skip to main |

skip to sidebar

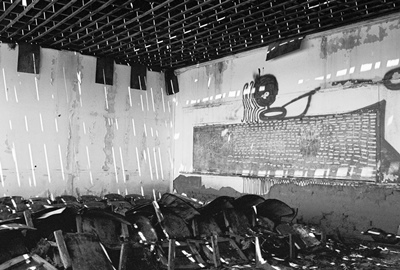

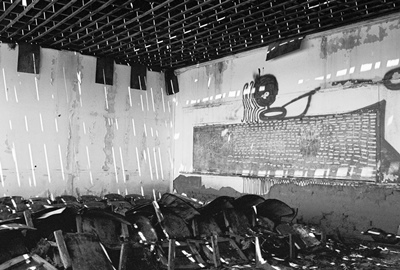

Despite the photo from Cedarvale, New Mexico above, this isn't a ghost town piece. Instead it's yet another story to fill in the time between my all-too-infrequent posts. This one is called...

THE WAR CORRESPONDENT

“You’re married? You’re fucking married?!”

I’m nearly—finally—asleep when suddenly a girl yelling in the room above mine jolts me back awake. My first reaction is one of pure anger. I haven’t slept in a very long time, and for the last 12 hours I’ve been nearly frantic to close my eyes. I’d driven over 36 hours straight with only a couple of quick naps at rest stops along the way. Out of nowhere Monday morning we needed to get a load immediately from our warehouse in Provo, Utah down to near Miami and my regular rig, which I could at least sleep in comfortably, was getting transmission work. All that was left to drive was a beat-up box truck, and between that and the tight deadline, decent sleep had not been in the cards. But I’d dropped off the load, gotten a quick bite, and checked into some place called the American Economy Inn not far from the beach to get my head down before starting the long haul back in the morning. So, I’m pissed to be awake. However, in another instant, curiosity takes hold.

“Oh my God!” yells the girl. Then an octave higher: “Oh! My! God!”

The man’s voice is deep and hard to understand through the floor. It sounds even and steady though. He’s trying to calm her down. There’s some stomping and another “Oh my God!” My stomach tightens and I’m ashamed of myself. Why should I feel anything for these people? I just want to be asleep. I hear the man again and make out a few words. “Baby.” “Her.” “You.” “Sorry.” I could fill in the rest myself if I wanted to.

Then there’s a crash and I wait for the inevitable. Real screaming. Harder stomping. All followed by a door slamming and then, maybe, a chance to get some shut-eye. I hope it won’t drag on too long, but then minutes pass with no sound at all. I listen harder, which only increases my wakefulness. Still nothing. Then there’s the unmistakable slow, rhythmic squeak of the bedsprings of a cheap motel mattress. Listening to other people have sex can be infuriating or depressing and in this case it’s both. So I turn on the light and put on my jeans and boots. The clock says 1:43AM. “Unbelievable,” I mutter, though there’s nothing remotely unbelievable about it. I wish I could call the guy’s wife. Not that I’m overly concerned about morality here, mind you, I just want some sleep.

There’s nowhere else to go so I get in the truck and turn on the radio. Two men are discussing ISIS in serious, somber tones. Where they come from, what they believe, how much money they have. In my exhaustion I’m struck by the thought that the modern world of dingy motels and run-of-the-mill adultery is going to have its hands full for quite some time battling the ancient world of religious martyrdom and apocalypse.

I listen to the radio for a while and must somehow eventually fall asleep because when I open my eyes I can see a thin paling of the darkness along the horizon just above the ocean. The clock on the radio says 4:52AM and a different man is talking about the weekend’s upcoming football games. My back and neck are stiff and I struggle to move as the blood painfully returns to my numb left arm, which has been pressed against the door. I turn the key, worried that the radio will have killed the battery, but the truck fires right up. So I cut the ignition, switch off the radio, and haul myself out of the cab. I’m too disoriented now to properly focus my anger on the couple upstairs as I stumble through the pre-dawn humidity back to my room where I sit on the bed, pull off my boots and jeans, and at last tumble into sweet oblivion.

Only the oblivion doesn’t stay sweet for long. Soon I’m dreaming that I’m wandering on a darkened battlefield amongst smoldering craters and mangled military equipment. Yet I can see no one either alive or dead. In my left hand is a camera and in my right a microphone but there’s nobody to speak to or document. I am too late for the war. The sense of failure is shattering, like I’ve let the entire world down. All those who might’ve fought here will go unnoticed and unremembered. As I walk slowly through the wreckage a hard, cold rain starts to fall, and the muddy ground begins to run with what looks like blood. But just as I’m about to scream I’m awoken yet again, this time by a knock on the door.

“Housekeeping!” I raise myself off the pillow and for a moment can’t recall where I am. Another knock: “Housekeeping!” The clock on the stand says 9:41AM.

“Not yet,” I answer, hardly recognizing my own wracked voice. “Half an hour, please.”

“Okay, sir,” is the reply through the door. “Sorry to disturb you, sir.”

I listen to the cart move further down the hall and then get out of bed and into the shower. In less than 30 minutes I’m walking across a sand-strewn parking lot toward the Flamingo Restaurant, a run-down 60’s-era joint next to the motel, with a voucher for a $5 breakfast. I sit on a faded pink stool at the blue and gold spangled counter, drink some coffee, and eat two runny eggs while I try to pull myself together. I think about how I didn’t plan on being a truck driver. I know plans don’t really mean much in life, but I never even made it to college. Then Cody came along before I’d turned 23 and that was that. I don’t mean to make it sound like Cody was the end of anything though. Really, he was the beginning. At 17, a junior in high school, he’s already a better man that I’ll ever be and I can’t claim any credit for that. He’s his own person, thankfully. For the last 10 years he’s lived with his mother and I’ve helped out as best I could. At first I’d visit only when I felt able to face him and his mom. It was harder when he was small, but it feels like it’s getting easier now. I’m grateful for that.

After breakfast I get in the truck and am about to hit the road when my phone rings. It’s my boss, Lindy.

“Dan, that was nice driving the last couple days. Damn heroic.”

“Thanks,” I reply. “I guess it was one for the books.”

“Sure enough. You made everyone happy.”

I almost laugh at that, but don’t.

“Listen,” continues Lindy, “take your time getting back. Find a couple places to stay. Some nice places. But, you know, maybe not too nice.” I do laugh at that. It doesn’t seem like there could possibly be a nice place between where I’m sitting and home. “And take the weekend off. In fact, I don’t want to see you ‘til Tuesday.”

I’ve worked for Lindy for eight years, often putting in six day weeks—sometimes even seven—and he’s always been good to me in return. It means something these days. It’s why I’ve stuck around.

“Thanks,” I tell him. “I appreciate that.” And I do.

“I know,” he says. “And I appreciate you handling this run. Now get back here safe.”

I tell Lindy I will and hang up. With the weekend free I figure I should give Cody a call and see what he’s up to. I make a mental note to do that later, telling myself not to let it slip like I have so many times before.

There’s a lot of road ahead of me. I’m still tired and I’d like to put in at least 10 hours before taking Lindy up on his offer. The sun sits low out over the water, gathering power. Happily, traffic is very light and moving fast. I get up to 80, about as fast as the old box truck will go, and start making good time. I’m fiddling with the radio, trying to avoid the news, when a car up ahead changes to the right lane without looking, pushing the car next to it off the highway. Then the first driver overcorrects in an attempt to get back into the left lane, slides sideways, and flips completely over, landing upside down at the bottom of an overgrown embankment. The other car has also flipped, but landed right side up on a flat spot near a swampy depression off the road farther back, its roof crushed.

I pull onto the shoulder and jump out of the cab. I smell the acrid tang of burned rubber. A puff of black smoke hangs in the air. A woman is screaming from the car that’s upright, but everything seems strangely quiet and still. I call 911 and tell them there’s been a serious accident. I give my best guess at the mile marker number and even though the operator tells me to stay on the line I hang up. The woman continues screaming, but I’m closer to the other car, so I run to that one, already breaking a sweat. At first I can see no movement inside. In the driver’s seat a man is strapped into his safety belt, hanging upside down against the roof. I kneel in the tall grass and yank on the door. It opens and I reach for him. He’s dazed and bleeding badly but alive. Then he opens his eyes wide and yells, “My son! My son!” He waves his hand toward the passenger seat but the child is actually lying on the roof, near the rear window, completely still. So much blood covers the man’s face that he can’t see his boy.

“He’s here, sir,” I say, surprised at how calm I sound. “I’m going to help him first.”

I run around the back of the car and smell gas. I know cars don’t usually blow up like you see on TV, but if there are fumes then the fuel system might no longer be sealed, and it occurs to me that maybe the vehicle is combustible. I kneel to get at the rear door handle and pull. The door is jammed, but I feel it give slightly so I try harder. It finally opens and I gently pick up the boy. He is perhaps six or seven and there is no blood on him at all. I think he must be dead but then his chest rises weakly. With the man’s son in my arms I run from the car to the grassy slope of the embankment by the highway and gently set him down in a patch of sparse vegetation. Some people have gathered and a middle-aged woman crouches beside me. She says she’s a nurse and begins to look at the boy. Without saying a word I get up to return to the man and it’s only then that I realize the woman in the other car is still screaming. Another man is trying to get her out of her vehicle, but I run back to the upside-down car and a third man follows me. This man and I work together to extricate the driver, whose scalp I now see has been partly torn from his skull, likely after hitting the spider-webbed windshield. He lapses in and out of consciousness as we undo the seatbelt carefully so he does not tumble onto the roof. The smell of gas is much stronger.

Quickly covered in the driver’s blood we slide him from the car. His left arm hangs limply from his side and it looks like his collarbone has been broken. We slowly carry him to the grassy slope and, as we do, I see the other man carrying the woman in his arms. She has not stopped screaming, but somehow it has become mechanical, the sound almost disembodied. The ground is wet in that direction and the man lifts his legs high to free them from the mud with each step as he moves towards us. We all converge on the slope and the woman is also covered in blood, a white stump of bone sticking through her thigh below her torn dress.

Finally I hear sirens growing closer and the state patrol arrives. Next come ambulances and a firetruck. We all step aside and let the paramedics get to work. Some firemen inspect the vehicles and then the firetruck begins to douse the car that’s upside-down. The injured woman suddenly goes quiet and is loaded into an ambulance. The man and his son are put in other ambulances. Bystanders begin to wander back to their cars. With traffic reduced to one lane, a line of vehicles snakes into the distance. Having seen the entire accident, I’m asked by the state patrol to provide a report. The officer goes through some questions and since there isn’t all that much to tell it’s over quickly. I’m given some forms to fill out with my contact information and it’s hard to keep the pen steady. Investigators arrive with measuring tools and tow trucks ease their way off the highway toward the crumpled vehicles. No one says, “Good work,” or “Nice job.” I’m not certain that I’ve done the right thing. Should I have done more? Should I have done less? I simply don’t know.

Then I walk to my truck and find the man who helped the woman doubled over behind it, vomiting. I try to light a cigarette but begin shaking and have difficulty getting the lighter to flame. The man straightens, wiping his chin with a sleeve, and I ask him if he wants a smoke. “I quit years ago,” he says, but an instant later reaches for the outstretched pack. Somehow I manage to light us both up and we stand there silently watching the wreckers and policemen. I’m quickly down to the filter and then all I can think to say is, “Be safe.” The man nods and replies, “You, too.” I climb into the truck and ease slowly into traffic that stretches far back along the highway, where tragedy comes fast and often.

It doesn’t take too many miles before I know that I need to get off the road. I’m halfway across the parking lot of a Super 8 when I remember there’s a lot of blood on my clothes. The woman at the front desk eyes me warily until I explain that I was just at the scene of an accident.

“Oh my god!” she exclaims. “A couple ambulances went past half an hour ago. That’s an awful stretch out there. Wrecks all the time. Bad ones.”

I ask if she’s heard anything about the people that were injured, but she hasn’t. She gives me a room for half price and even though it’s on Lindy anyway I don’t dismiss the gesture.

I take a long, hot shower and get dressed. I walk outside to the dumpster and toss my bloody clothes inside. Then I call Cody. The sun is setting and the steady woosh of cars off Interstate 75 mixes with the voices of travelers around me.

“Hey, Dad,” answers Cody after a few rings.

“Hi, buddy. How are you?”

“Pretty good. What’s up?”

“Well, you know, I just got the, uh, weekend off.” My voice is unsteady, all adrenaline now completely drained from my system. “You wanna go to the football game Sunday?”

“Sure,” he says. “Sounds good.”

“Alright, I’ll, um, try to get us some tickets and, uh, call you Saturday.”

A few seconds pass.

“Dad?”

“Yeah?”

“Are you okay? You sound kinda funny.”

All at once I’m afraid I might start crying. Hard. Like maybe I won’t be able to stop. I take a breath. “It’s been a tough day.”

“A bad one?”

“Yeah.” I press my fingers to my eyes. “Pretty bad.”

“You want to talk about it?”

“I do.” And that’s the truth. Still, I can’t. Not just then. “But I’ll tell you about it when I see you. Give you the full report.”

“Okay. Where are you, anyway?”

“Florida.”

Cody laughs. “Florida?! No wonder you’ve had a bad day. Florida sucks.”

I smile. “Yeah.” Then I hesitate, like I always do, a weakness inherited from my own father. But I make sure I get the words out: “Love ya, buddy.”

“Love you, too, Dad.”

I walk back to my room and lie down on the bed. I listen to the clock radio—the oldies station—as a patch of sunlight travels across the carpet. Then the room is filled with shadows, and finally it goes dark as Carole King sings me to sleep. Never once do I hear so much as a peep from upstairs.

The next morning I wake up starving. I have plenty of carbohydrates and a cup of scalded coffee at the continental breakfast and then I’m back on the road. It’s still early and I turn the radio on. Overnight there have been mass killings in three more countries. Suicide attacks. Car bombs. Retaliations upon retaliations. I think about the tragedies within those tragedies, the battles waged in individual lives, no less important because they go unrecorded. Could anybody’s god stand to bear witness to them all? I turn off the radio and get ready for a long piece of I-75. I give the rattling box truck a little more gas. I’m heading for home, the fighting over for now.

If you like this kind of thing, there's more HERE. And HERE. And HERE, too.

The photos were all taken over the last couple years with a WOCA 120G that does what it wants no matter how much Gorilla Tape I put on it.

The Homestead Act of 1862 was an attempt by the U.S. government to entice citizens to open up the West by offering 160 surveyed acres in exchange for a five-year commitment to reside on the property. Untold numbers of people who couldn’t afford their own farms and ranches or struggled at difficult factory jobs in crowded cities thought that sounded pretty good, and they quickly hitched up their wagons or hopped on a train.

This sometimes isolated and remote land was often accepted sight-unseen by would-be homesteaders and, while many did find fields fertile for farming, others did not. Some then tried to eke out a living as best they could; others got right back on the next train heading in the direction from which they’d just come. While the history of Dunlap, New Mexico doesn’t go back quite as far as 1862, it's in the homesteading spirit that those who settled here came to find themselves in this sparsely populated part of the eastern plains.

It was W.O. Dunlap who founded the town in De Baca County, about 35 miles southwest of Fort Sumner, and gave it its name. He scouted parcels for incoming homesteaders and a community developed. In 1907, a post office opened. However, as the years passed, many in Dunlap began to find it harder and harder to survive off this land, and most eventually left. Most that is, but not all. In fact, Dunlap persists as a small, close-knit rural community to this day.

The post office closed in 1961, possibly taking the general store with it. Now no evidence of either remains. And, really, it’s the lone building they once stood next to, the Dunlap Community Church and School, which was for many years the heart of this area. Worship, academic instruction, community discussions, and just plain-old get-togethers all happened in this little place on the prairie.

There's little documentation of Dunlap that I can find, and perhaps the best look back has come from a couple people who grew up there and shared their memories on the City of Dust Facebook page. I hope they won’t mind my including their words here and might even approve of this brief history of a place of which they clearly remain quite fond.

"Our ranch was the closest to the school. Once one of the teachers lived in our bunkhouse. Miss McCoy, I believe. My mother played the piano for all the plays and programs! No one's mentioned the dances! Hot times Dunlap!

“My family and our friends share a long memory of a uniquely close life in an isolated area but the memories of those times do not fade at all in my heart.” SS

“My family homesteaded and ranched in this area, and my grandmother, her brother, and my dad all attended school here. Dunlap was the hub of the ranching community. Dances and other social events were held in that building. It was a school, church, and community gathering place. There was also a post office and general store there.

"My grandmother used to ride her horse--or drive a horse and buggy--to the school. My dad, his cousins, and several friends all attended school there until they completed 8th grade, when they transferred to different high schools. My dad's last year there was around 1955. I last attended a church service there in the early 1980's, right before I left for college.” JDW

Some wonderful photos from 20 years ago, when the Dunlap Community Church and School was in much better condition (and still had the piano!), can be found at AT&SF in Roswell. I highly recommend taking a look. And I’m not just saying that because City of Dust gets a mention!

Thanks very much to JDW and SS for providing the kind of remembrances you can’t find through Google. If anybody else would like to leave recollections, please do so. Additional info for this post came from Robert Julyan’s trusty “The Place Names of New Mexico.” You can find a synopsis of a 1996 interview with W.O. Dunlap's grandson, Ralph, HERE. Finally, I should mention that the land on which the Dunlap Church and School sits is privately owned. Feel free to contact me if you would like further information.

Those of you who are fans of the Roadrunner and Wile E. Coyote might be excited to hear that there was once a town in New Mexico named Acme. However, the corporation which lent its name to the place made cement blocks not jet-propelled unicycles. In the early 1900’s, the Acme Gypsum Cement Company built a mill slightly south of the Clovis Highway (supplanted by present-day U.S. 70), 17 miles northeast of Roswell, where aliens would later badly botch a saucer landing.

In 1907, the Acme School commenced lessons from inside a tent. Later, a one-room frame and plaster school was built on the western edge of town, placed so as to keep the students away from the dust and smoke of the mill. Grades 1-8 were taught and kids had to bring their own books and supplies, along with their lunches.

Acme boasted a hotel, large horse barn, general store, depot, and some company houses for workers. Its post office opened in 1906 and closed in 1946, by which time the Acme Gypsum Cement Co. had been out of business for ten years. When the mill closed, it was estimated that there were 30-40 people in Acme, of which 20 were children. Now there is nothing left of Acme at all, except for the cemetery, which is north of U.S. 70, half a mile away from where the mill once crunched gypsum.

One hundred meters from what doesn’t remain of Acme is the photogenic ruin of the Frazier School. So close together that some people seem not to distinguish between Acme and Frazier, their existence overlapped slightly. Frazier was established later and survived longer...but not too much longer. Frazier’s post office opened in 1937, a year after the Acme mill closed. That same year the Frazier School was built. Funeral services were also held in the school since the Acme Cemetery was nearby. I assume that anyone who died in Frazier was also buried in the Acme Cemetery. I also assume funerals weren’t held during class, unless mortuary science was on the curriculum.

Now, Frazier was a community of folks trying to make it through the ongoing effects of the Great Depression as best they could. Many of those who worked at the Acme Gypsum Cement Co. had moved on and almost the only employment in the area was to be found in the dusty, meagre soil of the eastern plains. Some ranchers did have cattle, and one enterprising rancher is said to have herded turkeys as if they were sheep. Coyote skins could be sold at Bond-Baker Wool and Hide Co. for $1.50-$5.00 per pelt, and the meat of a cottontail rabbit might be worth $1.00. Still, many families lived in dugouts or other similarly challenging shelter.

Yet these homesteaders wanted their children to receive a good education. So, it was C.M. Martin, the Chaves County superintendent, who designated that a new school, larger than the one in Acme, be built on land donated by Otis L. Shields. Then Lake J. Frazier secured a contract with the Works Progress Administration for construction, and thus both the school and the community were named for him. This would be the last one-teacher school built in Chaves County.

Stones were gathered from the area for building material, and black volcanic rocks framed the windows and doors. White rocks were used to create a five-point star above the front doors, and a steer’s head with longhorns was set in the eastern wall. There was one double-size room with a smaller room on each side partitioned by double doors. There was no electricity, but six large north-facing windows let in lots of sunlight (see photo above). Nor was there running water, but a stone tower out back contained a cistern on top, as well as coal storage below. “WATER” was spelled-out in volcanic rock along the tower’s top (see photo below). Mesquite roots augmented the coal supply when it came to providing heat. Teachers were required to check the route for rattlesnakes before allowing a child to use the outhouse.

As soon as it was completed, pupils attending the Acme School moved to the Frazier School, as did their teacher, Margaret Harrison. There were 24 kids that first year and Mrs. Harrison boarded with the family of Mac Smith, who ran a store and gas station, as well as the post office. Some students walked to school, but those on ranches were picked up in a car. Horse-drawn implements were used to finally make roads suitable for busses. Mrs. Harrison had already moved to another school by 1938 and teachers came and went frequently in Frazier.

Frazier was an active community through World War II, but, after the war, enrollment in the school dropped below the mandatory eight pupils and it closed in 1945. Students in the area were then sent to Roswell. For a time the school was used a community center, but eventually even the need for that withered. Now, not a soul remains in Frazier and the ruins of the stone school, once the pride of many, are all that marks this place.

Most information for this post came from The last one-teacher school is special to many, in the December 27, 1996 edition of the Roswell Daily Record, as well as Acme’s heyday was from 1905 until late 1930’s, in the November 29, 1996 edition of the same. Both articles were written by Ernestine Chesser Williams and can be found in her collection, “Chaves County Schools 1881-1968: Treasures of New Mexico History.” The only place that has copies for sale is the Historical Society for Southeast New Mexico in Roswell. As usual, Robert Julyan’s “The Place Names of New Mexico” provided some detail, but Williams reported details available nowhere else.

Incidentally, Williams’ little homemade book seems to have debunked at least the location of the reputed Billy the Kid “croquet” photograph as her drawing of the original Flying H School looks nothing like the building in that photo. Pretty cool.

After last month’s epic 1,600 word post on the bayside ghost town of Drawbridge, California, let’s make some concessions to time and ADHD with a snack-sized post on the tiny dot on the map of eastern New Mexico known as Highway. Located on NM Highway 206 between Pep and Milnesand, perhaps 12 miles from the Texas line, Highway got its name because...well, it's located on a state highway. Locals will tell you it should be "Hiway," but NMDOT has other ideas. There isn't a post office and I don't think there ever was one, although there are a few inhabitants.

The building pictured above is probably the most prominent in Highway (or Hiway!), and was a welding and mechanic shop for many years. At first, the construction had me thinking it might’ve been a church or school. Oscar "Pouch" Lott lived and worked here most of his life and still maintains the reputation of having been the best blacksmith in the area. The precise function of the structure pictured below remains obscure, but if I had to guess I’d say it was something to do with water.

Hiway (or Highway!) is in Roosevelt County, and perched just inside the western half of that mighty chunk of high, flat tableland known as the Llano Estacado. You can read a bit more about this legendary feature in previous posts on the nearby towns of Pep, Causey, and House.

Everything I could learn about Highway came courtesy of Robert Julyan’s “The Place Names of New Mexico” and helpful viewers commenting on THIS post and THIS post on the City of Dust FACEBOOK PAGE.

Soon we’ll visit the twin ghost towns of Acme and Frazier, New Mexico, perhaps 50 miles southwest of here as the crow flies, and not too far from where that flying saucer crashed in Roswell.

My mother was the marshland. My father was the railroad. I was born in 1876 after they met on Station Island. Some now say that I am a ghost town, sinking in the mud. Maybe I am, but I hate the name. So do the people who remember. They remember the independent spirit, the close friendships, the happy days and their paradise that was lost. ~ Drawbridge

It’s rare that you find a fully abandoned, 100% ghost town in the midst of one of the most urbanized areas in the country, but such is the case with Drawbridge, California. Near San Jose and flanked to the north by San Francisco and Oakland, Drawbridge is rarely visited despite being surrounded by millions of people. In fact, I lived in Oakland and never even knew about it. The reason for its low profile is a good one; Drawbridge is located in a salt marsh and sinking further into the mud with each high tide. It is also part of the Don Edwards San Francisco Bay National Wildlife Refuge, which is home to several endangered species and thus closed to the public. The refuge is patrolled by US Fish & Wildlife Service personnel, who I encountered on my trip while they were trying to apprehend some other “visitors.” Why didn’t I get busted? Because, through leveraging my vast City of Dust empire, I received legitimate access and could thus arrive via boat instead of taking the illegal and dangerous route.

Like so many other ghost towns, Drawbridge was brought to life by trains. In 1876, the South Pacific Coast Railroad built a two-room cabin for a bridge tender, Mr. Mundershietz, on a new stretch of line that by 1880 would link Alameda to Santa Cruz. The cabin was deep in marshland, between Coyote Slough and Warm Springs Slough, on a chunk of relatively solid ground soon known as Station Island. Because the train would stop at Station Island, people could now get there, and because there were lots of ducks around, it was hunters who first wanted to get there. The railroad even provided an old baggage car and chair car as free accommodation for hunters.

So it was that the earliest buildings in Drawbridge were gun clubs, and there were many of them. The first structure, after the bridge tender’s cabin, was the Gordon Gun Club, probably built in 1880. Incredibly, given the transience of wooden buildings in Drawbridge, I believe its ruins are captured in the b&w photo above, based on a shot from the 1980's, when it was still easily identifiable by its rounded Dutch roof and square nails.

After the Gordon Gun Club came The Sprig Duck Club, The Widgeon Gun Club, The Twilight Gun Club, The Tony Gun Club, and cabins with names like the Precata, Recreation, Harbor View, Sorry, Don’t Worry, Clambake Club, Julie Lodge, and more. As Drawbridge was often reached by boat, boat-building and repair was another typical pastime, as were swimming and fishing, naturally.

Some people actually lived in boats, known as “arks,” which were put up on pilings. One was a 50-person Matson Line lifeboat that had a cabin built in top of it. Drawbridge’s structures, all on pilings to stay dry when the tide came in, were along the railroad tracks, which became known as “Main Street” or “A Street.” Walkways were extended from front doors straight to the tracks, a privilege for which the railroad charged $1 a year. There were also “high tide parties,” when foot paths were flooded and neighbors would visit each other by boat. Toilets, unfortunately, went right into the marsh.

In 1902, the Sprung Hotel was established. As many as 500 people would come to Drawbridge each weekend, and Mrs. Sprung would often rent her own bed and sleep in the bathtub. In 1920, with the arrival of Prohibition, she made homebrew for 25 cents as quart, as well as wine. The Hunter’s Hotel was built by Louis Demit, also in 1902, and later run by his wife, Susan. Whether Louis died or the couple divorced is unknown. Despite being smaller than the Sprung, the Hunter’s Hotel had a large ballroom decorated with stuffed birds and windows all around. It also contained a baby grand piano.

As one man familiar with Drawbridge, William McCall, Sr., said, “You wouldn’t go down there if you weren’t a different breed of cat. It wasn’t the easiest place for access; every duck you got you worked for. And like those people that went down, they were in another world. They were completely away from civilization.” Or, as the last resident of Drawbridge, Charlie Luce, put it, “…it wasn’t a disease, that Drawbridge mud just calls to you!”

By 1926, about the peak of Drawbridge, there were 90 cabins and five passenger trains coming through each day. Later, rumors circulated that Drawbridge was filled with gangsters, gamblers, and prostitutes (with a roulette wheel at the Hunter's Hotel to decide which lady of the marshy night would be yours!), but it was mostly populated by doctors, dentists, and store owners, many with a passion for duck hunting. Even so, mothers on the north end of the island warned their children to stay away from the south, while the south considered the north “stuck up.” By the way, there really was a roulette wheel, but residents said the only thing wagered on was waterfowl.

Then Drawbridge began to sink more quickly as the surrounding sloughs were cut-off by dikes or drained. Wells for fresh drinking water had to be drilled deeper. Sewage from Bay communities began to foul the water around Drawbridge, and the ducks decided it was time to leave. Next the Great Depression arrived and, after that, vandalism. Newspapers began referring to Drawbridge as a ghost town, with cabins full of antiques simply left by their owners. This was not true, so signs were hung on cabins: “Please don’t shoot my house,” and “Dear thieves and vandals, Please do not break into this little house. It’s the only home we have.” Sadly, the signs didn’t always work.

The Sprung Hotel closed in 1930. It would finally collapse in 1968. Hunter’s Hotel burned in 1943, possibly from a spark off the cigar of then-owner, Barney Panella. So Barney constructed the only two-story building ever seen in Drawbridge on the site, complete with another ballroom and yet another baby grand piano. It would burn in 1984. Throughout the history of Drawbridge, fire has been perhaps the gravest danger, even surrounded as it is by water.

By 1940, only 50 cabins remained and the marsh was so polluted it could not be swum in. By the end of the decade, the sloughs were too silted-in to navigate. The years passed and there were more fires, some thought to be for insurance pay-outs. The train no longer stopped unless it was flagged down. In the 1960’s, partiers began to make the trek to Drawbridge. Some of these people, called “dopers” by residents, would try and stay in empty cabins only to be chased out with a shotgun or an ax. In 1970, the railroad station was torn down.

Yet some old-timers held on, until at last there were two. Nellie Irene Dollin, who had first come in 1910 and bought a place in 1932, left in 1974. Her house was broken into by two drunken kids one night while she was home with her granddaughter. She had no more trouble after firing her shotgun out the window, but the newly-christened “Shotgun Nellie” had had enough and moved to nearby Hayward. Charlie Luce visited Drawbridge in 1930, but didn’t go in on a cabin—The Sunset Club—until 1950. It was torched in 1964. Charlie and some friends bought another house and he began living in Drawbridge full-time with Quincy, his dog. He was bought out by the US Fish and Wildlife Service in 1979. His former home burned down in 1986.

These days Drawbridge is almost more liquid than land, a condition that will only accelerate as the rate of sea level rise increases. Everyone on this trip left wet, muddy, and cold…but happy. One iPhone was submerged (while in a hip pocket!), but at least no one drowned. People are still trying to have parties, too, and continuing to damage or destroy buildings, but now they're usually getting caught before the party even gets going. While it might appear that there are a lot of structures remaining, compared to what was here 20, 30, or 40 years ago there is relatively little. Hopefully, what's left will persist until Mother Nature fully reclaims what was once hers alone, and the ghost town in a salt marsh finally vanishes entirely into the mist of the San Francisco Bay.

Many thanks to the DESFBNWR USFWS for very graciously letting me access Drawbridge. The public (which also includes me, now) is asked to please obey the "No Trespassing" signs. That's the best way to protect Drawbridge and honor its history. A special thank you to D. Thomson for providing a boat and navigation skills and generally making it all happen. Virtually all information from this post came from "Drawbridge, California: A Hand-Me-Down History" by O.L. “Monty” Dewey. If only every ghost town had such a thorough and well-researched oral history written about it. Thanks again, D.T.!

Next time we’ll be back in New Mexico, but just where is a mystery to me as much anyone. Oh, and happy birthday to me! Finally getting a new City of Dust post up is a pretty good present to myself.

This month I'd hoped to finally finish a piece on Drawbridge, California, the ghost town in a salt marsh, but time has moved too quickly. So, rather than let City of Dust go dark for all of November, I thought I'd post this tale. While it contains no ghost towns or historical content whatsoever, it does feature the desert as a main character. The photos were taken earlier this month, mostly in Salton City, on the west shore of the Salton Sea, in the Colorado Desert of California. However, the last two shots are from the South Bay Salt Works, the second-oldest continuously operating business in San Diego, CA. See you in December!

THE REAL DESERT

I’m spending a few days out in the desert again. I can’t tell if I’m moving towards something or moving away, but that’s nothing new. Whatever the case, I’ve got some time and a little bit of money so I’ve based myself out of the Whispering Sands Motel, and each morning I set off in a different direction down some desolate, windswept two-laner.

Sometimes it can be hard to find food out here and when I pass a pizza place in what looks like a wooden shack I make a u-turn, park the rental car in about five inches of sand, and go inside. They’ve got some pretty fancy slices for the middle of nowhere and the twenty-something girl behind the counter in Daisy Dukes, tank top, and tattoos seems genuinely thrilled to tell me that the caprese has been drizzled with locally-sourced balsamic vinaigrette and the Greek has real Kalamata olives. This country seems to not actually make things anymore, so I guess we’re going to see if we can float an entire economy on craft beer, pour-over coffee, medical marijuana, tattoos, and artisan pizza. Still, the slices look good and I get one of each. The girl hands them to a large, sweaty guy in the kitchen who pops them in the oven. His tattoos look like they probably cost less than hers and didn’t take nearly as long, either.

There’s no one in the dining room except for five guys in the back who have brought in a couple of their own six packs. They’re discussing “bands that are popular but not super-popular,” and, thankfully, I haven’t heard of most of them. But even so I quickly understand that they have bad taste. I grab a copy of “Sunrunner: The Journal of the Real Desert” off the rack by the door. The subtitle seems a little audacious, but there’s a story about a highway that sounds even more godforsaken than the ones I’ve been traveling. Thus, they get my attention.

The girl brings my slices out on paper plates and starts talking to the guys. At first it seems like maybe they all know each other and she asks them what kind of music they want to hear. I instantly wish she wouldn’t have.

“Do you like Zeppelin?” she says, when, happily, no one suggests anything.

That doesn’t sound terrible to me, but I guess I don’t get a vote.

She flips through her phone for a few more seconds. “How about Glen Campbell?”

Given the surroundings, that sounds better, if stranger. Don’t kids have their own music anymore? This stuff wasn’t even my music.

More silence. “Who?” asks one guy, finally.

“You know, ‘Just like a rhinestone cowboy...,’” sings the girl, only a touch out of tune.

The guys erupt in laughter, one louder than all the others, naturally.

“Nah, nah,” the loud one says, shaking his head and taking a pull off his beer. “I’m good.”

Then another suddenly looks intently at the girl. “Play your favorite song,” he says. “What's your favorite song of all-time?”

The girl is quiet and, after some obvious thought, replies, “That’s hard. That’s maybe something I’d tell somebody after we’d been together for, like, three months.”

The guy raises his hands in front of him, palms up. “What? Don’t we know each other well enough now?”

The girl takes a step backward toward the kitchen just as the guy’s phone rings. He answers, listens for a moment, frowns, then says, “I’m with the bro’s,” and hangs up, much to the amusement of his friends. It’s getting hard to focus on the story about the highway, but it seems to pass mainly through towns named after scientific elements, which is always a good sign.

“No, seriously,” says this guy, starting up again. “Play your all-time favorite song. Let’s get to know each other better.”

“I don’t think so.” The girl takes another step toward the kitchen. “It just seems, like, too personal to me.”

Now the guy lowers his voice. “Come on. I could learn some things about you that are more personal than that. Why don’t you let me? Then maybe you’ll play me your favorite song, too.”

His friends laugh and drink as the girl turns quickly and goes into the kitchen. I can hear the chef talking, but can’t make out the words. I take a few last bites of my balsamic-drizzled caprese, grab my Sunrunner Magazine, and step out the door into a blinding wall of heat and sun.

After a couple dozen miles I decide that I need a palate cleanser and stop at an AM/PM. Spending lots of time in the desert makes me crave salt, so I usually buy Payday bars. But this time I go for a Skor. As I’m reaching down for it a black man comes right up next to me and leans over, too. “Gotcha a little sweet tooth?” he whispers, almost in my ear. This is startling, but the man smiles at me so good-naturedly that as we both straighten up I’m disarmed. He’s wearing a filthy t-shirt and swaying. He seems a little drunk.

“Yeah,” I reply, also whispering, feeling conspiratorial for some reason. “Sometimes I just need a little dessert.”

He grins and blinks his eyes in a funny way before going into his pitch. “Hey, man. You don’t have maybe five dollars I could borrow for gas, do you?” He gestures weakly towards the pumps where he surely has no car. Or truck. Or ATV, for that matter. But I like this guy more than the bro’s, so I give him a dollar, trying to not draw attention from the cashier, who is looking warily in our direction. I tell the man to take care. He tells me to have a nice night and seems to really mean it.

Outside the sun is beginning to set over the spiky mountains, yet it somehow feels hotter. I don’t know how that happens in the desert, but every now and then I notice it. Maybe it’s just my imagination. I’m planning on doing a little off-road exploring the following day, but I didn’t bring any sunscreen and, despite my fondness for blast-furnace landscapes, I really hate suntans. A sunburn seems an affront to myself perpetrated by no one but me, like spitting in my own face. So I drive further into this little town, the softening purple-blue horizon thick with mountains, reminding me why I’m out here in the first place. I begin looking for a drug store.

The first place I come to is Wal-Mart, of course. But they tend to put me in a bad mood. Since I’m pretty much already in a bad mood, I press on. Next, oddly enough, is a K-Mart. Where America shops. The red-headed stepchild to Target’s good son when I was growing up. K-Mart’s seem increasingly rare and I find no reason to ask why as I wander the ravaged shelves under brutal fluorescent lights with a handful of other spaced-out-looking customers. Finally, I find Health and Beauty and choose my protection.

Back outside it’s getting dark and as I head to my car another man sees me across the sand-strewn parking lot, sunscreen swinging in the plastic bag at my side, and begins to walk quickly over. I can feel the heat radiating off the asphalt as I slow down and then come to a full stop. I decide to wait because the man is wearing broken-down cowboy boots with thick, dingy green sweatpants tucked into them. He’s also got on a vest that looks like something a Boy Scout might have made, covered in patches and badges, and cut crudely out of a dark felt material. Underneath the vest he’s bare-chested, his skin the tone and texture of old leather. Finally, he’s sporting a crumpled, sweat-stained, black Stetson, but it’s too large and sits too low, barely above his eyes. As he approaches, he pushes the hat up.

“Hello, sir. Could you spare any change for a burger?”

My curiosity is probably obvious. “Isn’t it a little hot for sweatpants out here?”

The man laughs with seemingly genuine mirth and strikes a pose. “I’m a…a…a…”--he waves a hand theatrically, searching for words--“cock-eyed cowboy.” Crossing his ankles he tilts to one side and then seems to almost curtsey.

I tell him he’s got an interesting look.

“Thank you,” he replies, nodding his head. “Everyone wants to be interesting but nobody wants to pay the price. Me? You can see I paid the price. I may have even paid too much.” He laughs again. “All I can afford now are some ratty-ass sweatpants, a vest I found in a box, and a hat that’s too big for my head.”

I like this guy best of all and give him whatever cash I have left, which turns out to only be $3.72. We wish each other well and go our separate ways into the still desert night, the stars blinking on one-by-one overhead, the waxing yellow moon just clearing the jagged peaks, bathing us both in a gentler kind of light.

But soon enough the warring sun will rise again, and back at the hotel I tell the manager I’ll be checking out the next day. I take my copy of Sunrunner up to my room so I can read more about that highway I’ll be driving in the morning.

Let’s stay in central New Mexico for one more post and add yet another piece to the picture of a region that in the 1920’s was the country’s largest producer of pinto beans. While you probably aren’t going to drive through without reason, as you might Mountainair, nor are you going to find it in most ghost town guides, as you will Claunch, Cedarvale was an important dry land farming and ranching community from the time of its establishment in 1908 until the Dust Bowl and Great Depression combined, along with overgrazing and farm consolidation, to force many of its residents to search for their fortunes elsewhere…yet again.

It was Ed Smith, William Taylor, and Oliver P. DeWolfe who chose the site for Cedarvale and requested that it be surveyed by the U.S. government. The town would be along the route of the New Mexico Central Railroad. Lots were sold through the General Land Office and a post office was soon opened. The new place was named Cedarvale after Cedar Vale, a town in Kansas from which the founders hailed and was also located in a valley with cedars (i.e., junipers).

Soon hundreds of homesteaders from other states arrived on “immigrant trains,” following the lead of Smith, Taylor, and DeWolfe. Most were looking to plant pinto beans. The relatively high altitude (6,384 ft) and short growing season of central New Mexico was good for the beans, which could be dry farmed and were in demand, particularly once World War I began and pinto beans were used to feed soldiers. Come fall, the harvest was stored in Cedarvale’s three elevators.

The population of Cedarvale would eventually reach about 500, but is now perhaps half that, and there are no functioning commercial concerns. The post office closed in 1990. But what impresses one most as they approach from the northwest along Highway 42 is the looming wreckage of the Cedarvale School. Initially, the school in Cedarvale was a typical one-room affair, but as both the town and Torrance County grew more space was needed. So, Oliver DeWolfe donated 20 acres of land and, on August 25, 1917, the Torrance County Board of Education approved a bond issuance in the amount of $5,000.00 to construct a new school.

The school was finished in 1921 and an addition made in 1935 via the Works Progress Administration (WPA). By then, the building seems like it would've been surprisingly big for the area, containing four large classrooms, each of which contained three grades and about fifty students. Children attended kindergarten through eighth grade and were then driven in the back of a truck a few miles southeast to Corona for high school. No fancy Bluebird busses here!

Aside from continuous and dire warnings about rattlesnakes, the massive gymnasium remains perhaps the most striking feature of the Cedarvale School. This was clearly a gathering place for the entire community, as well as a basketball court (complete with raw wooden backboards still in place) and, judging from the design, probably a theater. I’ve heard it hosted some bingo games, too. Despite taking the warnings fairly seriously—signs are even painted on the walls of the school—no rattlesnakes were encountered on this trip.

The school closed in 1953 and is now falling down quickly, the years finally overcoming its sturdy construction. The large wooden beams are impressive, and I’m told the Cedarvale train depot was built to the same hardy specifications. The depot no longer stands, but the materials were re-purposed and used in a home in Albuquerque which is owned by the daughter of a man who helped build both the depot and the school. I’m pleased to have been able to walk around on that historic lumber recently!

There are still many people that have fond memories of growing up in Cedarvale, as is true for virtually all the small central New Mexico towns in which the train once rattled through constantly and the whoosh of pinto beans pouring from the elevator heralded the end of one season and the approach of the next. These are sounds which may yet perhaps be heard, if only faintly, in the startling quiet of places like Cedarvale.

As I said, there ain’t much out there on Cedarvale. David Pike’s “Roadside New Mexico: A Guide to Historic Markers” has a good synopsis of the town’s founding and the history of the school. You can glean a little bit more from “The Place Names of New Mexico” and its similarly-named predecessor, “New Mexico Place Names: A Geographical Dictionary.” Beyond that, you’ll have to hope that maybe someone that was there will tell you what it was like.

Of all the places we could go from long-lost Centerpoint, New Mexico, which we visited last time, perhaps it makes the most sense to simply continue south down Highway 55 and follow it through a few sharp turns until we get to Claunch, something less than 30 miles away. Claunch’s position in central New Mexico put it firmly within the pinto bean empire of the early part of the 20th century, when neighbor Mountainair was proclaiming itself the “Pinto Bean Capital of the World” and soldiers fighting in WWI were eating beans that had been grown in the fertile Estancia Valley.

Back around 1900, when Claunch was being settled, it wasn’t known as Claunch. Instead, it was called Fairview. Or perhaps DuBois Flats, after Frank DuBois, a local cattle and sheep rancher. Or maybe it had been called both. I can find no certainty on the matter. (UPDATE: Claunch was formerly known by both names, with DuBois Flats the earliest, dating to the 1890's.) Whatever the case, Claunch became Claunch near 1930, when the town was big enough to warrant its own post office and a DuBois, NM already existed. Or a Fairview, NM existed. Or both did. But a new moniker was definitely needed and L.H. Claunch, who ran the nearby Claunch Cattle Co., agreed that his surname could be used for the town. Later, he would firmly refuse to let his name be attached to the Claunch Saloon, which thus never opened.

Claunch flourished in the 1910’s and 1920’s, before it was actually called Claunch. However, by the early-1930’s, just as Claunch had gotten its name and post office, the Great Depression and the relentless drought of the Dust Bowl began to hit farmers in the Estancia Valley hard. Within a few years a Works Progress Administration (WPA) school would be built, but as more topsoil was carried off by the howling prairie winds it was already becoming too late. The school closed in the 1950’s, but its skeleton yet sits on the plains.

Where it's been said that there was once a homestead on every 640-acre section in the area, by the late-1960’s it was more like one homestead for every 20 sections, and only six or eight close-knit families inhabited Claunch. These are numbers which have certainly not increased in the last 50 years and the place remains isolated, the nearest towns, as ever, being Mountainair, 37 miles northwest, and Carrizozo, 42 miles southeast.

While Claunch is largely quiet these days, if you listen closely you might hear voices on the breeze, for singing once echoed loudly across the gravel roads. At first, there were gatherings in people’s homes, but then, in 1916, under a brush arbor not far off from town, the Torrance County Singing Convention was born. These were not informal get-togethers, but true events rooted in long religious tradition stretching back to the remote forests of New England in the 1700’s. Ralph Looney, relating his attendance at a convention in Claunch in “Haunted Highways,” even describes learning of shape-notes, a tool intended to aid those who can’t read music, which has a rich history in a unique type of hymn singing in the Deep South often referred to as Sacred Harp.

The Torrance County Singing Convention attracted people from all over the region and even those from other states who had moved away. A yearly state-wide convention could bring in as many as 1200 singers. In DuBois Flats/Fairview/Claunch, the singing convention “year” began on the fourth Sunday in April, with another convention held in June, August, and October. And, as with Sacred Harp “sings” in the South, food--and lots of it--was required to sustain hours upon hours of music in which everyone participated. So, after two hours of singing in the morning, it was time for lunch.

Ralph Looney describes a spread he saw in the mid-1960’s, years after one might’ve assumed Claunch was forgotten: “Meat loaf, fried chicken, roast chicken, ham, beef roast and pork roast. Turkey, molded fruit salads, slaw, tossed salads. Vegetables like pickled beets, green beans, wax beans, mashed potatoes, potato salad, candied yams. Homemade yeast rolls and cornbread. Chocolate cake, angel food, vanilla cake, white cake, apple pie, cherry pie, blueberry pie and so on and on and on and on.” Then would follow at least another three hours of songs such as “Joy is Coming,” “Then We’ll be Happy,” and “When the Roll is Called Up Yonder.”

I’ve been assured there is still fine music being made in Claunch, if not on quite so grand a scale. And the post office is open yet, and operating as a library, too. You can check a book out or swap for one of your own. But as you walk past the old pinto bean elevator, with Ye Olde Dance Hall still faintly visible on the front, and a sign for a museum which it’s probably best you not wait too long to open, it is the past you feel, remarkably soothing--which is not always the case in such places--and somehow alive and singing.

It is perhaps worth adding a short postscript: Claunch lies about 40 miles northeast of the Trinity Site as the crow flies. Given prevailing winds on the morning of the world’s first atomic bomb blast, it was directly in the path of potential fallout. People from the region still talk of cows that turned white after the explosion and were then shown off at local fairs as curiosities to ponder over. But it’s cancer that may be the longest-lasting local legacy of Trinity, and while a group calling themselves the Tularosa Basin Downwinders Consortium has spent years fighting for recognition and compensation, it could be too late for Claunch, whose population is now under 10, the old-timers gone, their families scattered long ago. It's a strange and unsettling footnote in the history of the little town of pinto beans and singing conventions.

Ralph Looney’s “Haunted Highways” provided a wonderful description of Claunch in the 1960’s, while “Ghost Towns Alive” by Linda Harris revisited the town over 40 years later. I grabbed a little info from Robert Julyan’s “The Place Names of New Mexico,” as I tend to do, as well.

Next time we’ll just see where we end up. I’ve got a backlog of locations that only seems to grow larger.