work. They don’t accept no excuses at that place.”

T-Dawg made a noise that seemed to be an affirmation and told Betty that I’d drive him. To where, I didn’t know. I finished my tea as T-Dawg grabbed his bag and moved toward the door. He told Betty he’d see her shortly. I stood up and thanked Betty and then we were back outside in the rain, walking quickly to the truck.

We backtracked to I-40 and went south across the roiling, brown Tennessee River on Highway 441. T-Dawg told me to exit on Maryville Pike, but aside from the few directions, he said nothing and only stared out the window at the gloom. Every now and then he coughed a bit more. It sounded like it was getting worse. The wipers swooshed and squeaked. I wasn’t about to say anything.

Finally, T-Dawg told me to slow down and then pointed out a narrow street. I made a left turn and we quickly pulled up beside another trailer. This time the yard was well-manicured with a garden gnome sitting by the front steps and an ornamental wrought iron deer underneath an adjacent pine. It didn’t look like T-Dawg would need to do any work at this place.

I shut off the car and T-Dawg clutched his bag. “Betty’s older sis, Mary, lives here.”

Now at least I knew where we were. It seemed like he wanted to say something more, but he opened the door and got out into the rain. I did likewise. I saw a prim-looking woman’s face through a window and then the door opened before T-Dawg could knock. Mary was thin, dressed in jeans and wearing cowboy boots. Her brown hair was cut short and she looked younger than her sister. She put her arms around T-Dawg, but the reaction was cooler than Betty’s. If she was at all surprised to see him, she didn’t show it.

“This is Jack,” T-Dawg said, pointing to me still standing on the walk, getting wet. I just waved. I felt better closer to the truck.

Mary seemed to be trying to size me up. She was probably wondering why I was there at all. Then she gave a slight shrug, said, “Nice to meet you,” and told us both to come inside.

The trailer was immaculate and warm. A crockpot burbled on a counter in the kitchen and the smell of beef stew was heavy. My stomach rumbled. A framed piece of needlepoint by the door read, “God Bless This Home and All Who Enter,” and some country music played low in the background. “Dixieland Delight” by Alabama.

Mary offered me a seat, then looked at T-Dawg and said, “I’ll go get him.” She went down the hallway and in less than a minute returned with a boy beside her. He was thin and his black t-shirt said “TENNESSEE” across the front in orange block letters. His hair was exactly the color of T-Dawg’s and as unruly. His eyes were wide, although he avoided looking directly at anyone. He couldn’t have been ten years old and he was scared. Mary stopped directly across the kitchen from us and put her arm around the boy’s shoulder.

“Cody, your daddy’s here.” The boy seemed to draw up into himself. “He’s come to see you.”

T-Dawg put his duffel down and took a few slow steps toward Cody. Then he put a hand on his son’s head, tousling his hair gently. “How you been, lil’ man? You taking care of things while I been gone?”

It seemed impossible, but the boy’s eyes got wider. His mouth opened, but instead of speaking he pulled away from Mary’s side and ran back down the hallway.

T-Dawg looked stunned, and then like he might cry. He made a movement toward the hall but Mary stopped him. “Let the boy be. He needs some time. He’s just scared.”

T-Dawg snorted. “Scair’t of his own daddy.”

Suddenly it was like a dark cloud passed over Mary’s face. “The last time he saw you he could barely say ‘daddy’,” she hissed, coldly. “You’re lucky he even remembers you enough to be scared.” T-Dawg put a hand against the wall as if to brace himself. “Why wouldn’t you let him see you all these years, anyway? A boy needs his father, even if his father’s in prison.”

T-Dawg stared at the shiny linoleum floor. He seemed dissipated. “Because I didn’t want him to see me there. I didn’t want him to have memories of his daddy like that.”

“So you thought no memories at all would be better?” T-Dawg just shook his head. “He’s acting out at school, you know. Gets in fights. Won’t do what the teachers ask him. ADHD was what the doctor said. He gave us some medication.”

T-Dawg took a minute to process this. “Does the medication help?”

“It seems to, I think. At least when I can get him to take the pills. Sometimes he hides them under his tongue and spits them out when I’m not looking. Now I make him open his mouth and show me.”

T-Dawg went back to staring at the floor. Mary softened. “But he’s a good kid. He’s got a good heart. You’ll like him. You just need to make sure he likes you.”

T-Dawg truly did start crying. Now I stared at the floor.

“What are your plans, Terry?” asked Mary, after a while.

“Oh, I ain’t going nowhere,” said T-Dawg with a sniffle.

“Good,” Mary replied, then repeated, almost at a whisper: “Good.”

T-Dawg started coughing again and walked through the kitchen and out the door without another word. Mary watched him, then turned and went back down the hall. I didn’t know what else to do, so I followed T-Dawg outside. The rain had eased again. He was sitting on the bottom stair step. The aluminum storm door rattled, but he didn’t seem to hear me. I stopped as he pounded his big fist into his right thigh. Hard. Then he did it again. I waited a few moments before scuffing my foot on the wooden step to get his attention. He turned and looked at me like I was a ghost, then ran his palm quickly across his face. “Hey, man, I want to thank you. You been good to me.” He reached out his hand and I took it. I felt an unexpected surge of emotion. I came down the steps and wasn’t sure what to do. “Have a good Fourth,” I said, and instantly felt like an idiot.

T-Dawg looked confused but then grinned, his stained teeth showing behind his beard. “Yeah, God bless America, man!”

Then I walked to my truck, got in, and pulled away. T-Dawg gave me a wave. I was barely back to Maryville Pike when the rain started falling harder once more. It was beginning to get dark so I decided to make a quick stop at Taco Bell and then head over to see what was going on at World’s Fair Park. I‘d finally remembered that that was where they had the Fourth of July celebration in Knoxville, and I wanted to know if maybe they’d come up with a way to shoot off fireworks even in rain like this.

It's been a long time since I stepped back from ghost towns for a moment and posted a story. February 21, 2014, to be exact, when I put up a piece set in Socorro County, New Mexico, called "The Monsoon." Not only does the story above take place (mostly) in Knoxville, Tennessee, but the photos all came from there, as well. On the perhaps rather off-chance that you want more of this kind of thing, you can always check out the City of Dust collection, A Loss For Words, on Amazon.com.

Next time we're off to the ghost town of Lake Valley, New Mexico, once home of the famous Bridal Chamber Mine.

and come across a piece of silver chloride, or horn silver, a very pure, soft form of the mineral, yet could never find where it came from again. That would certainly be a likely story in the Old West. However, both Lufkin and Watson were in their mid-50’s and desperate for a strike. And they thought what they’d heard had the ring of truth. Thus they went out looking for silver. For weeks. With no luck, naturally. Then the story gets contentious, but everyone agrees that somehow Lufkin and Watson stumbled upon silver outcrops. Unfortunately, they’d now been out so long that their initial grubstake was exhausted and they had to quickly head back to Hillsboro to raise more money.

and come across a piece of silver chloride, or horn silver, a very pure, soft form of the mineral, yet could never find where it came from again. That would certainly be a likely story in the Old West. However, both Lufkin and Watson were in their mid-50’s and desperate for a strike. And they thought what they’d heard had the ring of truth. Thus they went out looking for silver. For weeks. With no luck, naturally. Then the story gets contentious, but everyone agrees that somehow Lufkin and Watson stumbled upon silver outcrops. Unfortunately, they’d now been out so long that their initial grubstake was exhausted and they had to quickly head back to Hillsboro to raise more money.