(CONTINUED) Nineteen

“Dane was always a little haunted after that, I think.”

Mary and I were seated at her dinner table, a dark, heavy piece made of thick wood that could’ve been 400 years old for all I could tell. We were eating enchiladas made with freshly mashed pinto beans and hot green chiles. Just before serving Mary had topped each of our plates with a fried egg. The food was delicious. The conversation, however, had quickly become morbid, reminding me of my own roiling hell. Mary went on: “Although, I don’t believe there was any reason for him to blame himself for Oscar’s death.”

Almost immediately after sitting down Mary had begun to tell me how wonderful it was to once again have some company at the dinner table. This led to a description of her late husband’s long battle with cancer and, working backwards in time, she’d now arrived at the point when Oscar, their only child, had hung himself from the garage rafters at the age of 15.

“So tell me, Mr. Gould, what are your thoughts on suicide?”

I put down my fork and wiped my mouth with my napkin. The truth was, I had thought about suicide a fair bit over the last few days and maybe even for longer than that. At times I’d probably even thought it a pretty good idea. “Please, call me Tom,” I said, and then drank some wine. I didn’t know what to tell her. I could look at it philosophically; I could discuss it from a religious point of view; I could describe the torments of countless artists--some of whom I’d known--and their desire to end a ceaseless pain. It was all bullshit. “I don’t know that I have any thoughts on suicide,” I finally replied. Mary looked at me strangely. For a moment I thought she may have smiled. I continued: “Or, I should say, I don’t have any thoughts on the suicide of others. I don’t believe we can blame a person for taking their own life. And don’t I believe anybody should blame themselves because someone they know has taken their own life.”

“Even one’s child?” Mary asked.

I paused. This conversation with my new landlord disturbed me. “I suppose it’s impossible for a parent not to blame themselves. But some people just get wired wrong, I guess.”

She refilled my glass. “So, you think a predisposition for suicide is genetic?”

I did indeed, but I wasn’t sure I should say so. I felt like I was taking a test that I’d better pass, even though I didn’t know what the penalty would be for failing. I began to say something, stopped myself, picked up my glass, put it back down, and finally said, “Maybe.”

She was quiet for a few minutes. I went back to my enchilada and hoped that I’d heard the end of the topic.

“But what about your own?” Mary had hardly touched her food and it was growing cold. Now she was staring at me intently.

“Excuse me.”

“What are your thoughts on your own suicide?”

I just looked at her, holding the fork in midair.

“I was just wondering. You said you didn’t have any thoughts on the suicide of others. I was just wondering if you had any thoughts on your own. Would you ever take your own life?”

I put the fork back down. I looked directly at her. “No, I wouldn’t.”

“Can you be so sure?”

I’d just turned back to my plate and put the last bite of enchilada in my mouth. I nodded while chewing: “Yeah, at this point I think I’m pretty certain of that.” I knew I was finally telling the truth, but there was no satisfaction in it. Mary started to ask something else and I put out my hand. “Please, can we not talk about this anymore?”

She laughed loudly and I was a little startled. “I’m sorry,” Mary said. “I thought all writers liked to talk about these things.” I couldn’t tell if she was making fun of me.

“No,” I replied. “We just like to write about them.”

Mary laughed again and stood up. “I’m just an old woman and I think about death too much. You don’t worry about it much when you’re younger.”

I knew that wasn’t true, but I wasn’t about to get into it.

Twenty

That night I went to bed in what had probably once been a guest room. It was off the hallway on the second floor and had a dresser, desk, and queen-sized bed. The bed was the most comfortable I’d had since well before showing up in San Francisco to sleep on Ruben’s couch. Even so, I didn’t sleep much more than two or three hours. I would’ve been surprised if Mary had slept anymore than me. Throughout the night I heard her padding down the hall. I heard the stairs creak as she went downstairs. I heard her mutter to herself as she came back up. At one point I thought I heard a radio go on. We were a fine pair.

In the morning I laid in bed and listened to Mary make herself breakfast. I felt like my life had been cleaved in two. Everything that had happened up until the time I’d arrived in Santa Fe belonged to one person and everything since was something different, without history or precedent. I knew it was only an illusion but the sensation was so strong it made me feel like I was losing my grip on reality. On the other hand, it was this very break that made it possible to function at all. What’s more, the things I was doing and the situations I was finding myself in did not seem to be without meaning. I had woken from a nightmare into a dream.

I heard the door shut as Mary left and once the sound of her car had faded down the road I got up. I went downstairs and there was cereal, fruit, and bread arranged on the table. A note was nearby: “Tom, please help yourself to anything you want. Juice is in the fridge and the coffee maker is ready to go. Just turn it on.”

I flipped the coffee maker on and sat down at the table. It really was like a dream. Then I remembered something. I went back upstairs and checked my phone. There were two calls from Ruben and one from my agent. It had been a long time since I’d heard from my agent. Ruben’s message was first: “Tom, I know you didn’t kill Ann. But you have to do something. It’s on the news. They’ve got your name, your picture. You have to come back. That guy killed your wife; people will understand.” I doubted that people would understand. The message from my agent was next: “Tom, what the hell…” He was already out of breath, almost screaming. I hit delete. The last message was from Ruben but there was nothing and then a beep. It didn’t sound good. I changed my outgoing message to: “You’ve reached Tom Gould. Please leave a message.” This was mostly in case Julie tried to call. I had no intention of ever answering that phone again.

I went back downstairs and had some coffee and a banana. The banana was hard to eat and the last few bites almost made me retch. I brought my coffee upstairs and took out the notepads and pens. I sat at the desk and looked at them. From memory I began to write out a short story by Chekhov about a man who takes shelter from the rain under an upturned boat on a beach. When he crawls inside he sees that a young woman has also taken shelter under the boat. At first they are shy and tentative and speak only with hesitancy and brusqueness. But soon the man hopes the rain might never stop. When it finally does neither seem to want to leave the shelter of the boat, but finally the woman tells him she must get back home. She crawls outside. The man remains under the boat for awhile longer, feeling that something very important is being lost through nothing more than his own willful rejection of it. He does not move. At last he comes out into the early twilight. He does not even know the woman’s name. He will never see her again. Perhaps his life has been ruined. At least, that was the way I remembered it. What I couldn’t recall I made up. I left the notepad on the desk and hoped that Mary wasn’t too familiar with Chekhov.

I spent the rest of the day walking around town, wondering if my fate was being decided for me at that very moment some 1200 miles away. I wondered if it was only going to be a short time before someone showed up in Santa Fe for no other reason than to find me and bring me back to San Francisco to stand trial for murder. Or would they make me stand trial for two murders? Or three? Every time I sat on a bench or went into a café I began to expect the inevitable hand on my shoulder. “Mr. Tom Gould? You have the right to remain silent.” I thought about running but there was nowhere else worth running to. It was like I’d suddenly found a home, entirely unexpectedly and undeservedly. If it wasn’t going to last for long I was going to try to forget about both the past and the future and live only for the moment, the only thing that wasn’t run through with dread and regret.

At 5 o’clock I walked into the Golden Horse. I said hello to Mary, who was sitting at a desk by the door, and, though I had not told her that I would be stopping by to meet Julie, she said, “Just a second. I’ll go tell Julie you’re here.” It made me apprehensive to know they might be talking about me, but it also made me smile. Worse things were being said about me at that moment, of that I was certain.

Julie came out from the back wearing a kerchief on her head and holding a tape measure. “I was just framing a new piece. I’ll be out in a second.”

I browsed around the gallery, a man who days before had held his ex-wife in his arms while she and their baby died; a man who had beaten another man to death with a poker; a man who was a fugitive from the law; a man waiting to take a girl he barely knew out to dinner, to bring her into his life. Yet I felt powerless to do anything else, to change the fate I was moving toward. My life was no longer my own.

“Okay, let’s go.” She’d come up behind me and put her hand on my shoulder. I actually jumped off the floor. She stared at me, eyes wide, bemused.

“I’m sorry. You startled me. I was so absorbed with this piece.” I gestured toward the painting, a poorly-wrought oil painting of an adobe church.

“Really?” asked Julie. “I’ve never thought much of that picture. It’s been here for ages.”

I had no response, so I said, “Well, I guess art is in the eye of the beholder.”

Julie laughed and I followed her out the door. “Where are we going?” I asked, as we walked down Canyon Road.

“The Pink Adobe.”

Now I laughed. “Rubbing it in my face, eh?”

“On the contrary. I thought it would be cute.”

I hadn’t been certain if this evening was meant to be a date or not. To be honest, it hadn’t really mattered to me and I’d given it little thought. But now I was certain and it did matter to me. But I wasn’t really sure I wanted it to be a date.

Julie talked about her day as we walked and I said that I’d written a story and immediately regretted lying to her. She asked me what it was about and I took a deep breath and repeated the Chekhov tale. I was relieved when she told me she thought it was beautiful, but I knew it was a bad start to the night.

Inside the Pink Adobe it was dark and we got a small, rickety table in a corner. A little light came in through a curtained window farther down the hall, but our table was mostly lit by a single candle. Julie looked gorgeous by the flame, her grey eyes seeming a little sad even when she smiled. She pulled her hair up and had even put on a little lipstick; I hadn’t noticed that when she’d surprised me at the gallery. I started to hate myself again.

“So,” she began, “are you originally from San Francisco?”

“No, I’m from Boston, but I moved to San Francisco many years ago.”

“Where does your family live?”

This was going to be difficult. I didn’t know if I should lie or tell the truth or simply mix the two together as seemed convenient. I spoke the truth and lied by omission: “My parents are dead. My father got lung cancer from working with asbestos—he worked construction—and died in his early fifties. Without him, my mom went pretty quick. I’m an only child and we never really got together with any of my other relatives when my parents were alive.” The waitress brought us our menus and two glasses of water.

“An orphan,” said Julie.

“Yeah, I guess. Not a very happy tale, eh?” I didn’t want her to ask a follow-up, so I said, “And you?”

She smiled. “Santa Fe, born and raised. I’ve got a younger brother, which you know, and my mom lives nearby. I never really knew my father. He left when I was pretty young. My brother had just been born. Not a very happy tale either, huh?”

“Family stories rarely are.”

We took a few minutes to look at the menus and when the waitress returned I ordered huevos rancheros and Julie had a vegetarian burrito. We went back to small talk for a bit and then Julie stopped and looked at me sort of funny and grinned. Then she said, “Mary thinks you’ve been married.”

My stomach dropped. I searched for a word, any word, really, but could say nothing. All at once I missed Ann so badly I thought I might start weeping. Julie must’ve noticed something was wrong because she started to apologize.

“It’s okay,” I finally managed to say, though it was not okay.

For a while we were both silent. It seemed like there was nothing else to say, like there might be nothing else to say between us ever again. I searched for words and said the first sentence that managed to cohere: “So, are you seeing anyone?”

She looked at me, slightly bewildered. I knew immediately that it was a stupid thing to have asked.

“No,” she said. “I was seeing this guy a couple months ago but I ended it. He was really boring in bed and I’m up for just about anything.”

I felt embarrassed and as she started to go on I held up my hand. “This kind of talk makes me uncomfortable.”

“Why?”

I looked at her, lit by the candlelight, worrying an earring. I wouldn’t think of laying a hand on her. “Because, you’re so…so…”

“So what?”

“So young.”

Her eyes got wide and then she leaned back and laughed so loudly that diners at the three nearest tables all turned to look at us. When she could finally speak she said, “Tom, how old do you think I am?”

I gestured vaguely. I found I couldn’t even offer a guess.

“I’m 28,” she said. “I’ve been drunk, had sex, smoked pot and even”—she gestured at her left ring finger with the thumb of that hand—“been married and divorced.” She laughed again. “But thanks—that was sweet of you.”

I’d often made this mistake in my life; taken beauty for innocence. But beauty untested, untried, was not beauty at all but simply weakness waiting to be devoured. That which would be beautiful must know ugliness, despair, hatred, and pain and then, only once submerged in the flames of the world and risen again, can it appear as true beauty. Thus, beauty is never for the young. I was so embarrassed I blushed and hoped that, in the darkness, she could not tell.

Julie laughed some more and wiped her eyes and asked me how old I was. “Thirty-five,” I said, “going on 80.”

The waitress brought our food and we ate quietly, talking every now and then about childhood memories or trips we’d taken. Julie began to talk about her Catholic upbringing and how important religion had been to her mother. She said that she still prayed all the time and asked if I ever did.

“As a boy I prayed hard for just one thing,” I said. “But I haven’t prayed since.”

“So your prayer wasn’t answered?”

I smiled a little and shook my head.

Julie took a bite of her burrito and chewed it slowly. Then she said, “I think that just because you’re prayers aren’t answered doesn’t mean you shouldn’t keep praying.”

“Is that faith?” I asked.

“Some people might call it that.”

I smiled again. “Some people might call it something else.”

She looked away quickly. I’d made her angry. I tried to make amends: “Hey, I just said it might be something else. I didn’t say I thought it was bad.”

After our meal we walked around in the cool desert evening. The moon hung full in the sky and everything was bathed in the milky light. The air was so soft you could hardly feel it on your skin, a night that could only be had amidst sand and rock and the endlessly unspooling sky. For a time we sat watching the black water of the Santa Fe River flowing slowly through town. Then Julie stood, took my hands in hers, and said that she’d had a very nice time. I told her that I had too and she smiled, somewhat sadly, I thought, and wished me a good night. (CONTINUED)

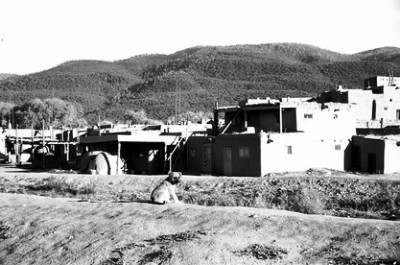

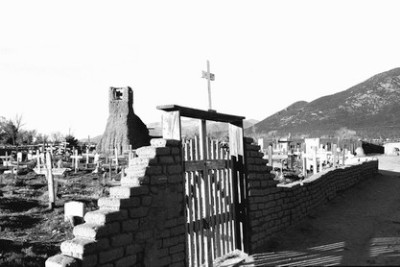

Back in Taos, NM and everything is black and white.

Where you wrote 'wretch' you meant 'retch'.

ReplyDeleteI'm enjoying your story.

Aw, hell. You're absolutely right. Thanks for catching that. Consider it fixed.

ReplyDeleteAnd I'm glad you're enjoying the story. Thanks for your time.

Best Regards,

John