(CONTINUED) Thirty-One

The restaurant was called Rosarita’s and it was very dark inside. There were strings of tiny bulbs—probably Christmas lights—around the windows and along the top of the ceiling. It was a big place, with dark red carpet and red tables. Deep booths lined the walls, but it was late and there weren’t many customers. The hostess got up slowly from the chair she’d been sitting in and showed us to a booth. Our waitress brought us two glasses of water and menus. It was hard to know what to order.

“Are you alright?” I asked Julie.

She leaned forward and rubbed her eyes; they were still red. “I don’t know. I feel weird. None of this seems real. Maybe I’m just tired.”

I nodded. I felt the same way. Only I was starting to get used to the feeling. It occurred to me that I might feel like this for the rest of my life. “But I do like the desert,” I said, “Even at the worst of times; maybe especially at the worst of times.” I asked Julie if she’d ever lived anywhere else.

“I’ve never even thought about it,” she replied. “Maybe because I couldn’t imagine leaving Jimmy. Or maybe I just never had a reason to go anywhere else.” She hesitated a moment, then went on: “All my friends are in Santa Fe. I like working at the gallery. Even after all this time I think it’s a beautiful city.”

“It is,” I agreed.

The waitress came back. I asked for huevos rancheros and hash browns. Julie ordered a plate of nachos, the “Grande Plato.”

I didn’t know whether I should say what I had to say right then, but I figured it might be the last bit of calm for awhile, so I told her, “We can’t go back there, you know. Even if it goes better than we have any right to expect.”

“I know,” she said. “I’ve been thinking about that. I left a lot behind.”

I tell her that maybe Mary can pack up her apartment, that there might be a chance we can retrieve some of her belongings. I don’t know if that is true, but I hope that it might be. Then I ask her if there’s anywhere she can think of that would be safe to go. Maybe some place where she knows someone that could help us, someone like Mary.

She thought for awhile and then shook her head. “I can’t ask anyone to get involved. Mary can take care of herself. But what would I say to somebody else? How could I tell them?”

She was right and I was happy and I didn’t want to think about why.

“Do you know anyone?” she asked.

I thought of Ruben and shook my head. “I’m afraid I’ve burned a few bridges lately.”

Julie ran her finger down the condensation on her glass of water and said, “I haven’t even told my mother.”

The waitress brought our food and I started to feel better after the first bite. The portion was huge, but I quickly made my way through it. Then I started to help Julie work on the nachos; it really was a grande plato.

“I think we should go to Mexico,” I finally said.

Julie stopped eating. “Mexico? How will we get across the border? I don’t have a birth certificate or passport and neither will Jimmy.”

“If we go across at Sonora and act as if we’re going to stay within the border zone we might be able to get through with just our driver’s licenses. Or maybe we could leave the Jag on the U.S. side and walk across. I don’t know. We’ll have to see when we get there, but I think we should try.”

Julie ate another nacho and then said, “Okay.” Just “okay,” resigned, like there was no other option.

But for the first time in a long time I began to feel a spark of optimism. I thought that if we could make it through the next day then there might be a way out—completely out—for all of us. Yet I knew that the “if” was very big. And then, after that, we’d still need some luck at the border.

We finished our meal and I paid the bill with the last few dollars I had. I felt a little anxious to be out of money but then remembered that there were thousands and thousands of dollars back at the motel; it hadn’t occurred to me until then that petty cash was the one thing I didn’t have to worry about. When we returned to our room it was after midnight and as I closed the door Julie took my hand in hers. It was dark and I pulled her toward me and we kissed and then we kissed again and I ran my fingers through her hair and down her back. I took off the suit coat that had belonged to Mary’s dead husband, unbuckled the shoulder holster, and put the gun on the dresser. Julie unbuttoned my shirt and pulled it off me. After awhile we laid down on the bed and I took off her jeans and blouse and we kissed some more and then we stopped. I looked at her and she traced her fingers along my lips and I touched her cheek. “It’s too much,” she said. “I don’t want to feel this. Not until I know I’ll be able to feel it again.” I nodded and reached one hand down to pull the covers over us. She kissed me one more time and turned away, keeping my other hand tightly in hers and held to her chest. I pulled her close to me and, though I could not be sure, I thought that before long she was asleep.

Thirty-Two

I laid in bed for awhile listening to the cars and trucks on the interstate, trying hard not to think of what the next day held in store. I could faintly smell Julie’s shampoo and I remember that it reminded me of coconut and strawberries. It struck me that the combination seemed unusual and that’s the last thing I recall before thankfully--mercifully--falling asleep. When I woke I couldn’t tell what time it was. I could see light around the window, but the thick curtains made it impossible to tell if it was 6 AM or noon. We’d left the air conditioner on and the room seemed cold. Julie was still in my arms but I knew she was awake because she was squeezing my hand harder than she would have if she’d been asleep. I looked at the clock: 8:54 AM. I was glad for the decent night’s rest.

“How are you?” I asked.

“Scared,” she said, turning over to face me.

“Yeah, me too.”

We kissed and held each other.

“I want to thank you,” she said, her hand against my cheek. “You didn’t have to do this.” She looked sad and frightened and beautiful.

“You don’t have to thank me. Not now or ever. I should thank you.” She looked at me and I knew she didn’t understand. I wondered if I should tell her about what had happened back in San Francisco, but I immediately thought better of it. We already had enough to deal with on this morning. “When this is over you’ll know all about me,” I said, then pulled her to me again.

We kissed for awhile longer, running our hands over each other’s shoulders and stomachs and arms. In her touch I could tell that she was determined to do whatever had to be done that day. She’d found that reserve of strength that each of us must locate if we’re to get through the most dangerous times in life, those times that will destroy us if we aren’t strong enough for them. She would do whatever was necessary to save her brother or die trying.

Finally, I got out of bed and got some clean clothes and went to take a shower. When I came out of the bathroom Julie was standing in the middle of the room. She had taken the .38 out of its holster and was holding it in her hand, the barrel pointed to the floor. “I don’t know if I can use this,” she said. “I’ve never shot a gun in my life.” I went around behind her and raised her arms. I told her to grip the gun with both hands and hold it steady in front of her. Then I stepped away. “There won’t be much kickback with that gun, but there’ll be some. It’ll be loud, so don’t let that scare you. Just hold it as straight and level as you can.”

“Do you think I’ll have to use it?” she asked.

“I hope not,” I said. “We’ll have all kinds of trouble if it comes to shooting. Hopefully you won’t even have to take it out of the holster.”

“Then what are we going to do?”

I started putting my shoulder holster back on. “I’m not really sure. Maybe we can just give them what we’ve got and that’ll be the end of it. After all, this is all the money we could get.”

“What about the things at the gallery?”

I took the 9 mm out of the holster and checked the action. “I don’t believe they gave us time to sell many paintings. Besides, they’re not yours.”

Julie went to the bathroom and I sat back down on the bed and waited. I felt like I had a clear purpose and, at that moment in my life, it counted for something. But I worried that I wouldn’t be able to protect Julie. Her safety was my main concern and I was going to make sure that as long as I was up and breathing nothing would happen to her during whatever was to come.

It was 10 o’clock when Julie and I walked back over to Rosarita’s. I doubted she had an appetite and I didn’t either, but I wanted us to have something to eat. I asked her to put the .38 Special on before leaving the motel, but she insisted we wait until we got back. We had eggs and pancakes and coffee and Julie told me a story about how her brother had gotten himself stuck in a concrete drainage pipe when he was six. The fire department was called out to free him but after an hour of trying Jimmy was still in the pipe. It was determined that they’d have to crack the pipe but they didn’t want the ground to collapse and crush him. So, they’d brought in a backhoe and very carefully dug the soil off the top off the pipe. They’d had to work slowly and as the hours passed the whole neighborhood came out to watch. Some people brought food and water which they pushed in to Jimmy by using metal extension poles of the kind used to clean leaves out of gutters. When it got dark the firemen set up giant arc lights to work by. Finally, the pipe was exposed and a jackhammer was used to crack the concrete. Afterward, pale and cold, Jimmy had said that the jackhammer had made the pipe vibrate so much that his bones ached and he felt like his skin was humming. It had taken thirteen hours to free Jimmy and that night Julie had cried herself to sleep with relief, vowing never to let anything bad happen to her brother again. At the time she couldn’t have known how difficult a promise that would be to keep.

We paid our bill with some cash I’d taken out of the bag and went back to the motel. It was 11 o’clock and we decided to go over to the payphone. I helped Julie put the holster on and she trembled a little as I pulled the buckle snug. Then she put a windbreaker on over the gun and we put the money and our bags in the car. I went to return the key and then we drove over to 9th Street and parked across from the Empire Laundry. The payphone we’d been told to go to was at the corner and we’d be able to hear it ring from the car. We sat and watched the traffic on the street, not saying much to each other. I kept my eyes open for the Land Rover or anybody else that might look suspicious, but didn’t see anybody. At 11:58 the phone rang and, although we’d never discussed it, I got out of the car and ran across the street. I got to the phone on the third ring.

“Hello,” I said.

“Who is this?” asked the voice on the other end flatly.

“Tom Gould. I’ve come from Santa Fe to pick someone up.”

There was a moment of silence. “Yes, I was told that Jimmy’s sister hadn’t come alone. Why did you work so hard to lose my man?”

“I have some problems of my own,” I said. “Being followed makes me nervous.”

“I see,” replied the man. “What kind of problems do you have?”

“I’d rather not say. It doesn’t concern Jimmy or his sister. It’s my own problem.”

Another moment of silence and then the man raised his voice: “I don’t have time to fuck around here. If you want that kid back you better let me speak to his sister.”

I leaned into the phone and lowered my voice. “Listen, I don’t give a damn about the kid. Whether he lives or dies doesn’t mean a fucking thing to me. He’s going to wind up dead someday soon anyway. I only care about making sure nothing happens to his sister. That’s why I’m here. So, you deal with me. I read the note you sent and it said nothing about her coming alone.”

I held my breath for a few seconds and then the man laughed. “Fine, have it your way. I’ll tell you where to drop off the money and at that time you’ll be told where to find Jimmy.”

“No,” I said. “We’ll meet you in a public place, somewhere downtown.”

“I’m afraid I can’t do that,” the man replied. “Maybe you should speak to Jimmy.”

I heard some rustling on the other end and then Jimmy came on, his voice high and ragged. “Julie!” he yelled. “Don’t…” There was a loud thump and then I heard garbled shouting and more thumps. The man came back on the line: “I guess he doesn’t want to talk to you. It sounds like he’d like to speak with his sister.”

“I told you I don’t care if you kill him,” I said. “It’s only because his sister does that I’m trying to keep him alive. But you have to give us something I can work with.”

A few more moments of silence passed. “Okay, there’s an abandoned house at the end of Vallejo Drive, out beyond the Yaqui Indian Reservation. It’s south of town, off I-19. We’ll be inside with Jimmy and we can do the exchange there.”

“Fine. What time?”

“3 o’clock. And if you bring guns we’ll kill Jimmy, his sister, and you.”

Then the phone went dead.

Julie watched me walk across the street. “Is Jimmy okay?” she asked, as I got in the car.

“Yeah, I talked to him,” I said.

She was visibly relieved. “What do we have to do?”

“We’re going to meet them at an old house south of town, near the Indian reservation. He said to be there at 3 o’clock.”

She bit her lip. “I don’t like it.”

I started the car. “No, me either.” (CONTINUED)

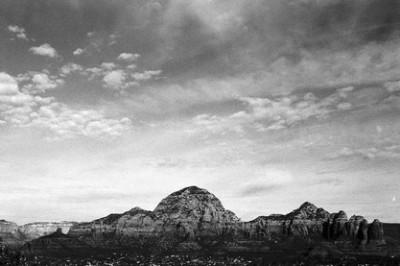

The top shot was taken on Route 66, Gallup, NM. The middle photo is the view across Sedona, AZ. The last photograph is 9th St., Tucson, AZ. We'll wrap this up next time.

Love the photos. The Golden Desert Motel is, indeed, on Route 66 but is actually in Gallup, NM - not Flagstaff, AZ.

ReplyDeleteDoug, you're absolutely right! That's been up for many years and no one has caught it. You win a prize! (The prize being my undying respect for your knowledge of Route 66!)

ReplyDeleteThanks!

JM