It’s time to head south out of House, New Mexico, drop down off the Llano Estacado, and into the town of Taiban, home of one of the most photogenic churches I’ve ever encountered. From there, we travel Highway 60 west for quite a stretch, past Fort Sumner, Yeso, Vaughn, and Encino. But then, five miles past Encino, we find Negra. So, at the gravel road, let’s turn south and have a look.

Negra, in Torrance County, was established, as were a number of other towns along Highway 60, when the Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Railroad (AT&SF) constructed the Belen Cut-off. This enabled trains to pass through the flat plains and avoid climbing into the northern mountains through Raton Pass. The cut-off came through about 1905 or 1906 and Negra’s post office was established in 1909. However, the post office didn’t last long. It shut down in 1918 with mail to those few still in Negra even then going to Encino

There are a couple stories about how Negra (“black” in Spanish) got its name, including one about a black dog hanging around the early townsite. Robert Julyan suggests the town got its name because of the black soil in the area and mentions the presence of a black water tank. The tank is notable because Negra must’ve had good water and plenty of it. For instance, Encino once got their water from Negra. I was told that a man named Tenorio used a small tanker truck to haul water to town and sell it to the residents. Of course, the steam-powered locomotives would’ve stopped in Negra to get water, as well. After the conversion to diesel engines, Vaughn bought four wells near the tracks from the railroad and, at some point, even Duran, 20 miles away, got water from Negra.

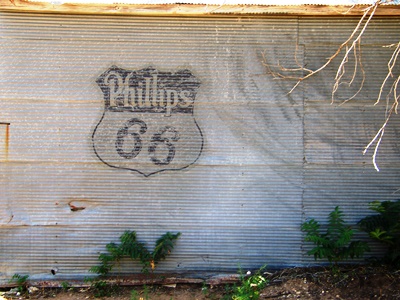

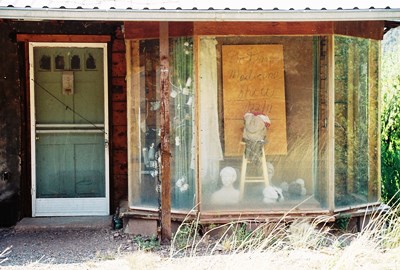

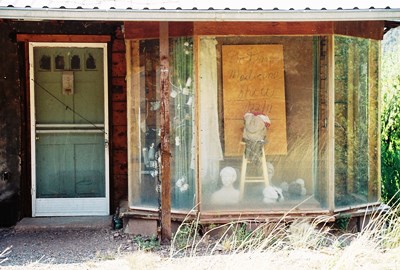

Beyond the above, there’s not much information available on this little town. Nearest the highway is a vacant but nicely intact filling station that might be from as early as the 1920’s. It’s pictured below. (Note “U.S. POST OFFICE” written near the roof. Perhaps this was salvage material.) Behind it is an old tourist court. Both were built by C.E. Davenport, Negra’s first postmaster. A working ranch--the Davenport Ranch--is adjacent to the south. Even farther to the south, across the still-active railroad tracks, there’s a cemetery. To the west, where most of the community once was, only a couple buildings remain. Two, which are not much more than piles of sticks now, were an old school and a teacher’s residence. An adobe structure with a big hole in the middle (shown above) might’ve been a more recent school.

But the gem of Negra is the wonderful rock house, built on the site of an old grocery store, and its attendant barn and outbuildings. Despite the paucity of historical documentation, in a happy twist of fate it’s known who once called this lovely place home. In my post on Encino, I mentioned that there were once four beautiful murals on the walls of the high school gymnasium, which had sadly been torn down. Those murals were done in the very early 1940’s by Hallie Williams, and it is she and her husband Albert (nickname "Ollie") who lived here. Hallie also painted at least one other mural and I’ve been told it still exists, in a store built by Mr. Williams in the 1950’s, also in Encino.

Mr. Williams ran a filling station in Negra—likely the vintage one just mentioned. He also operated a mercantile that fronted the railroad tracks in Encino. This store contained a reportedly very smelly stuffed buffalo head on a wall. Later, in the mid-1940’s, Mr. Williams built a smaller store on the north side of Highway 60. His third store in Encino, then, would be the one containing the mural.

Now, there are some abandoned places that legitimately feel creepy and leaving them brings with it an undeniable sense of relief. Then there are other locations, like the Williams’ homestead, that are peaceful, if not downright soothing. With the sun and clouds playing across the flat land of the eastern plains and a cool breeze rustling the grass, I could’ve stayed there—and, indeed, in all of what remains of Negra—for many more hours than I did. I hope to return soon. I feel like there’s more to be learned out there.

About the only published documentation of Negra that I’ve come across is Dixie Boyle’s "A History of Highway 60 and the Railroad Towns on the Belen, New Mexico Cutoff” It’s a fantastic source for all kinds of info on the towns along the highway. Of course, Robert Julyan’s “The Place Names of New Mexico” handled the naming story, per usual. I even got a few facts, particularly about water, from comments left on the City of Dust Facebook page. Finally, Henry R. sent me a fascinating message about Encino and Negra, as well as background on Mr. Williams, his various stores, and his buffalo. As Henry R. was there back then, his is a fantastic first-person account. His full letter can be read as an update on my post on Encino, which I first published in 2013. Photos of Hallie Williams' now-destroyed murals can be found there, too.

Alright, we won’t have far to go to get to Lucy, the next stop on our never-ending journey.

DECEMBER 2014 UPDATE: As she did by contributing her photos of Hallie William's murals to my post on Encino--the only known shots of those murals, I might add--Dixie Boyle has significantly increased the worth of this post by sending in two great old photos and providing a bit more information on Negra, and the Williams family, in particular:

"Hallie and her sister, Carrie Walker, taught at the Negra School (pictured below) when it was first built, and then in later years Hallie taught music and art classes at her house, which was across the road from the school. The kids would walk across the street to her home for classes. The pile of wood in the middle of the others was the Negra School. During this time the kids made up a wonderful puppet show that Hallie and her students took to other schools. Her daughter, Carrie, still had the puppets when I interviewed her.

"Carrie and Hallie actually moved from Texas to Negra to homestead land together. They built a shack to the south of the school somewhere. Ollie also moved to Negra to homestead. Hallie had a degree from Baylor University and had taught in Texas a few years before arriving in Negra. You can find Hallie and Ollie in the Encino Cemetery.

"In front of the car (above) it's Carrie, Ollie, and Hallie. I just love this picture of them."

Many thanks to Dixie Boyle for yet again providing photos and information that are nearly impossible to find elsewhere. The best place to get this stuff is directly from Dixie's books, in this case, particularly "A History of Highway 60 and the Railroad Towns on the Belen, New Mexico Cutoff", which would almost surely be of interest to anyone reading this post.

The more I learn about the Llano Estacado, or Staked Plain, the massive tableland that covers over 37,000 square miles of west Texas and eastern New Mexico, the more fascinating and evocative I find it. We’ve visited Causey and Pep, both on the western edge of the Llano Estacado, so let’s visit one more Llano town. This one is right beside the Mescalero Escarpment, a long cliff averaging about 200’ high which forms the border on the New Mexico side of the tableland. The Mescalero Escarpment could be (and probably was!) seen as an excellent defense against enemies below. House sits perhaps 15 miles northeast of where this escarpment descends from Taiban Mesa into the wonderful semi-ghost town of Taiban, NM.

Near House is another simply-named town called Field and while the origin of Field’s name is officially obscure, it would seem kind of obvious to anyone passing through. Likewise, you might think that perhaps House was named for a…house. But, in fact, it was named for John L. House and his family, who settled on the current townsite in 1902. John built the first store in 1904 and within two more years House had a post office, with Lucie Jordan House as the first postmistress. I've heard that settlers often arrived by train from Tucumcari and made the surely difficult journey up the escarpment to House on foot where an agent would assign them land to homestead.

(The building above was once a hardware store.)

Below the soil of much of the Llano Estacado is caliche, a hard mineral here known as caprock. In fact, the entire top of the plateau is often referred to as "The Caprock", or even just "The Cap". To make things more confusing, the towering escarpment on the Texas side is the Caprock Escarpment. Anyway, this Caprock Caliche can keep soil depth relatively shallow and, without any features to block wind, the Llano was one of the two regions most devastated by the Dust Bowl, particularly in Texas. Southeastern Colorado-Southwestern Kansas was the other hard-hit region. I wonder how House fared.

There are no descendants of the House family in the area any longer, but the town that bears their name persists. In fact, House is not a ghost town by any stretch. While the population as of the 2000 census was 72, House feels somewhat larger. There are many well-kept homes and gardens and it comes across an active place. So, I apologize to the residents of House for making their home look a little like a true ghost town. I guess it’s just what I do.

(Above is the Sunshine Grocery. Inside were copies of U.S. News & World Report from the early '60's. A quick glance at an issue showed that while the world is very different it's also just about the same.)

While not a ghost town, House has changed considerably over the decades. Its history is difficult to uncover, but someone whose family settled near House in 1906, who began attending House Public School in 1948, told me that the town once had 4 service stations, 3 churches, 3 grocery stores, 3 mechanic shops, 2 hardware stores, 2 feed stores, 1 appliance store, 1 barber shop, 1 blacksmith shop, 1 cafe, 1 school, 1 pool hall, 1 movie theater, a post office, and a potato grading shed. Now, beyond the post office and school, virtually none of it remains.

In 1948, 325 kids attended 1st-12th grade in House and almost every 1/4 section was occupied by a family. But just a handful of years later there were 125 students in the entire school. Much of this decline occurred in the 1950's, when New Mexico suffered a terrible drought and people left the farms around House en masse.

Now, that's about all I could learn about House itself. However, I would be remiss in not mentioning Glen Franklin, born March 18, 1936 in House. Mr. Franklin was world tie-down roping champion in 1965, 1967, and 1968 and was inducted into the ProRodeo Hall of Fame in 1979. It’s said that Mr. Franklin carried a rope while still in diapers and was soon looping every dog, chicken, or human that crossed his path. He rode a horse called Red Light that received its share of credit for Mr. Franklin’s achievements. However, Mr. Franklin didn’t want to travel constantly and retired from rodeoing to ranch near House, which he is still doing to this day.

If I got any geology wrong, I apologize. Please correct me! I used Wikipedia and LlanoEstacado.org as my two primary sources on the Llano and its escarpments. Since there’s not much out there on House, Robert Julyan’s The Place Names of New Mexico tells you more than any other published source just by describing how the town got its name. There’s about as much info on Mr. Glen Franklin at the ProRodeo Hall of Fame site as there is on any other aspect of House! Without the help of Robert W., who has deep roots in House, this post would be much poorer. Michael K. contributed the bit about folks hiking up the escarpment after getting off the train. I thank them both very much!

Next time I believe we’ll head back west down my ol’ friend Highway 60 and visit Negra, New Mexico.

The first thing that strikes one about Pep, at least before visiting, is its name. It might seem a little unusual, except that there’s another town called Pep 60 miles dead east in Texas. In fact, it’s been said that Pep, New Mexico got its name directly from Pep, Texas. It’s also been said that Pep was named for a fortified breakfast cereal popular during the Depression. Neither of those stories is true though and, really, Pep was probably named for the reason you’d guess at first glance.

The place that would become Pep was settled in the fall of 1925 by Edward Cox, who established the first residence and store. T.M. Pearce, who wrote New Mexico Place Names, concluded that Pep got its name because Cox expected it to be a “lively and energetic place.” Apparently Pep was a word used often during the Depression to instill enthusiasm. That’s how Texas got its Pep, too.

I’ve been told that there was a big party to get the town going, including a baseball game and rodeo. The post office opened in 1936--possibly beating Pep, TX to the name--and remains in operation to this day, despite the fact that there are only a handful of residents left. The post office also serves the ranches and farms of the surrounding area, of course, but is now only open in the morning and mail is not delivered every day.

Pep is in Roosevelt County, on the western edge of the legendary rangeland known as the Llano Estacado, or “Staked Plain.” I described the 30,000 sq. mi. Llano Estacado a bit in the last post when we explored nearby Causey. There’s a lot of folklore surrounding why this formidable mesa is known as the Staked Plain. The term is perhaps better translated as “Palisaded Plain,” the “palisaded” likely referring to the high, rocky escarpments that border the tableland, particularly to the east, where one, the Caprock Escarpment, reaches 300 feet tall. A common but probably less accurate explanation is that the “stakes” are really the dried shoots of yuccas, which can rise a few feet above ground and thus appear as scattered stakes as you look out over the landscape. My favorite is that early settlers “staked” their trails with buffalo bones and skulls so that they could follow them back out if they got lost, like macabre bread crumbs. Recently the Hillsboro Historical Society told me that Robert Julyan believes “estacado” may be incorrect and that the original Spanish word could’ve been “estancada” or, “ponded.” Indeed, after a rainfall water collects in the small depressions across the plains and thus “Ponded Plain” might be fitting. Which is right? I’d do like everyone else does and just go with whatever you like best!

where one, the Caprock Escarpment, reaches 300 feet tall. A common but probably less accurate explanation is that the “stakes” are really the dried shoots of yuccas, which can rise a few feet above ground and thus appear as scattered stakes as you look out over the landscape. My favorite is that early settlers “staked” their trails with buffalo bones and skulls so that they could follow them back out if they got lost, like macabre bread crumbs. Recently the Hillsboro Historical Society told me that Robert Julyan believes “estacado” may be incorrect and that the original Spanish word could’ve been “estancada” or, “ponded.” Indeed, after a rainfall water collects in the small depressions across the plains and thus “Ponded Plain” might be fitting. Which is right? I’d do like everyone else does and just go with whatever you like best!

As for personages, science fiction author Jack Williamson was from Pep. Known as the “Dean of Science Fiction,” he published in every decade from the 1920’s to the 2000’s. He also built a little wooden cabin near his parent’s house so that he could write undistracted. I don’t know exactly where it is and I’ve heard it’s decaying…but still standing! I’d sure like to get a photo of it.

So why did Pep not live up to its name? Initially Cox, who owned all the land in town, may have tried to sell it at too high a price during a bad economic time for the country. Maybe it was the name in the first place; Pep, Texas has wound up in a similar state. But the record on Pep is spare, to say the least.

While it’s difficult to uncover the history of the little town, let alone the stories of the people that lived there, that does not make Pep unimportant. In fact, I would argue, quite the opposite. A couple months ago I posted a photo from Pep on the City of Dust Facebook page. After it had been shared around a bit, I found a comment which says more in a few words than I probably have in this whole piece. I don’t know the commenter, but I’d be happy if they somehow stumbled across this post so that I could give them my thanks for such a beautiful sentiment. Hopefully they wouldn’t mind that I’ve used their quote to end this latest installment!

“This post may be the only place in the entire world where the old community of Pep is being discussed. Pause for a moment, if you will, to honor those who gave their all here -- gambling on a new life -- in the Great American Desert.” G. L.

Information for this post came from almost nowhere. Robert Julyan provided the lion’s share in a single paragraph in The Place Names of New Mexico. I cobbled together some of the text on the Llano (or, yar-nah, if you like) from V.H. Whitlock’s book, Cowboy Life on the Llano Estacado. Various other bits were taken from personal correspondence and whatever else I could dig up. I learned a little bit about Pep, TX, the town from where F. Stanley published all those yellow “New Mexico Story” pamphlets, from THIS PAGE. Thanks again to G.L.

Now we’ll go a little bit west and somewhat more north to the also memorably-named town of House.

OCTOBER 2015 UPDATE: As of late September 2015, the entire town of Pep is up for sale. For somewhere around $300,000 you will get 318 acres, a (habitable) residence, a post office, and a community center, as well as everything shown in this post. Interested? Contact Wayne Baker at Master Realty in Portales, NM (575-356-6607). I was tempted to make an offer but my financial planner told me my portfolio is looking a little too thin right now.

MARCH 2016 UPDATE: Well, I finally made it back to Pep to see Jack Williamson's writing shack, which he built with his own hands in the 1930's. There's even a small tub--more of a shallow metal box, really--inside so that he could bathe and continue writing with minimal interruption. I thank the Williamson family for graciously inviting me out to their ranch and also providing a wonderful lunch! I'm very grateful to have been able to photograph this important piece of New Mexico literary history.

We’re about to start a run of posts featuring towns out on the eastern plains of New Mexico, some not far from the Texas state line. A few of these aren’t absolute ghost towns in the sense that the populations range from perhaps a couple individuals to around 70. But they’re all pretty obscure. So obscure, in fact, that in many cases all I can find on them, historically-speaking, is what Robert Julyan has to say in The Place Names of New Mexico. But, to me, these are fascinating, picturesque, and photogenic places, each persisting as best it can, whether populated or not, on the lonesome, windswept prairie.

Let’s start with Causey, New Mexico, located in Roosevelt County at the crossroads of NM 114 and 321, 35 miles southeast of Portales and about a mile from Texas. Despite some previous conjecture that the moniker was intended to flatter a railroad VP and get a line through Causey, it now seems agreed that the town was named for at least two of the Causey brothers, T.L. “George” and John. The brothers were buffalo hunters, working in the southeastern part of the state and George, in particular, established a reputation for being one of the most successful in the history of the American West. Estimates by outside observers put the number of buffalo he personally killed at around 40,000. One of George’s hunting companions, George Jefferson, known as “Old Jeff,” said “Causey killed more buffaloes in one winter…than Buffalo Bill Cody killed in his entire lifetime.”

The problem with shooting that many buffalo is that eventually you run out. Of course, that’s how it went and, after hunting through the 1870’s, by 1882 Causey had shot the last of the wild buffalo on what is known as the Llano Estacado, or “Staked Plain,” of eastern New Mexico.

While George Causey generally operated to the south, the town of Causey is on the west central part of the Llano Estacado, one of the largest tablelands in North America, the majority of which is in northwest Texas. Coronado had this to say upon stumbling onto the Llano in 1541:

"I reached some plains so vast, that I did not find their limit anywhere I went, although I traveled over them for more than 300 leagues...with no more land marks than if we had been swallowed up by the sea...there was not a stone, nor bit of rising ground, nor a tree, nor a shrub, nor anything to go by."

To translate for those of us no longer using leagues, Coronado covered more than 1000 miles.

Thus turning to ranching on the Llano, George Causey established himself south of Lovington, maybe 60 miles from present-day Causey. Mr. Causey promoted the suitability of eastern New Mexico for ranching and farming and, as one of the earliest settlers in the area, opened it up for those who followed, not least by being the first to discover the rich supply of groundwater in the region.

In 1902, Causey was thrown from a horse during a mustang round-up, badly injuring his spine. After traveling all over the country depleting his finances in a failed effort to find medical relief for his severe headaches, and increasingly disenchanted with the rapidly changing West, Causey sold his ranch to pay off debt, married his nurse, and moved near Kenna, 30 miles southwest of the town that bears his family name. He shot himself in his bed on May 19, 1903, his body discovered by his nephews, Vivian and Ralph, who’d heard the report of their uncle's gun. I don’t know if the town of Causey had been established by that time or not; the post office didn't open until 1907.

The earliest date I can put on Causey is 1907, when the post office opened. It remains operational to this day. The townsite was actually moved by Ezra Ball sometime after WWI and is now three miles north of where it was first established. These days you will find some well-kept homes and a few residents. The population as of the 2000 census was 52 and I imagine that’s decreased a little. There is also the ruin of a massive WPA-built school which is collapsing and disappearing into the overgrowth. It was surprising to me that such a large school existed in Causey, but F. Stanley reported in “The Causey (New Mexico) Story,” published in 1966, that there were at least 150 students attending the school in 1942. That's more than I would've guessed. Here’s a taste of how things were back then:

"The Causey school has over fifty in high school and over one hundred in grade school, Supt. L. E. O'Hare stated last weekend. The attendance has been good. The school board has not decided when it will dismiss school for crop gathering, but Supt. O'Hare is of the opinion it will be about the first of next month. There have been no resignations of teachers so far." (Sept. 7, 1942) The school is pictured below.

Also, in 1960, the senior class was said to have visited the "Insane Asylum" in Las Vegas, NM as part of a long field trip. I wonder if the kids lobbied to put that on the itinerary.

Stanley himself said of Causey that, “The most surprising thing is the school system and the fire house, worthy of larger cities.” He went on: “Time is unimportant to the teachers. They give so much of it to the school. Many a trip took me through Causey and teachers would be noted at their desks far into the night. There may be a thousand reasons for this; there may be none save that they love their work.”

Next to the school is a massive metal, armory-like structure with a caved-in roof. I've heard this was the school gymnasium and also held the agricultural shops. Someone else told me they’d played basketball inside the school, which would indicate the gym was there. Heck, maybe there were gyms in both places. (UPDATE: There were two gyms! I've been told the bigger was the "New Gym," probably built in the mid-to-late 1960's. However, it may not have been used as such for long because the school closed sometime in 1970-1971.) Inside the armory were a couple bedraggled pick-up trucks and the first abandoned semi tractor I’ve ever seen, now crushed under the huge roof.

F. Stanley noted in 1966 that, “Causey had a long, hard road to travel, but it has made the grade and the future looks good.” It is referred to as “one of the business centers of Roosevelt County,” with a population of 234 as early as 1920. Like so many small towns, the future Stanley spoke of appears to have, in the end, been at least as hard as the past.

Information for this post came from the aforementioned The Place Names of New Mexico, as well as F. Stanley’s long out of print “The Causey (New Mexico) Story.” Some biographical information on George Causey can be found at the Texas State Historical Society. Wikipedia will give you demographics. If you get really into George Causey and the Llano, you will want to read Cowboy Life on the Llano Estacado, written by his nephew, V. H. Whitlock aka Ol’ Waddy. Roosevelt County History and Heritage, by Jean M. Burroughs, wife of former NM governor John Burroughs, documents the county, but doesn’t say a whole lot about Causey.

Next time…Pep, NM!

It’s been awhile since we’ve visited an operating historic hotel, but over the last couple years we've seen the Express St. James in Cimarron and the Schaffer Hotel in Mountainair. So, it's fitting that we also take a look at the recently restored Murray Hotel in downtown Silver City, NM. A beautiful Art Deco building, it was constructed on the site of the Broadway Hotel, which was torn down in 1925. Across the street is the Palace Hotel, another lovely place, which opened March 1, 1900 in the former Meredith and Ailman Bank building, built 1882.

It’s been awhile since we’ve visited an operating historic hotel, but over the last couple years we've seen the Express St. James in Cimarron and the Schaffer Hotel in Mountainair. So, it's fitting that we also take a look at the recently restored Murray Hotel in downtown Silver City, NM. A beautiful Art Deco building, it was constructed on the site of the Broadway Hotel, which was torn down in 1925. Across the street is the Palace Hotel, another lovely place, which opened March 1, 1900 in the former Meredith and Ailman Bank building, built 1882.

Construction on the Murray Hotel began in 1937 and, with the country still reeling from the Great Depression, it was no trouble to get very skilled craftsmen to build the joint, which was originally designed to have 52 rooms, three retail stores, a restaurant, a coffee shop, a bar, and a luxurious lobby. Steam closets and low shower heads were even installed in the bathrooms so that women would be able to get the wrinkles out of their clothes while cleaning up after a long, hot, bumpy, and rumple-inducing journey.

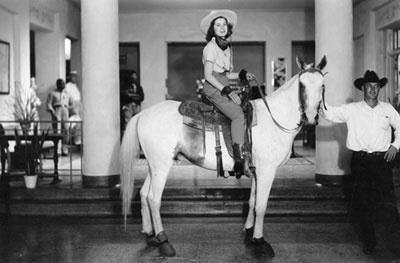

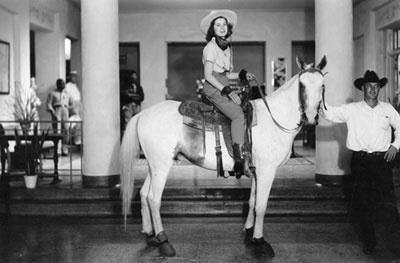

Below is an iconic photo of 16-year-old Martha Ryan, granddaughter of the hotel’s developer and NM state senator W.D. Murray, on her horse in the terrazzo-floored lobby. It was taken to promote a Fourth of July Rodeo in 1938, before the hotel was even finished. Incidentally, W.D.’s grandson, Murray Ryan, was a long-time NM state representative. The Murray officially opened in October ’38 with a grand celebration. Anyone who was anyone in southern New Mexico turned out, including hotel magnate and Paris Hilton antecedent Conrad Hilton.

In 1949, as the American economy boomed post-WWII, another 48 rooms were added to the Murray in a north tower, making an even 100, and a spring-suspended maple-floored ballroom was installed. The parties held in the ballroom remain legendary among local old-timers. The hotel also took on a more explicitly Western vibe and the bar, which had gone by the mining-themed moniker Copper Lounge, became the Branding Room, where ranchers and businessman wheeled and dealed beside a large mural depicting local ranch brands.

For decades the Murray was perhaps the social center in Grant County. However, by the late 1970’s a lot had changed and the hotel was struggling to stay afloat. Area mines had closed, travelers were staying elsewhere and, by the early 1990’s, the once-grand hotel was shuttered and appeared abandoned. Eventually, local residents decided that the iconic building should be saved, but it would change hands several times in the ensuing years before anyone could figure out quite what to do with it.

Finally, in 2005, the Murray was bought by the Albershardt’s, who began a long and expensive restoration. Extensive cleaning was required as the hotel had seen its share of vandals and homeless residents and it was a given that the original Art Deco design elements needed to remain intact. The hotel re-opened for business in spring 2012 and, at this point, I believe as many as 82 rooms have been restored, as well as the ballroom and various banquet and meeting rooms.

My visit to the Murray Hotel occurred last Christmas during a freak (well, this is southern New Mexico) blizzard that earlier had me cut-off from my desired route to Silver City through Hillsboro,  Kingston, and the Black Range. The Murray, however, was warm and inviting and sipping complimentary herbal tea in the lobby, which looks just as it did when Martha Ryan parked her horse there, was…well, not exactly a rugged, Western way to spend a holiday evening. But I can’t ever complain when in Silver City, even if snowbound and unable to brave the elements for just the short walk to Billy the Kid’s childhood cabin. The rooms were likewise cozy and still have a vintage feel to them, despite the extensive updates.

Kingston, and the Black Range. The Murray, however, was warm and inviting and sipping complimentary herbal tea in the lobby, which looks just as it did when Martha Ryan parked her horse there, was…well, not exactly a rugged, Western way to spend a holiday evening. But I can’t ever complain when in Silver City, even if snowbound and unable to brave the elements for just the short walk to Billy the Kid’s childhood cabin. The rooms were likewise cozy and still have a vintage feel to them, despite the extensive updates.

Obviously, I highly recommend a stay at the Murray Hotel, which has been so faithfully restored as to leave one pretty convinced they’ve entered an Art Deco time portal back to the late 1930’s. Now if they would just re-open the Branding Room and maybe book a Duke Ellington gig.

Information for this post came mostly from the Murray Hotel itself. Check out their website and Facebook page for reservations, correspondence, and all that kind of thing. A tour of the hotel can be found on You Tube.

Alright, enough of the shiny and new(-looking). Next time it’ll be back to some abandonment. We’ll travel way across the state and return to the eastern plains near the Texas border to hit some little-known towns that I can barely dig up any information on. So, those of you who have been fervently wishing for less time-consuming posts will be sighing with relief. I’ll be sighing with relief myself, actually.

Like Hillsboro, Kingston, New Mexico isn’t a ghost town. But it’s also not the place of which it was said that on nights when the miners had been paid you couldn’t walk ninety feet in 30 minutes for the crowd, a place with 22 saloons, 14 grocery stores, three hotels, three concurrently-operating newspapers, an opera house, and a school, a place where the bank once held $7,000,000 in silver and the population topped 7,000. Nope, it’s not that place now. And it never was. There may be few Old West mining boom towns that have had their history so exagerrated. Kingston has even been considered to have once been the biggest town in territorial New Mexico.

Now, everyone agrees that in the early 1880’s precious metal, particularly silver, was found in the area. Ralph Looney’s Haunted Highways recounts the story that Kingston’s establishment can be traced to a drunkard, Jack Sheddon, who became such a nuisance in Lake Valley that the sheriff put him on a burro with food and whiskey and sent him north. En route to Chloride, he made a stop near what would become Kingston, had a good long drink, and passed out on a rock. When he came to, he noticed that his stony pillow had flecks of metal in it. This was bornite, a silver ore, and he quickly established the Solitaire Mine. Soon prospectors were descending from every direction. It’s a great tale, but not really true. Prospecting was underway before Sheddon even arrived (he at least did exist) as a few miners had already moved the 10 or so miles west from Hillsboro, which had been established in 1877.

(The above photo shows a house that was also once a store on Kingston's eastern edge. The sign in the window says, "Dr Dans Medicine Show 1/22/11". Near the bottom of this post is a shot of the microwave tree around the side. Interesting, eh?)

In the fall of 1882, James Porter Parker, General G.A. Custer’s former roommate at West Point, platted Kingston, which took its name from a local mine, the Iron King. Soon it was reported by the Tombstone Epitaph in Arizona that there were 45 men working area mines. By 1885, a year after Kingston’s oft-reported peak population of 7,000, Territorial Census figures show 329 residents in Kingston and the adjacent Danville Camp combined, even with Spanish and Chinese included in the tally.

It may well have been a rowdy place though. In an 1886 edition of the St. John’s Herald out of east-central Arizona (at the time Kingston didn’t have one newspaper) a citizen expressed upset at their town’s lack of a school, church, or, indeed, any public institution. Reverend S.W. Thornton even referred to Kingston as “the typical mining town in all its wickedness.” In 1888, construction of a stone church began which would serve Kingston’s now-1,000 residents. Sometimes claimed to have been spontaneously financed by prostitutes, gamblers, and dancehall girls, it’s more likely that Rev. N.W. Chase solicited the funds.

In 1890, according to the U.S. Census Bureau, Kingston’s population reached 1,449, a count it probably never surpassed by much. The 1893 economic panic sent silver prices crashing and the number of Kingston’s occupants plummeting quickly back into the low hundreds at best. By the time it was really all over in the early 1900’s almost $7,000,000 in precious metal had been mined in the vicinity, not an inconsiderable sum. But it took over 20 years; that amount was never in the Percha Bank at one time.

Even the usually no-nonsense Philip Varney slips up when it comes to Kingston, mentioning in New Mexico’s Best Ghost Towns that Chief Victorio’s band of Apaches once descended on the town, but because the miners were assembling a hunting party and thus had their firearms at hand they were able to quickly drive the attackers out. It’s said Victorio decided to leave Kingston alone after that and the happy populace named their new three-story hotel The Victorio in his honor. The problem is that Victorio died in 1880, two years before Kingston was established. It’s not entirely Varney’s fault; there are many stories about Victorio and his band’s depredations in and around Kingston. And Varney didn’t have Wikipedia in the 1970’s.

but because the miners were assembling a hunting party and thus had their firearms at hand they were able to quickly drive the attackers out. It’s said Victorio decided to leave Kingston alone after that and the happy populace named their new three-story hotel The Victorio in his honor. The problem is that Victorio died in 1880, two years before Kingston was established. It’s not entirely Varney’s fault; there are many stories about Victorio and his band’s depredations in and around Kingston. And Varney didn’t have Wikipedia in the 1970’s.

You may also hear of the ironically-named Virtue St., on which was an infamous Kingston brothel. While you will find a very short side street named Virtue today, it was created after Kingston's initial abandonment. But don't fret! The world has not gone entirely topsy-turvy; there certainly was a brothel in early Kingston.

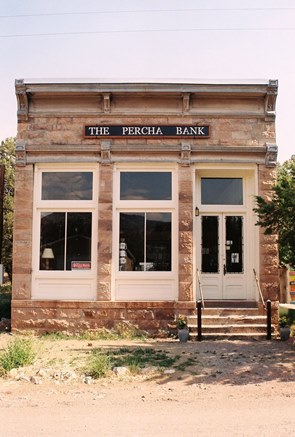

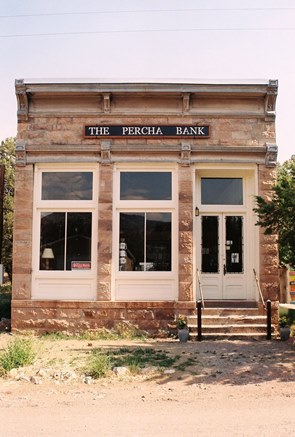

Walking the two short thoroughfares, many have wondered how a town could’ve risen and fallen so precipitously. Since it didn’t, it’s not as surprising that only one historic building exists wholly intact: the Percha Bank. The old Assay Office, remodeled as a private home, and a vastly reconfigured hotel—The Victorio—also persist. Floods and fires have certainly done their damage, but there was never as much to disappear as is usually imagined.

Much of the confusion over Kingston is attributable to James A. McKenna’s classic Black Range Tales, which, it should be noted, contains the word tales in the title and not facts. Some of McKenna’s yarns, which most ghost town sources at least reference, take place in a Kingston of 7,000 rabble rousers, "the metropolis of the Southwest" which, while possibly true to the spirit of the day, never quite existed. The same year that Black Range Tales was published, 1936, Madame Sadie Orchard told an interviewer of a peak population of 5,000. Few having actually been there, such wild overestimates made their way into subsequent Kingston literature. In the end, maybe the Kingston of myth is just one of those places in the Wild West of our collective imagination that people wanted to exist so badly that it was finally wished into being. It’s not the worst thing to have happened to history, I suppose.

"the metropolis of the Southwest" which, while possibly true to the spirit of the day, never quite existed. The same year that Black Range Tales was published, 1936, Madame Sadie Orchard told an interviewer of a peak population of 5,000. Few having actually been there, such wild overestimates made their way into subsequent Kingston literature. In the end, maybe the Kingston of myth is just one of those places in the Wild West of our collective imagination that people wanted to exist so badly that it was finally wished into being. It’s not the worst thing to have happened to history, I suppose.

Craig Springer, Black Range historian, founding member of the Hillboro Historical Society, and co-author of Around Hillsboro, does the best (and, to date, just about only) full-blown analysis of Kingston’s popular history, "Kingston Myth," in the June 2012 issue of Desert Exposure, turning up many inaccuracies and doing an excellent job of tracking down primary sources of more reliability. I reference his work throughout this post and thank him for his input.

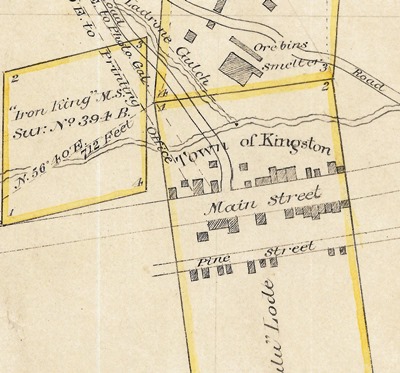

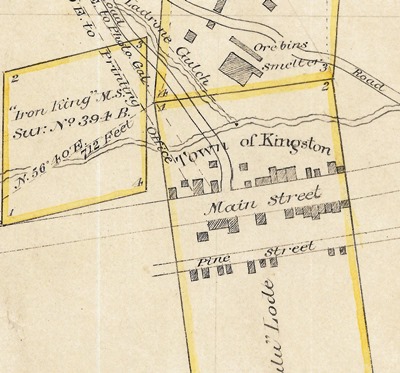

Below is the layout of Kingston circa 1887, which shows that three years after the town's supposed peak the place was still not real big. The plat is from the General Land Office of the BLM, which has all kinds of good stuff.

Most accounts of Kingston mention Victorio’s harassment, but a quick check of Wikipedia will confirm that he died on October 14, 1880. You might also have heard that Billy the Kid visited Kingston, but as he was shot by Sheriff Pat Garrett on July 14, 1881 in Fort Sumner it would’ve had to have been a very different sort of ghost town then indeed. Finally, if you’re in Kingston don’t forget to check out the real and factual Percha Bank, now a museum! Call before you visit as hours are limited.

Next post, I believe we’ll have a look at the newly remodeled Murray Hotel in Silver City. Then there will be a flurry of posts about towns on the eastern plains of New Mexico that not much has been written about. With such enforced brevity I might even be able to post more often!

Hillsboro, New Mexico, at the foot of the Black Range, almost 20 miles west of I-25 on NM 152, the scenic route to Silver City, is not a ghost town, as anyone that lives there will tell you. But it’s also not quite the place it was in the early 1890’s, when 2000 people called it home. Perhaps one-third of these were children, indicating something like the presence of family values, a bit unusual in a Wild West mining town of the time. (As of the 2010 census, Hillsboro’s population was 124.) Also, Hillsboro has plenty of historic heft, which makes it rather nice for inclusion here at City of Dust.

Hillsboro was a mining town and a gold mining town at that. In April 1877, Dan Dugan and Dave Stitzel found color along Percha Creek, just beside present-day Hillsboro, and suddenly a rush was on. Four months after Dugan and Stitzel had their ore assayed at $160 in gold to the ton someone built a house nearby and by December, with fresh claims springing up all around, it was decided to name the newborn town.

Over the years, I’ve put a lot of effort into describing the origins of the monikers of some of these places, but Hillsboro is easy: Everyone says they pulled the name out of a hat. Originally, it was Hillsborough, but all those extra letters were quickly deemed unnecessary. Or is it so easy? A lesser-known version has it that Joseph Trimbel Yankie, possibly the third prospector to arrive in the area, was given the honor of choosing the name. Because he was from Hillsboro, Ohio, he chose...Hillsboro. This account is now considered correct. Remember, when in doubt, always pick the less-interesting story.

(I *think* the above building, on Percha Creek, was the Romelia Chavez Luna home, built sometime before 1893.)

Within two years, Hillsboro had a population of 300, as well as saloons, grocery stores, and a post office. It also had a problem with Apache raids, so four companies of soldiers were stationed nearby to provide protection. Once, when Victorio went raiding, everyone moved across the mountains to the mining camp of Georgetown to wait things out.

A lot of money was soon being pulled out of the region and Hillbsoro became a center of activity, as well as the Sierra County seat in 1884, eventually resulting in the construction of an ornate, two-story brick courthouse for $17,000 in 1892. The sturdy, red-brick Union Church was also built that year. In the end, six million dollars in gold and silver was found in the rugged landscape, with all the attendant trading, banking, ranching, and rabblerousing such a thing would engender. Stagecoaches ran back and forth between adjacent Black Range towns and, of course, they were often robbed, so the jail was plenty big.

as well as the Sierra County seat in 1884, eventually resulting in the construction of an ornate, two-story brick courthouse for $17,000 in 1892. The sturdy, red-brick Union Church was also built that year. In the end, six million dollars in gold and silver was found in the rugged landscape, with all the attendant trading, banking, ranching, and rabblerousing such a thing would engender. Stagecoaches ran back and forth between adjacent Black Range towns and, of course, they were often robbed, so the jail was plenty big.

Hillsboro’s last jail, a stone affair built near the courthouse in the mid-1890’s, housed some interesting people, including Oliver Lee, James Gilliland, and William McNew, accused in the infamous 1896 disappearance near White Sands of Judge Albert J. Fountain and his eight-year-old son Henry. Fountain had been indicting suspected cattle thieves in Lincoln and Lee, Gilliland, and McNew had each been named. Incidentally, despite having been an outspoken opponent of Billy the Kid and his gang, Fountain had been selected to defend Billy in his 1881 trial for the murder of Sheriff William Brady, a case he obviously lost.

In 1899, after Lee and Gilliland had escaped Sheriff Pat Garrett and following political wrangling too labyrinthine to go into here, the accused were brought to Hillsboro, trial proceedings being moved from Las Cruces at the request of the defense. Oliver Lee and Jim Gilliland were tried for the murder of Henry but not his father and, after the judge pulled jurors out of their beds at 11:30 PM demanding a decision, a verdict of “not guilty” was delivered in eight minutes. Despite blood and signs of struggle at the scene of the alleged crime, there were still no bodies to prove that anyone was actually dead. Charges against McNew were dismissed. The case has never been solved.

Valentina Madrid, a sixteen-year-old girl, and her seventeen-year-old friend, Alma Lyons, also knew the jail. In 1907, they were accused of poisoning Valentina's husband by sprinkling his coffee with "Rough on Rats" for a week. The girls said they were forced to do it by Valetina's would-be suitor, Francisco Baca, though he was acquitted. The girls were sentenced to be hung, but public outcry got them life sentences. Thirteen years later, both girls were pardoned by Governor Octaviano Larrazolo on the condition they secure “honorable employment," remain in New Mexico, and never set foot in Sierra County again.

Hillsboro had already begun a steep decline by the late-1890’s, but revived a bit during WWI, then started to decline again in the 1930’s, although after a devastating flood in June 1914 the town was never going to be the same. In 1938, Hillsboro lost the county seat to Hot Springs (now Truth or Consequences). The story goes that residents of Hillsboro kept traveling to Hot Springs to bring all the county’s files and documents back to Hillsboro. This allegedly happened so often that the courthouse was eventually taken apart brick-by-brick so there would no longer be anywhere to bring the files back to. Whether that’s true or if the courthouse in Hillsboro was simply sold in 1939 for $440 to provide construction material for the new one in Hot Springs, I can’t say. The courthouse may have even remained whole into the mid-1940's. But it was never entirely dismantled and what remains is a picturesque ruin.

In 1938, Hillsboro lost the county seat to Hot Springs (now Truth or Consequences). The story goes that residents of Hillsboro kept traveling to Hot Springs to bring all the county’s files and documents back to Hillsboro. This allegedly happened so often that the courthouse was eventually taken apart brick-by-brick so there would no longer be anywhere to bring the files back to. Whether that’s true or if the courthouse in Hillsboro was simply sold in 1939 for $440 to provide construction material for the new one in Hot Springs, I can’t say. The courthouse may have even remained whole into the mid-1940's. But it was never entirely dismantled and what remains is a picturesque ruin.

Evidence of Hillsboro’s past is all around, including in the Black Range Museum, once the Ocean Grove Hotel. The hotel also functioned as a high-end brothel established in 1886 by Sarah Jane Creech, better known as Sadie and usually (and mistakenly) said to be British, when she was just 21 years old. Amongst other things, Sadie and her girls were known for fearlessly tending to the town's residents during the influenza pandemic of 1918.

Hillsboro’s present is as a charming small town nestled in the Black Range with a couple cafes and restaurants and The Enchanted Villa Bed & Breakfast. While there might not be much gold in them thar hills anymore, there’s still plenty of reason to stay in Hillsboro.

I attempted to rectify information from three sources for this post, Haunted Highways, published in 1968 by Ralph Looney, New Mexico’s Best Ghost Towns, published in 1981 by Philip Varney, and Ghost Towns Alive, published in 2003 by Linda Harris. I did my best to sort out the minor discrepancies and omissions amongst them, but you know how that goes. All state that Hillsboro's name was picked from a hat. The Place Names of NM is one of the few published sources that mentions both naming stories, but locals (and the Albuquerque Evening Citizen) know it was Yankie. The story about Valentina Madrid and Alma Lyons came from the Hillsboro Historical Society, who also commemorated the presumed murder of Albert and Henry Fountain.

Now we’ll head west a few miles to Hillsboro’s misunderstood younger sister, Kingston.

There’s not been much written about Engle, New Mexico over the years. The usual ghost town books I consult only mention the town in the context of its stage and rail connections to other places. But Engle, now not much more than a handful of buildings persisting in the relentless heat of a dusty former rail stop 20 miles east of Truth or Consequences, sits within an area that has played a major role in the histories of Spain, Mexico, and the U.S. Currently, it is the home base for an enterprise owned by a well-known cable television magnate and, in the future, may be passed through by some very wealthy people on their way to…orbit.

It makes sense to start the story of Engle with the Jornada del Muerto, the “Journey of Death,” which runs through the town. Or, perhaps, a couple hundred feet west, if you want to get technical. Considered the most treacherous part of El Camino Real, this stretch, beginning slightly north of Las Cruces, traversed a desolate wasteland devoid of water, firewood, or shelter. So, if the Apache didn’t get you, the desert itself might. Just imagine traveling over an ancient lava bed by horse in the early 1600’s without a Wal-Mart or 7-11 in sight. It might sound like heaven now, but let’s not romanticize too much. The closest city to the north, a long 90 miles away, was named Socorro (i.e., succor, relief, aid, etc.) for a reason. But, all that aside, plenty of travelers did survive the journey and thus, for many years, one of the most important trade routes in the history of the world passed right outside what would become Engle’s front door.

Founded in 1879, Engle was, like so many other towns in the West, born of the railroad. Named for R.L. Engle, the railroad engineer who supervised construction of the line through town, due to a paperwork error Engle was officially known as "Angle" for its first six months. An attempt to rename the town "Engel" in the 1920's, in honor of Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe (AT&SF) vice-president Edward J. Engel, was halted in the 11th hour when "cowboy chronicler" Eugene Manlove Rhodes asked Senator Bronson Cutting to pull some strings.

The railroad soon built a station and Engle thrived as a shipping point for cattle from surrounding ranches. Horses, mules, stagecoaches, and eventually trains transported ore east from the more remote mining towns on the edge of the Black Range, including Cuchillo, Chloride, and Winston (then known as Fairview), and from Engle it all moved on to larger cities, such as El Paso. A post office opened in 1881 and the place was off and running.

From 1911-1916, the construction of Elephant Butte Dam, about 10 miles west, increased the population greatly. Housing in Engle was convenient and the town was the switching point for the AT&SF spur that carried materials to the dam. The peak at that time was about 500 residents, but with completion of the dam workers left immediately and Engle began its decline. By 1919, 300 people, over half the peak population, had left. Seven years later, only 75 souls remained. In 1945, much of the land to the east and south of town was claimed by the federal government for White Sands Missile Range, snuffing out most of Engle’s remaining light. But not quite all of it.

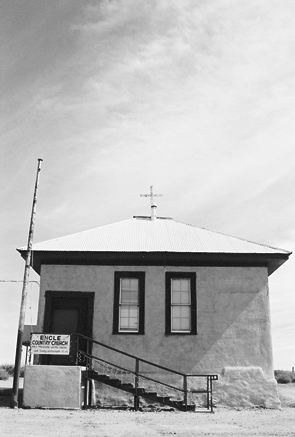

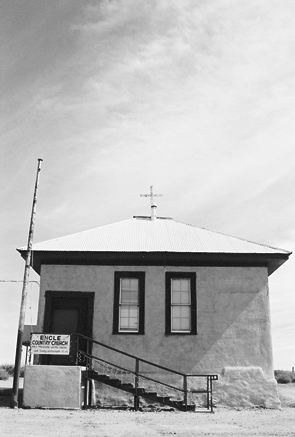

While the post office closed in 1955, a few people live in Engle yet. The train still rumbles by, however, it doesn’t stop. Not many original buildings stand, but one, the old schoolhouse, occupies what would seem to be the spiritual center of town. That’s not just on account of it being the most prominent building you see as you cross the railroad tracks, but because it’s now the Engle Country Church featuring “bible preaching and gospel singing” at 10 AM on the third Sunday of every month. Conveniently, there are some vineyards being tended nearby, too, in case the supply of wine runs low.

Not many original buildings stand, but one, the old schoolhouse, occupies what would seem to be the spiritual center of town. That’s not just on account of it being the most prominent building you see as you cross the railroad tracks, but because it’s now the Engle Country Church featuring “bible preaching and gospel singing” at 10 AM on the third Sunday of every month. Conveniently, there are some vineyards being tended nearby, too, in case the supply of wine runs low.

Engle has also become the headquarters of the Armendaris Ranch, a massive 362,885-acre spread owned by Ted Turner of CNN and Jane Fonda fame. Word is that when he comes to town, his entourage lays the necessary groundwork a few days in advance and then Ted blows in, checks on his buffalo, maybe does a little hunting, and is off again. Turner owns two other huge ranches in New Mexico and is the second-largest private landowner in the state.

Moving into the totally surreal, Engle is poised to be a way station for those heading to Spaceport America. Anyone not flying directly into and out of the spaceport or coming up from Las Cruces would be obliged to go through Engle. It is strange to imagine that some of the richest, most famous people on the planet might see Engle shortly before they are launched into orbit for a few seconds. On the other hand, those who traveled the Jornada del Muerto hundreds of years ago might well appreciate the irony. For the dusty little patch of Chihuahuan Desert on which Engle persists has a habit of being a quiet witness to great journeys.

It’s not easy finding information on Engle. The usual physical sources overlook it, but on-line you can find most of what seems to exist at ghosttowns.com. Even Legends of America won’t tell you anything about the town. But they will tell you that, in the 1880’s, Bill Hardin, famous gunfighter John Wesley Hardin’s first cousin, was lynched by a mob after killing a man near Engle. Oddly, the “Ghost Towns of Sierra County New Mexico” promotional card is one of the better resources, even at all of five sentences. NM Place Names recounts how Engle came to be called Engle (and then almost wasn't). Otherwise, Wikipedia will tell you about the Jornada del Muerto and Spaceport America will tell you about Spaceport America.

Next time we’ll cross I-25 and move nearer the Black Range to visit the relatively well-known partial ghost town of Hillsboro, NM. Until then, have a happy 4th of July and safe travels, everyone.

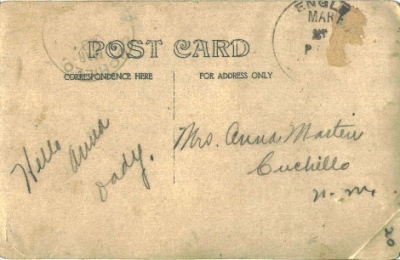

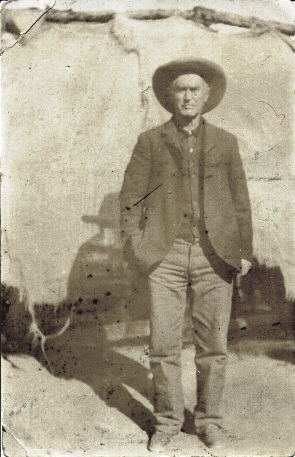

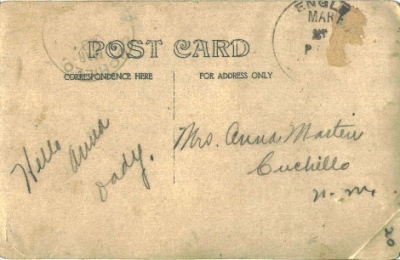

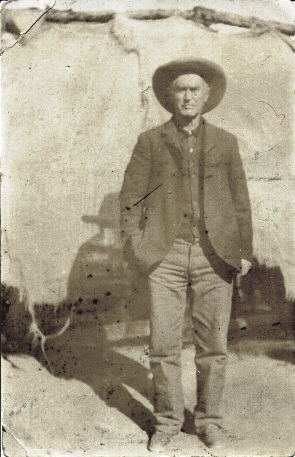

JULY 2014 UPDATE: Mr. William M., former resident and continued aficionado of the wide-open spaces of New Mexico, has contributed a very interesting photo postcard. Postmarked from Engle to Mrs. Anna Martin of Cuchillo, NM, William guesses the card is from about 1910. Note the sparse address and even sparser message, which reads, "Hello Anna Dady (sic)." The few words speak volumes about this time and place. We can only assume that the stoic desert fellow pictured is indeed Anna's father, probably captured by a photographer traveling through Engle. William adds, "It was sent from one ghost town to another ghost town – only in New Mexico."

has contributed a very interesting photo postcard. Postmarked from Engle to Mrs. Anna Martin of Cuchillo, NM, William guesses the card is from about 1910. Note the sparse address and even sparser message, which reads, "Hello Anna Dady (sic)." The few words speak volumes about this time and place. We can only assume that the stoic desert fellow pictured is indeed Anna's father, probably captured by a photographer traveling through Engle. William adds, "It was sent from one ghost town to another ghost town – only in New Mexico."

Thanks for the great addition, William!

where one, the

where one, the

It’s been awhile since we’ve visited an operating historic hotel, but over the last couple years we've seen the

It’s been awhile since we’ve visited an operating historic hotel, but over the last couple years we've seen the

Kingston, and the Black Range. The Murray, however, was warm and inviting and sipping complimentary herbal tea in the lobby, which looks just as it did when Martha Ryan parked her horse there, was…well, not exactly a rugged, Western way to spend a holiday evening. But I can’t ever complain when in Silver City, even if snowbound and unable to brave the elements for just the short walk to Billy the Kid’s childhood cabin. The rooms were likewise cozy and still have a vintage feel to them, despite the extensive updates.

Kingston, and the Black Range. The Murray, however, was warm and inviting and sipping complimentary herbal tea in the lobby, which looks just as it did when Martha Ryan parked her horse there, was…well, not exactly a rugged, Western way to spend a holiday evening. But I can’t ever complain when in Silver City, even if snowbound and unable to brave the elements for just the short walk to Billy the Kid’s childhood cabin. The rooms were likewise cozy and still have a vintage feel to them, despite the extensive updates.

but because the miners were assembling a hunting party and thus had their firearms at hand they were able to quickly drive the attackers out. It’s said Victorio decided to leave Kingston alone after that and the happy populace named their new three-story hotel The Victorio in his honor. The problem is that Victorio died in 1880, two years before Kingston was established. It’s not entirely Varney’s fault; there are many stories about Victorio and his band’s depredations in and around Kingston. And Varney didn’t have

but because the miners were assembling a hunting party and thus had their firearms at hand they were able to quickly drive the attackers out. It’s said Victorio decided to leave Kingston alone after that and the happy populace named their new three-story hotel The Victorio in his honor. The problem is that Victorio died in 1880, two years before Kingston was established. It’s not entirely Varney’s fault; there are many stories about Victorio and his band’s depredations in and around Kingston. And Varney didn’t have  "the metropolis of the Southwest" which, while possibly true to the spirit of the day, never quite existed. The same year that Black Range Tales was published, 1936,

"the metropolis of the Southwest" which, while possibly true to the spirit of the day, never quite existed. The same year that Black Range Tales was published, 1936,

as well as the Sierra County seat in 1884, eventually resulting in the construction of an ornate, two-story brick courthouse for $17,000 in 1892. The sturdy, red-brick Union Church was also built that year. In the end, six million dollars in gold and silver was found in the rugged landscape, with all the attendant trading, banking, ranching, and rabblerousing such a thing would engender. Stagecoaches ran back and forth between adjacent Black Range towns and, of course, they were often robbed, so the jail was plenty big.

as well as the Sierra County seat in 1884, eventually resulting in the construction of an ornate, two-story brick courthouse for $17,000 in 1892. The sturdy, red-brick Union Church was also built that year. In the end, six million dollars in gold and silver was found in the rugged landscape, with all the attendant trading, banking, ranching, and rabblerousing such a thing would engender. Stagecoaches ran back and forth between adjacent Black Range towns and, of course, they were often robbed, so the jail was plenty big.

In 1938, Hillsboro lost the county seat to Hot Springs (now Truth or Consequences). The story goes that residents of Hillsboro kept traveling to Hot Springs to bring all the county’s files and documents back to Hillsboro. This allegedly happened so often that the courthouse was eventually taken apart brick-by-brick so there would no longer be anywhere to bring the files back to. Whether that’s true or if the courthouse in Hillsboro was simply sold in 1939 for $440 to provide construction material for the new one in Hot Springs, I can’t say. The courthouse may have even remained whole into

In 1938, Hillsboro lost the county seat to Hot Springs (now Truth or Consequences). The story goes that residents of Hillsboro kept traveling to Hot Springs to bring all the county’s files and documents back to Hillsboro. This allegedly happened so often that the courthouse was eventually taken apart brick-by-brick so there would no longer be anywhere to bring the files back to. Whether that’s true or if the courthouse in Hillsboro was simply sold in 1939 for $440 to provide construction material for the new one in Hot Springs, I can’t say. The courthouse may have even remained whole into

Not many original buildings stand, but one, the old schoolhouse, occupies what would seem to be the spiritual center of town. That’s not just on account of it being the most prominent building you see as you cross the railroad tracks, but because it’s now the Engle Country Church featuring “bible preaching and gospel singing” at 10 AM on the third Sunday of every month. Conveniently, there are some vineyards being tended nearby, too, in case the supply of wine runs low.

Not many original buildings stand, but one, the old schoolhouse, occupies what would seem to be the spiritual center of town. That’s not just on account of it being the most prominent building you see as you cross the railroad tracks, but because it’s now the Engle Country Church featuring “bible preaching and gospel singing” at 10 AM on the third Sunday of every month. Conveniently, there are some vineyards being tended nearby, too, in case the supply of wine runs low.

has contributed a very interesting photo postcard. Postmarked from Engle to Mrs. Anna Martin of

has contributed a very interesting photo postcard. Postmarked from Engle to Mrs. Anna Martin of