(CONTINUED) The next day was Saturday and Ruben and I slept late. I was awakened by my phone ringing. I looked at the clock. It was one in the afternoon. I picked up the phone. It was Anne.

“Tom, I’ve just told Steve everything.” She was talking fast. She sounded scared.

“What happened?”

“He got angry.”

“Did he hurt you? Is he there?” I was already up and groping around for my clothes.

“No, he didn’t touch me. He’s gone now. But he got so mad. I’ve never seen him like that. He told me he loved me. He’d never said that before. He told me I’d hurt him worse than anyone in his life.”

“I doubt that,” I said, grabbing a shirt. “I’m coming over.” I thought she might say it wasn’t necessary, that she’d be alright, but she didn’t. She just said, “Okay.”

I told her I’d get Ruben’s truck and be there as soon as I could. I told her to stay inside and not answer the door. Then I woke Ruben and told him what was up.

“You want me to come with you?” he asked. “In case this guy comes back.” I thought of how frightened Anne had sounded on the phone. I believe I saw her vulnerability as an opportunity. I wanted to play the white knight. I wanted to be with her again. It was ridiculous and wrong and it would’ve been impossible. I don’t know if Ruben could have changed much about the way things went, but he started getting out of bed and I stopped him. It was a mistake.

“Nah, just go back to bed. It’ll be okay.”

Ruben looked at me. He knew something wasn’t right but he just said, “You know best,” and rolled back into bed. “You gonna be able to drive the truck?”

I said I could handle it and he told me to take my time; he’d take the bus in to work as long as I’d pick him up. I told him I’d meet him outside the post office at 2 o’clock. Then I got in the truck and turned the key. The beat-up hulk coughed and spluttered and I worked the gas to get keep the engine going. A cloud of blue smoke rose into the air as I backed out of the drive and headed out to Geary.

Anne still lived in our old house, over in Walnut Creek, right by the BART tracks. It was loud and whenever a train went by all conversation ceased and occasionally something would rattle off a shelf. It was far from ideal, but the noise made it affordable and that was something not to be taken lightly at the time we’d bought the place. To get there from Ruben’s house wasn’t easy. I had to cross the bay bridge and make my way through the East Bay, all the while nursing Ruben’s truck along, sometimes revving the engine at stoplights to keep it from dying. I had the cell phone next to me in case Anne called, but she didn’t. Forty-five minutes later I rolled into the driveway, pulled my foot off the gas, and the truck shuddered as the engine died. I was out the door and up the walk before the thing had stopped making noise. I still had my key to the front door.

Anne was standing in the kitchen holding a glass of wine. She’d been crying. She came from behind the counter and put her arms around me. She didn’t say anything, I just held her. It felt wonderful. In the distance I could hear the BART, the low whoosh off to the east. The windows began to rattle a little as the train approached. I pulled Anne closer and she put her head on my shoulder. I could feel the warm, wet tears on my neck. I stroked her hair. The train was right outside and I recall thinking that maybe one of the BART tracks had come loose or perhaps one of the cars had hit something because I heard a loud “CRACK.” Then all at once Anne gasped in a funny way and sagged against me. I held her upright and felt a strange, wet warmth against my belly. It was then that I saw the blood dripping onto the carpet. I eased her to the floor. Her shirt was bloody and I lifted it over her stomach. There was a hole in her side, between two ribs, and I put my hand over it, as if that would stanch the flow of blood. It did not. The blood seeped through my fingers and ran onto the floor. I began to go for the phone, but Anne was looking at me in a way I’d never seen before. Her eyes were glassy and her face pale. Her lips were drawn; it almost looked like she was smiling but she was not.

She took my bloody hand in hers and squeezed it. “Just hold me,” she whispered. I gathered her in my arms, kissed her, and began to cry. It was probably less than a minute before she died. I pulled her close to me and sobbed. I kissed her again but she was gone. It was then that I saw him. I believe that he must have fired the shot from just outside the open patio door, which he’d probably unlocked before leaving the house, but by the time I looked up he’d already stepped inside. He was holding the gun in his right hand, which was trembling slightly, and staring at Anne. I thought he would shoot me, but instead he fell to his knees and put the gun to his own head. I laid Anne’s body down, stood up, and took two steps toward him. “Pull it, you sonofabitch!” He looked at me with wide eyes and pushed the gun harder into his temple. I grabbed a poker from the hearth and held it over my shoulder with both hands, like a baseball bat. “Pull the fucking trigger!” The eastbound BART train was leaving the station. I could feel the vibration. I took another step toward him. I knew he could just as easily shoot me but I didn’t care. “Do it or I’ll do it myself!” The windows began to rattle and his hand started to shake terribly. He closed his eyes and began to squeeze the trigger. The BART train was just beyond the yard. The gun went off and he looked at me wild-eyed. His right ear was gone and bits of plaster were drifting down from the ceiling. My own ears were ringing. A stream of blood flowed down his cheek. He opened his mouth wide and I swung the poker at his head. He fell onto his back and his face turned toward me. His eyes rolled back in his head; I don't know if he saw anything else or not. He did not cry out nor did he try to defend himself as I brought the poker down again.

She took my bloody hand in hers and squeezed it. “Just hold me,” she whispered. I gathered her in my arms, kissed her, and began to cry. It was probably less than a minute before she died. I pulled her close to me and sobbed. I kissed her again but she was gone. It was then that I saw him. I believe that he must have fired the shot from just outside the open patio door, which he’d probably unlocked before leaving the house, but by the time I looked up he’d already stepped inside. He was holding the gun in his right hand, which was trembling slightly, and staring at Anne. I thought he would shoot me, but instead he fell to his knees and put the gun to his own head. I laid Anne’s body down, stood up, and took two steps toward him. “Pull it, you sonofabitch!” He looked at me with wide eyes and pushed the gun harder into his temple. I grabbed a poker from the hearth and held it over my shoulder with both hands, like a baseball bat. “Pull the fucking trigger!” The eastbound BART train was leaving the station. I could feel the vibration. I took another step toward him. I knew he could just as easily shoot me but I didn’t care. “Do it or I’ll do it myself!” The windows began to rattle and his hand started to shake terribly. He closed his eyes and began to squeeze the trigger. The BART train was just beyond the yard. The gun went off and he looked at me wild-eyed. His right ear was gone and bits of plaster were drifting down from the ceiling. My own ears were ringing. A stream of blood flowed down his cheek. He opened his mouth wide and I swung the poker at his head. He fell onto his back and his face turned toward me. His eyes rolled back in his head; I don't know if he saw anything else or not. He did not cry out nor did he try to defend himself as I brought the poker down again. I don’t know how many times I hit him nor do I know how long I kept at it. I may have screamed and yelled and wept in rage and wild sorrow. Or I may not have. I remember dropping the poker and hearing it thump against the bloodied beige carpet. I remember seeing blood and brain matter on my clothes. I could not have identified the man lying before me. Nor, do I believe, could I have identified the man standing over him, gasping for breath, murder freshly stamped upon his life. I went to Anne and lay down next to her. I pulled her to me and put a hand over her stomach, beneath which our child lay dead. Then I may have slept because I remember a moment when I believed it all to have been a terrible dream. But before I even opened my eyes I could smell the blood and the sour taste of death was on my own skin.

It’s strange to want to die and yet find yourself taking every measure to prolong your own survival. Yet this is what I did: I looked out the front window and saw no one out on the street. The backyard was also empty. I locked the patio door and dead bolted the front and back doors. Then I pulled the curtains closed. I took off all my clothes and put them in a garbage bag with the poker. I found some of his clothes in Anne’s bedroom and then took a shower. For a few seconds the water ran red as it spun down the drain, but three minutes later I was clean and wearing the clothes of a man whose whole history I wished wiped from the face of the earth. I put the towel in the garbage bag and then, if I could have, I would’ve laughed. My fingerprints were all over the house and all over Anne, indelibly traced in her own blood, my hands on her skin. And even had I not been standing in that room at that moment I would have been a suspect. I looked at the mangled body of the man on the floor. I didn’t know if the police would believe my story. I knelt down and touched Anne’s cheek. I told her I was sorry. I did not want to stand trial for what I’d done regardless of the sentence or the mitigating circumstances I might be offered. I was guilty of many things. I would have to run.

I dumped the garbage bag upside down and left the poker and clothes soaked in gore upon the floor. I would run but I wouldn’t hide. I took the garbage bag with me. I got in the truck and was just to the stop sign at the end of the road when my phone rang. Julie McGregor. I didn’t answer. I was already on my way to Santa Fe. (CONTINUED)

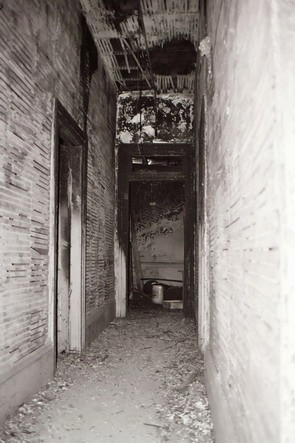

Photos taken in an abandoned rooming house on Greene St., Augusta, Georgia.

Great Story Blook you have going! You have a terrific sense of story. Keep up the good work.

ReplyDelete