skip to main |

skip to sidebar

(CONTINUED) Nineteen

“Dane was always a little haunted after that, I think.”

Mary and I were seated at her dinner table, a dark, heavy piece made of thick wood that could’ve been 400 years old for all I could tell. We were eating enchiladas made with freshly mashed pinto beans and hot green chiles. Just before serving Mary had topped each of our plates with a fried egg. The food was delicious. The conversation, however, had quickly become morbid, reminding me of my own roiling hell. Mary went on: “Although, I don’t believe there was any reason for him to blame himself for Oscar’s death.”

Almost immediately after sitting down Mary had begun to tell me how wonderful it was to once again have some company at the dinner table. This led to a description of her late husband’s long battle with cancer and, working backwards in time, she’d now arrived at the point when Oscar, their only child, had hung himself from the garage rafters at the age of 15.

“So tell me, Mr. Gould, what are your thoughts on suicide?”

I put down my fork and wiped my mouth with my napkin. The truth was, I had thought about suicide a fair bit over the last few days and maybe even for longer than that. At times I’d probably even thought it a pretty good idea. “Please, call me Tom,” I said, and then drank some wine. I didn’t know what to tell her. I could look at it philosophically; I could discuss it from a religious point of view; I could describe the torments of countless artists--some of whom I’d known--and their desire to end a ceaseless pain. It was all bullshit. “I don’t know that I have any thoughts on suicide,” I finally replied. Mary looked at me strangely. For a moment I thought she may have smiled. I continued: “Or, I should say, I don’t have any thoughts on the suicide of others. I don’t believe we can blame a person for taking their own life. And don’t I believe anybody should blame themselves because someone they know has taken their own life.”

“Even one’s child?” Mary asked.

I paused. This conversation with my new landlord disturbed me. “I suppose it’s impossible for a parent not to blame themselves. But some people just get wired wrong, I guess.”

She refilled my glass. “So, you think a predisposition for suicide is genetic?”

I did indeed, but I wasn’t sure I should say so. I felt like I was taking a test that I’d better pass, even though I didn’t know what the penalty would be for failing. I began to say something, stopped myself, picked up my glass, put it back down, and finally said, “Maybe.”

She was quiet for a few minutes. I went back to my enchilada and hoped that I’d heard the end of the topic.

“But what about your own?” Mary had hardly touched her food and it was growing cold. Now she was staring at me intently.

“Excuse me.”

“What are your thoughts on your own suicide?”

I just looked at her, holding the fork in midair.

“I was just wondering. You said you didn’t have any thoughts on the suicide of others. I was just wondering if you had any thoughts on your own. Would you ever take your own life?”

I put the fork back down. I looked directly at her. “No, I wouldn’t.”

“Can you be so sure?”

I’d just turned back to my plate and put the last bite of enchilada in my mouth. I nodded while chewing: “Yeah, at this point I think I’m pretty certain of that.” I knew I was finally telling the truth, but there was no satisfaction in it. Mary started to ask something else and I put out my hand. “Please, can we not talk about this anymore?”

She laughed loudly and I was a little startled. “I’m sorry,” Mary said. “I thought all writers liked to talk about these things.” I couldn’t tell if she was making fun of me.

“No,” I replied. “We just like to write about them.”

Mary laughed again and stood up. “I’m just an old woman and I think about death too much. You don’t worry about it much when you’re younger.”

I knew that wasn’t true, but I wasn’t about to get into it.

Twenty

That night I went to bed in what had probably once been a guest room. It was off the hallway on the second floor and had a dresser, desk, and queen-sized bed. The bed was the most comfortable I’d had since well before showing up in San Francisco to sleep on Ruben’s couch. Even so, I didn’t sleep much more than two or three hours. I would’ve been surprised if Mary had slept anymore than me. Throughout the night I heard her padding down the hall. I heard the stairs creak as she went downstairs. I heard her mutter to herself as she came back up. At one point I thought I heard a radio go on. We were a fine pair.

In the morning I laid in bed and listened to Mary make herself breakfast. I felt like my life had been cleaved in two. Everything that had happened up until the time I’d arrived in Santa Fe belonged to one person and everything since was something different, without history or precedent. I knew it was only an illusion but the sensation was so strong it made me feel like I was losing my grip on reality. On the other hand, it was this very break that made it possible to function at all. What’s more, the things I was doing and the situations I was finding myself in did not seem to be without meaning. I had woken from a nightmare into a dream.

I heard the door shut as Mary left and once the sound of her car had faded down the road I got up. I went downstairs and there was cereal, fruit, and bread arranged on the table. A note was nearby: “Tom, please help yourself to anything you want. Juice is in the fridge and the coffee maker is ready to go. Just turn it on.”

I flipped the coffee maker on and sat down at the table. It really was like a dream. Then I remembered something. I went back upstairs and checked my phone. There were two calls from Ruben and one from my agent. It had been a long time since I’d heard from my agent. Ruben’s message was first: “Tom, I know you didn’t kill Ann. But you have to do something. It’s on the news. They’ve got your name, your picture. You have to come back. That guy killed your wife; people will understand.” I doubted that people would understand. The message from my agent was next: “Tom, what the hell…” He was already out of breath, almost screaming. I hit delete. The last message was from Ruben but there was nothing and then a beep. It didn’t sound good. I changed my outgoing message to: “You’ve reached Tom Gould. Please leave a message.” This was mostly in case Julie tried to call. I had no intention of ever answering that phone again.

I went back downstairs and had some coffee and a banana. The banana was hard to eat and the last few bites almost made me retch. I brought my coffee upstairs and took out the notepads and pens. I sat at the desk and looked at them. From memory I began to write out a short story by Chekhov about a man who takes shelter from the rain under an upturned boat on a beach. When he crawls inside he sees that a young woman has also taken shelter under the boat. At first they are shy and tentative and speak only with hesitancy and brusqueness. But soon the man hopes the rain might never stop. When it finally does neither seem to want to leave the shelter of the boat, but finally the woman tells him she must get back home. She crawls outside. The man remains under the boat for awhile longer, feeling that something very important is being lost through nothing more than his own willful rejection of it. He does not move. At last he comes out into the early twilight. He does not even know the woman’s name. He will never see her again. Perhaps his life has been ruined. At least, that was the way I remembered it. What I couldn’t recall I made up. I left the notepad on the desk and hoped that Mary wasn’t too familiar with Chekhov.

I spent the rest of the day walking around town, wondering if my fate was being decided for me at that very moment some 1200 miles away. I wondered if it was only going to be a short time before someone showed up in Santa Fe for no other reason than to find me and bring me back to San Francisco to stand trial for murder. Or would they make me stand trial for two murders? Or three? Every time I sat on a bench or went into a café I began to expect the inevitable hand on my shoulder. “Mr. Tom Gould? You have the right to remain silent.” I thought about running but there was nowhere else worth running to. It was like I’d suddenly found a home, entirely unexpectedly and undeservedly. If it wasn’t going to last for long I was going to try to forget about both the past and the future and live only for the moment, the only thing that wasn’t run through with dread and regret.

At 5 o’clock I walked into the Golden Horse. I said hello to Mary, who was sitting at a desk by the door, and, though I had not told her that I would be stopping by to meet Julie, she said, “Just a second. I’ll go tell Julie you’re here.” It made me apprehensive to know they might be talking about me, but it also made me smile. Worse things were being said about me at that moment, of that I was certain.

Julie came out from the back wearing a kerchief on her head and holding a tape measure. “I was just framing a new piece. I’ll be out in a second.”

I browsed around the gallery, a man who days before had held his ex-wife in his arms while she and their baby died; a man who had beaten another man to death with a poker; a man who was a fugitive from the law; a man waiting to take a girl he barely knew out to dinner, to bring her into his life. Yet I felt powerless to do anything else, to change the fate I was moving toward. My life was no longer my own.

“Okay, let’s go.” She’d come up behind me and put her hand on my shoulder. I actually jumped off the floor. She stared at me, eyes wide, bemused.

“I’m sorry. You startled me. I was so absorbed with this piece.” I gestured toward the painting, a poorly-wrought oil painting of an adobe church.

“Really?” asked Julie. “I’ve never thought much of that picture. It’s been here for ages.”

I had no response, so I said, “Well, I guess art is in the eye of the beholder.”

Julie laughed and I followed her out the door. “Where are we going?” I asked, as we walked down Canyon Road.

“The Pink Adobe.”

Now I laughed. “Rubbing it in my face, eh?”

“On the contrary. I thought it would be cute.”

I hadn’t been certain if this evening was meant to be a date or not. To be honest, it hadn’t really mattered to me and I’d given it little thought. But now I was certain and it did matter to me. But I wasn’t really sure I wanted it to be a date.

Julie talked about her day as we walked and I said that I’d written a story and immediately regretted lying to her. She asked me what it was about and I took a deep breath and repeated the Chekhov tale. I was relieved when she told me she thought it was beautiful, but I knew it was a bad start to the night.

Inside the Pink Adobe it was dark and we got a small, rickety table in a corner. A little light came in through a curtained window farther down the hall, but our table was mostly lit by a single candle. Julie looked gorgeous by the flame, her grey eyes seeming a little sad even when she smiled. She pulled her hair up and had even put on a little lipstick; I hadn’t noticed that when she’d surprised me at the gallery. I started to hate myself again.

“So,” she began, “are you originally from San Francisco?”

“No, I’m from Boston, but I moved to San Francisco many years ago.”

“Where does your family live?”

This was going to be difficult. I didn’t know if I should lie or tell the truth or simply mix the two together as seemed convenient. I spoke the truth and lied by omission: “My parents are dead. My father got lung cancer from working with asbestos—he worked construction—and died in his early fifties. Without him, my mom went pretty quick. I’m an only child and we never really got together with any of my other relatives when my parents were alive.” The waitress brought us our menus and two glasses of water.

“An orphan,” said Julie.

“Yeah, I guess. Not a very happy tale, eh?” I didn’t want her to ask a follow-up, so I said, “And you?”

She smiled. “Santa Fe, born and raised. I’ve got a younger brother, which you know, and my mom lives nearby. I never really knew my father. He left when I was pretty young. My brother had just been born. Not a very happy tale either, huh?”

“Family stories rarely are.”

We took a few minutes to look at the menus and when the waitress returned I ordered huevos rancheros and Julie had a vegetarian burrito. We went back to small talk for a bit and then Julie stopped and looked at me sort of funny and grinned. Then she said, “Mary thinks you’ve been married.”

My stomach dropped. I searched for a word, any word, really, but could say nothing. All at once I missed Ann so badly I thought I might start weeping. Julie must’ve noticed something was wrong because she started to apologize.

“It’s okay,” I finally managed to say, though it was not okay.

For a while we were both silent. It seemed like there was nothing else to say, like there might be nothing else to say between us ever again. I searched for words and said the first sentence that managed to cohere: “So, are you seeing anyone?”

She looked at me, slightly bewildered. I knew immediately that it was a stupid thing to have asked.

“No,” she said. “I was seeing this guy a couple months ago but I ended it. He was really boring in bed and I’m up for just about anything.”

I felt embarrassed and as she started to go on I held up my hand. “This kind of talk makes me uncomfortable.”

“Why?”

I looked at her, lit by the candlelight, worrying an earring. I wouldn’t think of laying a hand on her. “Because, you’re so…so…”

“So what?”

“So young.”

Her eyes got wide and then she leaned back and laughed so loudly that diners at the three nearest tables all turned to look at us. When she could finally speak she said, “Tom, how old do you think I am?”

I gestured vaguely. I found I couldn’t even offer a guess.

“I’m 28,” she said. “I’ve been drunk, had sex, smoked pot and even”—she gestured at her left ring finger with the thumb of that hand—“been married and divorced.” She laughed again. “But thanks—that was sweet of you.”

I’d often made this mistake in my life; taken beauty for innocence. But beauty untested, untried, was not beauty at all but simply weakness waiting to be devoured. That which would be beautiful must know ugliness, despair, hatred, and pain and then, only once submerged in the flames of the world and risen again, can it appear as true beauty. Thus, beauty is never for the young. I was so embarrassed I blushed and hoped that, in the darkness, she could not tell.

Julie laughed some more and wiped her eyes and asked me how old I was. “Thirty-five,” I said, “going on 80.”

The waitress brought our food and we ate quietly, talking every now and then about childhood memories or trips we’d taken. Julie began to talk about her Catholic upbringing and how important religion had been to her mother. She said that she still prayed all the time and asked if I ever did.

“As a boy I prayed hard for just one thing,” I said. “But I haven’t prayed since.”

“So your prayer wasn’t answered?”

I smiled a little and shook my head.

Julie took a bite of her burrito and chewed it slowly. Then she said, “I think that just because you’re prayers aren’t answered doesn’t mean you shouldn’t keep praying.”

“Is that faith?” I asked.

“Some people might call it that.”

I smiled again. “Some people might call it something else.”

She looked away quickly. I’d made her angry. I tried to make amends: “Hey, I just said it might be something else. I didn’t say I thought it was bad.”

After our meal we walked around in the cool desert evening. The moon hung full in the sky and everything was bathed in the milky light. The air was so soft you could hardly feel it on your skin, a night that could only be had amidst sand and rock and the endlessly unspooling sky. For a time we sat watching the black water of the Santa Fe River flowing slowly through town. Then Julie stood, took my hands in hers, and said that she’d had a very nice time. I told her that I had too and she smiled, somewhat sadly, I thought, and wished me a good night. (CONTINUED)

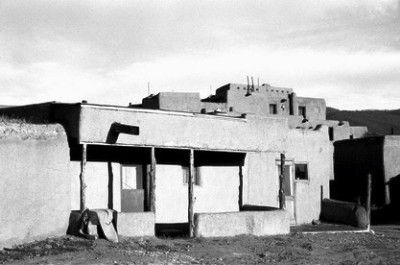

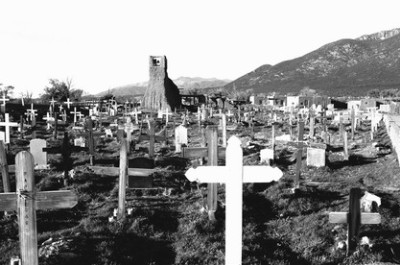

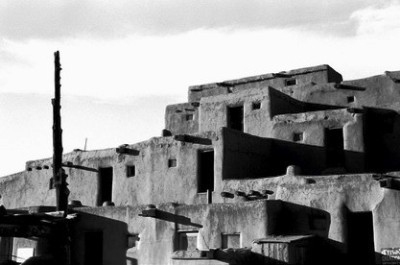

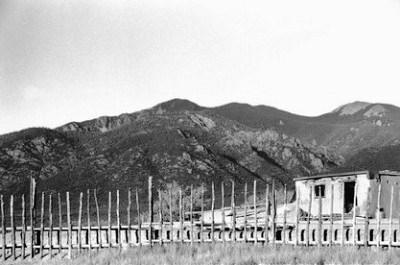

Back in Taos, NM and everything is black and white.

(CONTINUED) Seventeen

After Julie left I checked my phone messages. Ruben had called three times. I decided to listen to the most recent voicemail. He sounded exhausted, exasperated, and scared. “Tom, it’s me. I don’t know where you are or what’s happened, but please get in touch, man. The cops have been here and they asked lots of questions. They’re looking for you. I suppose you know that Anne is dead and so is that guy she was seeing. I didn’t tell the police anything, because even I don’t know if you’re alive or dead.” There was a long pause and I thought he’d hung up, but then he said, almost at a whisper, “Jesus, Tom, what happened?”

I thought for a moment and then set my phone to record a new outgoing message. After the tone, I said, “Ruben, I’m okay. I didn’t kill Anne and I hope you know that.” It was hard to go on and I had to stop for a moment. Then I made myself say, “I did kill him and I’m not sorry.” I could feel the tears in my eyes. “He took Anne and our baby. It was him.” I wiped my eyes and took a breath. “I just had to leave. I can’t face what’s happened. I’m sorry. I hope…” There was a beep and the recording cut off; I was out of time.

I went to my car and sorted through the clothes I’d left inside. Almost everything was filthy. Given my circumstances it was ridiculous, but I drove to a rundown Laundromat off the highway and did laundry. I read old magazines and stared at an ancient television while the washers and driers gurgled and spun. Dr. Phil was on the Oprah Winfrey show talking with three couples. The show was titled, “How to rescue a troubled marriage.” I couldn’t believe it. The picture rolled and popped and went green, then turned to static. Just when I thought the old set had finally, mercifully given up the ghost, Dr. Phil suddenly popped back onto the screen in full Technicolor. I sat there for many long minutes waiting vainly for the static’s return. Then my arms started to itch and I quickly got up off the filthy couch I’d been sitting on and scratched for a bit. It all felt so mundane and surreal that I could hardly believe it. When the dryer was finished I folded everything neatly, but I didn’t have a suitcase so I put it all in a plastic garbage bag.

Outside three kids were looking at my car but they backed off when they saw me approach. I threw my bag in the car and looked for the kids but they were gone so I walked up the street a bit to a bar I’d seen. A worn-out blonde with bad skin and black teeth was standing by the door as I went inside. She said, “Hello,” and I nodded in return. Inside it was dark and smokey and stale, like any other similar place in any town you’d care to name. I sat down and ordered a beer and looked around. There were five men in the bar and two women. Four of the men were alone and one of the women. There was one couple, but they weren’t talking. The jukebox was off and, aside from the soft clink of glasses and bottles, the only other sound came from a television above the bar. I shouldn’t have been surprised that it was tuned to Oprah. Thankfully, the volume was very low and it was impossible to make out the words. There was nothing else to see in the place, so my attention turned to my thoughts and then to my beer and then to another beer. The blonde from outside came inside and sat down next to me. She asked me if I wanted a date and I saw the bartender look at me out of the corner of his eye. I couldn’t tell if he wanted me to say yes or no. I told the girl that I was okay and she kind of slumped over and stared at the scoured bar top, her head in her hands. I slowly finished my beer and then asked the girl, who by then hadn’t moved in five minutes, if she wanted a bottle too. She looked up and said, “Yeah, thanks.” The bartender brought over our drinks and we drank in silence. The girl finished first and stood up. “Thanks again,” she said. “See ya ‘round.” A bright rectangle of sunlight fell across the filthy floor as she stepped outside. Then the door closed and the light was swallowed up.

I had one more beer and, while I wasn’t drunk, I’d taken the edge off things. I was going to need some more clothes, so I went to a department store and bought a few items. I also picked up a cheap suitcase, some toiletries, and a few notepads and pens. I didn’t know how I was going to convince Julie that I was doing any serious writing without a laptop or even a typewriter. I’d have to tell her that I found it easiest to get my words down the old-fashioned way; by hand.

I went back downtown and stopped at a French pastry shop. The girl at the counter spoke to me with a thick accent and I had difficulty understanding her. I felt a little sick to my stomach and I hoped the bread would help. I read the paper. I watched the customers. I counted the tiles on the floor. I tried not to think about anything specific. I was getting better at it. Then I walked around the plaza and listened to the conversations, picking out the tourists and trying to guess where they were from. As a young writer I’d done this kind of thing all the time. Observing. I’d believed that I needed to take in lots of information so that it could be processed and converted to stories. I hadn’t known then that real stories come from within, that they have nothing to do with the world outside or the lives of strangers. I may not have even known that until three days ago and now that I did know it I believed it was too late to do anything with the information.

At ten minutes to five I started walking toward Canyon Road. Julie hadn’t called and I hoped that didn’t mean I’d need to find a place to sleep that night.

Eighteen

I found the Golden Horse easily enough. A swank, upscale gallery, it fit right in with its neighbors. A man in a double-breasted suit walked quickly up the street, a wrapped painting tucked under his arm, a gift for his wife or mistress or ego. A woman stepped out of the gallery across the street holding a bronze cast of three horses. I wouldn’t have doubted that it cost five figures. I just hoped I’d have a couch to sleep on for the night.

I walked into the Golden Horse and had a look. The art was a mix of southwestern-themed tourist-bait--pictures of cactuses and turquoise jewelry--and well-done oil and watercolor paintings of just about anything else. There was a strange incongruity that I’d noticed before in the Canyon Road galleries; overpriced trinkets side-by-side with museum-quality work. There seemed to be no middle ground. I looked for a time at a painting of a girl sitting at a café table, an empty chair across from her, her anxious face lit from a single candle on the table. The picture was titled, “Stood Up,” and it was very good. It was also $9500. A grey-haired woman of about 65 came over to me. She was wearing a turquoise and silver necklace and smelled of rose water.

“It’s beautiful, isn’t it,” she said.

“Yes, it’s quite good,” I replied.

After a few moments she continued: “We do offer layaway, if you’d like.”

I laughed. “I’m going to need more than layaway.”

She smiled, somewhat disapprovingly, it seemed, and I told her I’d just stopped in to meet Julie McGregor.

“Oh!” she exclaimed. “Then you must be the fellow that’s looking for a room.”

“Yes,” I said. “I am.”

“You know, I might have just the thing for you. It’s not much, but it’s got a bed and dresser and I won’t ask much for it.”

“That sounds perfect.” At least one problem was solved.

“Good. Let me find Julie.”

The woman went up a flight of stairs and I looked at a few more paintings. As they came down the stairs, I heard the woman tell Julie, “He can move in tonight if he’d like. It would be nice to have someone around the place again.”

I walked across the room to meet them and Julie said, “Hello, Tom. I see you’ve met Mary.”

“Yes, we’ve met. Although we skipped names and went straight to business.” I offered the woman my hand and said, “Tom Gould.”

“Nice to meet you. I’m Mary Ann Carter—just call me Mary. Julie says you’re a writer.”

“Yeah, as much as writing can be said to be a profession.”

Mary asked me if I’d written anything she might know and I rattled off a few titles. She hadn’t heard of any of them but said she’d see if the library had anything available. I really hoped she wouldn’t because I knew they would. She asked me how long I planned on staying and I told her that I wasn’t sure. That was the truth. Then I told her that it all depended on how the story I was working on went. I thought that might be a lie, but looked at another way it could’ve just as easily been the truth.

We left the gallery and Julie locked up. Mary said that I could follow her to her place and told Julie she could ride with me. I saw Mary wink at Julie but I pretended I didn’t notice. Julie and I walked to the Jag and got inside.

“She seems like a nice lady,” I said.

“Yeah, she’s a sweetheart. Her husband died 6 months ago and she inherited the gallery. Well, she’d worked there for years, but Dane—that was her husband—he’d always done the books. Now I do the books.”

“How are things?” I asked.

“Oh, pretty good. It’s pretty hard to have an unsuccessful art gallery in Santa Fe. But it’s expensive to continually be bringing new work in.”

We drove up Canyon Road for a bit and turned a few times and pulled up in front of a large, adobe house with an exquisitely manicured lawn and a collection of life-size statuary out front. I hadn’t expected this.

“Here it is,” said Mary, as we got out of the car. I looked at the houses nearby and was glad I didn’t have Ruben’s truck anymore. The Jag, on the other hand, fit right in. Julie and I followed Mary into the house.

Just inside the front door was a tile entryway. To the left was a living room with a piano in it and to the right was a long hallway. The walls were filled with painting and photographs and several shelves held a variety of figures and carvings. A massive bookcase stood against one wall of the living room. Mary noticed me looking at it and said, “Go ahead. Have a look. See if you approve.”

I slipped out of my shoes—Mary didn’t tell me to leave them on—and walked over to the book case. James Joyce. Dostoyevksy. Dante. Victor Hugo. The classics. “Mary,” I said. “You wouldn’t happen to be in Julie’s book club, would you?” Julie and Mary both laughed but neither of them said anything.

Julie said she had to run a few errands and I told her I’d give her a ride back down to the plaza. Mary said she’d start cooking supper for us, if I was hungry. I couldn’t bring myself to say no, so I told her not to make anything special and to start running a tab for me.

On the way down Julie told me that Mary was really looking forward to having some company. She warned me that Mary might want to talk about literature and films and art and that if it got to be too much and interfered with my work I could just say so. I told Julie that I didn’t think it would be a problem. As she got out of the car she said, “You know, I don’t really know much about you.”

“That’s true, but I don’t know much about you, either.”

“Should we fix that?” she asked.

“I would like that,” I said, though the thought honestly frightened me.

“Can you be at the gallery at 5 again tomorrow?”

“I’ll be there.”

I drove back up to Mary’s and could smell chiles as soon as I opened the door.

“I hope you like New Mexican food,” she called, as I came inside, carrying my cheap suitcase.

I put the suitcase on the floor; I hadn’t actually been shown my room yet. I went into the kitchen and sat on a stool. Mary asked me if I wanted a beer but I told her I just wanted a tall glass of water. I sat and watched Mary cook and neither of us said much. I felt safe for the first time in what seemed a very long while. I knew it wouldn’t last. (CONTINUED)

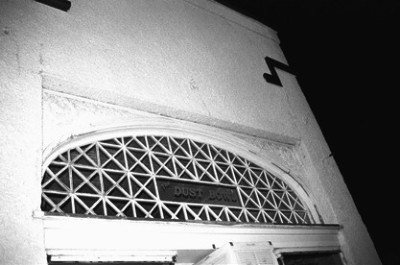

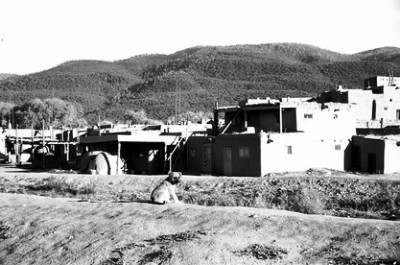

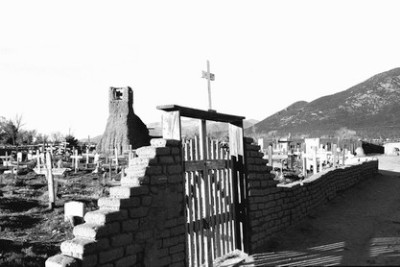

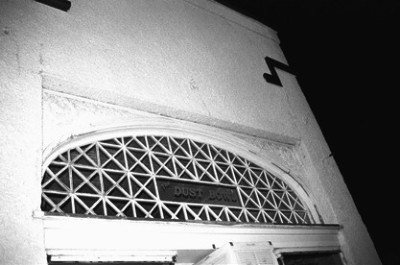

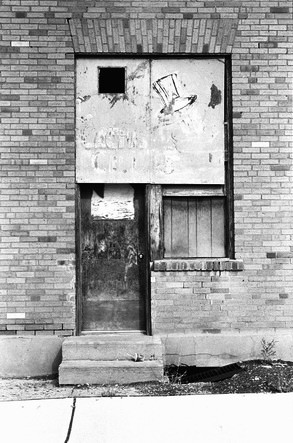

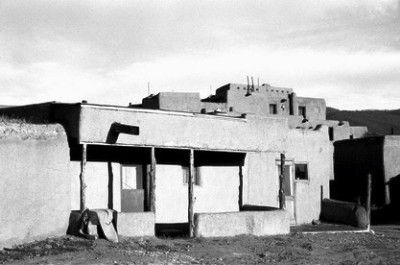

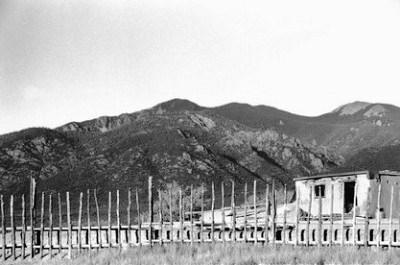

The top photo was taken in Clayton, NM one dark and balmy fall evening. The middle shot is the remains of the Cactus Cafe, Springer, NM. The last shot is Taos Pueblo, NM.

(CONTINUED) Fifteen

Traffic was stop-and-go out of Albuquerque but, unlike Ruben’s truck, the Jaguar could take care of itself. This left me with nothing to do but relive the horror of the last two days. Twenty miles outside of Santa Fe I had a panic attack and pulled into a restaurant parking lot. I couldn’t breathe and it felt like my heart was going to pound out of my chest. I was suddenly sure I was going to die and I was afraid and yet surprised that it even mattered to me. I took several deep breaths but it didn’t seem like I was getting any oxygen. I felt lightheaded and rolled the window down. I began to cry a little. I got out of the car and walked around the parking lot, huffing like a man that’s just run a marathon. I imagined that people were looking at me from their cars, that they knew what I had done. I took their offhand glances as accusations.

Forty minutes later I was pulling up to a Motel 6 outside of downtown Santa Fe. I paid for only one night. I didn’t know much about how the police tracked people, but I figured I had to stop using my credit card. I hoped that Julie could help me but I wasn’t sure what I was going to tell her. I walked to the gas station across the street and at the ATM I tried to take all the money out of my account. A message appeared on the screen telling me that I had a $300 per day limit.

With $300 dollars in my pocket I went back to my room and lay down on the bed. “At least I killed him,” I said. “You have to give me that.” But it didn’t make me feel any better. I was responsible for Anne’s death and the death of our child. If I’d just stayed away she would’ve been alive. The baby would’ve been alive. Had she never met me she would’ve still been alive. I didn’t think she would’ve believed her life with me had been worth the price she’d paid. Had she foreseen her fate at any moment during our time together she would have chosen another course. But, to me, knowing her now seemed worth every misery in my life, whether real or imaginary, past or yet to come. Despite the pain, which, alone in a darkened motel room, I thought--wished--would kill me, I would have suffered immeasurably more to have been her husband for one day, let alone the few short years we were married. At that moment, I would’ve gladly given my life just to hold her once more, to have one more conversation, to say three more words. “I am sorry.” Foolishly, terribly, I’d taken it all for granted. I thought of the night we’d been introduced at a party for a mutual friend who’d just won the Pulitzer Prize. I’d tried to impress her with the writers I knew, the places I’d been, the things I’d seen. She’d led me out on to the balcony where we were alone. I thought I had her. Then she told me that she didn’t care who I’d had lunch with or what beach I’d stood on, all that mattered was that she’d seen herself in me. She had me. It had all seemed so right then and now, in this place, I couldn’t imagine how it could’ve gone more wrong. However it had happened, though, I had done it.

I was almost asleep, which seemed the only mercy available to me, when my phone rang. It was Ruben. I looked at the clock. It was almost time for him to go to work. I didn’t answer; I just turned off the ringer.

Sixteen

I woke up at 5 AM, got dressed, and walked over to the 24 hour gas station on the other side of the parking lot. I bought a bottle of water, a small, overpriced box of Tylenol, and a peppermint patty. I went back to my room, washed a couple pills down with the water then ate the peppermint patty. I slept from about 5:45 to 10 AM then cleaned myself up, got dressed, and checked out. I didn’t know how I’d face Julie and I had no idea how I’d carry on a normal conversation, all I knew was that I had to; she had become my only hope. I suppose that somewhere inside I’d considered whether I might just take her down with me, but I didn’t think of that now. Instead, I got in the Jag and headed toward downtown Santa Fe. I had about a half hour to kill before Julie arrived, which was just what I wanted. I walked slowly through the streets trying to feel like I was on a planet with other people, like I had blood in my veins, like I was alive. I bought some coffee and forced everything about the last couple days back to the furthest reaches of my mind. It wouldn’t stay there long, I knew, but I might be able to pretend for awhile.

I was sitting on a bench in the plaza when I saw Julie coming toward me. She was smiling, walking quickly, and wearing an old sweater. It occurred to me that she was perhaps older than I’d initially thought.

“Hello,” she said, sitting down next to me.

“Hi,” I replied. Then I waited for the inevitable.

“How was your trip?”

I’d been preparing for this. My voice may have said, “Oh, it was okay. I was there for business. My agent’s office is there,” but I did not. I quickly asked her how the book club meeting had gone and she laughed.

“Oh, it was fine. We started out talking about the dangerousness of Captain Ahab’s obsession with the white whale and how it threatened the lives of the whole crew. Then someone said that all obsessions were dangerous and someone else wondered if the whale even existed and then it got too philosophical for me. I just want to read the book, you know?”

I told her that a story about fishing was just as valid as one about the perils of monomania. I’d long since given up trying to weave grand philosophy and sweeping metaphor into my own work. Any perceived symbolism or hidden meaning in anything I’d written was wholly the invention of the reader. I didn’t mind when this occurred—I was happy about it, of course—but it’s not why I wrote. Now I doubted that I’d ever write again. My own tale had become too tough an act to follow. “So, you remember seeing me at the mission?” I said, changing the subject.

She seemed a little embarrassed. “Yeah. And you remember me, don’t you?”

“Yes, I guess I do.” I tried to smile. “I waved at you at the coffee shop.”

“I know. I saw you. I thought you’d come in but I wasn’t sure if I wanted you to or not.”

“So you didn’t wave back.”

“So I didn’t wave back.” She pushed the sleeves up on her sweater. I expected her to continue, but she was quiet.

“That’s okay,” I finally said. “I wasn’t really sure if I wanted to come in or not either.” She gave me a look. I could almost feel her growing more distant. “I mean,” I continued, “I didn’t know if you were with that other guy or not.” She bit her lip and looked away. “I got your message. I take it you found him.”

She looked at the ground for a moment and said, “Yes, I found him.” Then she looked at me: “He’s my brother. He’s six years younger than me. I was concerned about him.”

“Did something happen?” I asked.

“No, he’s fine.”

“Just looking out for him then?”

“Something like that.” Suddenly she stood up. “Listen, I don’t really want to talk about this right now. I’m going to get some lunch. I’m starving. You’re welcome to join me if you don’t have anything else to do.”

I didn’t have anything else to do. “Yeah, I wouldn’t mind a bite,” I said, although I wasn’t in the least bit hungry. “What do you have in mind?”

We ate at a place called the Cowgirl Pick-up and I mostly answered her questions about San Francisco. It was an effort to talk casually about places like Golden Gate Park and North Beach, places that had suddenly become freighted with such terrible meaning, but I did the best I could. I asked her where she worked and she told me she helped operate a gallery on Canyon Road. She asked me where I lived in town and I told her I didn’t know.

“What does that mean?” she asked.

“It means that I’ve been staying in motels. I wanted the desert to permeate my writing so I’ve just been driving around out here.”

“Are you writing about the desert?”

“Not exactly.” I took a drink of my iced tea. “But Santa Fe seems like a good place to write--there’s so much art around--so I thought I’d stay awhile. You don’t know anybody with a room for rent, do you?”

She thought for a moment. “I might. Let me talk to someone.”

I paid the bill and told her it was a retainer for her finding me a place. She laughed and told me she had to go to work, but that if she found anything out she’d give me a call. Otherwise, she told me to stop by the gallery around 5 o’clock, when she would be closing up.

“It’s the Golden Horse Gallery, just before you get to Delgado.” (CONTINUED)

Alright, a couple things. First, I'm going to start posting two chapters at a time or this is just going to take forever. I like the idea of speeding things up and, of course, one of the lovely things about the internet is speed. However, with that comes a (further) reduction in editing. So, keep that in mind and if you notice problems with continuity, grammar, bad plot lines, etc. please let me know. I may or may not make revisions. So, that's that.

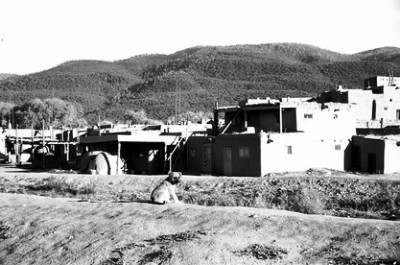

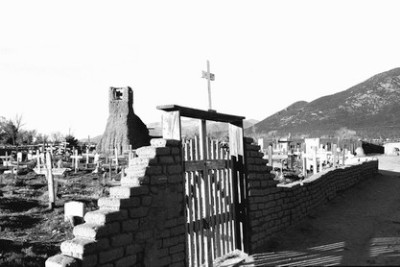

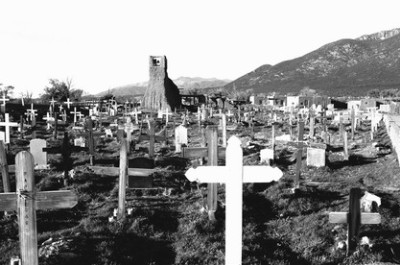

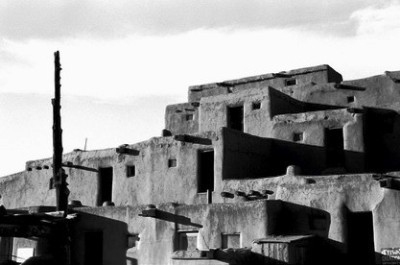

The photos from this post were all taken at Taos Pueblo, New Mexico. Taos Pueblo is the oldest continually inhabited community in North America. People have lived there for something over a thousand years. Crazy.

(CONTINUED) I turned the heat on low and forgot to watch the temp gauge so the truck overheated before 10 AM near the New Mexico line. I pulled well off the gravel shoulder to avoid the blowback of the semis. Once the steam had dissipated I looked under the hood. All the hoses appeared to be intact but the plastic reservoir was empty. I grabbed an old rag from the truck and eased the radiator cap off. A small cloud of hot steam billowed up into my face and then a steady trail of vapor rose from the pipe. I got back in the truck and sat looking out at the cloudless blue sky and the miles of rock and desert stretching in every direction. I couldn’t tell you what went through my mind although at some point I realized I was going to need water for the truck. Then the cell phone started to ring. It was Julie and I almost answered but an Arizona state trooper pulled up behind me and I turned the phone off and drew a long breath.

The trooper asked me what had happened. I told him the radiator had overheated and that I was waiting for it to cool. I didn’t know if Ruben kept proof of registration in the vehicle or not. If the trooper started asking questions I was going to find myself in trouble very quickly. Instead he asked me if I needed water and I told him I did. He went to his car and returned with a plastic jug. I got out of the truck and he asked me if I thought the water would get me to Lupton, where the next service station was. I replied that I believed it would if I kept the heater turned all the way up. He laughed and looked at the sky and said it wasn’t a good day to have the heat turned up. I laughed and said it was not and thanked him for the water. He waved as he pulled back onto the interstate and I poured water from the jug into the radiator.

I got back into the truck and checked the phone. Ruben had called while I was talking to the officer, but I didn’t listen to the message. I did listen to Julie’s message and she said that I could ignore her previous call about the boy but she still hoped to hear from me about the book club. She asked me to call her regardless of whether I could make the meeting or not.

With the heat back on full I was able to get all the way to Gallup before stopping. I got a couple jugs of coolant and a couple more jugs of water just in case. I ate at an old worn-out diner that had most certainly thrived a few decades earlier when Route 66 had brought travelers by the thousands right past its front door. Now, however, with the interstate bypass the management couldn’t afford to replace the cracked and scoured linoleum or the torn upholstery on the benches. Even the cups and dishes looked 40 years old. I ordered huevos rancheros and ate alongside the other patrons, Indians, mostly, and if the meal was good or bad I didn’t notice.

By 3 PM I was pulling into long term parking at the Albuquerque airport. For the last 100 miles the truck had been shaking and rattling so bad that it was hard to keep it going in a straight line. As I pulled into a spot I heard a grinding from the right front wheel. Now I knew I’d see the Jaguar again, but wondered if Ruben would ever see his truck. I walked a couple rows down and got into the Jaguar and sprayed the windshield to clean off the thin film of dust. I watched the wipers go back and forth until they started to squeak against the dry glass. I felt like I had to do something but it seemed hard to believe that there was anything that was worth doing. Then I called Julie McGregor and told her I was at Albuquerque International.

“You coming back to Santa Fe?” she asked.

“Yeah, I’m on my way.”

“Great. Can you meet with us next Tuesday?”

A plane flew low overhead and I had to wait a few seconds before replying. “Yeah, I can do that.” I didn’t know what else to say, so I asked, “Did you get everything straightened out with that guy you were looking for?”

There was a pause and then another plane flew over. Julie said something but I couldn’t make it out. “What’s that? I couldn’t hear you.”

She said that she didn’t want to get into it right then and that she’d tell me about it when I got into Santa Fe. Then she mentioned that she’d seen me watching her at the mission but the memory was painful to me now and I responded only in monosyllables. Finally, she asked me where I’d been.

“San Francisco,” I replied.

She told me she’d never been to San Francisco but that it looked wonderful and that she wanted to go some day. Then she began to ask questions about what I’d done and seen but I said that I’d tell her more when I saw her. She laughed and asked what I was doing that night but I was in no shape to see anyone so I said I was busy.

“That’s okay, maybe some other time.” But she sounded unsure so I said I was free the following day.

We agreed to meet in the plaza at noon and after she’d said goodbye I laid my head on the steering wheel. I felt far away from myself, unreal. Another plane rumbled overhead. I pressed my fingers against my aching eyes. All I had with me were the few things I’d left in the car. I drove out of the lot and merged onto northbound I-25. (CONTINUED)

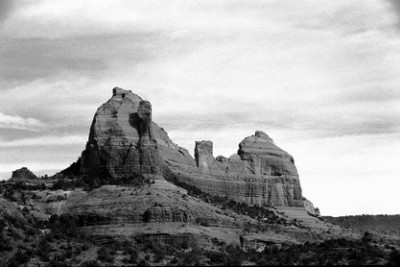

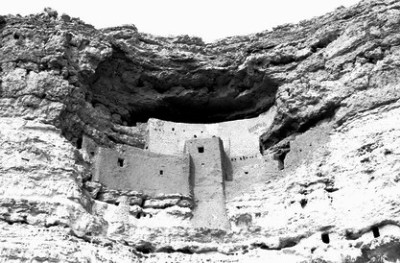

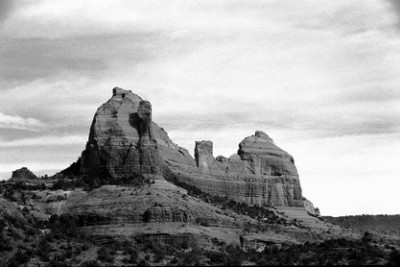

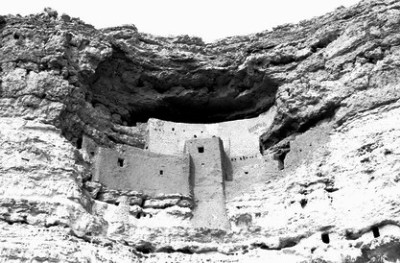

Photos taken at San Xavier del Bac Mission, Sedona, and Montezuma National Monument, respectively. That's all in Arizona.

(CONTINUED) It’s about 1200 miles from San Francisco to Santa Fe. I didn’t even know if Ruben’s truck would make it out of the city and that was the least of my problems. I felt like I was in a dream. It seemed as if nothing I did could possibly mean anything; action without consequence, life without meaning. I figured I had about eleven hours before Ruben would start wondering where I was and what had happened to his truck. By that time I’d be lucky to be in western Arizona if I wasn’t broken down somewhere in the California desert. That’s if I made it to the California desert. I realized that all my stuff was back at Ruben’s, but it hardly seemed to matter. I didn’t think of the police much. I thought mostly of Anne. My eyes stung and it was hard to keep them open. I was in big, big trouble.

I merged onto I-5 outside of Livermore and started toward Los Angeles. I could cut east on I-40 well north of the city, near Bakersfield, and then I had a straight shot through to Albuquerque. Ruben’s truck started to huff and clatter as I gave it some gas to get up to freeway speed. If I had to nurse the truck along at least I’d be forced to focus on something other than the horror that lay behind me and the horror that might lie ahead. But by the time I got it up to 70 it had smoothed out. I hit 72 and it started to buck and shudder, so I dropped back down to 70. Now I knew the trucks limits; my own had been exceeded past reckoning.

Traffic was light, at least for that stretch of road, and at some point my mind must’ve simply shut off, mercifully, like a circuit that’d been overloaded, because I don’t recall much until the signs for Bakersfield appeared west of Wasco and the sky was reddening as the sun sank toward the ocean. I thought I might no longer be nauseous but hungry. I cut east on 46 and picked up 99 south for a few miles before stopping at a Burger King. I put the plastic garbage bag in the dumpster outside and went in and washed my hands. Then I stood in line. Everyone looked worn-out and desperate; the customers, the employees, the manager in his white shirt, his belly spilling over the top of his pants. I could feel sweat on my forehead. No one made eye contact, even at the register; they looked at the menu overhead or the cracked floor or counted and recounted the coins in their hands. In a crowd of people on the edge I let myself believe that maybe I wasn’t the furthest out. It was unlikely.

I unwrapped my cheeseburger in the truck and ate a few bites. I chewed slowly and then opened the door and vomited into the parking lot. The woman in the next spot over didn’t even look at me. She just got into her car and drove away with her own problems. I closed the door and took a sip of coke. I ate a few fries. I started the truck and got back on the road. At Bakersfield I got on 58 which would take me past the air force base and at Barstow I picked up I-40. It was nearly dark and the Mojave splayed out before me, the mountains still just barely purple. Then night fell and the desert disappeared.

On the horizon I could see little red lights blinking atop invisible towers. The lights were my only reference points and when they’d be suddenly extinguished by the topography I could see nothing much beyond the strip of blacktop I was barreling down. I crossed the Arizona state line just east of Needles sometime after 10 PM. Outside of Flagstaff the truck bucked and groaned as the altitude began to increase. I pressed the gas pedal to the floor and the engine couldn’t suck enough oxygen to get the truck to accelerate. I’d had the heater on low since Oakland, when I’d first noticed the temp gauge creeping past the halfway mark. It had been fine since then, but now the gauge was climbing again as the grade steadily increased. I turned the blower to full and even with the windows down I began to sweat. The horror and fear that I’d struggled to keep at bay began to seep back into me and the dry heat and despair made me want to sleep. By the time I got to Flagstaff I could barely keep my eyes open. I pulled into a Motel 6 and heard the engine hiss and pop as soon as I turned the motor off. I opened the hood and felt the heat coming off the engine block. The temp gauge was over ¾ and it would take hours for the truck to cool down. I walked to the lobby and got a room. I had no choice.

I opened the door to my dingy, overpriced room and sat on the bed. It was 12:30 AM. Ruben would be calling in less than two hours. I turned my phone off and got into bed. I hoped Ruben would be able to find a way home. Then I cried myself to sleep like I hadn’t done since I was a boy. Strangely, in the morning my first thought was of a baseball championship my little league team had lost when I was a kid. I’d been inconsolable; it had seemed like the end of the world for me then, an entire season wasted. I opened my eyes and realized that now, all these years later, the world really had ended and I was living a wasted life in some new and terrible place.

I checked out before 7 AM and forced down a stale bagel and cream cheese from the hotel lobby. I checked my phone. Ruben had called six times between 2:15 and 5:00 AM. I didn’t listen to any of the messages. I did listen to the message Julie McGregor had left. She said that her book club was meeting in two weeks, on Tuesday, and that if I was going to be in town I should call her. Then I listened to her second message. She sounded upset and told me that she had seen me that day by the San Miguel Mission. Then she asked if I remembered the guy she’d been with and if I’d seen him since. She wanted me to call her either way. I put the phone in the glove compartment and started the truck. A horrible new world.

(CONTINUED)

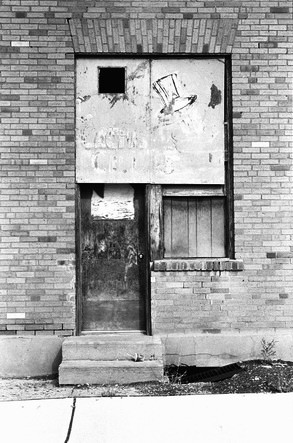

Photos taken at an auto salvage yard, Savage, MN, while on the hunt for brake calipers.