Like Hillsboro, Kingston, New Mexico isn’t a ghost town. But it’s also not the place of which it was said that on nights when the miners had been paid you couldn’t walk ninety feet in 30 minutes for the crowd, a place with 22 saloons, 14 grocery stores, three hotels, three concurrently-operating newspapers, an opera house, and a school, a place where the bank once held $7,000,000 in silver and the population topped 7,000. Nope, it’s not that place now. And it never was. There may be few Old West mining boom towns that have had their history so exagerrated. Kingston has even been considered to have once been the biggest town in territorial New Mexico.

Now, everyone agrees that in the early 1880’s precious metal, particularly silver, was found in the area. Ralph Looney’s Haunted Highways recounts the story that Kingston’s establishment can be traced to a drunkard, Jack Sheddon, who became such a nuisance in Lake Valley that the sheriff put him on a burro with food and whiskey and sent him north. En route to Chloride, he made a stop near what would become Kingston, had a good long drink, and passed out on a rock. When he came to, he noticed that his stony pillow had flecks of metal in it. This was bornite, a silver ore, and he quickly established the Solitaire Mine. Soon prospectors were descending from every direction. It’s a great tale, but not really true. Prospecting was underway before Sheddon even arrived (he at least did exist) as a few miners had already moved the 10 or so miles west from Hillsboro, which had been established in 1877.

(The above photo shows a house that was also once a store on Kingston's eastern edge. The sign in the window says, "Dr Dans Medicine Show 1/22/11". Near the bottom of this post is a shot of the microwave tree around the side. Interesting, eh?)

In the fall of 1882, James Porter Parker, General G.A. Custer’s former roommate at West Point, platted Kingston, which took its name from a local mine, the Iron King. Soon it was reported by the Tombstone Epitaph in Arizona that there were 45 men working area mines. By 1885, a year after Kingston’s oft-reported peak population of 7,000, Territorial Census figures show 329 residents in Kingston and the adjacent Danville Camp combined, even with Spanish and Chinese included in the tally.

It may well have been a rowdy place though. In an 1886 edition of the St. John’s Herald out of east-central Arizona (at the time Kingston didn’t have one newspaper) a citizen expressed upset at their town’s lack of a school, church, or, indeed, any public institution. Reverend S.W. Thornton even referred to Kingston as “the typical mining town in all its wickedness.” In 1888, construction of a stone church began which would serve Kingston’s now-1,000 residents. Sometimes claimed to have been spontaneously financed by prostitutes, gamblers, and dancehall girls, it’s more likely that Rev. N.W. Chase solicited the funds.

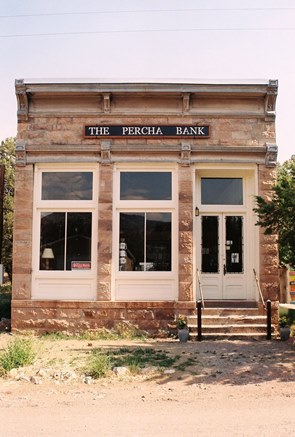

In 1890, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, Kingston’s population reached 1,449, a count it probably never surpassed by much. The 1893 economic panic sent silver prices crashing and the number of Kingston’s occupants plummeting quickly back into the low hundreds at best. By the time it was really all over in the early 1900’s almost $7,000,000 in precious metal had been mined in the vicinity, not an inconsiderable sum. But it took over 20 years; that amount was never in the Percha Bank at one time.

Even the usually no-nonsense Philip Varney slips up when it comes to Kingston, mentioning in New Mexico’s Best Ghost Towns that Chief Victorio’s band of Apaches once descended on the town,

but because the miners were assembling a hunting party and thus had their firearms at hand they were able to quickly drive the attackers out. It’s said Victorio decided to leave Kingston alone after that and the happy populace named their new three-story hotel The Victorio in his honor. The problem is that Victorio died in 1880, two years before Kingston was established. It’s not entirely Varney’s fault; there are many stories about Victorio and his band’s depredations in and around Kingston. And Varney didn’t have Wikipedia in the 1970’s.

but because the miners were assembling a hunting party and thus had their firearms at hand they were able to quickly drive the attackers out. It’s said Victorio decided to leave Kingston alone after that and the happy populace named their new three-story hotel The Victorio in his honor. The problem is that Victorio died in 1880, two years before Kingston was established. It’s not entirely Varney’s fault; there are many stories about Victorio and his band’s depredations in and around Kingston. And Varney didn’t have Wikipedia in the 1970’s.You may also hear of the ironically-named Virtue St., on which was an infamous Kingston brothel. While you will find a very short side street named Virtue today, it was created after Kingston's initial abandonment. But don't fret! The world has not gone entirely topsy-turvy; there certainly was a brothel in early Kingston.

Walking the two short thoroughfares, many have wondered how a town could’ve risen and fallen so precipitously. Since it didn’t, it’s not as surprising that only one historic building exists wholly intact: the Percha Bank. The old Assay Office, remodeled as a private home, and a vastly reconfigured hotel—The Victorio—also persist. Floods and fires have certainly done their damage, but there was never as much to disappear as is usually imagined.

Much of the confusion over Kingston is attributable to James A. McKenna’s classic Black Range Tales, which, it should be noted, contains the word tales in the title and not facts. Some of McKenna’s yarns, which most ghost town sources at least reference, take place in a Kingston of 7,000 rabble rousers,

"the metropolis of the Southwest" which, while possibly true to the spirit of the day, never quite existed. The same year that Black Range Tales was published, 1936, Madame Sadie Orchard told an interviewer of a peak population of 5,000. Few having actually been there, such wild overestimates made their way into subsequent Kingston literature. In the end, maybe the Kingston of myth is just one of those places in the Wild West of our collective imagination that people wanted to exist so badly that it was finally wished into being. It’s not the worst thing to have happened to history, I suppose.

"the metropolis of the Southwest" which, while possibly true to the spirit of the day, never quite existed. The same year that Black Range Tales was published, 1936, Madame Sadie Orchard told an interviewer of a peak population of 5,000. Few having actually been there, such wild overestimates made their way into subsequent Kingston literature. In the end, maybe the Kingston of myth is just one of those places in the Wild West of our collective imagination that people wanted to exist so badly that it was finally wished into being. It’s not the worst thing to have happened to history, I suppose.

Craig Springer, Black Range historian, founding member of the Hillboro Historical Society, and co-author of Around Hillsboro, does the best (and, to date, just about only) full-blown analysis of Kingston’s popular history, "Kingston Myth," in the June 2012 issue of Desert Exposure, turning up many inaccuracies and doing an excellent job of tracking down primary sources of more reliability. I reference his work throughout this post and thank him for his input.

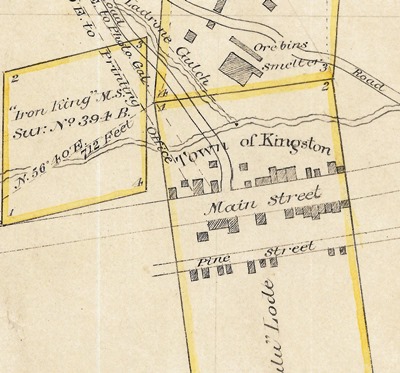

Below is the layout of Kingston circa 1887, which shows that three years after the town's supposed peak the place was still not real big. The plat is from the General Land Office of the BLM, which has all kinds of good stuff.

Most accounts of Kingston mention Victorio’s harassment, but a quick check of Wikipedia will confirm that he died on October 14, 1880. You might also have heard that Billy the Kid visited Kingston, but as he was shot by Sheriff Pat Garrett on July 14, 1881 in Fort Sumner it would’ve had to have been a very different sort of ghost town then indeed. Finally, if you’re in Kingston don’t forget to check out the real and factual Percha Bank, now a museum! Call before you visit as hours are limited.

Next post, I believe we’ll have a look at the newly remodeled Murray Hotel in Silver City. Then there will be a flurry of posts about towns on the eastern plains of New Mexico that not much has been written about. With such enforced brevity I might even be able to post more often!

If I may quote from the film, Raiders of the Lost Ark and Prof Jones who says to his college class: “This site also demonstrates one of the great dangers of archeology, not to life and limb, although that does sometimes take place, I'm talking about folklore.” You know the scene. Then again in the same movie, they claimed that Tanis was destroyed in a sand storm circa 950 BCE, (actually it survived another 1,500 years when the canal and lake silted up) but that is another ghost town and another story.

ReplyDeleteYep, local tall tales, small town boosterism, and looney old coots at the general store all tend to pass out interesting but erroneous information. Then again we have Hollywood and the History Channel.

As you well know, CoastConFan, a person must spend considerable time trying to sift through the half-truths, rumors, and exaggerations that accumulate over dozens and dozens of years. Then I might still get it wrong. Some things you figure you'll just never be able to verify.

ReplyDeleteThe Black Range of New Mexico presents special problems because the main "historical" text has become McKenna's wonderful but not-exactly-true Black Range Tales. I sympathize with Prof. Jones. JM

Regardless, the ability to go out there find the clues, i.e. rusty 1920s Ford pick ups with scraps of wood in the flatbed, is what makes traveling down two-lane highways exciting.

ReplyDeleteAs for trying to decipher truths from tales, it takes a plethora of research from as many accounts as possible. Remember, history is written by human beings, so the total truth never reveals itself in its entirety. However, if we can look for more sources and try to come up with clues, we can at least come up with reasonable hypothesis and then let readers and other people add their two sense.

You're absolutely right, Gregory. In the name of a plethora of research, I'd love to find a copy of a Forbes Magazine from 1921 that contains a feature on former Kingston resident (and defendant in the Teapot Dome Scandal, later acquitted) Edward L. Doheny. He might've been one of the first to exaggerate Kingston to a wide audience via that piece.

ReplyDeleteAnyway, I digress! Thanks for your thoughtful comment! JM

Speaking of Teapot Dome (and digression) and the NM connection, a friend of mine had a lease on a site in Oro Grande (Jarilla Junction was the stop on the El Paso and Northeastern RR), in the 1990s which was supposed to have been owned by one of the defendants of the Teapot Dome scandal. The mine closed when gold plummeted in the Depression.

ReplyDeleteWe went down to Oro Grande a few times to his lease site and played around by bringing up some buckets of dirt and then panning them. There was a bit of wire and a flake or two, but hardly worth the effort and it certainly didn’t even pay for gas. Then again gas was about a dollar a gallon and gold was about $350 a pure ounce. The big problem was that with no water available it was a big pain to bring it so you can pan a little bit. I wonder of Bill Ward, who had a rock shop and sometimes café in Oro Grande is still alive, it’s been years. Darn, see how fast I can drift off topic.

@ JM, a 1977 El Paso Times article that would be helpful in doing an Oro Grande blog entry. http://elpasotimes.typepad.com/morgue/2012/06/1977-orograndeit-can-be-drygulch-or-bonanza.html

I think water must've been a big problem! In that piece in the El Paso Times, Mike Musgrove says, "...where in the hell did they (3,000 residents) get their water? I've always wanted to know." I wonder if maybe a little population inflation ala Kingston went on.

ReplyDeleteI should definitely get down to Orogrande. I've heard it's also possible to see the small cement monument which marks where Pat Garrett was shot near Organ, NM. For a long time that was a secret, but I think the land was purchased for development and people want to make sure the monument is not destroyed. That would be a good day's trip.

http://friendsofpatgarrett.com

Thanks for the article! JM

Jarilla Junction is the train station and stop that serviced Oro Grande and Brice, both of which are down the road a piece, but I think the water tank and RR stop was there before the strike in 1905. Consider that steam locomotives generally had to fill up with water about every 30 miles to 50 miles or so if the didn’t have an attached tank car. That meant you had to have a watering station or tank (and generally a potential stop) at certain intervals for the thirsty engines. I think there was a pipe laid to bring water closer to Jarilla Junction from the Sacramento Mountains (if I recall correctly). Clearly water had to be supplied to boomtown Oro Grande and the much longer lived Brice, so running horse drawn water tanks back and forth to the mountains would have not been enough. Doing some research into railroad history would probably uncover where Jarilla Junction got their water.

ReplyDeleteBTW that is the source of the degrading term, “jerkwater town”. You see, you had to pull down the galvanized iron water tank spout to let water into the locomotive boiler and you had to pull hard (jerk) on the provided cord to swing and drop the spout into place. The derisive term indicated the only reason the train even stopped at a small place was to get water. Mail was not a reason stop at a town because the railroads worked out a system of dropping off and picking up mailbags on the fly.

Slightly more off track: another variation on “jerk” was the drugstore soda jerk (circa 1900), finally shortened to just “jerk” after the 1920s after it was disassociated with the soda later on. But of course, that is another story and has nothing to do with railroading other than jerk being a derisive term for people and towns. Ain’t etymology great? Hey, don’t be a jerk!

And, of course, when the big switch was made from steam to diesel locomotives, many of those little "jerkwater" towns went under very quickly indeed, including some of my favorites. Like, Yeso, NM for example:

ReplyDeletehttp://cityofdust.blogspot.com/2011/12/life-and-death-by-railroad-yeso-new.html

As for soda jerks, well, unless the drug store is abandoned such things typically fall outside my purview! JM

Very interesting. I've been trying to find information on Kingston in the 1880s since according to a later article:

ReplyDeletehttps://www.newspapers.com/article/evening-eagle-article-on-b-r-baker/154944737/

My 2nd great grandfather Byron Ray Baker allegedly ran a boarding house and eating house there for a bit. He was was from the Atchison area of Kansas where he was involved in shipping and freight so it certainly could fit he took the railway down that area. Later he would show up on the first day of the Guthrie Oklahoma land rush and live there with his family for about 10 years where he first ran an eating house, then a second hand store, was elected to his ward's council and eventually elected as City Marshal and Chief of Police... though within a year or so he left suddenly and went to Wichita Kansas where he stayed. An article suggests he was run out of Guthrie for taking bribes from grafters at a carnival while City Marshal lol. So it certainly could fit him being in a "wicked" mining town of Kingston at this time, but I've been trying to verify it.

In the same article it says he met his wife who was a waitress at a Harvey House in Rincon (my 2nd great grandmother). I can see there was a Harvey House Hotel in Rincon at this time but also have a challenging time finding records of her or them.