I was reading the Onion the other day and there was a quote from a guy named Robert Warshow regarding film noir. He said that film noir allows an audience to "say 'no' the the culture's pervasive 'yes.'" I liked that so much I thought I might make it my New Year's resolution. Say "no" to Britney Spears and Ben Affleck. Say "no" to a recycled identity based on the things you buy. Say "no" to boring old men who can only justify their outmoded beliefs and actions through outrageous lies. And, good grief, let's start looking for something else in 2005. On the other hand, sometimes it's good to say "yes" when someone (or something) says "no." And so it is that we're back at the Clearwater Mill in the Horse Creek Valley, SC.

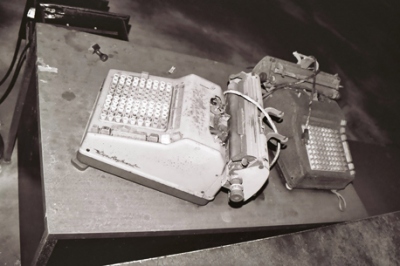

It's hard to believe there was ever a time when people felt a certain loyalty to the companies they worked for. No doubt, companies have no one but themselves to blame for that state of affairs. But those that worked the textile mills in the Valley were fiercely loyal. L. C. "Chick" Thomas, personnel director of the Graniteville Mill (or, the "Big G," just down the road from Clearwater), about 1975: "What's happened to the feelings of our people toward the flag of this country? Toward their government? They've changed. What do you think Watergate did to this country? But I'll tell you this, you find any man around here who's worked for Graniteville Company ten years or more and ask him, if he had the same job somewhere else, would he go to it? He will tell you no, nine times out of ten." All quotes in this post are from this website, the only real first-person record of mill life I could find, with credit to Richard Pearce and the Alicia Patterson Foundation. This is a photo of what remains of the first floor bathroom at the Clearwater.

In fact, the longest record of continuous service by an industrial worker was set at the Graniteville Mill. James Wesley Rearden began work with the Graniteville Company in 1872 at age eleven and continued on until his death in 1959, 87 years later. That record may still stand to this day. Ansel Thompson was also dedicated to his job: "In the fall of 1941 I went on seven days a week and worked seven days a week until I retired in 1970. I never did get a vacation in 28 years. Never a whole week at a time. During vacation time when everybody else was taking theirs, they needed me on my job. And I did stick with them, and I can say it paid off. But it was awful hard. If I'd have had my way, there was several times that I would have been on a vacation with my family because my wife was off work. But I had to work on...I can still remember just as clear as day what that first pay check was. $2.52 a week."

The huge machines used to work the textiles remain in the mill, dusty and forgotten, a scene unfathomable a generation before. Ollie Whittle, an African-American women who started in the Graniteville Mill at age 17: "I was the first colored woman they hired in that mill. I went to the mill in 1917 when they wasn't no men. Uncle Sam had the men. You know what I did once? One time I didn't have a job, so when Monday morning come I just walked right up into that mill with my mop and pail and started scrubbing out the alleys you know between the machines. I worked Monday all day, then Tuesday, Wednesday. On Thursday the Second Boss come on, and he thought the First Boss had hired me. And the First Boss thought the Second Boss had hired me, And there I was just working away. I was smart then. I wouldn't say nothing to nobody. Thursday morning, 'Ollie, how long you been here?’ ‘Oh man, don't you come asking me. I been here ever since Monday morning. And don't you get my time wrong neither cause I’ll tear up this mill. I been here ever since Monday morning.' And I had been there since Monday morning, but nobody didn't hire me. I just went up there and went to work."

Work at the mill was tough, no matter what your job, and the pay low at what was the only real game in town. In addition, accounting practices could get creative. Ms. Whittle: "I used to work ten hours a day, five days and a half a week, go to work Monday morning and knock off Saturday dinner and get my envelope. Wouldn't be but six dollars and five cents. And you know a lot of times the boss didn't send in no social security for you. Well, he’d tell you he was taking it out, but you didn’t know. Then when you get out of a job and want to draw your compensation, you don't have it. You know, they got me charged up with three different numbers, and all the good numbers where I made the most time they say belong to someone else. I just don't know."

Miss Whittle goes on to tell about how, when buying canned tobacco at the local white-owned grocery, blacks had to be refer to it as "Mister Prince Albert." She found calling a can "mister" insulting and refused to do it. She also directed some of that indignant anger toward the mills: "You know they wouldn't want a fool like me in those mills nowadays anyway. 'Cause I tell you what's right and what's wrong and stick to it. I don't care nothing about your Gatling guns, machine guns, your National Guard, or nothing else. But I ain't got time to stir up nothing now. All I want is a living. I ain't looking for the killing 'cause God gonna do that."

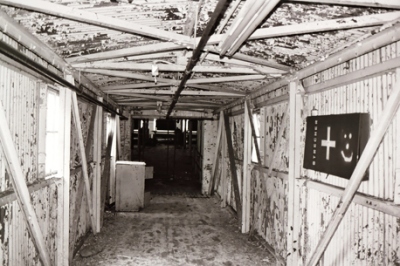

The Clearwater Mill is massive, and on the upper floor little bridges led from one area to another. These are wooden bridges and we crossed them very gingerly indeed, so as not to need that first aid box tacked to the wall. Reverend Cecil Bearden, who at one time ran the orientation program for the Graniteville Mill, said something to his new employees that is pertinent to urban exploration, as well as life in general, really: "You're gonna make some decisions out there, some good ones, some bad ones. Those good ones gonna put jingle in your pocket, those bad ones gonna put tears in your eyes."

This door on the third floor opened out to provide a nice view across Horse Creek Valley, the mills mostly gone quiet now. Miss Whittle, one last time: "Wash, iron, tend to the baby, and rake the yard. If they didn’t have no baby, you carried dinner to the mill. We were their servants. They were poor folks. You can be sure the big shots’ wives didn't work in no mill, like the Supers' wives. But these little poor factory people that worked in the mill, they had to work. They had to get somebody to stay there with those children and work for them. Somebody had to do it. These people wasn’t paying nothing because they wasn't making nothing." And I'm not quite done with the Clearwater Mill yet. Next time we'll close the door, head back inside, and roam around a little more.

2 comments:

I am Cecil Bearden's daughter and he would have been proud what you posted on here. Thanks so much.

Thank you very much for your comment, Ms. Bearden. I'm pleased to hear that your father would've been proud of the post. I'm once again reminded of how much history there is surrounding the Horse Creek Valley and how much of importance occurred there. It's worth remembering and re-telling these stories. Very Best, JM.

Post a Comment