If you’re tooling around the Rio Puerco Valley northwest of Albuquerque, one feature will loom in the distance, possibly beckoning you to come closer (or even climb it), and that’s Cabezon Peak, a volcanic plug left after the erosion of a larger cinder cone. This feature was known as Wasema'a to the Jemez. To the Isletans it was Tchi'kuienad. The Navajo called it Tsenajin, or Black Peak. For them, it represented the head of a giant that had been killed on Mount Taylor, a sacred place, by the Twin Brothers, or War Gods. The lava at the base of the peak then was the giant's blood.

Tsenajin represented the eastern edge of the Navajo's tribal world until the Spanish began to move west of what they, in turn, called El Cabezón, or "The Big Head." The peak is about 2,000 ft. higher than the surrounding landscape and, in 1849, Lt. James Simpson of the U.S. Army traveled through and wrote about "the remarkable peak called Cerro de la Cabeza." It is still remarkable.

Today, just below Cabezon Peak, on the north bank of the Rio Puerco, are the sun-blasted remains of a small village. This is what’s left of Cabezón, New Mexico, settled, it's said, in 1826 by Juan Maestas, who came from Pagosa Springs, Colorado. It was one of four small Hispano agricultural settlements in the area, along with Guadalupe, San Luis, and Casa Salazar. But even before that, going back to the late 1700s, Hispano farmers here had grown corn and chile and harvested wild asparagus along the Rio Puerco.

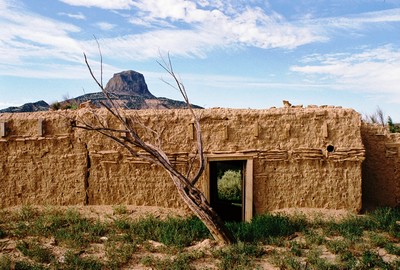

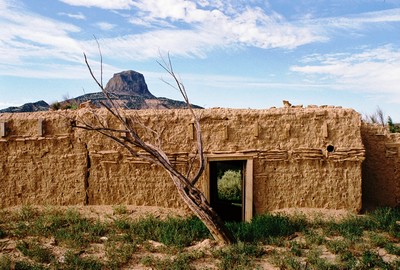

I was told this old adobe was once the Cabezón Bar and Dance Hall. It's hard to imagine now, but if you listen hard you might still hear the clack of boots against the floor.

Before it was Cabezón, the village was known as Rancho de la Posta, or La Posta. “The post” indicated a stage stop, and, indeed, La Posta was on a major stage route west of Santa Fe, and at the crossroads of a trail running between Zuni Pueblo and Jemez Pueblo and a Spanish trail from Albuqueque to Cuba. This confluence of trails makes sense given that Cabezon Peak was and remains an obvious landmark for travelers. However, the area was not permanently occupied until 1872, when the Navajo Reservation was created and skirmishes with settlers ended.

When a post office was applied for in 1879, Rancho de la Posta became Cabezón Station and then just Cabezón. The village thrived for many years, and by 1920 the population may have been as high as 250. There was a church, four stores, several dance halls, the aforementioned post office, some saloons, and dozens of homes. Restie Sandoval, born in Cabezón in 1929 and quoted in Ghost Towns Alive by Linda G. Harris, said, "We had no money, but we were content."

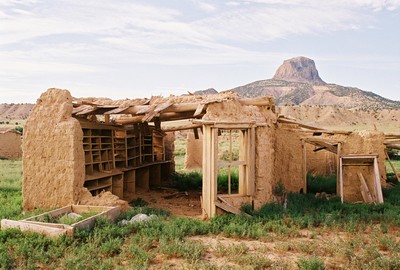

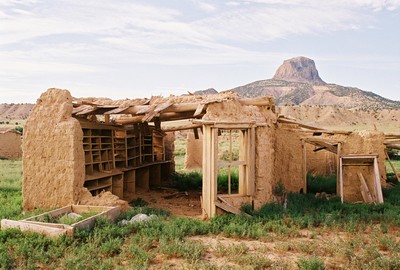

One of the villages’ showpieces was an eleven (or possibly fourteen, depending on who you ask)-room adobe residence occupied by Richard F. Heller and his family, just a few steps across the road from his store. The house also served as hotel, frequently providing lodging to weary travelers. It may yet shelter the occasional bird or rattlesnake, but guests arrive only rarely these days and none stay the night.

A small section of the Heller family’s 11/14-room adobe home and hotel.

Richard Heller was perhaps Cabezón's most prominent citizen, arriving in 1888 and, with partner John Pflueger, buying the trading post that William Kanzenbach and Rudolph Haberland opened in 1874 and ran until they went deep into debt with their supplier, the Charles Ilfeld Company. Heller helped Cabezón flourish, in part because of trade with the Navajo. Heller and Pflueger were brokers for the wool the Navajo brought in, and some years they would take as many as 40 wagon loads to market in Albuquerque. Heller bought Plueger out in 1894, a deal that perhaps included the 10,000 sheep they owned together, and he remained among the village's leaders until his death, establishing a bit of an empire that would also include 2,000 cattle.

The store ruins that can be seen in Cabezón are not those of the original 1874 trading post, but are of a general store built by Heller in 1910 or 1911 that featured "fancy" turned posts on the front porch and a corrugated tin roof. You can still see the cut-outs in the awning, or “cotes,” for pigeons, which Heller was fond of keeping.

Heller’s family occupied the 11-to-14-room adobe house until shortly after his death in 1947. He'd been living in the village for almost 60 years. By that time, trade with the Navajo had ended and drought had come. For those that raised sheep and cattle, competition for grazing rights after the government purchased the adjacent Ojo del Espíritu Santo Grant in 1934 had driven many out of business. Also, in the early 1940s, four brush-and-stone dams on the Rio Puerco had broken during a flood, and with most men fighting in WWII or working elsewhere, there was no one to repair these dams, which had diverted water into irrigation ditches. Heller's widow kept the post office open for more than a year on her own, but then moved to Albuquerque. So, by 1950, Cabezón was largely vacant and left to begin a slow decline that has continued to this day.

There are many iconic photos of Heller's general store in ghost town books, some shots even taken from the rustic porch. However, the years have not been kind to the building.

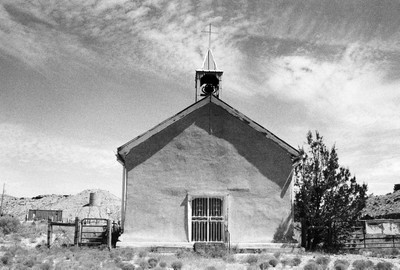

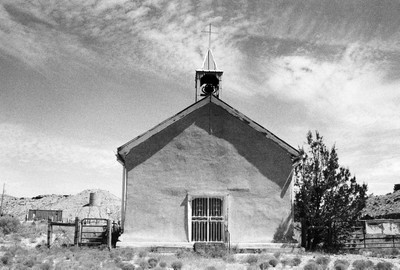

Another thing that Heller did was help get a church constructed in Cabezón. La Iglesia de San Jose was built in 1894, and in many ghost town books it appears abandoned and forlorn, as it was for decades. It had been used as a barn and vandals were once caught tearing up the floor in a hunt for treasure. But in the late-1970s, the church began to be restored. I've heard that Peter Fonda bankrolled the work immediately after directing the film The Hired Hand in the village, but that movie, which starred both Fonda and Warren Oates, was released in 1971. So that seems unlikely, to say the least. In any case, you can get a closer view of a much more intact Cabezón in that excellent Western.

The San Jose Catholic Church was built in 1894.

The real story is that, in 1978, Father John Sauter from up the road in Cuba, New Mexico, wanted to restore the church before its 100th anniversary, which would occur in 1994. So local folks rounded up volunteers to fix the roof, received donated materials, and, over the years, basically did the job with no money at all. Five hundred people attended the centennial celebration. It's worth mentioning that, in addition to the treasure hunters, thieves were once caught trying to steal the church bell. The bell was then put in safe-keeping until it could safely resume its rightful place, which, as you might sorta be able to guess from the photo above, it has.

In his 1981 book, New Mexico's Best Ghost Towns: A Practical Guide, Philip Varney said that Cabezón was, in fact, New Mexico's best ghost town, featuring the most impressive mix of buildings, scenery, and desertion. He also championed Cabezón for the difficulty involved in just getting to the place. Forty-two years later, it’s still difficult to visit (more on that in a moment), and the lanscape is just as scenic. But does Cabezón remain the state’s best ghost town? Well, I'd say…probably not. Of course, Heller's store, the historic centerpiece of Cabezón, has mostly collapsed. A two-story building from The Hired Hand set which, while not historic, did lend ambiance, is totally gone. Most of the adobe homes are badly crumbled and fading fast. Only a few stones stand atop each other of what was the school. The church is actually in better shape than in 1981, but I suppose that just makes Cabezón feel slightly less deserted.

With its many shelves and cubbies, this adobe was probably the post office.

Sure, much of Cabezón's decline is due to neglect and vandalism, but remote ghost towns don't typically have the tax base for neighborhood upkeep, and untended adobes will eventually return to Mother Nature. So I try to get while the getting is good and, as with most things in life, I don't expect permanence in ghost towns. In truth, I was lucky to “get” at all as the property in Cabezón is still owned and the village occupied by one resident who does not exactly desire visitors. In the 1960s, squatters moved into the empty homes and looted them and, as a result, the county comissioner would eventually authorize closing Cabezón. So let’s just say some strings were pulled to open gates, both metaphorical and literal, and make my trip possible. And that was a number of years ago now. Eight years, to be exact.

If you've been to the Cabezón area you might wonder where the timber was found for the buildings. I've read that the vigas were hauled from the forest surrounding Mt. Taylor, a distance of about 10 miles. I guess Mt. Taylor was the closest you could get to a Home Depot at the turn of the 20th century. The stones were gathered from the adjacent hills. I was also told that, much more recently, a woman and her child were in Cabezón and entered a structure when a viga fell, striking the mother and necessitating a trip by helicopter to the hospital. Thus on my visit I was explicitly asked not to enter any buildings. So that is why you see no interiors here.

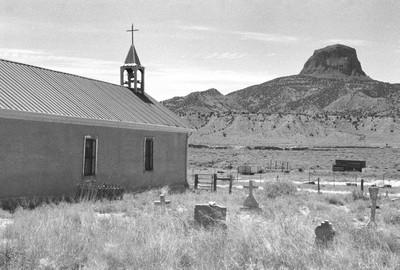

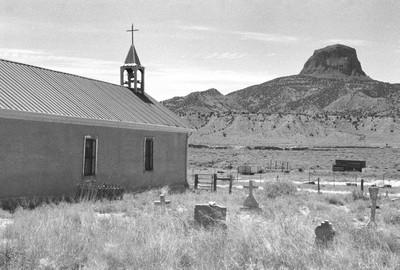

You can almost feel wagons full of wool moving slowly along the Rio Puerco, below Cabezon Peak.

Let’s wrap up our visit to Cabezón with a couple Wild West tales. The Puerco Valley has always been isolated, and so it was that, according to Ralph Looney’s Haunted Highways, in a turn possibly inspired by Jack D. Rittenhouse's rare, Outlaw Days at Cabezon, New Mexico, the village harbored a bandit now and then. In 1884, the Castillo brothers’ notorious band raided the cattle herd of the original owners of the trading post, Kanzenbach and Haberland. A man named Juan Romero tried to stop the rustlers and was shot dead. Kanzenbach organized a posse and a gun battle ensued. The thieves, however, escaped.

After another encounter and escape, the rustlers entered Amadao Lucero's store in Espanola to have dinner. Here the posse was lying in wait. Deputy Montano couldn't get a bead on Candido Castillo's head while the man ate because of a poorly-placed kerosene lamp, so he motioned for Lucero to move the obstacle. A moment later Candido leaned over to light his cigarette with the lamp just as Montano shot, hitting Candido in the side. The Deputy also shot Candido's brother, Manuel, but the two managed to get out the door, somehow melting into the night.

The quiet cemetery of the San Jose Catholic Church.

In the morning, the posse followed the bloodstains, but they ended abruptly at the railroad tracks. The rumor then arose that the brothers, reportedly also members of the Penitente Brotherhood, had happened upon a Good Friday procession and were taken into hiding. Candido was said to be dead by Easter Sunday, but when his grave was opened the body had been removed.

Looney tells of a gruesome ax murder in Cabezón, as well. One day the postal inspector came to town because there was a small discrepancy in cash at the post office, which was run by Emiliano Sandoval. Nobody would say a word to the inspector until he found Juan Valdez at the edge of the village. Valdez said that Sandoval did it. After all, who could've pilfered the money more easily?

A crow’s eye view of the ghost town of Cabezón from atop Cabezon Peak.

The following night, Valdez was sleeping in his home, his two sons nearby, when several residents of Cabezón entered. When they left it’s said that Valdez had been beheaded. Sandoval County officials quickly arrested Emiliano Sandoval and two others, Albino Gurule and Antonio Gonzalez. Gonzalez, having an alibi, was soon freed. Sandoval and Gurule were kept in custody for a while, but eventually released. The crime was never solved as far as I can tell. Not that it’s uncommon for ghost towns to keep their secrets. On that note, I’m sure Cabezón has more to tell, but this is about all I’ve been able to uncover. If you have more to add, please leave a comment below!

Above is one last look at the landscape of the Rio Puerco drainage with Cabezon Peak looming in the distance. This Puerco, flowing through Rio Arriba, Sandoval, Bernalillo, Valencia, and Socorro Counties before meeting the Rio Grande, is sometimes called the Rio Puerco of the East. Yes, there is another Puerco in New Mexico. The second Puerco, usually called the Puerco River, flows through the northwestern part of the state and into northeastern Arizona, terrain which includes the Painted Desert. That is another spectacular southwestern landscape, but one for another day.

First, thanks to those who got me into Cabezón all those years ago. You know who you are! If you want to know more about life in the Rio Puerco Valley, I can't recommend Nasario García's memoir,

Hoe, Heaven, and Hell: My Boyhood in Rural New Mexico highly enough. While Mr. García lived in Ojo del Padre, near Guadalupe, he provides a wonderful picture of the entire region, and Cabezón does get some brief mentions. One of the most recent sources for Cabezón history, and certainly among the best, is Ghost Towns Alive: Trips to New Mexico's Past by Linda G. Harris. But even that is 20 years old now. I also got a lot of the information from Philip Varney's New Mexico's Best Ghost Towns: A Practical Guide and Ralph Looney's Haunted Highways. Surprise, surprise. Both books also have excellent pictures of Cabezón from the days when more was standing. Days that will never come again! I should also mention Robert Julyan's The Place Names of New Mexico, which always has something interesting to offer. I have never seen Route 66 guru Jack D. Rittenhouse's Outlaw Days at Cabezon, New Mexico (limited to 150 copies), nor his more general history, Cabezon: A New Mexico Ghost Town (limited to 750 copies), so if you've got one of either lying around that you'd like to send my way, please do!

That's it! If you made it to the final words of this epic post, thank you very much! I have no idea where we're going next time. I'll have to figure it out.

Let's take a trip to the San Jose Mission at San Acacia, 14 miles north of the town of Socorro, in sprawling Socorro County, which spans a chunk of the central part of New Mexico. San Acacia—originally (and sometimes still locally) known as San Acacio—was established around 1880 when the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railway came through. In “The Place Names of New Mexico,” Robert Julyan notes that the name of the village may have come from San Acacio (aka Saint Acathius), a Roman soldier said to have been martyred with 10,000 other soldiers in the 2nd century A.D. In New Mexico, San Acacio can be found in the work of some santeros on a crucifix wearing the uniform of a Spanish soldier.

When the post office opened in 1881, the “o” had become an “a,” probably because the Spanish was misunderstood. (Note that "San" did not become "Santa.") As far as I know at this moment, the post office remains in operation, but on the west side of I-25, adjacent to the village of Alamillo. Incidentally, an alternative and, Julyan implies, less likely explanation for the name, is that it derives from the acacia bush. If you want to feel like you know the area, go ahead and refer to it as “San Acacio.” You may have some interesting converations!

The mission church may still get some unofficial use.

After a flood in 1886 destroyed the church in nearby La Joyita, an adobe mission church with large vigas was soon built in San Acacia, which also sits close by the west bank of the Rio Grande. About 40 years later the historic flood of 1929 sent residents fleeing for their lives, destroying much of the village, and washing the church away. A section of the village dating from the early 1900s is said to have survived the flood and can be seen to the northeast of present-day San Acacia, but I haven’t gone hunting for that.

A few years after the 1929 flood, through the donations of the Crabtree family, who operated a lumber yard and hardware store, the mission church was rebuilt. That one was destroyed in a flood in 1937. So for the next ten years the people of San Acacia went to the church in Alamillo, a bit farther from the river and presumably generally drier. The current mission church was built after WWII and used officially until 1957. Based on what I’ve seen it may well be used unofficially to this day.

A little artwork has been added to the adobe walls.

In all the years I’ve been visiting San Acacia and posting photos of the mission church (and its likeness in the nearby cemetery; see below) I’ve never heard from anyone that was there when it was having services. Until recently, that is! The recollection I received is so wonderful that I'm going to include it here in its entirety. Memories such as these are hard to find, and I'm always honored to receive another. Many thanks to Ed Baca for sharing his remembrance of a fiesta vespers service:

"I am indeed familiar with the San Jose Mission in San Acacia. My dad's job with the U.S. Geological Survey involved measuring the flow of the Rio Grande on a daily basis. One of his work sites was the gauging station just below the San Acacia dam. As a kid (I was born in 1945), I would often accompany him to San Acacia during my summer vacation. We would pass by that church on the way to the river. While he did his steam-gauging thing, I angled for channel cat at the river's edge.

The church has now passed many falls without congregants.

"As a student at Hilton Mt. Carmel School in Socorro, I served Mass as an altar boy at San Miguel Catholic Church. The spiritual needs of the mission churches in the Socorro area were served under the auspices of the Pastor at San Miguel. Besides the occasional funeral of a community member, small missions like San Jose only had one major service during the year, and that was on its namesake's feast day, i.e., its fiestas.

"Around 1957 or so, I, along with another altar boy, and the San Miguel organist and two choir members, accompanied Father James McNiff to San Acacia to celebrate the San Jose fiesta vespers service. The mayordomos and the community's faithful had lighted the path to the church with luminarias. The organist, my aunt Helen Baca, cranked up the old pump organ at the back of the church. The two choir members sang traditional Spanish hymns to an overflowing congregation of current and former residents who sang along with them.

"The memory of this occasion warms my heart to this day. I know that you know that this unique aspect of New Mexico's Hispanic culture is slowly vanishing, and it is sad. But, thanks to efforts of people to preserve the story of a once-vital place, all will not be totally forgotten."

A likeness of the mission church marks a grave in the cemetery.

A short hike from the moody cemetery, which features grave markers representing both the San Jose Mission and the mission church at Alamillo, and right beside the Rio Grande, is a feature known as Black Butte, where the New Mexico meridian intersects the principal baseline. Placed here in 1855 by John W. Garretson, a U.S. government surveyor, this is also known as the “initial point,” on which land surveys for New Mexico and southwest Colorado are based. The rocky surroundings of the "initial point" are said to be the preferred home of more than a few rattlensakes, as well.

This area was also where the Piro Indians lived. Juan de Oñate, the Spanish conquistador, encountered them in 1598 as he came north with his expedition. The Piro would scatter during the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 and never return to their former home, but evidence of their Puebloan culture can still be found along the Rio Grande.

If you could read any of the markings on this monument, you'd find "initial point" among them.

Finally, I would be remiss in not mentioning Acacia Riding Adventures, which runs horseback trips out of the old San Acacia schoolhouse, right across from the church. That sounds like a fantastic way to explore this section of Socorro County, and just a lot of fun in general. You can find more info at their WEBSITE.

This grave is marked by a representation of the mission church at Alamillo, which was built in 1928.

I grabbed some information for this post from Paul Harden’s excellent “Mission Churches - Part 2: The Mission Churches in Socorro County." (There’s a Part 1, as well!) You can find a little more about the intricacies of the New Mexico meridian and baseline at WIKIPEDIA.

Alright, that’s all I’ve got for this, the THIRD new blog post since…well, October of last year. But that’s better than the last couple years combined! Thanks again to Ed Baca for his generosity in allowing me to share his story far and wide. I think maybe we’ll go to Cabezón, in the Rio Puerco Valley, next time!

During the years of the Civil War, with most able-bodied men sent off to the fray, traversing the Santa Fe Trail became even more treacherous than usual. Without the armed accompaniment that travelers had come to rely on, Native American tribes found it easier to attack settlers and traders moving along the trail, including those on the Cimarron Cut-off, or Dry Route, as it was also called. This alternate route sliced through what is now the western edge of the Oklahoma Panhandle as it entered New Mexico Territory, and while worryingly dry it often was, it was attractive since it cut 100 miles and 10 days off the Mountain Route. At most times it was also considered safer, avoiding the difficult Raton Pass and its steep 7,835' of elevation. But as attacks persisted along the Cimarron Cut-off throughout 1861 and 1862, the military tried to gain control. Among those in the field was Lieutenant Colonel Christopher Carson, also known as Kit, who was sent out to suppress raids by the Comanche and Kiowa, in particular.

Following a reasonably quiet winter of 1863, that spring found the Apache, Arapaho, Cheyenne, Comanche, and Pawnee assembled along the Arkansas River in numbers so large that the trail was actually closed to travel. The following year, in the spring of 1864, both the Cimarron Cut-off and the Mountain Route were back under steady attack. The military had completely lost control by June, and settlers and wagon trains alike were under fierce assault as the tribes tried in earnest to drive them from the land. In the Dry Cimarron Valley, along what is now the Oklahoma-New Mexico border, stone forts were built on mesas with settlers running to them, rifles in hand, whenever a Native American was seen.

Wagon ruts are still visible on the Cimarron Cut-off.

Raids continued into the summer of 1864, and in the second week of August, Comanche killed five men at Lower Cimarron Springs. On the 19th of that month, near one of the Cimarron springs, an entire caravan was wiped out, with ten men lost and 130 mules stolen. Two days later, 10 trains were attacked near the Middle Cimarron Crossing, and over 100 oxen were scattered.

Late that November, in response to the continued raids, Kit Carson’s regiment went to the panhandle of Texas to attack a Kiowa village in the vicinity of Adobe Walls, the ruins of a trading post once operated by William Bent. Some Comanche and Plains Apache joined the Kiowa for a counter-attack, and with a force of 3,000 warriors drove the 372 federal troops back into the shell of the old trading post. But the regiment had a mountain howitzer, and by that evening the warriors had retreated and the village had been burned. This event would enter western legend as the First Battle of Adobe Walls, one of the largest battles to ever occur on the Great Plains. The brutality continued a few days later when, on November 29, 1864, Colonel John Chivington’s Colorado Volunteers massacred 300 men, women, and children living in a Cheyenne and Arapaho village at Sand Creek in southeastern Colorado.

All that marks Camp Nichols are piles of stones.

However, with the ending of the Civil War on April 9, 1865, soldiers were again available to escort travelers over the Santa Fe Trail, and forts began to be constructed to provide supplies and further protection. Fort Dodge was established in April and Fort Aubrey in September. In between, in May 1865, a short-lived stockaded fortification was constructed near Cedar Springs on the Dry Cimarron. This was Camp Nichols, which may have taken its name from Captain Charles P. Nichols of the First California Cavalry.

Camp Nichols was supposed to be in New Mexico Territory, but ended up in what was then mapped as "Public Land" or "Public Land Strip," three miles northwest of present-day Wheeless, Oklahoma. This area, which was home to the nomadic tribes of the Great Plains, was later referred to as "No Man's Land," and wouldn't become Oklahoma Territory until May 2, 1890.

Little remains of the camp now, which was built by Carson at the order of the Military Command of the New Mexico Territory. Intended to be roughly at the halfway point between Fort Union in New Mexico Territory and the Cimarron Crossing of the Arkansas River, not far from Fort Dodge, Kansas, the camp’s sole purpose was to protect travelers from Kiowa and Comanche raids on what had become the most dangerous part of the Cimarron Cut-off.

The remains of what may have been lodging for a soldier.

Carson, however, liked the high ground at a location beside South Carrizo Creek, about four and a half miles east of the boundary of New Mexico Territory. Here was built a commissary, two-room hospital, kitchen, and officers' quarters, all dug into the ground and enclosed with rock. These would be the only manmade structures ever built along the Cimarron Cut-off during its active years. Two mountain howitzers stood at the edge of the camp. It was garrisoned by three companies from Fort Union who escorted travelers to Fort Dodge on the Arkansas River or Fort Larned, which was also in Kansas, offered shelter, and generally patrolled the trail.

In fact, following a biweekly schedule, troops from Fort Union also escorted wagon trains east to Camp Nichols, at which point Kit Carson’s soldiers would take them onward. When heading west, Carson’s troops would take the trains from Fort Dodge to Camp Nichols and then hand them off to the men from Fort Union.

This photo was taken from approximately the spot where a map indicates Kit Carson, who was in declining health and would be dead within three years, pitched his tent. It's facing the ruins of quarters occupied by Lieutenant Henderson and Lieutenant Richard Russell, who lived here for a time with his new bride, Marian Sloan Russell. You can read about Russell's experiences in her book, "Land of Enchantment: Memoirs of Marian Russell."

The dimensions of Camp Nichols have been given as 200' x 200' or 200' x 300', the latter of which would have to include some of the structures outside the square boundaries of the fortified camp itself, such as the officer's quarters and the kitchen. But however you look at it, Camp Nichols was not very big, and was never a true fort. It didn't last long either. In mid-October 1865, the Apaches, Arapaho, Cheyenne, Comanche, and Kiowa signed the Little Arkansas treaties and, in exchange for peace, were given a large reservation in the Texas Panhandle. The Texans themselves would refuse to honor this agreement and a new treaty would eventually be required.

But in November 1865, a mere seven months after they’d established Camp Nichols, the 300 California and New Mexico troops stationed there abandoned it and marched back to New Mexico Territory. Local tribes destroyed the camp over the winter, and the site has been unoccupied ever since. In 1966, it was placed on the National Register of Historic Places, but most days is visited only by the wind and perhaps a few cows.

It takes a little imagination to reconstruct Camp Nichols.

A big thank you to the Cimarron Heritage Museum based out of Boise City, Oklahoma, who offer a wonderful tour of this part of the Santa Fe Trail. They provided access to this location, which is on private property, and a number of other rare Santa Fe Trail gems. They do it every June, so if you're interested, get connected with them HERE.

The museum also collected some excellent historical information, including a hand-drawn map, for a handout on the site, which is otherwise spread across numerous sources. Another resource was “Window on the Past: Historical Sites in Oklahoma” by Kent Ruth, which reported the size of Camp Nichols, possibly incorrectly, as 200' x 300'. However, the most scholarly account, and one which adds the most historical context, was found on page 127 of “History of the Cimarron Indians.” This obscure volume was unearthed at the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City, which has an incredible western history archive. I thank them for their assistance (and for being willing to take a copy of my own book for the archive!). I highly recommend a visit to the museum itself, but you’ll need an appointment to see the archive.

Other useful Camp Nichols references include The Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture (for both the camp and No Man's Land), The Historical Marker Database (only it wasn't really a fort), Santa Fe Trail Research and, of course, Wikipedia.

Whew. That was a long one! So I'm going to leave it at that for now, except to say that I took all the photos with Fujichrome Sensia 100 35mm color slide film that expired in December 2004. Weird, huh?