(CONTINUED) Twenty-Nine

I fell asleep for a few hours just before dawn and when I awoke the sun was well up but the house was quiet. I lay in bed and listened for awhile, but heard nothing, so I got up and put on some clothes and went downstairs. When I entered the kitchen I was surprised to see both Mary and Julie sitting silently at the table drinking coffee. I could feel the tension in the room. No one said anything as I went to the coffee pot and poured myself a cup. Then there was nothing to do but join them at the table. I pulled out a chair and as soon as I sat down I realized why no one was speaking; there were no words worth saying, nothing that could be easily expressed that would befit our situation. Silence was the only appropriate choice and so I drank my coffee and kept my own council and some of my thoughts were no doubt similar to those of the two women sitting next to me and some necessarily different; none were like any I had known until recently, even though I had written stories full of violence and pain, love and uncertainty, difficult decisions and death. But now that I finally knew the difference between literature and flesh-and-blood life I doubted whether many of the characters I’d created could’ve survived in the real world for very long. I began to wonder how much of myself was of my own creation and figured that the less that was down to me the better were my own odds of survival.

We each finished our coffee and then Mary finally said that we better get going and we all went out to the garage and Julie and I got in the Jag. Mary waited until I’d backed into the driveway and then she closed the garage door and got into the passenger seat. “Let’s go to First National Trust,” she said. “It’s down by the convention center.”

It was a busy Monday morning in downtown Santa Fe. Groups of pedestrians were gathered at the crosswalks and it took us longer than usual to get the few blocks from Canyon Road to W. Marcy Ave. I kept watching for anyone that might be following us, but there were a lot of cars on the road and it was difficult to keep track of them. We drove around the block a few times looking for an empty meter, then gave up and pulled into the municipal lot. I waited in the car while Mary and Julie went inside. I looked around and watched the cars and people and nothing seemed suspicious and everything seemed suspicious. I was driving a car with the wrong plates on it and shotguns in the trunk. I was a fugitive from justice and on my way to Tucson to try to rescue a drug addict from drug dealers. Sitting there in that parking lot, I started to feel nervous.

After a few minutes, Mary and Julie came out of the bank holding a canvas bag. They got back into the car and Mary told me to go to the Bank of America near the interstate exit. Again I watched my mirrors, keeping to the speed limit or slightly below. I didn’t notice anything. I waited in the car while they went into the bank. Ten minutes later they came back out with a bag.

We repeated this routine at five more banks. Nobody had an account at the last two—Mary and Julie just went inside and stood in the lobby—but we figured if we were being tailed it would appear like we were rounding up every last penny available. Including the gallery money, we had $31,094.00. Then we went to Julie’s apartment so she could pick up some clothes. I was afraid someone might have been to her place over the last two days--they might even still be there--so I went with Julie and Mary stayed in the car. But Julie said her apartment was just as she’d left it and if anyone had been in they hadn’t left the slightest trace. She checked her messages, but other than a couple calls from friends wanting to get a drink or dinner there was nothing. She quickly packed an overnight bag and we went back to the car. As we were heading back to Canyon Road I turned off Alameda and noticed a beige Land Rover slow behind me. In my rearview mirror I could see the driver, a man in his mid-thirties with two day’s worth of stubble, look at the Jag. He was wearing sunglasses, so I couldn’t follow his eyes, but it seemed like he had noticed something. However, he didn’t make the turn, but sped up again and continued straight ahead. We might’ve attracted his attention for several reasons and nothing good could come from most of them. I glanced at Julie and Mary but they were absorbed in their own thoughts and didn’t seem aware of much else.

We got back to Mary’s and I pulled the Jag into the garage. No one had eaten anything yet and Mary said she’d make us all brunch. I would just as soon have gotten on the road, but we needed something in our stomachs. Mary made us blueberry pancakes and put out a bowl of fruit. Julie only picked at her food but I told her she should eat and so she finished what was on her plate. Afterwards I packed a small bag, put the .50 caliber on top of my clothes, and strapped the 9 mm over my shoulder. Then I put on one of Dane’s suit coats that Mary had given me; Dane had been bigger than I and there was no visible bulge from the holster. The .38 was still in the living room where Julie had left it and I picked it up and put it in my bag with the .50 caliber. Then all three of us stood by the garage door for a couple minutes.

“We weren’t being followed, were we?” Julie finally asked. “Maybe we should just go to the police.”

I thought of that Land Rover but didn’t mention it. Instead, I said, “I think it might be risky.”

Mary nodded and Julie seemed about to cry again. “Then what are we going to do?” she asked.

“You’ll know what to do when you get there,” Mary replied. She seemed to mean it.

Mary and Julie embraced and then I thanked Mary and gave her a hug and she wished us luck and told us to call when we could, though she wouldn’t expect to hear from us until everything was over. Then she opened the garage door and Julie and I got in the Jag and drove back out into the cloudless blue noon and down Canyon Road. That payphone in Tucson was 600 miles away.

Thirty

We merged onto I-25 south out of Santa Fe and continued down to Albuquerque on the busiest stretch of road in the state of New Mexico. But it was the middle of the day and traffic was light. Julie looked out the window at the desert passing by--the dry gullies, blown-out trailer homes, and sprawling gas stations--but as we got closer to Albuquerque even the remnants of the desert gave way to strip malls and car dealerships. We made good time through the northern part of the city and picked up I-40 west. Soon Albuquerque was behind us and the desert reared up again as the buildings fell away. The sky loomed turquoise overhead, the sun flashed off semi trailers stacked fifteen and twenty deep in the next lane. We had yet to speak a word.

We’d been on the road for over two hours when I stopped in Sky City to get gas and something to drink. As I pulled off the highway, I noticed a beige Land Rover in the rearview mirror, but it continued west on the interstate. I could not be certain, but I thought it might be the same one I saw in Santa Fe. I began to suspect we were being followed. We wound down the frontage road, the suddenly bumper-to-bumper traffic creeping along. On the left was a massive gas station, the pumps and concrete apron spread out like an airport runway, a couple dozen semis parked along the far side. On the right was a casino, and a constant stream of RV’s and pick-up’s pulled in and out of the parking lot, which was separated from the road with orange pylons and presided over by an Indian directing vehicles with a pink flag. We had to wait in line to get to the pumps and I asked Julie if she wanted anything. She said that she’d come inside and I figured that was a good sign.

Finally, we got to a pump and I told Julie that I’d lost my credit card and she’d have to pay for the gas. In a way it was true; I’d cut my card up into little pieces back in Santa Fe. Somebody would’ve been watching for those numbers, I’d felt sure of that. Now I was almost out of cash. She gave me her card and went into the station. A couple minutes later I went in to buy a soda and two ice cream sandwiches. I didn’t see Julie inside and figured she was in the restroom. There was a copy of USA Today at the newspaper stand and I thought about picking it up, but didn’t. There was nothing I needed to know. I went back out to the car and waited for Julie. I’d finished my ice cream sandwich and was starting to get a little nervous when Julie finally came through the door of the station with a USA Today in her hand. She tossed the paper in the back seat before getting into the car. She had also purchased a bottle of water, but nothing else. I handed her the other ice cream sandwich, which was starting to melt a little. I was surprised when she took it and said, “Thank you”; I hadn’t really expected that she’d want it.

“I’ve always loved ice cream,” I said, as I pulled out of the gas station and turned back toward the interstate.

“Me too,” she replied. “There’s a place in Santa Fe that makes their own and they’ve got flavors I’ve never seen anywhere else, like sour apple and grape bubblegum.”

And so began an hour-long conversation on ice cream. We talked about our favorite flavors, the best ice cream shops we’d ever been to, and our cone preferences. We discussed consistency and sweetness, texture and cream content. When the conversation lagged we racked our brains to come up with details, no matter how trivial, to keep us talking and keep time moving. We were just west of Gallup when we dropped down a slight rise and I looked in the rearview mirror and saw the beige Land Rover at the top of the hill several cars back. Julie was telling me about some handmade ice cream she’d once had at a festival in Colorado when I interrupted her: “I think we’re being followed,” I said. She looked at me but didn’t turn around. “There’s a Land Rover a few cars back. I saw it in Santa Fe this morning and it passed us back at Sky City. Now it’s behind us again.”

“Are you sure it’s the same one?”

“No. But I don’t like the idea that someone might be tailing us. Who knows what they have in mind?”

A few minutes later we crossed the New Mexico state line. On the other side of the road was the spot where Ruben’s truck had broken down. A sign ahead indicated the turn-off for south U.S. Highway 191. I eased up the exit ramp and the Land Rover dropped back. As I crossed over the bridge that spanned the interstate I saw that the Rover had also exited and was following at a distance behind us. On the other side of the interstate 191 dropped away in front of us, straight as an arrow and nearly flat as a pancake. I didn’t see a single car in the twenty-five or thirty miles that was visible up ahead. “See that?” I said, pointing at the ribbon of empty highway in front of us. “That’s good. We can’t afford to get pulled-over.” I knew Julie was frightened, but she didn’t ask what I was going to do.

I waited until we were about five miles from the interstate then downshifted and pushed the accelerator to the floor. I could feel the Jag grab the road and in an instant Julie and I were pressed back in our seats. Behind us the Land Rover also began to gain speed. We were in the Painted Cliffs and the landscape was desolate, barren scrub desert on either side as far as the eye could see. Ahead of us, rangeland spread out to the south, broken only by rotten fences and battered windmills. In less than a minute we were doing over 120 mph and the Land Rover was falling behind. Julie gripped the dashboard in front of her and looked straight ahead. We blew past an empty concrete block tavern with Witch Well, AZ painted on the side in huge red letters. There wasn’t another building around that wasn’t in utter ruin, destroyed by the very land on which it was built. I could still see the Land Rover in the mirror and so I know he could see us. Then the road began to rise and fall a little and after a series of dips I could no longer see anything behind us. We could have picked up Highway 61 at St. John’s, but I decided to continue south, to the resort community of Eagar. There we could choose from any number of back roads and, even if the driver of the Rover didn’t decide to exit at 61, there was little chance he’d catch us. But I kept the pedal down all the way to St. John’s and then hit it again until we were into the mountains outside of Eagar.

It was not warm inside the car, but by the time we were clear of Eagar my shirt was wet and my eyes stung. The gun in its holster felt heavy against my side. Julie turned to look behind us and, since she didn’t say anything, I figured she didn’t see whoever had been back there. We started to climb higher into the mountains and the scenery was epic. Pine forests dropped away below us at every turn, revealing endless vistas of rock and tree and sun and sky. However, the road would no longer permit us to outrun even the slowest vehicle and I could only hope with everything in me that we wouldn’t have another run-in with the Land Rover.

Julie looked out her window, toward the slowly sinking sun in the west, and said, “They’re going to know about us now. That guy—whoever he was—is going to tell them what just happened.”

“I know,” I said. “But I don’t think we had much of a choice. We don’t know what that guy planned to do. Maybe run us off the road. Or follow us to our motel. Maybe he would’ve just shot us and taken the money as soon as he had a chance.”

Julie was quiet for a moment then said, “But if that’s the case, then we don’t stand a chance against these people. Jimmy might already be dead.”

“I don’t think so,” I replied. “We’ve still got the money.”

Julie turned from the window and looked at me. “No, we don’t. We have some money.”

She was right. Maybe we didn’t stand a chance.

We followed 191 as it wound its way through the Apache-Sitgreaves National Forest. We were not making good time and I began to expect the Land Rover around every turn, but as we neared Clifton we were still alone. I took a little detour at Clifton and picked up Highway 75 heading back toward the New Mexico border. It was early evening and I told Julie I didn’t want to get to I-10 before dark, when we’d have some cover from our pursuer, who might be scouring the highway for us at that very moment. Yet I was pretty sure I really only wanted to prolong our time in the Peloncillo Mountains, the saguaros creeping up every boulder-strewn mountainside, the tops of the peaks tinged with purple as darkness advanced, before we had to head toward Tucson. In the mountains it seemed impossible to believe that we could ever be in any danger greater than that nature had conjured all on her own, a landscape apparently hostile to every form of life, though it really was not. Out here some things did survive, and this gave me hope that Julie and Jimmy and I could too. Finally, the sky went blue-black and the sun sank behind the cactus-flecked mountains.

It was pitch dark when we doubled-back west on U.S. 70. At Safford we got gas, then dropped straight south on 191 and hit the interstate. Unless the Land Rover had pulled up right next to us, it seemed impossible that he could’ve identified us at night. I kept the Jag at 80 mph and, while I’d like to have gone faster, I didn’t dare risk it. It took us a little over an hour to get to Tucson and by then my adrenaline was gone and I was bleary-eyed and exhausted. We’d been on the road for over 11 hours.

We stopped at a motel just west of town, off the interstate. I guessed we were about fifteen minutes from the payphone. The motel sat at the end of a frontage road and it was ringed by a high fence topped with barbed wire. The bottom of the fence was covered with plastic bags and newspapers and anything else that could catch the desert wind. The parking lot was cut-off from all traffic but that destined for the motel. Julie and I walked into the lobby.

“How long have you guys been on the road?” asked the Mexican girl behind the front desk.

“That obvious?” I replied.

She smiled.

“Something over eleven hours,” I said, as Julie signed the credit card receipt. “At least I think so. I kinda lost track.”

She smiled again and handed Julie the room key and I went outside and pulled the car up in front of our door. There were pick-up trucks on either side of us and a number more scattered throughout the lot. Some of the plates were Mexican and I imagined that many of the people staying there were contractors, migrant workers, illegal aliens, anyone that needed to keep moving if they were going to survive. Like us.

We went into the room and I put the sack of money on a shelf in the closet and then tried to shut the closet door but it was off its rail and just hung from the ceiling so I let it go. I’d decided to leave the shotguns in the car. Julie put our other bags on the floor and then we each sat on a bed and while I wished I could just go to sleep I couldn’t tell whether I was dizzy from fatigue or hunger or fear or some combination. In any case, I didn’t feel well. Down the frontage road, within walking distance, was a restaurant. “I need to eat,” I told Julie. “And you should eat too.” She nodded and we got up and stepped outside. I locked the door and as we started walking my legs felt weak, like rubber. I realized my hands were shaking. I looked to see if Julie had noticed but she’d begun to cry. I put my arm around her and pulled her off to the side of the road. She began to cry harder. I held her. I began to shake harder. I wondered if this would be my last night alive. Suddenly car headlights hit us, huge and blinding. I pulled Julie close to me, believing it would be the Land Rover, but then a male voice yelled, “Get a room!” and there was laughter as the car went on and darkness settled back upon us. Julie looked at me and said, “But we’ve got a room.” She seemed so earnest that I laughed and she sniffed and smiled. I took her hand in mine and we continued on to the restaurant. (CONTINUED)

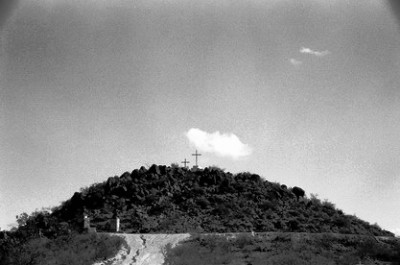

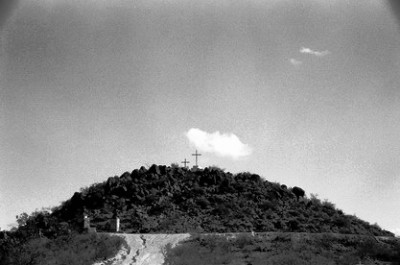

All photos were taken in the Painted Desert & Petrified Forest, Arizona, USA. And then there were two more posts.

(CONTINUED) Twenty-Seven

There was nothing to do except wait out the afternoon until it was time to pick up Mary from the gallery. Right then, time was one thing we didn’t need. We didn’t need time to think about what might be happening to Jimmy. We didn’t need time to think about what would be waiting for us in Arizona. And we didn’t need time to think about whether we’d ever make it back to Santa Fe. But we couldn’t think about anything else. Julie sat tearing at bits of Kleenex and I felt sorrier for her than I had for anyone in my whole life, with the stark exception of my murdered ex-wife; but that was different—that was my fault. I knew Julie was wondering what her life would be like without the most important thing in it—her brother. I thought that there was a good chance she’d never find out. I had to do something to occupy both our minds, so I dug around Mary’s house looking for a U.S. highway map. I managed to find a booklet that had the major roads in Utah, Colorado, New Mexico, and Arizona and I showed it to Julie.

“We’ll take I-25 to I-40 and then head into Arizona,” I said, and thought of the last time I’d driven I-40. It seemed like a long time ago; I wasn’t looking forward to driving it again. “In Flagstaff we’ll drop down to I-17.” I handed Julie the map, but it was ridiculous; we’d be following interstate all the way, first south, then west, and then south again. There was nothing to show or explain. Julie wasn’t listening anyway.

“Where do you think they have him?” she asked.

I shook my head. “There’s no way of knowing.”

“I wonder if they’re hurting him.” She began to cry. I put my arms around her and she leaned her head on my chest and wept. I thought of all the stories I’d read and the one’s that I’d written. I tried to recall every movie or poem or song that had ever meant anything to me. It all fell short of describing what I felt at that moment, a fire of emotions, good and bad, light and dark, all at a fever pitch. I saw that I couldn’t change whatever was to come and for that brief time I felt something unexplainable, inexpressible. But it had all come at a price that no sane person would willingly pay; now I only wished I could somehow cover the debt of the girl in my arms.

While Julie cried I thought about a story I’d written years earlier about a man, Orion, who set sail on a ship. Following an unspecified calamity--for one calamity is a good as another in such tales--he believed that he must leave behind everything he’d ever known in his life. It didn’t seem to him that it could much matter what he did after that. On the street he ran into a sea captain and, after talking for some time, the man mentioned to the captain that he was not sure what the next day would hold for him. “In that case,” said the sea captain, “why don’t you sign on with my crew?”

For many weeks the ship sailed from port to port, loading and unloading cargo, taking on passengers, and sometimes docking for days on the rotten outskirts of exotic cities. Soon Orion felt like he had never known a life previous, as if the salt and the surf, the flapping of the sails, and the calls of the hands as they moved about the deck had always been a part of him. It was not so much that he was happy, but forgetful, and in this forgetting was a peace that he had not known in some time. Each morning he woke with the sun to hear the creaking of timbers and the splashing of waves against the hull. Even far out on the ocean a company of seabirds always seemed to be near and he would watch them wheel around the masts. On some days dolphins would ride alongside, leaping in turn as they kept pace with the ship. He was learning the way of the sailors, assimilating their language and becoming more adept at their work. After a time, the sailors accepted him fully and soon he realized that there were others on the boat that had come aboard after him and that he was no longer the least experienced hand.

He became skilled at reading the weather, even in the dark of night, and the captain would come to ask his opinion of what might lay ahead. On such occasions he would look off to the horizon and consider the wind, as if it bore a message from a far-off and murky world. The clouds spoke to him and even in the most reckless tempests he would feel an otherworldly calm as the salt-sea swept over the bow and the gale lashed at him and his companions. Seeing Orion, the other sailors were becalmed and set about tying the sails and lashing freight to the deck with a certitude they would not otherwise have had. If it seemed odd to him that what had at first appeared to be the end of his life had instead brought him to a place where he felt a rightfulness he could not have imagined, he did not dwell upon it. He simply was and there was no need for anything other.

One morning Orion found himself in his bunk, chilled by the stillness all around. He left his cabin and went on deck. There were none of the usual calls amongst the men, not an order barked or a mistake roundly chastised. He was alone. The ship was rocking fore to aft, but did not seem to be moving. The sails lay unfurled and limp against the masts. The ship creaked and groaned with the rolling of the ocean. The sky was clear and though there was sunlight he could not place the sun above him. There wasn’t a bird above nor a fish beside the stranded vessel. He was seized with a terror so great that when he awoke he could not breathe and, lying there on his cot, he still felt a foreboding that would not leave.

As he climbed up to the deck the sun was just breaking over the horizon. The captain and some of the deck hands were standing along the bow, the sky lit in deep shades of red, a magenta strip of cloud just along the horizon. The very air seemed suffused in a rose light that was part mist and part fire. All the sailors turned as Orion approached but none said anything. He looked out across the sea, where thousands of miles away that crimson planet was rising quickly, as if to warn the men of their fate. Minutes past while Orion looked about, the men’s heads upturned as the heavens overhead seemed to lower onto them. The wind fell away and the blood red sky turned to black and yellow and green. Finally, the captain said, “It will be bad.” Orion nodded, but there was not much that could be done. Within minutes everything that could be battened down was secure, the sails taken in, and any loose items brought to the hold. Most of the men then stayed below deck, but the captain and Orion went back up to watch the slowly roiling sea and the churning clouds. Orion felt the hair go up on his arms. “I’ve never seen it so,” he said. The captain shook his head, “Nor I.” Soon the ship began to toss and the first waves crested the bow. Orion and the captain went below deck.

Normally the crew kept to their individual quarters when not above, but on this morning all hands were gathered together in the mess hall. The tables had been cleared of all cups and utensils but the ship began to pitch so badly that the men found it easier to sit on the floor. Some of the sailors were clearly frightened; others just as clearly were not. Under different circumstances, Orion would have found it interesting to consider why this might be, but instead he wondered how the great peace he had come to know so certainly had been so quickly imperiled. He’d grown to love the ocean and believed it would always be good to him. Even in the worst storms the thunder and lightning felt more like a benevolent promise than the threat of that which could not ever be fully reckoned. But now the creaking of the timbers grew deafening and from above the groaning of the masts could be heard. Each wave that crashed over the bow reverberated below deck with a sickening thud. Water could be heard coming down the steps from the deck. No one spoke.

The ship rose higher and higher and then dropped with the towering waves into a deep trough. A horrible cracking, like a tree being felled, boomed through the hold and the sound of wood snapping and splintering was followed by the rush of rain coming through the shattered deck into the aft hold. The captain staggered to his feet and steadied himself against a post. He struggled to remain upright and, in an effort to be heard above the tempest, roared, as if drunk:

“Said the mate of this vessel unique,

To the cap’n, ‘What port shall we seek?’

Said the cap’n, ‘We'll dock 'er,

In Davy Jones’ locker;

The bloomin’ old tub’s sprung a leak!’"

The men looked at their captain, and the captain looked at his men. He smiled. The first mate turned his head to see the other men and then, with some effort, stood. He boomed:

“There was an old sailor of Crete,

Whose peg legs propelled him quite neat.

‘Strong liquor," he said,

Never goes to my head,

And I know it can't go to my feet.’"

A few of the men began to laugh. A young sailor sitting cross-legged on the floor yelled:

“There was an old sailor of Compton,

Whose vessel a rock it once bump’d on;

The shock was so great,

That it damaged the pate,

Of that singular sailor of Compton.”

The crew laughed while the boat rocked and shuddered. Outside the wind howled and thunder cracked. The laughter of the men was swallowed up by the torrent pounding overhead. One of the oldest hands on the ship began to stand up but fell again after a wave pitched the boat sidewise. The men quieted in an instant, but the old-timer, now lying on the floor, began to laugh even before speaking. Several times he tried to get his breath and the men began to laugh just to see him. Finally, he caught his wind and sang at the top of his voice, in a reedy wail:

“A cabin boy on an old clipper,

Grew steadily flipper and flipper.

He plugged up his ass,

With fragments of glass,

And thus circumcised his old skipper.”

The men roared. Again the sound of wood snapping echoed from above. The sailors strewn over the floor clapped each other on the shoulder, tears in their eyes. The ship seemed as if it would burst apart. A voice trembling with fear and mirth and joy yelled over the din:

“There was a young sailor from Brighton

Who said to his girl, ‘You’re a tight one.’

She replied, ‘Pon my soul,

You're in the wrong hole;

There’s plenty of room in the right one.’"

Men clutched their stomachs and gasped. The captain fell back down to the floor, his face red and grotesque as he slapped at his knee. Suddenly the boat seemed to spin about in a complete circle and the men’s eyes grew wide and there was silence. Then all at once they exploded with laughter again, some pounding their fists against the very planks of the shuddering vessel. Orion joined them, thinking that if this was to be his death it was grander than he could’ve ever imagined.

It seemed to go on for hours; the storm’s fury matched by the sailor’s songs thrown again and again into its face, robbing it of its power. Finally the storm lessened and the men quieted and fell asleep where they lay on the wet planks of the mess floor. In the morning, Orion awoke early and went to the deck to survey the damage. The sky was blue and the sun, having just risen, shown softly down. A light breeze blew gently from the west. A gull cried overhead. There were large holes in the deck and the mizzenmast was gone. The mainmast was listing to one side and the rigging was twisted and torn. The captain was at the bow and Orion walked toward him. “I thought we were going to die,” Orion said. The captain nodded. “The funny thing was,” he continued. “After awhile I didn’t care.” He ran his fingers through his hair. “I wonder what you call it when you reach that point.” The captain kicked at a piece of wood on the deck and then looked to the east. He turned back to Orion. “Freedom,” he replied, and then laughed. “Congratulations, you’re a sailor.”

I wondered if I should tell the story to Julie; she was still leaning against my shoulder but her face was turned away from me. She had stopped crying but said nothing. I craned my neck around to see her better and realized she was asleep. I leaned gently back against the couch and closed my eyes. Mary wouldn’t be done at the gallery for a couple more hours.

Twenty-Eight

I let Julie sleep and I may have even dozed myself. When it was time for me to go to the gallery I tried to slide from under her but she woke and turned to look at me. I gave her a pat on the leg and told her I was going to get Mary. She didn’t say anything.

On the way to the gallery it occurred to me that it had been a couple of hours since I’d thought of the fact that my ex-wife had recently been shot right in front of me and that I’d beaten her killer unrecognizable with a fireplace poker. It was the longest I’d gone without playing through the scene in my mind since it had happened. As soon as I thought of it I wished I hadn’t; I wanted to save as much pain and guilt and anger as I could for Tucson, where it might get me through whatever was waiting.

I pulled the Jag in front of the gallery and looked around, wondering if there was someone out there watching. I hadn’t passed a single car on the way down and there’d been nobody behind me. Mary came out holding a cloth bag. She carefully locked up the gallery, got into the car, and put the bag on her lap. The bag was lumpy, stuffed full of bills. I turned the car around and headed back to the house.

“How is she?” Mary asked.

“Okay.” I said. “She slept for a couple hours this afternoon. She woke up just as I was leaving.”

Mary nodded and looked at me. “You’re really okay with this, aren’t you?”

“What do you mean?” I asked.

“I mean you’re ready to go down there with her.”

“Yes,” I said. “I am.” Mary started to say something but stopped. “I have no reason on earth not to help,” I continued. “I have nothing left to lose.”

Mary frowned. “I think if things go wrong you’re going to find that might not be true.” She turned and looked at me and almost smiled. “And if things don’t go wrong you’re going to know it’s not true.”

I wasn’t entirely sure what she meant, but I had a guess. I knew she was glad I was there.

We pulled up to the house and Mary told me to wait while she opened the garage door. There was an empty space next to her vehicle and she waved me in and then closed the door again.

“Do you think anyone is watching?” she asked.

“I don’t know,” I said. “I was wondering that myself.”

She went to a bench along the wall and returned with two screwdrivers. She handed one to me, then started removing the plates from her car. It was a smart move; I was a wanted man and the police were probably actively looking for my car. Exchanging my California plates for New Mexico ones at least provided some cover for interstate travel. I just had to make sure I didn’t get pulled over for something stupid; having Mary’s plates on my car wouldn’t play too well with the police either.

After we’d swapped the plates we went inside. Julie was sitting on the couch where I’d left her. Mary began to tell her about our plan to make it look like we were getting the money together the next morning but stopped when she saw the .38 in its holster on the table. “I guess you two have already talked about the plan.” Julie didn’t say anything so Mary got the two shotguns and handed them to me. “Put these in your trunk and don’t forget the boxes of ammunition. I’m going to start dinner.” On my way out to the garage I grabbed the Fed Ex envelope and put it in the car as well; there seemed to be no reason to leave it with Mary.

That night Mary cooked a feast. She made cornbread, stuffed peppers, chicken fajitas, and sopapillas. I set the table and poured wine. Mary called me over to the stove and quietly asked if Julie had needed the sedatives. I told her that she had not and that I was glad because we needed her to be alert and un-medicated in the morning. Mary nodded and went back to her pans.

I doubt that any of us felt like eating that night but we finished everything on the table. There wasn’t much left to say and the food kept the silence from feeling awkward. We lingered over the table all evening, asking for another tortilla or a little more wine. There was no pep talk that could be made that wouldn’t make our situation seem even direr, no plan to be got down by memory, no getaway that could be conceived of yet. But there was a strange comfort, an affection that came from fear and danger and longing and maybe something else besides. We were bound by bonds stronger than family, bonds formed and strengthened by the knowledge that one of us was not there and he was in trouble. Julie and I would either get Jimmy back or possibly lose our lives in the trying. Mary faced the danger of survival and what that would mean to her if we failed; it was a risk every bit as big as ours. But seated around that worn wooden table it seemed to make an almost mystical sort of sense.

We all helped to wash and dry the dishes, though Mary had a dishwasher, and then we each said goodnight and drifted off to our rooms. I took two sleeping tablets but awoke in the middle of the night, the desert moon high and bright, shining through my window. I looked at the clock: 3:04 AM. There was nothing I could do but lay awash in dread and doubt. I was a writer—or had been—and while I had at times considered myself tough, even imagined myself involved in the acts of savage violence I depicted, I was not a criminal or a gunfighter or a murderer. But I had become these things and, lying there in that bed in New Mexico, I no longer knew who I was or what else I might become. Could I become the kind of person that I would need to be to get Julie’s brother back and keep her safe? A year ago, a month ago, even two weeks ago, I could not have been that person. But now it seemed as if it might be possible. This thought was the only comfort to be found in that still and harrowing night. (CONTINUED)

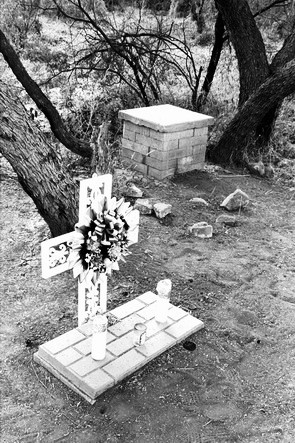

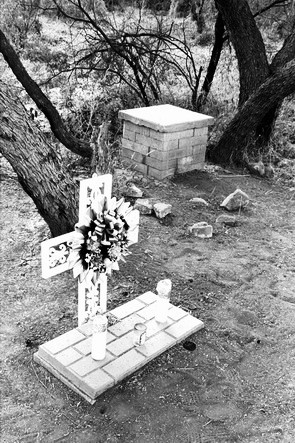

The top photo in this post was taken in the Petrified Forest, AZ. The second and third shots are from Courthouse Butte, Sedona, AZ. I'll wrap this up in three more posts. I promise.

(CONTINUED) Twenty-Five

I don’t know if Mary slept that night, but I didn’t. Mary had given Julie some prescription pills that should’ve knocked her out for at least eight hours, but when I saw Julie the next morning she looked worse than either Mary or I. She sat down in the dining room and put her head in her hands. Then she looked at Mary. She turned and looked at me and her face crumpled and she began to sob. Mary went back to the bathroom and returned with a pill bottle.

“If this keeps up, give her two of these.”

I took the bottle from Mary. If Julie and I were ever going to get Jimmy back, Julie had to get a hold of herself. As it was, she was in no state to travel, let alone confront what might await us in Arizona. I needed her to get the past the panic on her own, so I was going to do everything I could to make sure I wouldn’t have to use the pills.

Mary left for the gallery and I made Julie a cup of tea and found a box of tissues. The tea grew cold on the table as Julie cried. I asked her a few things about Jimmy--what she thought he might have done, who she thought might have him--but she would only shake her head in reply. Finally, she said, “You can’t come with me.”

“Why not?” I asked.

She sniffed and wiped her nose. “Because there’s no reason why you should.”

“So, you think you can do a better job on your own?”

She started to cry again, but more softly.

“It’s dangerous,” I continued. “Neither of us should be under any illusions about that. I think…”

“But that’s what I mean,” she interrupted. “There’s no reason for you to risk your life. You don’t know me. You don’t know Jimmy. You don’t know anything about us. And I don’t want you to do this.”

I watched Julie rub the tears from her cheeks with the palms of her hands. If she went to Tucson she would never come back. Nor would her brother. And she knew it. “Listen,” I said. “You’re not Captain Ahab asking your crew to sacrifice their lives for something that may exist only in your own mind. You’re right that I don’t know your brother, but I know he’s in trouble and I know he needs help. And I think I do know you.” She started to say something but I continued: “And I’m not going to let you go down there all by yourself. It’s suicide. You know that, don’t you?”

I didn’t expect her to answer and she didn’t. “Maybe we should call the police,” she said.

I thought about this for a few moments. “I don’t know,” I said, finally. “Maybe you’re right. They could be bluffing. But if they’re not, we’re putting Jimmy’s life in danger.” She started to cry again. “Why don’t we go through with the plan for tomorrow and see if we notice anyone following us.” She looked at me strangely. I’d forgotten that Mary and I had not told her about our meager plan.

Twenty-Six

By the time I’d shown Julie the .38 Special she’d be wearing she was sobbing and having difficulty catching her breath. I didn’t think she’d ever be able to use the gun, but there was no reason for her not to carry it. I tried to give her the weapon, but she wouldn’t take it. After a few minutes she’d calmed down and I put the gun in the holster and handed it to her again. “They’ll kill us,” she said. “If they see us with guns they’ll kill us.”

I hefted the 9 mm in my hand. “Maybe not.” I tried to smile. “We might kill them.”

She glared at me, angry and fearful. “I told you I don’t want you to come with me. You can’t be a hero. This isn’t like one of your books.”

“You’re right,” I said. “I can’t be a hero. A hero would be someone that had something to lose.” Then I added: “And there are no heroes in my books. You’d know that if you’d read any of them.” She watched me as I checked the safety lock on the Beretta. “I’ll tell you about my life when this is over,” I said. “But not now.” I wondered if that was true. Would I really tell her? Or did I just figure I’d never have to?

We went back out to the living room, the thick curtain still drawn. It was difficult to tell what time of day it was. We sat on the couch and I asked Julie to tell me anything about Jimmy that might help us--the type of people he associated with, the jobs he’d had, the trouble he’d been in--anything that might give us a clue as to what sort of people we were dealing with. But instead she started talking about when Jimmy was young and her father left and how she’d had to raise her brother by herself.

“I knew Jimmy was going to have a hard time even when he was a baby,” she began. “I was still a kid but I could just tell. I was glad…” She reached for a tissue and wiped her nose. “I was glad my father left before Jimmy had a chance to know him. Jimmy never would’ve made it even this far if my father had been around. I don’t feel any anger toward my dad. I guess I don’t feel anything, really, except gratitude that he went away when he did and never came back. My mother was never any use to Jimmy either. I felt sorry for her but I suppose I’ve always loved her. She embarrassed me. After my dad left she got even worse. I don’t know why. She should’ve felt free.”

I asked her if she’d wanted to raise Jimmy all along. She gave me an odd look that I couldn’t interpret then said, “Yes, I did. Like I said, I knew he was going to be in trouble--he just didn’t seem like he’d fit anywhere--and I thought because I recognized it I could help him. At first I was too young, but by the time I was 11 or so I took over from my mother. I knew there was nobody else that could do it. I tried as hard as I could.” She started to cry again. “And I know he’s tried, too. He’s fought with himself. But it’s like he was cursed.”

“It’s more than just being gay, isn’t it?” Again she looked at me strangely. “It’s not hard to tell,” I offered. “In my line of work it pretty much goes with the territory.”

She shook her head. “No, it’s not all because of that. It’s hardly that at all. Although I knew very early that he was gay. I think girls are better at picking up on that than boys are and, after all, I was his sister. That’s another reason I was glad my father wasn’t around. It would’ve been terrible for Jimmy. My father liked to fight.” She pushed her hair back and began to pick at a spot on the sofa. “I’m not sure if my mother even knows. If she does, she doesn’t say anything about it.”

“Can you tell me what Jimmy’s been into?” I asked again.

She reached for another tissue and dabbed at her eyes. Then she balled it in her fist and squeezed it. “I don’t know. He’s been into a lot of things. At first it was just stealing. Small things. From the grocery store or people’s yards. He didn’t do many drugs then. He drank a lot. He got caught stealing a car and spent some time in a juvenile hall. When he came home he started…” She paused for a moment and took a little breath. “He started working on the street. Going with older men, I guess. He was probably seventeen. Sometimes I didn’t even know where he was living. He really got into drugs around then.” She stopped and I thought she might start crying again, but she didn’t.

“What kind of drugs?” I asked.

“I don’t know. Almost anything, I think. Sometimes he was talking a mile-a-minute and other times he could barely keep his eyes open. I always knew when he was on something. When I saw needle marks on his arms I finally told him he had to do something or I’d call the police. It’s the only time I’ve ever threatened him. He agreed and went into treatment. While he was away I met my ex-husband, Steve, and when Jimmy came out we all lived together for awhile.”

“How did that go?”

She sighed. “Okay at first. Jimmy really seemed to be trying to stay clean. He got a job and paid Steve and I rent though we told him he didn’t have to. Steve was really good about it, too. I thought he might not want Jimmy around, but he was understanding and good to both me and Jimmy. But gradually he started to turn back to the street. He would be gone for days at a time and when he came home it was difficult to talk to him. Steve and I began to fight about what should be done. I wanted to do everything I could for Jimmy. I was his sister. Steve said that Jimmy didn’t want to be helped and I’d just have to face up to that. I knew he might be right, but I couldn’t live like that. I had to keep trying. Eventually Jimmy started stealing from us and one day he took Steve’s watch--it had been his grandfather’s. Jimmy wouldn’t admit to anything and they started fighting. Jimmy was no match for Steve. Steve broke Jimmy’s nose and left that night. We never got the watch back even though Jimmy tried. Or said he tried. I don’t know. Steve came home after a couple days, but it wasn’t the same. I knew if I didn’t forget about Jimmy it would only be a matter of time until Steve left for good. But I couldn’t forget that he’d hurt my brother. I was afraid he was beginning to remind me of my father.” She paused. “I can’t blame Steve for leaving. I think he believed Jimmy would drag us down with him.”

I couldn’t tell her that Steve had been right nor could I tell her that she’d loved her brother more than her husband. She probably already knew these things anyway. So I asked her if she kept in touch with Steve.

“No. I haven’t spoken to him in a couple years. I do think about him sometimes though. I hope he’s happy. I wish things could’ve been different.”

I didn’t bother to ask again about who she thought might have kidnapped her brother. She didn’t know. It was probably drugs. Whether small-time or something more serious I wasn’t sure. It didn’t really matter; either way it was bad. We knew they’d already hurt Jimmy. There was no reason to think they wouldn’t just as easily hurt us. I got up to make us some tea and as I waited for the water to boil I saw the Fed Ex envelope on the kitchen table, a piece of Jimmy’s finger stuck in a plastic baggie. Suddenly I felt sick to my stomach. (CONTINUED)

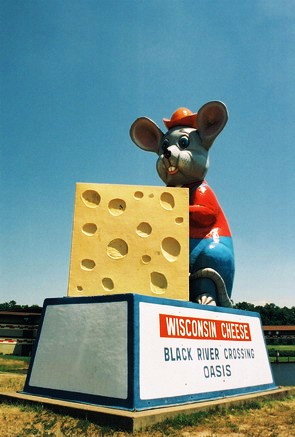

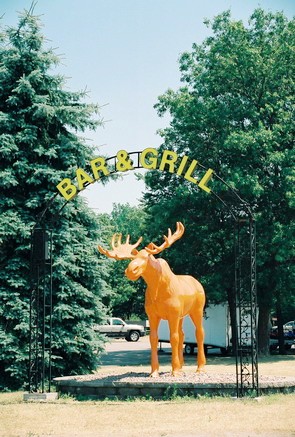

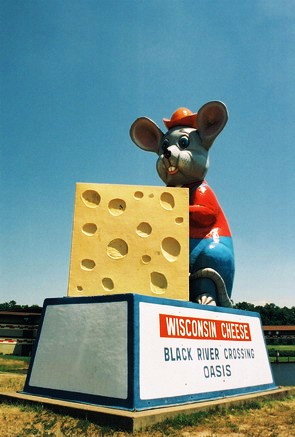

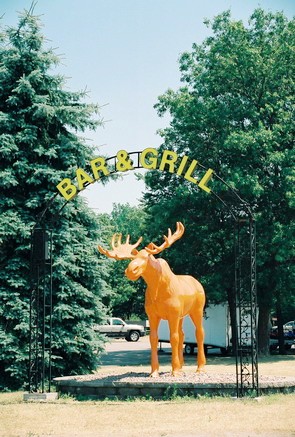

Nothing says fear and gun play better than the state of Wisconsin, and that's where these photos were taken. Four more episodes of A Loss for Words remain.

(CONTINUED) Twenty-Three

I woke in the morning and looked out the window at the perfect blue sky. I could see where Canyon Road wound down into town, every building soft-hued adobe, everything of a piece. I went downstairs just as the phone rang. It was Mary’s house, so I wasn’t about to answer. After four rings the answering machine clicked on and Julie said, “Tom, are you there? It’s Julie. I tried your cell but you didn’t answer. I thought maybe…”

I picked up. “Yeah, I’m here. I turned the ringer off on my phone.”

“So you won’t be disturbed?”

“Something like that,” I replied. “But don’t worry. I was just getting breakfast.”

“That’s good. I don’t want to be a pest. I just wanted to invite you to my brother’s birthday party tonight. It’s only going to be Jimmy and Mary and me. And you, if you want to go.”

To be honest, after what Mary had told me, I wasn’t sure I wanted to meet Julie’s brother. I had enough trouble of my own. On the other hand, I was curious. Curiosity won. “Sure,” I said. “What time?”

“You can stop by the gallery around closing. We’ll leave from here.”

“Okay. See you then.”

I had some cereal then walked back down to the newsstand. There was nothing in the SF Examiner or USA Today. I walked back to the house and turned on the TV and watched half of an old John Wayne movie before falling asleep. When I woke it was two in the afternoon. I pulled a copy of Cormac McCarthy’s “Blood Meridian” off the bookshelf but I had a headache and only got six pages in before I went upstairs to look for some aspirin. I wondered what sort of evening it was going to be.

I left the house a little after four and got to the gallery early. Julie was with a customer so I went looking for Mary. I found her in the stockroom, checking things off a sheet of paper on a clipboard.

“So, looking forward to the birthday bash tonight?” I asked.

She didn’t look up. “I’m not going.” She made another mark on the paper and bent down to pull the bubble wrap back from a painting. Something was wrong.

“You want to stay away from Jimmy?”

She stood up and took off her glasses; they hung around her neck by a chain. She looked at me. “No, that’s not it. And that’s all I’m going to say.” Something was very wrong.

I walked back out to the gallery floor and waited for Julie to finish with her customer. I watched her carefully wrap a small statue and a painting. The man paid in cash, which I thought was unusual, but after he’d left Julie told me it was pretty common. “I’m not really sure why they don’t just use a credit card,” she said. “But that’s $5,500, just like that.” She spun the tumbler on the safe next to the desk. I looked away, wondering if she’d consider me a security risk.

“Mary’s not going to dinner?”

Julie put the money in the safe, closed the door, and spun the tumbler. “Yeah, I guess she’s not feeling well.”

I nodded. I was concerned.

Julie and I left a little before 5—Mary said she’d close up—and we walked up Canyon Road to The Compound, where we’d be meeting Jimmy. We went inside and sat down and waited. Julie talked about some of the new pieces that had come into the gallery and asked how my writing was going, but every few moments she’d glance toward the door, searching for her brother.

At 5:20 Jimmy came in and sat down. “Sorry I’m late,” he said. He and Julie embraced and she introduced me. I stood up and took his hand. It was cold and limp. He had a slight lisp. I hadn’t seen him since that day out in front of the Pink Adobe. I thought he seemed different. But I guessed everything seemed different to me now; that day seemed a lifetime ago. Still, he was pale and thin and there were dark purple rings under his eyes. He looked like he needed sleep. Maybe he was staying awake because of drugs or fear or homelessness. If I’d had to guess I would’ve gone with all of the above.

We ordered our food and Julie asked her brother how things were going and whether he’d found a new job. She wanted to know if he’d found a different apartment. She asked each question off-handedly, without urgency, as if she were merely curious. Yet her eyes searched her brother carefully, looking for clues, as she waited for him to answer. Jimmy picked at a piece of bread and mumbled noncommittal replies. He barely looked up. I knew that what Mary had told me had been true; he was in trouble. Our entrees came and Jimmy had taken no more than three bites when his cell phone rang. He excused himself and went back toward the restroom. Julie cut her eyes at me, but didn’t say anything. In a few moments he returned. Whereas before he’d looked tired and wasted, he now looked scared and upset. He didn’t sit back down.

“Man, I’m really sorry. I gotta go.”

If Julie was angry she didn’t show it.

“Why, Jimmy?”

“I forgot I had to meet some people.”

“Can’t it wait?”

“Nah. We’ve got some work to do.”

Julie started to say something but Jimmy stopped her. He was pleading: “I’m sorry, sis. I gotta go.”

Julie sighed. “Do you want to take your dinner?”

Jimmy was already walking away. “Box it up for me, will ya? I’ll stop by and get it tomorrow.” He waved at me. “Nice to meet you.” I waved back.

A few minutes after Jimmy had left I noticed a scruffy, unshaven man come into the restaurant. He looked around and then left. Julie didn’t see him. Nor did she say much after Jimmy left. I finished my meal and thought about things. I’d recognized something of myself in Julie’s brother. That’s how I knew he was in trouble.

After dinner I walked Julie to her apartment on the other side of the plaza. The sky was clear and the stars were spread out above the city. Julie apologized for her brother and I told her not to worry about it. The night air was cool and there was no wind. We stopped outside her complex but neither of us said anything. I took her hand in mine and she drew toward me. We kissed and pulled each other closer. Then we broke off and stepped back.

Some believe that desperation incites passion, that danger impels the heart to respond more strongly, that sorrow longs for human touch. But these things are not always true. Fear and pain do not bring people closer; they pull them apart. Desire can be replaced by paranoia. Love by separation. We cared too much to pretend.

“Are you going to make it to the book club this Tuesday?” she asked.

I kicked at the ground. I looked down the street. “I don’t know. I might have to leave town for a bit.”

She didn’t ask any questions, she only nodded and glanced up at the big yellow moon. Then she looked away. “Good night,” she said.

“Good night,” I replied.

Twenty-Four

On Saturday morning, one week after my ex-wife had died in my arms and I’d beaten her killer to death, I had my things in the Jaguar before ten o’clock. I got in the car and drove down through the plaza and out to the interstate. I didn’t know where I was going. Then I turned around and went back to Mary’s. I made myself a sandwich and waited for her to return. I was reading Faulkner when she got in. I put the book back and stood up.

“Hello,” I said.

“Hi,” she replied, setting several large packages--probably paintings--wrapped in butcher’s paper down in the hallway.

“I want to thank you for everything,” I continued. “But I think I’m going to be on my way.” I asked her how much I owed her and reached for my billfold; I hardly had any cash left. She waved her hand and told me she didn’t want my money. I wondered why I’d come back. Had I really wanted to get caught? I took a step toward the door.

“I want the truth,” she said.

I stopped and looked at her.

“I know who you are and I want you to tell me what happened.” She didn’t seem scared or nervous. She just seemed angry. “I think I’ve come to know you over the last few days and if I really thought you posed a threat to me or that girl”—she pointed toward the front door—“or anyone else the police would already be here.” She took a step toward me and put her hands on her hips. “I deserve the truth for helping you.” For a moment I considered the situation.

“Okay, I’ll tell you.” I finally replied. “But, in return, I want you to write a letter that contains every word I say and send it to someone. I’ll give you the address.”

We went into the dining room and sat at the table. I told her the entire story from the day I’d left Santa Fe until the day I’d returned. When I was done she took off her glasses and rubbed her eyes, then shook her head.

“I knew you were in some kind of trouble right away, but I never figured it was that bad until I saw the newspaper. Are you telling me the truth?”

“If I wasn’t would I say so?”

She nodded. “I meant what I said about knowing you. And I’m sorry. Truly. Where are you going to go?”

“I don’t know.” I took a pen off the table and picked up a napkin. “But I want you to send a letter to Anne’s mother. Tell her what I told you.” I had just handed her the napkin with Beverly Michael’s address on it when there was a loud knock at the door. I was out of my chair in an instant.

“Quick,” Mary said. “Go out the back.”

I’d taken two steps through the kitchen when I heard the front door open. I turned and saw Julie pass through the hallway and run into the dining room. She was holding something in her hand. Mary went to her and Julie collapsed in her arms, crying and shaking. “They’ve got him,” she sobbed. “They’re going to kill him.” I took the Federal Express envelope from her hand and looked inside. In a plastic bag was what appeared to be the tip of a pinky finger cut just below the third knuckle. There were also three Polaroid photos. The first was of a right hand tied to a plank with two pieces of rope, the fingers spread wide. The second was of the same scene, only now the tip of the finger was severed and blood had pooled around the hand. The final shot was of Jimmy’s face; I didn’t know whether it had been taken before or after his finger had been cut-off, but I hoped it had been after; I didn’t want to think that he might look even worse now.

“Is that all there was in the envelope?” I asked.

Julie shook her head and handed me a crumpled note that she’d been clutching in her fist. It said that they wanted $100,000 or they’d kill Jimmy. It said they would provide more information at noon on Tuesday, when they would call a payphone in Tucson. If no one was there to get the call, Jimmy would be killed. It said that if any move was made to bring in the police they’d know and kill Jimmy immediately. Then I gave it to Mary to read.

“Do you think they’d really know?” she asked. “Do you think they’re watching us?”

I walked to the living room window and looked outside. I didn’t see anyone. Still, it was possible. I went back to the dining room.

Julie wiped her eyes and asked if we should call the police. I looked at Mary but she shook her head slightly.

“We better act like someone’s watching.”

They’d given Julie until Tuesday so she’d have time to get to the bank and make it down to Tucson. They would probably want her to come alone, but they hadn’t said anything in the note. So, I would go too. Anyway, I wasn’t a cop.

“How much money can we put our hands on?” I asked.

Mary shrugged. “Most of the gallery money is tied up in our floor stock. I’ve got $20,000 in savings and $10,000 in the safe after yesterday’s sale.” Julie had $5,000. I had nothing except an expensive sports car that would get me arrested if I tried to sell it.

“We’ve got to make it look like we’re getting money before Julie and I go to Tucson. It has to look legit…”

Julie looked at me and started crying again and Mary went to the bathroom to look for a sedative. I went around the house and closed all the blinds and curtains.

Mary led Julie to a second guest room on the first floor and then she and I began to come up with a plan. The next morning she’d go to the gallery as usual and I’d stay with Julie. Before leaving in the evening she’d get all the money out of the safe and put it in a sack. I’d drive down to meet her and bring her back to the house so she wouldn’t have to walk up Canyon Road with $10,000 in cash in a bag. On Monday we’d get up and go to the banks and Mary and Julie would withdraw most of their money. All together, we’d probably just break $30,000, but if someone was watching us we figured they’d have no way of knowing how much money we were really getting together. Then, in the afternoon, Julie and I would leave for Arizona. And that was as far as our plan went. Because we had to wait for instructions in Tucson it was impossible to guess at what might come after that phone call. If they wanted us to leave the money at a drop point, only releasing Jimmy after all the money was counted, we’d have a problem. Not only did we have nowhere near the amount demanded, we had no guarantee they wouldn’t just kill Jimmy anyway. Instead, barring a long-shot meeting in a public place, they’d probably want us to go to some old warehouse or derelict building. Normally, this would be the most dangerous of scenarios, but in our case it might be the only way of getting Julie’s brother back.

I asked Mary what would happen if we lost her money. There was a chance we’d find ourselves in a situation where all we could do was offer what little we had; they might accept it. Or they might take it and kill Jimmy. Or they might take it and kill all of us. No matter what happened, it wasn’t likely Mary would see her money again.

“Don’t think twice about the money,” Mary replied. “It’s only paper. Dane left me a lot more that I’ve got tied up in the gallery. Just do whatever seems best at the time.”

She told me to follow her down the hall and we went into a small office. There was a large oak desk with a computer on top of it. Papers were scattered here and there and a leather sofa took up one wall.

“This was my husband’s den,” Mary explained. “I use it as an office now, but I can still picture Dane napping on that sofa. He used to smoke cigars when he worked in here. Can you smell them?” I could. Then she opened the closet. Inside was a gun safe. Mary turned the tumbler back and forth and opened the door. Over her shoulder I could see three or four shotguns. Boxes of ammunition lined a shelf at the top. She handed me a Winchester 12 gauge and a Remington 32. From a locked box at the bottom of the safe she took a Desert Eagle .50 caliber handgun, a 9 mm Beretta pistol, and a Colt snub-nosed .38 Special. She ejected the chamber on the .38 and loaded the rounds. Then she closed the chamber and gave it a spin.

“We’ll give this one to Julie. I don’t know if she’s even held a gun before.”

“You don’t know if I have either,” I said, cracking the stock on the Remington.

Mary slipped a magazine into the Beretta. “And I don’t want to know.”

We loaded the other weapons and I asked Mary if her husband had ever seen combat. “Yes,” she replied, “in Korea. Most people don’t think much about Korea and I don’t really know what went on there myself. Dane didn’t ever say much about it, but I can tell you that it did something to him. It took something from him and gave him something else entirely in return. I don’t think he always knew what to do with that something else.” She handed me a box of shotgun shells. “So sometimes he just went hunting.”

Mary put the .38 and the 9 mm in holsters. She put the .50 caliber in a canvas bag and slipped the shotguns into cases. “We’ll put your car in the garage tomorrow night and transfer the guns then. There‘re no windows in the garage so there’s no way anybody will be able to see what we’re doing in there.” She put her hand on my shoulder. “I knew she was in trouble. And I knew you could help.”

I didn’t remind her that I was in trouble, too. But now I knew why I’d come back. (CONTINUED)

The top two photos were taken in Clayton, NM, USA. The bottom shot is from Montezuma, KS, at the Gray County Wind Farm, somewhere off US Highway 56. By the way, I've totally lost track of what photos I've already put up. Let me know if something looks familiar. Or, on second thought, maybe you shouldn't.

In other news, City of Dust just passed 100 posts and 10,000 site visits. Such are the rewards of blind--and possibly unwarranted--tenacity! If you're wondering just how much longer this A Loss for Words thing is gonna go on, I can now give you an answer: 5 more posts. Whew.

(CONTINUED) Twenty-One

I spent most of the next day in my room, looking out the window or lying on the bed, trying to guess how long I could live this way. One minute I would think I could keep it up indefinitely, as long as the police didn’t find me. The next minute I would be plunged into despair so profound I’d consider calling the cops myself. In the late afternoon I went for a walk through town. I almost stopped by the gallery, but Julie and I had made no plans and our parting the night before had been unsatisfying so I decided to leave her alone.

When I got back to the house Mary was already home. I heard quick footsteps upstairs as I came in the front door and then silence. I wondered if she’d been reading the Chekhov story. I sat down by the piano in the living room and leafed through a first edition of Lolita. I’d never even seen one before; it was probably worth $2,000.

In a few minutes Mary came downstairs and asked me to have dinner with her again. I had no reason to refuse, so I asked her if she needed any help. She told me to just sit tight and relax. Then she laughed: “But be careful with the first editions.”

Soon I could smell garlic and onions and chicken. Fajitas. I wondered if my face was being shown on television back in San Francisco: “Wanted in connection with a brutal double homocide.” And my unborn child could be counted as a third murder. Would the story go national? I made a note to pick up some out-of-town newspapers the next day. I considered whether I might have to start running again and I didn’t know if I had it in me. Finally, Mary called me out to the dining room.

I sat down in front of nearly a dozen small bowls and plates. Cheese, beans, peppers, carrots, sour cream, guacamole, pico de gallo, beans. I didn’t know whether Mary’s generosity was driven by kindness or loneliness. I told her that the food looked delicious and thanked her for the effort. She smiled slightly and nodded, then spooned some beans onto a tortilla and handed the plate to me. In contrast to the day before, she seemed quieter, more reflective. I imagined that she was watching me, looking for clues one way or the other, her strange new boarder making her more and more curious. We ate in silence until Mary said, “Julie told me I was right.”

I scooped a dollop of sour cream onto my food and said, “Excuse me?”

“I told her you were divorced. She said I was right.”

I took a bite and chewed slowly. Once again we were heading into dangerous territory.

“How’d you know?”

“Oh, a person can tell when a man has been close to a woman for a long time. There’s something about the way he carries himself, something in his face and in his eyes. It’s a kind of seriousness; an intensity, maybe. Anyway, I can tell. Maybe that’s because I was married to Dane for 42 years and I could see it in him.” We both grabbed for bowls and spoons, heaping lettuce and tomato onto our plates. “But it didn’t take 42 years to see how being with me changed him. I think I noticed it sometime in the fifth year we’d been living together.”

“Then, is this thing you see—is it a good thing?”

Mary frowned. “Well, yes and no. I think there’s good in it—tenderness and patience and a real appreciation of what it means to love another person. A knowing. But there’s also pain and self-doubt and the resentment that can come from dreams deferred.”

“But you and your husband never divorced,” I said.

“That’s true. But it doesn’t matter. Staying married is hard work. It can be more painful than separating, which is why people break-up.”

We both went back to our fajitas, eating in silence. When we were finished Mary asked me if I’d like some Mexican coffee. I said I would and she made us two cups and came back to the table. She blew across the top of her cup and a little swirl of steam rose up and died away. I sat back and waited for mine to cool a bit.

“Julie said she had a nice time last night. She’s been talking about you a lot around the gallery.”

I laughed and reached for my cup. “I’ve gathered that a few words have been exchanged between you two.”

Mary didn’t laugh or even smile. She looked at me over the top of her cup and said, “Did she tell you about her family?”

“Yeah,” I said. “She told me her mom still lives in town and that her father left when she was young. She also said she has a younger brother.”

Mary nodded. “Is that all she said?”

“Yeah, pretty much.”

She sipped at her coffee again and I watched her uneasily. “I know you two have secrets” she said. “We all do. It can’t be helped. I don’t know what yours are, but I do know some of hers. I’m going to tell you a few of them and the only reason is because I think you’re both in trouble. I’ve thought about this a lot over the last two days and neither of you is going to get very far the way you’re going. By that, I mean I think someone is going to get hurt. Romantically, I don’t know. That’s not my place. But I do believe you can help each other and if I have to put my nose where it doesn’t belong for it to happen, I’m willing to do it. But, before I go on, let me ask you, how do you feel about her? If I’ve read things wrong then I don’t want to tell you anything that might put her in a compromising position. So, please, just be straight.”

I ran my middle finger along the lip of my cup and watched the surface of the oily black coffee ripple. I didn’t really know what to tell her, so I said, “I think I see something—recognize something. But I’m not certain yet. I could be wrong.”

She nodded. “I don’t think you’re wrong. I think you just need more time and I’m not sure you have it.” I turned to Mary suddenly, wide-eyed. She was on to me, I was sure. She’d read something or seen something or done some investigating. I began to speak, but she stopped me. “Don’t worry. She’s not sick or anything. It’s just that certain things need to be dealt with.” I leaned back in my chair. I could feel my heart beating. I had no idea where this was going. “Let me go back a bit. Julie’s father did leave when she was very young. I remember it well. It made the papers here in Santa Fe. Her father—Edmund was his name—was a judge. He was a mean, unfair man with a wicked temper. He was often drunk on the bench and who knows how many innocent people went to prison because of him. Or how many guilty people went free. Julie has told me that he would beat her and her mother terribly. Just after her brother was born Edmund was arrested at a brothel up in the mountains, out near Socorro. Edmund was disgraced and left town one day without a word. It should’ve been the best thing that had ever happened to that family, except that Julie’s mother couldn’t handle keeping up the household anymore. She wouldn’t go outside either, because she thought people were staring at her.” Mary paused and drank from her cup. “And I suppose some people were staring at her. Anyway, she started to get a little funny and that meant that Julie had to raise her brother. She tried to do everything for him—cooking, helping him with his homework—but he started getting into trouble very early. There were fights and drugs and arrests by the time he was in junior high. At some point Jimmy—that’s his name—started living on the streets. Hustling, I guess you’d call it. Drug dealing. Petty theft. Soliciting. It broke Julie’s heart to see her brother destroying himself, but there was nothing she could do. He wouldn’t listen and he wouldn’t accept any help, not even from his own sister.”

Mary stopped for a moment. “You know,’ I said. “I’ve seen them together. They seemed to be getting along okay.”

Mary nodded. “Julie told me about that. You see, they do get along. Jimmy would do anything for Julie. The only thing he won’t do is let her help him.”

“Julie did call me several days ago, looking for him. That was a little odd.”

“Yes, this is where the real trouble starts. Julie thinks that Jimmy has really gotten himself into trouble. She doesn’t know whether it’s drugs or stealing or what, but she says that he’s scared, even though she tells him everything’s fine.”

“And you think she’s right.”

Mary took our empty cups and walked them to the sink. “I’m sure she’s right. I overheard him talking to a man in the plaza one day. I couldn’t make out everything, but I heard this man tell Jimmy there would be trouble for him and Julie if something wasn’t fixed. I don’t know what this ‘something’ is though.”

My desert oasis had vanished. I’d known that I hadn’t deserved what I’d found in Santa Fe. Now everything had changed in an instant. I let out a long breath as Mary returned to the table.

“I just wanted you to know this. Julie is very frightened for Jimmy. If anything happens to him her world will collapse.”

“I’m not sure what I can do,” I said.

She leaned forward, her elbows on the table. “I want you to think of something.” It sounded like a threat. I wondered again how much she might know about me. The she softened: “So now you know. Anyway, how’s the writing been going?”

That night, lying awake in bed, I thought about secrets and lies. The things we say and, more importantly, the things we don’t. Now I knew that I had recognized something in Julie. I also knew that I no longer had any power over it.

Twenty-Two

The next day was Thursday and after Mary had left I walked down to the international newsstand. I bought a day-old San Francisco Examiner and a USA Today. I got a cup of coffee and a croissant from a café and found a bench in the plaza. After I’d finished eating I sat there for a long time, drinking the coffee, the papers folded next to me. I looked at my phone messages, deleting two more voicemails from my agent and a few from old friends that I knew couldn’t help me. I saved three from Ruben but didn’t listen to them. The last call was from Anne’s mother—I didn’t even think she’d had my number—and I knew I’d have to listen to it. But first I picked up the SF Examiner and flipped through to the Metro section. It had been nearly a week since Anne’s murder and, unless there’d been some new development, I doubted that they’d still be following the story closely enough for a feature. I hoped there wouldn’t even be a mention, but there was, toward the back of the section:

“Bay Area law enforcement officials are continuing their requests for the public’s help in finding the chief suspect in last Saturday’s double homicide. Anne Gould and her boyfriend, Steven Foster, were found dead in Ms. Gould’s Walnut Creek home on Sunday morning, after Ms. Gould failed to attend a family function. Police officials have called the murders ‘brutal and cold-blooded’ and are looking for Ms. Gould’s ex-husband, Thomas Gould. Gould, author of the best-selling novel, “Cries from the River,” has not been seen since the day of the killings and police are asking anyone with information on Gould’s whereabouts to immediately contact the Walnut Creek Police Department. Mr. Gould should not be approached as he is considered armed and dangerous.”

There was a small picture of me accompanying the piece but it was grainy and several years old. The photos they’d used for the TV coverage had probably been better. I now knew that Ruben had told the police he’d seen me--he couldn’t have said much more--but I hadn’t learned anything else. There was no mention that Anne had been pregnant and no description of the murders themselves. I had some hope that Anne’s death would be linked to Steve Foster through his gun but there was no indication that it had been. I figured that more information would’ve been included in the stories earlier in the week. I picked up the USA Today and leafed through it, but found nothing. It was small comfort.

Waves of fear came over me and I sat on the bench waiting for them to subside but they didn’t. I was not famous, but I was known and someone, somewhere who’d heard about the killings would eventually recognize me. For awhile I once again considered turning myself in. More than anything I wanted to be cleared of Anne’s murder--I could confess to killing Steve Foster--but I had no confidence that the truth would be accepted. And even if it was, I didn’t want to go to jail for Foster’s murder. When I thought of his body lying on the carpet, nearly headless, I knew that I wouldn’t be contacting the police.

I picked up my phone and listened to the message from Anne’s mother: “Thomas, this is Beverly Michaels. I don’t know if you’re checking this phone but I want to say…” Her voice broke and there was a long pause. “…I want to say that I don’t think you killed Anne. The police say they aren’t sure, but I am.” There was another pause. She sounded sad and exhausted, utterly and finally defeated. “I want to ask you to contact me somehow and tell me what happened. I don’t care how you do it. Please do me that dignity. I need to know.” She sniffed. I wondered if she knew Anne had been carrying my child. “Tell me she didn’t suffer.” There was some rustling and then the line clicked off.

I had never gotten along with my former mother-in-law. She was a proud, vindictive woman, and there had been more than a few scenes between us over the years. We both liked to shoot guns and had gone to the shooting range together several times when Anne and I had first met, but soon even that stopped. One evening, after a particularly heated exchange, I was out in the backyard, sitting in a lawn chair and drinking another gin, while Anne was inside trying to patch things up yet again. I heard the door open and assumed it was Anne, so I said, “Is everything straight with the old bitch?” only it was Beverly. I hardly cared. I don’t think she did either. She sat down next to me and for awhile we didn’t even look at each other and we didn’t say a word. Finally, she said, “Thomas, you and I will never like each other so let’s just stop this charade.” I glanced over at her and then turned away again and returned to my gin. “There is only one reason that I haven’t disowned Anne for marrying you. Do you know what that reason is?”

I drained my glass and said, with full sarcasm, “You mean, because she loves me and you want her to be happy.”

“That would be two reasons,” she sneered. “Distinct reasons. And, yes, while she certainly does love you that is most definitely not it.” She seemed to be waiting but I didn’t say anything. Eventually, she continued: “I tolerate your presence only because I believe that you would give up your life for my daughter and that, to me, is all that matters.” I sat up in the chair. Now she had my attention. She went on: “Romantic love is a common, fickle thing and it comes and goes, but safety, real protection, that’s very rare. And the world is dangerous. I want you to know that however ugly things get between us, whatever is said or done, in the end, all of it is nothing to me as long as you take care of my little girl. Do you promise me that you always will?”

I told her that she was right, that I would lay down my life for Anne in an instant, and she had my word that I would protect her daughter. After that, Beverly and I still had some vicious, nasty rows, but after each—and especially after the worst—we would always manage to exchange a private glance, sometimes with a smile; all was forgiven, Anne would be safe.

I hadn’t spoken to Beverly since Anne and I had begun the divorce proceedings. Anne had once told me that when she’d told her mother that we were splitting up she’d been surprised at how upset her mother had been. “I thought she didn’t even like you--actively hated you, in fact--and she broke down crying. I’ve never even seen her cry before.” Now I’d finally let Beverly Michaels down and I wanted to tell her that Anne’s murderer was dead, that I had at least seen to that. It was not enough, but it was all there was, and I knew I would have to find some way to tell her very soon.