(CONTINUED) Twenty-One

I spent most of the next day in my room, looking out the window or lying on the bed, trying to guess how long I could live this way. One minute I would think I could keep it up indefinitely, as long as the police didn’t find me. The next minute I would be plunged into despair so profound I’d consider calling the cops myself. In the late afternoon I went for a walk through town. I almost stopped by the gallery, but Julie and I had made no plans and our parting the night before had been unsatisfying so I decided to leave her alone.

When I got back to the house Mary was already home. I heard quick footsteps upstairs as I came in the front door and then silence. I wondered if she’d been reading the Chekhov story. I sat down by the piano in the living room and leafed through a first edition of Lolita. I’d never even seen one before; it was probably worth $2,000.

In a few minutes Mary came downstairs and asked me to have dinner with her again. I had no reason to refuse, so I asked her if she needed any help. She told me to just sit tight and relax. Then she laughed: “But be careful with the first editions.”

Soon I could smell garlic and onions and chicken. Fajitas. I wondered if my face was being shown on television back in San Francisco: “Wanted in connection with a brutal double homocide.” And my unborn child could be counted as a third murder. Would the story go national? I made a note to pick up some out-of-town newspapers the next day. I considered whether I might have to start running again and I didn’t know if I had it in me. Finally, Mary called me out to the dining room.

I sat down in front of nearly a dozen small bowls and plates. Cheese, beans, peppers, carrots, sour cream, guacamole, pico de gallo, beans. I didn’t know whether Mary’s generosity was driven by kindness or loneliness. I told her that the food looked delicious and thanked her for the effort. She smiled slightly and nodded, then spooned some beans onto a tortilla and handed the plate to me. In contrast to the day before, she seemed quieter, more reflective. I imagined that she was watching me, looking for clues one way or the other, her strange new boarder making her more and more curious. We ate in silence until Mary said, “Julie told me I was right.”

I scooped a dollop of sour cream onto my food and said, “Excuse me?”

“I told her you were divorced. She said I was right.”

I took a bite and chewed slowly. Once again we were heading into dangerous territory.

“How’d you know?”

“Oh, a person can tell when a man has been close to a woman for a long time. There’s something about the way he carries himself, something in his face and in his eyes. It’s a kind of seriousness; an intensity, maybe. Anyway, I can tell. Maybe that’s because I was married to Dane for 42 years and I could see it in him.” We both grabbed for bowls and spoons, heaping lettuce and tomato onto our plates. “But it didn’t take 42 years to see how being with me changed him. I think I noticed it sometime in the fifth year we’d been living together.”

“Then, is this thing you see—is it a good thing?”

Mary frowned. “Well, yes and no. I think there’s good in it—tenderness and patience and a real appreciation of what it means to love another person. A knowing. But there’s also pain and self-doubt and the resentment that can come from dreams deferred.”

“But you and your husband never divorced,” I said.

“That’s true. But it doesn’t matter. Staying married is hard work. It can be more painful than separating, which is why people break-up.”

We both went back to our fajitas, eating in silence. When we were finished Mary asked me if I’d like some Mexican coffee. I said I would and she made us two cups and came back to the table. She blew across the top of her cup and a little swirl of steam rose up and died away. I sat back and waited for mine to cool a bit.

“Julie said she had a nice time last night. She’s been talking about you a lot around the gallery.”

I laughed and reached for my cup. “I’ve gathered that a few words have been exchanged between you two.”

Mary didn’t laugh or even smile. She looked at me over the top of her cup and said, “Did she tell you about her family?”

“Yeah,” I said. “She told me her mom still lives in town and that her father left when she was young. She also said she has a younger brother.”

Mary nodded. “Is that all she said?”

“Yeah, pretty much.”

She sipped at her coffee again and I watched her uneasily. “I know you two have secrets” she said. “We all do. It can’t be helped. I don’t know what yours are, but I do know some of hers. I’m going to tell you a few of them and the only reason is because I think you’re both in trouble. I’ve thought about this a lot over the last two days and neither of you is going to get very far the way you’re going. By that, I mean I think someone is going to get hurt. Romantically, I don’t know. That’s not my place. But I do believe you can help each other and if I have to put my nose where it doesn’t belong for it to happen, I’m willing to do it. But, before I go on, let me ask you, how do you feel about her? If I’ve read things wrong then I don’t want to tell you anything that might put her in a compromising position. So, please, just be straight.”

I ran my middle finger along the lip of my cup and watched the surface of the oily black coffee ripple. I didn’t really know what to tell her, so I said, “I think I see something—recognize something. But I’m not certain yet. I could be wrong.”

She nodded. “I don’t think you’re wrong. I think you just need more time and I’m not sure you have it.” I turned to Mary suddenly, wide-eyed. She was on to me, I was sure. She’d read something or seen something or done some investigating. I began to speak, but she stopped me. “Don’t worry. She’s not sick or anything. It’s just that certain things need to be dealt with.” I leaned back in my chair. I could feel my heart beating. I had no idea where this was going. “Let me go back a bit. Julie’s father did leave when she was very young. I remember it well. It made the papers here in Santa Fe. Her father—Edmund was his name—was a judge. He was a mean, unfair man with a wicked temper. He was often drunk on the bench and who knows how many innocent people went to prison because of him. Or how many guilty people went free. Julie has told me that he would beat her and her mother terribly. Just after her brother was born Edmund was arrested at a brothel up in the mountains, out near Socorro. Edmund was disgraced and left town one day without a word. It should’ve been the best thing that had ever happened to that family, except that Julie’s mother couldn’t handle keeping up the household anymore. She wouldn’t go outside either, because she thought people were staring at her.” Mary paused and drank from her cup. “And I suppose some people were staring at her. Anyway, she started to get a little funny and that meant that Julie had to raise her brother. She tried to do everything for him—cooking, helping him with his homework—but he started getting into trouble very early. There were fights and drugs and arrests by the time he was in junior high. At some point Jimmy—that’s his name—started living on the streets. Hustling, I guess you’d call it. Drug dealing. Petty theft. Soliciting. It broke Julie’s heart to see her brother destroying himself, but there was nothing she could do. He wouldn’t listen and he wouldn’t accept any help, not even from his own sister.”

Mary stopped for a moment. “You know,’ I said. “I’ve seen them together. They seemed to be getting along okay.”

Mary nodded. “Julie told me about that. You see, they do get along. Jimmy would do anything for Julie. The only thing he won’t do is let her help him.”

“Julie did call me several days ago, looking for him. That was a little odd.”

“Yes, this is where the real trouble starts. Julie thinks that Jimmy has really gotten himself into trouble. She doesn’t know whether it’s drugs or stealing or what, but she says that he’s scared, even though she tells him everything’s fine.”

“And you think she’s right.”

Mary took our empty cups and walked them to the sink. “I’m sure she’s right. I overheard him talking to a man in the plaza one day. I couldn’t make out everything, but I heard this man tell Jimmy there would be trouble for him and Julie if something wasn’t fixed. I don’t know what this ‘something’ is though.”

My desert oasis had vanished. I’d known that I hadn’t deserved what I’d found in Santa Fe. Now everything had changed in an instant. I let out a long breath as Mary returned to the table.

“I just wanted you to know this. Julie is very frightened for Jimmy. If anything happens to him her world will collapse.”

“I’m not sure what I can do,” I said.

She leaned forward, her elbows on the table. “I want you to think of something.” It sounded like a threat. I wondered again how much she might know about me. The she softened: “So now you know. Anyway, how’s the writing been going?”

That night, lying awake in bed, I thought about secrets and lies. The things we say and, more importantly, the things we don’t. Now I knew that I had recognized something in Julie. I also knew that I no longer had any power over it.

Twenty-Two

The next day was Thursday and after Mary had left I walked down to the international newsstand. I bought a day-old San Francisco Examiner and a USA Today. I got a cup of coffee and a croissant from a café and found a bench in the plaza. After I’d finished eating I sat there for a long time, drinking the coffee, the papers folded next to me. I looked at my phone messages, deleting two more voicemails from my agent and a few from old friends that I knew couldn’t help me. I saved three from Ruben but didn’t listen to them. The last call was from Anne’s mother—I didn’t even think she’d had my number—and I knew I’d have to listen to it. But first I picked up the SF Examiner and flipped through to the Metro section. It had been nearly a week since Anne’s murder and, unless there’d been some new development, I doubted that they’d still be following the story closely enough for a feature. I hoped there wouldn’t even be a mention, but there was, toward the back of the section:

“Bay Area law enforcement officials are continuing their requests for the public’s help in finding the chief suspect in last Saturday’s double homicide. Anne Gould and her boyfriend, Steven Foster, were found dead in Ms. Gould’s Walnut Creek home on Sunday morning, after Ms. Gould failed to attend a family function. Police officials have called the murders ‘brutal and cold-blooded’ and are looking for Ms. Gould’s ex-husband, Thomas Gould. Gould, author of the best-selling novel, “Cries from the River,” has not been seen since the day of the killings and police are asking anyone with information on Gould’s whereabouts to immediately contact the Walnut Creek Police Department. Mr. Gould should not be approached as he is considered armed and dangerous.”

There was a small picture of me accompanying the piece but it was grainy and several years old. The photos they’d used for the TV coverage had probably been better. I now knew that Ruben had told the police he’d seen me--he couldn’t have said much more--but I hadn’t learned anything else. There was no mention that Anne had been pregnant and no description of the murders themselves. I had some hope that Anne’s death would be linked to Steve Foster through his gun but there was no indication that it had been. I figured that more information would’ve been included in the stories earlier in the week. I picked up the USA Today and leafed through it, but found nothing. It was small comfort.

Waves of fear came over me and I sat on the bench waiting for them to subside but they didn’t. I was not famous, but I was known and someone, somewhere who’d heard about the killings would eventually recognize me. For awhile I once again considered turning myself in. More than anything I wanted to be cleared of Anne’s murder--I could confess to killing Steve Foster--but I had no confidence that the truth would be accepted. And even if it was, I didn’t want to go to jail for Foster’s murder. When I thought of his body lying on the carpet, nearly headless, I knew that I wouldn’t be contacting the police.

I picked up my phone and listened to the message from Anne’s mother: “Thomas, this is Beverly Michaels. I don’t know if you’re checking this phone but I want to say…” Her voice broke and there was a long pause. “…I want to say that I don’t think you killed Anne. The police say they aren’t sure, but I am.” There was another pause. She sounded sad and exhausted, utterly and finally defeated. “I want to ask you to contact me somehow and tell me what happened. I don’t care how you do it. Please do me that dignity. I need to know.” She sniffed. I wondered if she knew Anne had been carrying my child. “Tell me she didn’t suffer.” There was some rustling and then the line clicked off.

I had never gotten along with my former mother-in-law. She was a proud, vindictive woman, and there had been more than a few scenes between us over the years. We both liked to shoot guns and had gone to the shooting range together several times when Anne and I had first met, but soon even that stopped. One evening, after a particularly heated exchange, I was out in the backyard, sitting in a lawn chair and drinking another gin, while Anne was inside trying to patch things up yet again. I heard the door open and assumed it was Anne, so I said, “Is everything straight with the old bitch?” only it was Beverly. I hardly cared. I don’t think she did either. She sat down next to me and for awhile we didn’t even look at each other and we didn’t say a word. Finally, she said, “Thomas, you and I will never like each other so let’s just stop this charade.” I glanced over at her and then turned away again and returned to my gin. “There is only one reason that I haven’t disowned Anne for marrying you. Do you know what that reason is?”

I drained my glass and said, with full sarcasm, “You mean, because she loves me and you want her to be happy.”

“That would be two reasons,” she sneered. “Distinct reasons. And, yes, while she certainly does love you that is most definitely not it.” She seemed to be waiting but I didn’t say anything. Eventually, she continued: “I tolerate your presence only because I believe that you would give up your life for my daughter and that, to me, is all that matters.” I sat up in the chair. Now she had my attention. She went on: “Romantic love is a common, fickle thing and it comes and goes, but safety, real protection, that’s very rare. And the world is dangerous. I want you to know that however ugly things get between us, whatever is said or done, in the end, all of it is nothing to me as long as you take care of my little girl. Do you promise me that you always will?”

I told her that she was right, that I would lay down my life for Anne in an instant, and she had my word that I would protect her daughter. After that, Beverly and I still had some vicious, nasty rows, but after each—and especially after the worst—we would always manage to exchange a private glance, sometimes with a smile; all was forgiven, Anne would be safe.

I hadn’t spoken to Beverly since Anne and I had begun the divorce proceedings. Anne had once told me that when she’d told her mother that we were splitting up she’d been surprised at how upset her mother had been. “I thought she didn’t even like you--actively hated you, in fact--and she broke down crying. I’ve never even seen her cry before.” Now I’d finally let Beverly Michaels down and I wanted to tell her that Anne’s murderer was dead, that I had at least seen to that. It was not enough, but it was all there was, and I knew I would have to find some way to tell her very soon.

I got up off the bench and walked back to the house. I was a man on the margin of existence, without reason or purpose, set apart as a condition of my freedom, which was no freedom at all. I went up to my room and sat at the desk. I picked up a pen and held it over a clean notepad. Minutes passed. I wanted to write myself into another world, another life, and I gripped the pen and stared at the paper, almost as if I believed it could be possible. But when I tried to think of what other life there could be for me, how my circumstances might be different, I couldn’t see anything. It seemed like I hadn’t written my life, but that I had been born into it and simply followed the story, always getting closer to the conclusion. Only where before the end was a mystery, it now seemed to be getting clearer to me. I began to write it:

“The officer pulled him over just across the Oklahoma/New Mexico line. When he’d seen the squad car in his rear view mirror he’d pressed his foot firmly to the accelerator. A few moments later he’d heard the siren and saw the lights. He pulled over and leaned his head against the wheel, waiting for the officer to approach. He was tired and sick and out of places to go. The officer came to the door and he rolled down his window. He gave the cop his license and registration. The officer went back to his vehicle and he waited. When he glanced in the rear-view he saw the officer talking on the CB. A few seconds later another squad arrived and a second officer got out. Then the two officers began to approach his car, guns drawn. He smiled and grabbed a wrench out of the glove compartment; it didn’t much look like a gun, but it would work. Then, in one quick motion, he opened the door and stepped outside, pointing the wrench at the officers…”

I stopped and tore the sheet of paper off the notepad. Then I crumpled the sheet into a tight ball and threw it in the wastebasket. There wasn’t much I knew about the way things would go, but I had just ruled out one ending.

That night Mary made stuffed tamales for dinner. We sat and ate and she didn’t say much. I didn’t say much either. When we were finished I helped her clean up and then went to my room and lay down on the bed. Some time during the night I fell asleep. (CONTINUED)

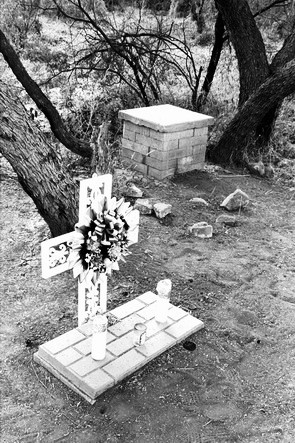

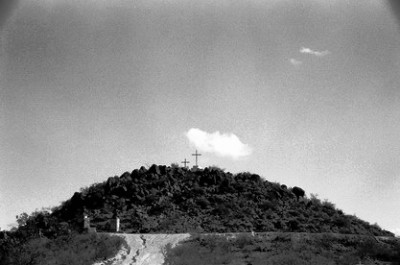

All photos taken at or near San Xavier del Bac Mission, Tucson, AZ, USA.

Love your story and wanted to point out some character insertion errors -

ReplyDelete"Mary has told me that he would beat her and her mother terribly."

"Petty theft. Soliciting. It broke Mary’s heart to see her brother destroying himself, but there was nothing she could do."

"Mary thinks that Jimmy has really gotten himself into trouble."

Mary? s/b Julie? There are too many Mary's in episode 21.

Thanks very much! You're absolutely right. I've actually written well ahead of what's posted, but my editing process is WAY behind. Still, I want to get the chapters up. So, again, THANKS! I REALLY appreciate the help and your kind words. (And folks should check out STORY BLOOK, a cool site featuring serialized fictional tales.)

ReplyDelete