Despite having many more tales from the Cumberland Plateau I have clearly not been posting much lately. Sometimes life can get in the way of blogging, which is good. Remember life? Back before everyone sat in front of glowing screens with buttons in their ears or talked on little plastic phones all day? No, I didn't think so. Anyway, while I like writing I don't particularly like computers and, now being one of those people that spends eight hours each day fighting with one, I'm not getting much up here. But I will! I promise! I think! I even have some things I wrote in real-time, as the disasters were occurring. However, at the moment I'm bound to be off to the UK for a few weeks to return in the New Year. The accompanying photo of the Louisville and Nashville building was taken one warm and quiet fall evening here in Knoxville. I'm not sure how much longer I'll be in Knoxville and I seem to be painting myself into (another) corner (again). But I would love to actually get around to doing a little bit on this town. So, we'll see. Otherwise, have a Merry Christmas and Happy New Year and I'll be back in 2007. John.

Despite having many more tales from the Cumberland Plateau I have clearly not been posting much lately. Sometimes life can get in the way of blogging, which is good. Remember life? Back before everyone sat in front of glowing screens with buttons in their ears or talked on little plastic phones all day? No, I didn't think so. Anyway, while I like writing I don't particularly like computers and, now being one of those people that spends eight hours each day fighting with one, I'm not getting much up here. But I will! I promise! I think! I even have some things I wrote in real-time, as the disasters were occurring. However, at the moment I'm bound to be off to the UK for a few weeks to return in the New Year. The accompanying photo of the Louisville and Nashville building was taken one warm and quiet fall evening here in Knoxville. I'm not sure how much longer I'll be in Knoxville and I seem to be painting myself into (another) corner (again). But I would love to actually get around to doing a little bit on this town. So, we'll see. Otherwise, have a Merry Christmas and Happy New Year and I'll be back in 2007. John.

Thursday, December 14, 2006

(Another) Intermission

Despite having many more tales from the Cumberland Plateau I have clearly not been posting much lately. Sometimes life can get in the way of blogging, which is good. Remember life? Back before everyone sat in front of glowing screens with buttons in their ears or talked on little plastic phones all day? No, I didn't think so. Anyway, while I like writing I don't particularly like computers and, now being one of those people that spends eight hours each day fighting with one, I'm not getting much up here. But I will! I promise! I think! I even have some things I wrote in real-time, as the disasters were occurring. However, at the moment I'm bound to be off to the UK for a few weeks to return in the New Year. The accompanying photo of the Louisville and Nashville building was taken one warm and quiet fall evening here in Knoxville. I'm not sure how much longer I'll be in Knoxville and I seem to be painting myself into (another) corner (again). But I would love to actually get around to doing a little bit on this town. So, we'll see. Otherwise, have a Merry Christmas and Happy New Year and I'll be back in 2007. John.

Despite having many more tales from the Cumberland Plateau I have clearly not been posting much lately. Sometimes life can get in the way of blogging, which is good. Remember life? Back before everyone sat in front of glowing screens with buttons in their ears or talked on little plastic phones all day? No, I didn't think so. Anyway, while I like writing I don't particularly like computers and, now being one of those people that spends eight hours each day fighting with one, I'm not getting much up here. But I will! I promise! I think! I even have some things I wrote in real-time, as the disasters were occurring. However, at the moment I'm bound to be off to the UK for a few weeks to return in the New Year. The accompanying photo of the Louisville and Nashville building was taken one warm and quiet fall evening here in Knoxville. I'm not sure how much longer I'll be in Knoxville and I seem to be painting myself into (another) corner (again). But I would love to actually get around to doing a little bit on this town. So, we'll see. Otherwise, have a Merry Christmas and Happy New Year and I'll be back in 2007. John.

Tuesday, November 28, 2006

Hamilton County, May 2006 (Part I)

It is the end of May when somehow, miraculously, we finish surveying Aetna Mountain. For the last week we have had a four-person crew, but Carl is due to leave on a two-month trip to Chile in a couple days, so we will drop back to three people. Allison, who has been feeling worse and worse as the days have gone on, has finally gone to see a doctor and has been told that she’s suffering from a severe allergy to something she’s encountered in the forest. The doctor prescribes steroids and tells her she can come back to work. It doesn’t occur to me right off the bat that the doctor has no idea what he’s talking about, but it will soon enough.

Carl is still with us as we do our initial recon of our first Hamilton County site. After Aetna Mountain we figure things have to get easier. We will figure something like this after completing each county and we’ll be wrong every time. Just finding the site is a piece of work. The roads we need are either not on our Tennessee Gazetteer or named something different on the maps than the actual street signage would indicate. Our forestry maps, on the other hand, show logging roads that may no longer exist or may be so treacherous as to be impassable. Of course, there’s no way to determine if a logging road is impassable other than driving down the thing and hoping you’ll notice your impending doom before it’s too late to turn back. But at this point we’re just trying to wind our way through a labyrinthine set of neighborhood roads that turn back and forth in every direction, now seemingly leading us to our destination, now leading us away. We make wrong turns and follow roads to their abrupt ends. We use our GPS machines and compasses to try to stay on course, but these tools are most helpful when we can travel as-the-crow-flies, something we can’t even come close to doing at the moment. People stop what they’re doing and watch us pass, wondering why someone they don’t know is driving down their street. At times like this we’d be hard put to answer them in a way that didn’t sound crazy. At one point we go under a bridge that would seem to lead to our destination, but there is no obvious way up to the bridge. It sits wholly unused above us, apparently coming out of nowhere and almost certainly leading there as well.

Finally, we emerge from a series of roads that have taken us everywhere but straight ahead. We pass a ramshackle barn and a shed filled with old car parts. Ahead of us is the mysterious bridge, a bridge that, while constructed of poured concrete like any highway overpass, appears to serve no function but to drop us onto a deeply rutted dirt road. Then immediately the scene begins to look like home. To the east the landscape drops away and trees stretch out into the distance. A now-familiar queasiness wells up in the belly as the terrain that has to be walked is assessed. This area is more remote than Aetna Mountain, a lost forest tract that we might never be found in, no matter how many helicopters and search dogs were brought out. Some of the transects we need to walk are short; others are over a mile long. There isn’t a cloud in the sky and the day is only beginning to hint at the heat to come later in the summer. Carl laughs and shakes his head, making no secret of the fact that he’s looking forward to getting out of this job and getting to Chile, where it’s surely much safer. We pass a strange house sitting silent at the bottom of a hill. The home looks fairly nice and is surprisingly large but there has clearly been no activity anywhere near it for some time. Along the road sits a dust-covered van and it is anyone’s guess as to why someone chose to build out here. The owner of the house may have driven his van up months ago and promptly died--stroke, heart attack, murder--and no one would ever know. We’re not about to look into it.

We’ve spent so much time trying to find our location that there isn’t much time to survey, so we choose some of the shorter transects and get a taste of what we’re in for; steep hills banked by hemlock and pine beetle kills ringed by blackberry bramble. As what he thinks will be his last act as a forest surveyor, Carl jogs a couple transects to polish off a remote corner. We don’t know yet that we’ll be down to a two-person crew in a matter of days and Carl will eventually find himself back in the woods. We finish up and head back to Knoxville, finally calling it a week, but quickly find that one of the roads we came in on has been torn up over the last couple hours and our path is now blocked by a bulldozer and several dump trucks. We wait some time for the crew to acknowledge us and then wait a little longer for the dozer to grade us a path out. It seems that for the duration of the summer no road will ever be certain.

The first photo is a shot of Kelly's Inn, our home in Dayton, TN until we depleted our travel budget and had to start sleeping on air mattresses at a wildlife refuge. The second shot is a rare appearance of your hapless host and, while taken in Hamilton County, it's not the site described above. I could've saved it for a more appropriate post, but I was kinda in the mood to post it. Note the GPS machine in my left hand--the coordinate we needed to find was above me, on top of all that rock. Fun! We'll get to that later. The last shot is of Young Rd., the torn up street I mentioned. Since I had a couple minutes right then I figured I'd snap a shot.

Wednesday, November 15, 2006

Marion County, May 2006 (Part VIII)

Carl and I come to the edge of a thicket of raspberry brambles. It’s been rough going for the last couple hundred meters and we are covered in small cuts from the thorns of the bushes. The sweat makes the wounds sting. Our pants have been torn. It’s seems like a mistake in navigation was made at some point but we can’t figure out exactly where. As the brambles finally give way we find ourselves standing on the edge of a large hunting camp. Ahead of us is a green school bus up on blocks, the windows spray-painted black. A huge stars ‘n’ bars hangs across the front of the bus. Sometimes you come upon places that just feel unsettling and unsafe and you want to get away as quickly as possible by the closest means at hand. “I don’t really want to go through this,” says Carl, looking from one end of the camp to the other. This coming from an avid hunter who has struck up jovial conversations with every sportsman we’ve come across. He calls it the “brotherhood of hunters” but apparently doesn’t feel too fraternal with whoever has set up this imposing camp. I look out at the array of shacks and decrepit cars. I see a well with a memorial to a dead man chiseled into the front of it. A barbeque pit. Ropes hanging from trees. Burnt logs. I don’t want to go through it either. I look behind us at three hundred meters of dry raspberry thicket and dead pine trees. “We can’t go back the way we came,” I say. We wait. A tattered plastic tarp flaps in the slight breeze. What looks to be an old flag pole stands in the middle of the clearing. There doesn’t seem to be anyone around.

Carl and I come to the edge of a thicket of raspberry brambles. It’s been rough going for the last couple hundred meters and we are covered in small cuts from the thorns of the bushes. The sweat makes the wounds sting. Our pants have been torn. It’s seems like a mistake in navigation was made at some point but we can’t figure out exactly where. As the brambles finally give way we find ourselves standing on the edge of a large hunting camp. Ahead of us is a green school bus up on blocks, the windows spray-painted black. A huge stars ‘n’ bars hangs across the front of the bus. Sometimes you come upon places that just feel unsettling and unsafe and you want to get away as quickly as possible by the closest means at hand. “I don’t really want to go through this,” says Carl, looking from one end of the camp to the other. This coming from an avid hunter who has struck up jovial conversations with every sportsman we’ve come across. He calls it the “brotherhood of hunters” but apparently doesn’t feel too fraternal with whoever has set up this imposing camp. I look out at the array of shacks and decrepit cars. I see a well with a memorial to a dead man chiseled into the front of it. A barbeque pit. Ropes hanging from trees. Burnt logs. I don’t want to go through it either. I look behind us at three hundred meters of dry raspberry thicket and dead pine trees. “We can’t go back the way we came,” I say. We wait. A tattered plastic tarp flaps in the slight breeze. What looks to be an old flag pole stands in the middle of the clearing. There doesn’t seem to be anyone around.  We gingerly step out of the bushes and start across the camp. The shacks stand in lines along a dirt road that we quickly cross. Beer cans crushed on the ground. I want to stop and take a picture but something feels wrong and instead I start walking faster. As we reach the far side a jeep turns onto the dirt road and I trot the last twenty feet to the woods. Carl is behind me and a few seconds later we’re both well into the trees. As far as we know, the man in the jeep did not see us. Months will pass before in casual conversation I mention this odd camp to a colleague of mine familiar with the area. “Oh,” he replies. “You want to stay away from there. They don’t like anyone near them and aren’t afraid to prove it. They aren’t even supposed to be up there but no one can get them down.” Yet another disaster amongst a seemingly endless string has been narrowly averted this day.

We gingerly step out of the bushes and start across the camp. The shacks stand in lines along a dirt road that we quickly cross. Beer cans crushed on the ground. I want to stop and take a picture but something feels wrong and instead I start walking faster. As we reach the far side a jeep turns onto the dirt road and I trot the last twenty feet to the woods. Carl is behind me and a few seconds later we’re both well into the trees. As far as we know, the man in the jeep did not see us. Months will pass before in casual conversation I mention this odd camp to a colleague of mine familiar with the area. “Oh,” he replies. “You want to stay away from there. They don’t like anyone near them and aren’t afraid to prove it. They aren’t even supposed to be up there but no one can get them down.” Yet another disaster amongst a seemingly endless string has been narrowly averted this day. Not photos of the camp, the top being a cave in the Sequatchie Valley and the second a strange marker in the Hinds Valley Baptist Church and Cemetery, 1800-1946. Apparently Tennessee died sometime over that 150-year period and was buried with a cheap headstone.

Wednesday, November 01, 2006

Marion County, May 2006 (Part VII)

It’s Jason’s second day on the job. We’re working lower on Aetna Mountain, skirting a neighborhood known as the “Devil’s Poket” (sic) in Whiteside, TN. The neighborhood is comprised of nothing more than one dead end street located nearly at the bottom of the mountain, merely a small notch of land cut out of the surrounding timber holdings. There are about eight houses on the street. One is a trailer that has been burnt to the ground, only its steel support beams remaining intact, rusting out of the melted debris. A second house looks habitable from the street except that “No Trespassing! Private Property!” is spray-painted across the front in big, black letters. From behind it can be seen that the roof of the house has caved in, the backyard littered with shingles and splintered 2”x 4”’s. The home nearest the outlet of the street is flying a massive stars ‘n’ bars on a pole in the front yard. Railroad tracks run just beyond and when a train stops, as will happen soon enough, there is no way in or out of the neighborhood.

It’s Jason’s second day on the job. We’re working lower on Aetna Mountain, skirting a neighborhood known as the “Devil’s Poket” (sic) in Whiteside, TN. The neighborhood is comprised of nothing more than one dead end street located nearly at the bottom of the mountain, merely a small notch of land cut out of the surrounding timber holdings. There are about eight houses on the street. One is a trailer that has been burnt to the ground, only its steel support beams remaining intact, rusting out of the melted debris. A second house looks habitable from the street except that “No Trespassing! Private Property!” is spray-painted across the front in big, black letters. From behind it can be seen that the roof of the house has caved in, the backyard littered with shingles and splintered 2”x 4”’s. The home nearest the outlet of the street is flying a massive stars ‘n’ bars on a pole in the front yard. Railroad tracks run just beyond and when a train stops, as will happen soon enough, there is no way in or out of the neighborhood.For sometime we have been hearing gunshots. We’ve assumed that someone is hunting birds or getting in a little target practice. Jason and I split off from Carl and the shots become louder now as we come up just behind the neighborhood. Carl has continued on through the woods, but the coordinate were tracking seems to put us somewhere smack dab in the middle of the Devil’s Poket. Rather than stumble through backyards, we opt to cut down onto the road. For a few minutes the shooting ceases.

We enter the neighborhood and pass a woman and child. They appear to be doing some yard work but as we get closer it’s hard to tell if the property they’re tending is abandoned or not. We wave hello and the woman waves back, then quickly crosses the street with the child and enters another home. Now our GPS unit indicates that our point is actually in the backyard of the house at the end of the block. We have no intention of going into anyone’s yard, but figure we can get close enough from somewhere on the street. Of course, we look ridiculous with all our gear. Soaking with sweat and filthy, holding a GPS unit in one hand and a compass in the other, I spot two people watching us from the top of a driveway near the end of the street. For a moment I consider whether to go up to them and explain what we are doing, but something just doesn’t feel right and so we decide to keep moving through the neighborhood, picking up our pace a bit. Suddenly there’s a crack and a bullet cuts through the trees about 20 feet away. A few more shots are fired before we can take cover behind a row of twenty or so strange brick ovens that have been filled with trash. It’s possible these ovens are the remnants of a coke operation decades previous or maybe they were built when Aetna Mountain was being heavily mined for coal. Whatever the case, they are now protecting us from the residents of Devil’s Poket.

We enter the neighborhood and pass a woman and child. They appear to be doing some yard work but as we get closer it’s hard to tell if the property they’re tending is abandoned or not. We wave hello and the woman waves back, then quickly crosses the street with the child and enters another home. Now our GPS unit indicates that our point is actually in the backyard of the house at the end of the block. We have no intention of going into anyone’s yard, but figure we can get close enough from somewhere on the street. Of course, we look ridiculous with all our gear. Soaking with sweat and filthy, holding a GPS unit in one hand and a compass in the other, I spot two people watching us from the top of a driveway near the end of the street. For a moment I consider whether to go up to them and explain what we are doing, but something just doesn’t feel right and so we decide to keep moving through the neighborhood, picking up our pace a bit. Suddenly there’s a crack and a bullet cuts through the trees about 20 feet away. A few more shots are fired before we can take cover behind a row of twenty or so strange brick ovens that have been filled with trash. It’s possible these ovens are the remnants of a coke operation decades previous or maybe they were built when Aetna Mountain was being heavily mined for coal. Whatever the case, they are now protecting us from the residents of Devil’s Poket.The shots keep coming and I radio Carl, still using the handles we’ve developed in reference to our cheap radio brand, Cobra. “Cobra Two, Cobra One has come under fire and has sought shelter. Please hold your position.” Carl comes back quickly: “I’m on the ground. I hit the dirt as soon as I heard that first round.” It sounds like he’s started laughing. “I’ll lie here until you’re clear.”

We follow the ovens down to the railroad tracks. They can’t hit us at this angle, but we can still hear the gunfire. We skirt the tracks, hop a dirty, trash-filled creek, and head deeper into the woods, finally lining ourselves up with the proper transect. The shots sound further away and finally stop altogether. I radio Carl and tell him we’re safe and he continues on his way. As we walk on Jason and I discuss what’s just happened. “They probably weren’t trying to hit us,” he says. “Just scare us a little. Besides,” he continues, “It sounded like a .22. At that distance it just would’ve stung a little.” I knew right then that I’d hired the right person for the job. And we’d have to come back the next day.

That top shot isn't actually from Aetna Mountain, but was taken at the head of a driveway near Cagle Mountain in Sequatchie County. The second shot is also from Sequatchie County, but the third is out the back porch of the check-in station at the Hiwassee Wildlife Refuge, Birchwood, TN.

Monday, October 23, 2006

Marion County, May 2006 (Part VI)

We’ve added another member to the crew, Jason, and his first day is a tough one. The haul up the first mountain is long and steep. Then we go back down. Then we start back up again. I walk a bit ahead and as the day progresses my lead increases. Jason is a smoker, but assures me that within a week he’ll be “battle hardened”; little do we know that it won’t take him nearly that long. As we start our final ascent of the day Jason stops and gasps, “I’ve gotta take a fiver.” I’m about 40 feet in front (and 20 feet above) him, so I sit on a nearby rock and wait. I’m not concerned. I figure he’ll do okay--at least as well as anyone else could be expected to do.

After a few minutes we start up again. When we reach the top of the mountain Jason looks a little peaked. I almost feel a pang of worry, but it quickly passes. The concern I feel for Allison, on the other hand, is steadily growing. She has developed a rash on the back of her leg and has been having trouble sleeping. She’s also been having headaches and experiencing joint pain. I’ve told her that she needs to get checked for Lyme disease as soon as we get back to Knoxville. She's replied, with all the confidence she can muster, that she knows she doesn’t have Lyme disease and will be fine. I ask her to go anyway. In the meantime, we’ve given her the easiest transects, usually the ones closest to the vehicle. On this day, therefore, she’s finished long before us and has been sleeping in the bed of the truck for the last couple hours.

After a few minutes we start up again. When we reach the top of the mountain Jason looks a little peaked. I almost feel a pang of worry, but it quickly passes. The concern I feel for Allison, on the other hand, is steadily growing. She has developed a rash on the back of her leg and has been having trouble sleeping. She’s also been having headaches and experiencing joint pain. I’ve told her that she needs to get checked for Lyme disease as soon as we get back to Knoxville. She's replied, with all the confidence she can muster, that she knows she doesn’t have Lyme disease and will be fine. I ask her to go anyway. In the meantime, we’ve given her the easiest transects, usually the ones closest to the vehicle. On this day, therefore, she’s finished long before us and has been sleeping in the bed of the truck for the last couple hours.As Jason stumbles wearily up the dirt road I see Carl on a deer stand—more like a deer platform—that someone has built way up in a high-tension tower. He waves and it looks like he’s having fun, so I stop and once he comes down I go up. At the top the platform (a piece of wood simply laid across a corner angle) is small and the footing precarious. It’s a very long way down. I wonder for a moment what hunter would be crazy enough to sit up here with a gun waiting for a deer to pass by below. Then I quickly realize there’s plenty of ‘em. Hell, now I’m up here too.

Alright, there's a little photo trickery here. The first and third shots are from Hamilton County, not Marion. That middle photo is from inside a coal mine in Sequatchie County. Did you know you can die from going in old coal mines? The culprit is known as "black damp." We'll get to that later.

Tuesday, October 17, 2006

Marion County, May 2006 (Part V)

“We’re drillin’”, the man says, and a jet of muddy tobacco juice spews from his crooked mouth and lands at his feet. The statement is wrong on any number of levels. We’ve pulled beside a well-punching rig and four or five tough-looking customers are standing around. Their pick-up trucks are in the road and one of the larger ones is completely blocking our path. The men are smoking, talking, staring at the ground, but certainly not drillin'. Frankly, we don’t care what they do, as long as they let us by. But, so far, “We’re drillin’” is all anybody will say to us. So we wait in the idling truck and look at each other, wondering how this will play out.

As it happens, it plays out rather prosaically when, after a couple minutes of nothing much, an older man finally breaks away from the group and moves the truck from the road. We wave slightly as we pass and I watch in the rearview mirror as the men re-group. Carl resumes navigating.

Not many days afterward we meet Ricky, one of the drilling team, as he’s driving up a dirt road that we’re using to start that morning’s surveys. He gives us his cell phone number in case we need help—this has become a running theme—and tells us that at the very top of Aetna Mountain lives a family with two teenaged daughters. “They have no electricity,” he says. “How they get their water is anyone’s guess.” On top of the mountain is a long way from anywhere; there certainly aren’t any neighbors to get in the way. For the rest of our time in this place we will hope for a glimpse of what quickly becomes known as the “unknown family.” We believe that we see the mother and father on two occasions going slowly up the mountain in their red S-10. They do not seem happy to see us on either encounter. But it is the daughters we really want to run across, mountain nymphs tripping through dewy meadows in luminescent nightgowns. Perhaps chasing a fawn through the woods as they dance and sing, wildflowers wound into their flowing tresses. Certainly these Southern sirens would lead well-drillers and forest surveyors alike to their ultimate doom. Well, it does get tedious walking through the woods everyday and the mind tends to wander.

Not many days afterward we meet Ricky, one of the drilling team, as he’s driving up a dirt road that we’re using to start that morning’s surveys. He gives us his cell phone number in case we need help—this has become a running theme—and tells us that at the very top of Aetna Mountain lives a family with two teenaged daughters. “They have no electricity,” he says. “How they get their water is anyone’s guess.” On top of the mountain is a long way from anywhere; there certainly aren’t any neighbors to get in the way. For the rest of our time in this place we will hope for a glimpse of what quickly becomes known as the “unknown family.” We believe that we see the mother and father on two occasions going slowly up the mountain in their red S-10. They do not seem happy to see us on either encounter. But it is the daughters we really want to run across, mountain nymphs tripping through dewy meadows in luminescent nightgowns. Perhaps chasing a fawn through the woods as they dance and sing, wildflowers wound into their flowing tresses. Certainly these Southern sirens would lead well-drillers and forest surveyors alike to their ultimate doom. Well, it does get tedious walking through the woods everyday and the mind tends to wander. I wonder what the unknown family does in the winter when the roads get icy and there’s no way down the mountain for days at a time. Ricky shakes his head mournfully. “I just hope those girls survive,” he says. “I just hope they can make it through.”

Well, so much for one post a week. I won't make promises like that again since I know I can't keep 'em. I guess I'll just post when I can. I am an irresponsible blogger.

Monday, October 02, 2006

Marion County, May 2006 (Part IV)

“We can’t go forward! We can’t go down! We can’t go up! We can only go back!” My radio call to Carl captures our predicament fairly succinctly. Above us is a series of vertical bluffs. In front of us is a waterfall. Below us is a steep drop to a rocky creek. Allison is annoyed, but can hardly argue with my assessment. Carl just laughs and wishes us luck; he’s already on top of his own set of bluffs. Defeated, we begin the long ascent up the valley, back the way we came.

Later we go to Lookout Mountain for dinner at the Lookout Mountain Café. Afterwards we go to Point Park, but since we can’t scrape together the $6 entrance fee between the three of us, we have to turn around. A representative of the National Park Service has been watching us from his truck, lest we jump the gate. As we pass his vehicle he asks us what we’re doing in the area, a presumptuous question. At first he doesn’t believe us when we tell him we’re walking Aetna Mountain. He laughs and asks if we’re using the trails. We tell him, “No, we just go in and start walking.” He laughs again and asks us how far down we go. “All the way to the bottom,” we reply, “to the creek beds.” He stops and raises his eyebrows, suddenly serious. “Really?” he says. “Let me give you my card.”

Donald “Cavewolf” Connor moved to Chattanooga for the caves. He tells us he does 300 foot drops in caves, sometimes spending nine hours in the descent. He also dives, though he will not enter totally submerged caverns. He asks us if we’ve seen any caves, but we have not. He says we might come across a “blower,” a cave that funnels air from the ridge down to the valley floor. Air velocity can reach 30 mph and he says we can’t miss one of these things if it’s close. “You’ll feel the wind.” The Chattanooga area apparently has the highest density of caves in the US and Cavewolf would love to know about any we stumble across. Also, it turns out that he’s a member of Chattanooga Cave Search and Rescue and offers us his services if we get stuck. It’s reassuring and not reassuring at all.

Donald “Cavewolf” Connor moved to Chattanooga for the caves. He tells us he does 300 foot drops in caves, sometimes spending nine hours in the descent. He also dives, though he will not enter totally submerged caverns. He asks us if we’ve seen any caves, but we have not. He says we might come across a “blower,” a cave that funnels air from the ridge down to the valley floor. Air velocity can reach 30 mph and he says we can’t miss one of these things if it’s close. “You’ll feel the wind.” The Chattanooga area apparently has the highest density of caves in the US and Cavewolf would love to know about any we stumble across. Also, it turns out that he’s a member of Chattanooga Cave Search and Rescue and offers us his services if we get stuck. It’s reassuring and not reassuring at all. Cavewolf tells us some other things, including his belief that the listing of mountain skullcap as a federally threatened species is an abuse of the Endangered Species Act. He says that a guy he knows got it listed just to see how easily it could be done. “That plant is everywhere!” Cavewolf spits and we laugh. We haven’t seen a single Scutellaria montana and all we do is look for the thing. We’ve only come as close as its brother, Scutellaria pseudoserrata. Soon, however, we will see evidence that Cavewolf may have been correct.

Cavewolf tells us some other things, including his belief that the listing of mountain skullcap as a federally threatened species is an abuse of the Endangered Species Act. He says that a guy he knows got it listed just to see how easily it could be done. “That plant is everywhere!” Cavewolf spits and we laugh. We haven’t seen a single Scutellaria montana and all we do is look for the thing. We’ve only come as close as its brother, Scutellaria pseudoserrata. Soon, however, we will see evidence that Cavewolf may have been correct.Over the next couple of weeks we find a few small cave openings, but we don’t tell Cavewolf. Technically, we shouldn’t encourage others to trespass on the property. In any case, we never do find a “blower.” But we never have to call Chattanooga Cave Search and Rescue either.

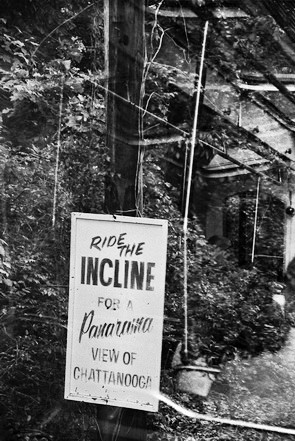

That's a view over Chattanooga at the top and a shot of the inclined railway that can take you there. At the bottom is the real mountain skullcap.

Sunday, September 24, 2006

Marion County, May 2006 (Part III)

We’ve misjudged our distances. Badly. Now it’s 7:30 PM and we’ve been out so long the high-tech rechargeable batteries in our GPS machines are dying. Allison starts to feel weak and has to sit down on a rock. She doesn’t think she can continue without food and neither of us has anything left to eat. Worse, we’re at least an hour from the truck. I radio Carl: “Do you have any food?” There’s a pause, the situation being analyzed and understood. “I have some crackers.” “Can you get those to us?” Another pause. A little longer. “Yeah, I think so. Where are you?” I laugh grimly as I tell him.

Ten minutes later Carl has tossed down some crackers which I’ve given to Allison. He’s standing about forty feet above me and has already had to jump some wide chasms to get to us. We walk back and forth along the huge bluff, him above and me below. There is simply no easy way down. We scout out little ledges, possible hand or foot holds. When we’ve come up with the best line we can find, Carl starts to climb down. I quickly realize that he probably should’ve tossed me his backpack before starting. Now I can only hope it doesn’t get snagged on a limb. He has to drop the last seven feet or so, but everything goes well.

After Allison eats the crackers we start the one kilometer walk. One thousand meters goes pretty quick on pavement, but in this terrain we just hope to get out before dark. We know we’re near the truck sometime later when we pass what we thought earlier might have been a meth lab, a beat-up shack with two hoses leading from the rear up into the creek. On the way in we heard someone rummaging around out front, but this time we do not. We’re thankful as encountering drug activity would be a bit of a problem. Nothing is worse than having someone know that you know something they don’t want you to know, especially when that something could put them in prison. We don’t find a meth-maker, but we don’t find my sunglasses either; I’d lost them that morning and thought we might run across them on the way back. Over the weekend I’ll buy a new pair and promptly run them over at 7:30 AM on Monday, a $50.00 error.

Sunday, September 17, 2006

Marion County, May 2006 (Part II)

Untold tangles of catbriar, forests of poison ivy, and dozens of wood ticks conspire to convince Allison to wear long pants and boots. But it won’t be long before she’s moved to upgrade her gear yet again. As we set off over Aetna Mountain I’m showing Allison how to use the GPS unit, navigate the terrain, and look for endangered plant species, all at the same time. We come to a particularly steep area that leads to a creek bottom and I start to head down feet first, using my hands to steady myself. I am just about to move my hand to a spot slightly below me when I catch a glimpse of something that sends me scooting back up the bank yelling “Whoa! Whoa! Whoa!” In the exact spot where I was going to put my hand a copperhead lays nestled in the leaves. The snake’s coppery markings blend in perfectly with the fallen leaves and I'm lucky I didn’t miss seeing it. It’s doubly lucky because the snake wasn’t going to miss me. Usually docile and shy, this particular copperhead was reared up and ready to defend itself. After getting out of harm’s way I open up my backpack, grab the camera, and snap a few photos. All the while the snake maintains its aggressive posture. I watch the snake a while longer and make a mental note to buy snakebite kits for everybody. (The kits would be largely for psychological rather than practical reasons. Has anyone ever actually been saved by a store bought snakebite kit? The instructions state that the venom extractor must be applied to the bite within one minute. Good luck.) We slowly make our way down to the bottom of the ravine, giving the snake a wide berth and watching our handholds, not knowing that the fun has just begun.

About half an hour later we come to a dry creek bed that runs down slope. I climb down a short incline and onto the rocks and make my way across. Suddenly I hear Allison gasp behind me. Then she screams, “Oh my God! Oh my God!” I turn around and see that she’s backed up against the bank, which is too steep to easily climb back up. I’m about to ask what’s wrong when she points to the rock ledge not two feet away from her. Then I hear the rattle. It’s a timber rattlesnake, perhaps numerous, though rarely seen, and this one wants just as little to do with us as we do with it, only Allison has come very close to stepping on it, an indignity the snake would not have suffered politely. I direct Allison toward a safe path across the creek, keeping one eye on the snake, which has now backed itself up tight under the ledge. Once Allison is across I, of course, get out the camera and take some photos. While a person can walk the woods of Tennessee their whole lives and never see a timber rattlesnake, I’ll see another within the month. Allison has snake boots the following week. Heck, I got some myself.

Monday, September 04, 2006

Marion County, May 2006

In May the work commences in earnest and we have added a third member, Allison, to our crew. We follow I-75 south toward Chattanooga and once beyond that city we dip into Georgia, change time zones, and come back up into Tennessee again very near our destination: Aetna Mountain. At one time the site of a major coal mining operation, Aetna Mountain sits above Nickajack Lake which is formed by an impoundment of the Tennessee River. The interior of the mountain is steep and dangerous, although some of the danger is provided by the residents themselves, as we shall soon see. A meeting earlier in the day produced immediate concern from a forest supervisor familiar with the area. “Are you going here?” he asked, pointing to our map. We replied that we were. “Then please call me each evening when you leave the forest so I know you got out safely. I can’t get to you quickly, but I can at least get to you eventually.” We assume he’s mostly concerned about the terrain, although one member of our crew has already been advised to carry a gun.

Once we reach the mountain we have to decide how to access our survey area. It’s apparent that a piece of private property provides the easiest entrance to our first parcel so we decide to drive down a rutted, gravel road, hoping to find the property owner and hoping that he’ll be friendly. A car begins to descend a steep dirt driveway and when it reaches the bottom we pull off the narrow road to let it pass. Carl, the only native Tennessean amongst us, gets out of the truck to see if these folks own the property or know who does. It turns out that, while they’re not the property owners, they can take us to the man who is, Smitty Brown, a fellow who usually works a roadside produce stand off the highway. In a display of helpfulness and generosity that we will later find throughout Walden’s Ridge and the Cumberland Plateau, the man and his wife tell us that if we follow them they’ll lead us to Smitty’s stand. So we turn around and follow them back to the highway.

The first stand we come to is empty, but we’re told that Smitty has a second stand across the bridge, so we continue on. The second stand is also empty. Our guide apologizes and explains that Smitty must be elsewhere. He suggests we just go on up the steep driveway to Smitty’s place and talk to the residents of the first place we come to; they live on Smitty’s land and can give us permission just as well as Mr. Brown. If Smitty shows up, they’ll be able to tell him why there’s a big state truck in his drive.

We go back to Smitty’s driveway and look up. It really is steep, and rutted too, loose gravel pooling in the deep ruts. Cut-offs and switchbacks have been made here and there but it’s difficult to tell which sections would be best to use. From the bottom, it almost looks too dangerous to drive. Allison gets out of the truck and says she’s not driving up—she’d rather walk. Still, we know people live up there, so it must be possible to get a vehicle to the top. Carl decides he’s going to go for it and drops the truck into 4WD. I get out of the truck to make the hike with Allison, each of us hoping that the Ford F-150 won’t roll down the hill on top of us. We watch the truck crawl up the incline and cross our fingers that Carl chooses the right path up.

It takes us longer to walk, but soon we’re all at the top of Smitty’s driveway, taking in an impressive view of Nickajack Lake, crisscrossed by bridges, the interstate skirting the perimeter. The walk was hot and strenuous and now that the proper route has been established we’ll be taking the truck up each day, assuming we get permission to access the property. We knock on the door of a trailer and a woman answers, clearly surprised to see us. It’s hard to imagine there are many visitors that make it up here unannounced. Once Carl explains our business we’re told that it’s absolutely no problem to park on the property—they’ll tell Smitty what’s up if he returns. Clarence, the man of the house, comes to the door and in the course of our conversation reveals that he has congestive heart failure. This would not seem to be the place to live if one has congestive heart failure. Just getting the mail could kill you. Still, the view from the top of that driveway is something a person could get used to. It might be tough to leave behind. After getting brought up to date on what’s happening at Talladega, we thank the couple for their help and they wish us luck.

We go back to the truck and get our gear together. I notice that Allison is wearing shorts and sandals. “Aren’t you going to at least put on some boots?” I ask, pointing to the thick poison ivy just beyond the truck. “Nah. I’m not allergic and don’t like wearing boots.” By the following week she’ll be wearing the sturdiest pair of snake boots she can find.

I might not get another segment up next weekend as I'll be back in the Midwest. However, I'll be here again in two weeks. I think. Thanks for reading!

Sunday, August 27, 2006

Rhea County, April 2006 (Part II)

As we come up the ridge the fog thickens. Our headlights burn dimly through the milky-white morning and visibility is down to something less than 500 feet. Out of the soup, on the side of the road, a shack takes form then quickly recedes again, like some strange specter. Walden’s Ridge, when the fog is thick, seems to be made of cloud. Or perhaps it is part of the clouds, the massive waves of mist breaking free of the forest and rising up through the trees, rejoining the sky.

But by the time we reach our survey site the fog is burning off and the barren clearcut has come into view. We put on our packs, set our GPS coordinates, and start the walk down the valley toward the creek. Once at the bottom we will start back up again. This will be repeated, up and down, back and forth, until we are out of time or stamina or both.

The work is hard and dangerous, though not as dangerous here as it will become elsewhere. There are sheer bluffs to be scaled and then descended again. The terrain is steep and rocky at best, impassable at worst. Yet the forest, a second or third-growth mix of oak, maple, poplar, and hemlock remains majestic, punctuated by rocky falls and cliffs.

We stop for lunch in a running creek and eat perched on boulders that must have tumbled down into the valley thousands upon thousands of years ago. As we eat I spot an eastern box turtle perched on a ledge of rock, both of its feet hanging over the edge, as if unsure how to proceed. I take my camera out of my pack and begin to photograph the animal, the state reptile of Tennessee. I am pleased that it is holding its unusual pose and soon my partner comes up to take some pictures as well. We discuss angles and compare shots, both laughing at the strange posture of the old turtle. Finally, something occurs to me and I gently prod the turtle with my boot. It does not move. I pick the turtle up and it doesn't withdraw its head nor clamp its shell down tight, as would be normal. It merely blinks at me, slowly and sadly; it is dying.

We stop for lunch in a running creek and eat perched on boulders that must have tumbled down into the valley thousands upon thousands of years ago. As we eat I spot an eastern box turtle perched on a ledge of rock, both of its feet hanging over the edge, as if unsure how to proceed. I take my camera out of my pack and begin to photograph the animal, the state reptile of Tennessee. I am pleased that it is holding its unusual pose and soon my partner comes up to take some pictures as well. We discuss angles and compare shots, both laughing at the strange posture of the old turtle. Finally, something occurs to me and I gently prod the turtle with my boot. It does not move. I pick the turtle up and it doesn't withdraw its head nor clamp its shell down tight, as would be normal. It merely blinks at me, slowly and sadly; it is dying. We return to our lunch, the photos no longer as enchanting. When we are about to move on I leave a bit of apple for the turtle. It moves its head slightly, but that is all. Soon it will be dead. But we have other things to worry about.

Saturday, August 19, 2006

Rhea County, April 2006

As we drive west from Highway 27 I look up at the ridge high above and immediately begin to wonder what I’ve gotten myself into. We cross the railroad tracks and drop down into the flats, black-green with the dense vegetation. The brown, ropy, kudzu vines twisting up and over anything in their path have not yet leafed-yet. Once they do, even more of this already secretive and shadowy land will be obscured.

Off the narrow roads, nestled in the foliage, are homes. Some of the homes are ramshackle, wooden affairs with chipped and peeling paint. Many residences are trailers, some of which seem to be unlivable. The yards are often nothing more than dirt, the grass worn away, with all manner of animals, children, and appliances strewn about. Some are nearly totally obscured by cars, beaten hulks sitting wheel-less on cinder blocks, the various components removed and laid nearby, as if they might somehow be useful once again. In many yards there are fires, and thin wisps of gray smoke waft through the trees as litter and debris smolders. Later I am told that Rhea County is one of the poorest counties in Tennessee. Despite this apparent poverty, most residences have a late model car or truck parked nearby, a sign of the primacy of movement in the modern age, a necessity requiring any cost or privation.

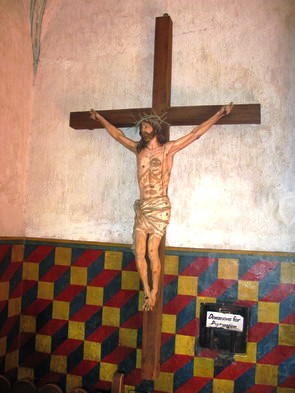

Everywhere there are churches of all denominations and creeds; Evangelical, Pentecostal, Methodist, and, naturally, Baptist. The church buildings are of all shapes, sizes, and conditions, and the sheer number of them makes it difficult to believe there are enough people to support them all. Yet each must have their congregants and outside these places of worship, as well as hung in front of homes and nailed to various trees, there are signs: “Prepare to meet thy God,” Know Jesus, know peace; no Jesus, no peace,” and often simply, “Repent!”

We pass through and begin to climb Walden’s Ridge, the road a steep switchback. Once on top you can see clear across the Tennessee Valley, the river snaking into the distance, the mountains of North Carolina on the horizon. The roads we travel are used by no one save the people who live near them. On top of the ridge are farms, horse lots, and immaculately rendered homes that resemble old-fashioned log cabins. We follow a dirt road alongside a farm, cows watching us from the field adjacent, and pass through a gate. Beyond the gate is a huge clearcut, the ground littered with shattered timber. Small clumps of scrawny, dead snags dot the landscape. It looks as if a bomb has been detonated on this place.

We park the truck at the end of an old logging road and head toward a pocket of live trees, the terrain too steep and rocky for the logging equipment to have accessed. These are the areas we will be walking and from here on out each will seem steeper and rockier than the one previous. It will not be for the last time that I wonder what I’ve gotten myself into.

Sunday, June 18, 2006

A Bloody Battle

Someone wrote me recently asking if I could do a few posts on some of the mountain towns of the South. Since I’m currently living at the foot of the Great Smoky Mountains and spend most days roaming around the Cumberland Plateau, it shouldn’t be a problem to get to a few of those places soon. I was also asked if I could do a bit more on Civil War sites, and that I can do right away. So, without further ado, we’ll visit the Chickamauga Battlefield, just outside of Chattanooga, across the Georgia line, where one of the bloodiest battles of the Civil War was fought.

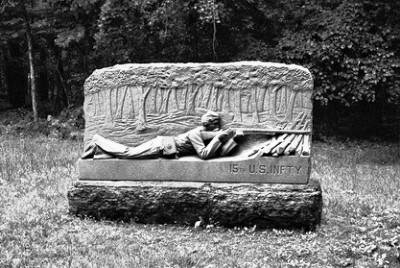

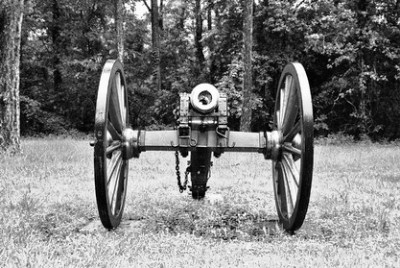

In the summer of 1863, competition between the Union and Confederacy for control of Chattanooga was getting fierce. Union Maj. Gen. William Rosecrans moved his nearly 70,000 men, known as the Army of the Cumberland, from Murfreesboro, TN to square off against Confederate Gen. Braxton Bragg’s Army of Tennessee. Originally positioned to defend the road to Chattanooga, Bragg’s 43,000 men were eventually forced into the city itself by Rosecrans’ forces. In late August, Bragg had to retreat again, this time to LaFayette, GA, 26 miles south of Chattanooga. With the addition of badly-needed reinforcements from Mississippi, East Tennessee, and Virginia, Bragg had 66,000 men when, on September 18, 1863, he tried to get between Union forces and Chattanooga by moving troops along the east bank of West Chickamauga Creek, a gambit which proved unsuccessful. Above is a photo of perhaps the largest of the countless monuments erected on the battlefield, many created by the states from which the soldiers came.

In the summer of 1863, competition between the Union and Confederacy for control of Chattanooga was getting fierce. Union Maj. Gen. William Rosecrans moved his nearly 70,000 men, known as the Army of the Cumberland, from Murfreesboro, TN to square off against Confederate Gen. Braxton Bragg’s Army of Tennessee. Originally positioned to defend the road to Chattanooga, Bragg’s 43,000 men were eventually forced into the city itself by Rosecrans’ forces. In late August, Bragg had to retreat again, this time to LaFayette, GA, 26 miles south of Chattanooga. With the addition of badly-needed reinforcements from Mississippi, East Tennessee, and Virginia, Bragg had 66,000 men when, on September 18, 1863, he tried to get between Union forces and Chattanooga by moving troops along the east bank of West Chickamauga Creek, a gambit which proved unsuccessful. Above is a photo of perhaps the largest of the countless monuments erected on the battlefield, many created by the states from which the soldiers came. A day later, on September 19, 1863, just after dawn, Union infantry engaged Confederate cavalry at nearby Jay’s Mill. Fighting spread amongst what was now well-over 120,000 troops, and the engagement soon covered four miles, the combat often hand-to-hand. At one point, a group of Confederate soldiers became stranded in a ravine near what is known as Viniard Field, and Union Col. John Wilder later wrote, “It seemed a pity to kill men so. They fell in heaps, and I had it in my heart to order the firing to cease, to end the awful sight.”

Eventually, Bragg began to drive the Federal army back and, on September 20, Rosecrans received a report that Union Brig. Gen. John Brannan’s division was out of position, putting the Federal line in jeopardy. This information was incorrect, but Union Brig. Gen. Thomas Wood moved his forces to fill the supposed gap in the line, thereby creating a real gap. Coincidentally, Confederate Lt. Gen. James Longstreet’s troops had just started to move toward the area now suddenly left vacant by Wood’s men. Thus, Longstreet’s men broke through the line and began to drive back Federal divisions, including Maj. Gen. Jefferson C. Davis’s.

With a hole in their line and Longstreet’s troops moving forward, the Union fell into retreat. Union Gen. George Thomas held the last position at Snodgrass Hill for a time and was thereafter known as the “Rock of Chickamauga.” He also commandeered the Snodgrass family cabin and turned it into a field hospital. But as darkness fell, Thomas and the other Union soldiers withdrew in defeat to Chattanooga. Over the course of two days the Battle of Chickamauga had resulted in 18,000 Confederate soldiers killed, wounded, or missing out of a total of 66,000 troops; Union casualties were 16,000 out of 58,000. The battle would stand as one of the deadliest of the war. Below is a photo of the site on which the Snodgrass cabin stood; the cabin itself is not original.

After the battle, Confederates pursued Union forces out of Chickamauga and took Missionary Ridge, Lookout Mountain, and the Chattanooga Valley, effectively barricading Rosecrans’ Army of the Cumberland inside the city. With no way to get supplies in or out, it looked bleak for Federal troops. However, Washington D.C. soon sent 20,000 reinforcements under the command of Maj. Gen. William Sherman and an additional 16,000 men under the command of Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker to aid the Army of the Cumberland. Thomas then replaced Rosecrans, and Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant took overall command. The first move was to open a supply line from Bridgeport, AL to get food to the stranded troops. Known as the “Cracker Line,” the primary foodstuff delivered to the hungry soldiers was hardtack crackers.

On November 23, 1863, Thomas went on the attack and drove Confederate troops from Orchard Knob. A day later heavy fog conspired to drive the Confederates from the seemingly well-positioned Lookout Mountain. With Bragg’s forces now concentrated on Missionary Ridge, Sherman’s troops moved toward the right flank and Hooker’s toward the left. Hooker was delayed and Sherman’s attack was fought back, so Thomas was ordered to move from his position at Orchard Knob, in the middle of the field, toward the base of Missionary Ridge. Thomas’s men not only marched to the ridge, but, without orders to do so, climbed it and took the position, driving Confederate forces back into Georgia. With the Confederate Army unable to return to the area, Chattanooga would now become the staging ground for Sherman’s march to Atlanta and onward to the sea.

On November 23, 1863, Thomas went on the attack and drove Confederate troops from Orchard Knob. A day later heavy fog conspired to drive the Confederates from the seemingly well-positioned Lookout Mountain. With Bragg’s forces now concentrated on Missionary Ridge, Sherman’s troops moved toward the right flank and Hooker’s toward the left. Hooker was delayed and Sherman’s attack was fought back, so Thomas was ordered to move from his position at Orchard Knob, in the middle of the field, toward the base of Missionary Ridge. Thomas’s men not only marched to the ridge, but, without orders to do so, climbed it and took the position, driving Confederate forces back into Georgia. With the Confederate Army unable to return to the area, Chattanooga would now become the staging ground for Sherman’s march to Atlanta and onward to the sea.

A couple things: First, the sheer number of men that were at Chickamauga is astounding. There are memorials to divisions from all over the country erected on the battle site. Even though Chattanooga was an important stronghold, it’s hard to understand why all these forces were amassed at Chickamauga Creek, on flat terrain, and at the same time. I guess it must’ve seemed like as good a place to fight it out as any. Also, if you’ve ever seen the lofty bluffs of Lookout Mountain, you’ve gotta wonder how the Confederate soldiers were driven off it. Even with a little fog it seems virtually impossible for the Confederate army to have believed that Union troops were scaling the bluffs. Plus, there was plenty of good mountain behind the Confederates, so the Union couldn’t have starved them off even if they’d wanted to. Add to that the faulty intelligence delivered to Rosecrans and there would seem to have been more than a few key errors on both sides. I suppose everyone could’ve used some walky-talkies. Thanks to the National Park Service for providing info for this post. See ya next time!

Friday, May 19, 2006

Checkin' In

Well, it's been awhile. I felt like getting some new shots up, so here ya go. I'm now in Knoxville and things are pretty insane. So far, I've scaled tall bluffs, explored an old coal mine, been shot at (I think it was meant as "fun"; some fun!), and nearly put my hand on a copperhead. I've got photos of most of these adventures (Yes, I actually thought about taking my camera out to photograph the people shooting at me, but decided to just get moving. I DID take a photo of the copperhead.) and I'll try to get them up soon. In the meantime, here's my life from March to April: A dead dashboard at the auto salvage in Savage, MN; a winter reprise at Westwood Hills Nature Center, St. Louis Park, MN; and, finally, Maggie Valley, North Carolina.

Stay tuned for much more from eastern Tennessee and beyond. For a preview, check my FLICKR site. I'm using a crummy digital camera for work and so the quality on the newer shots is a little lacking, but you'll get the, uh, picture.

Saturday, April 08, 2006

Gone Fishin'

Well, this week I'm moving to Knoxville, Tennessee, so City of Dust is going to go on a little hiatus. I'll try to post again once things have settled down a bit, but I can't say for sure when that will be. The good news is that Knoxville, besides being the hometown of my favorite author, Cormac McCarthy, and the setting for one of the most famous murder ballads of the 20th Century, is nestled along the Tennessee River, at the foot of the Appalachian Mountains, not far from Smoky Mountain National Park, and just across the border from Asheville, North Carolina. In short, my camera is giddy with anticipation and, hopefully, posts will return to the original City of Dust format. That is, photographs and forgotten tales from the crumbling, kudzu-shrouded backroads of the American South; I'm just moving one state higher up. If you want to whet your appetite for the South, check out Searching for the Wrong-Eyed Jesus, the trailer for which can be seen here.

In the meantime, hell, there's an entire novel on this site, and it begins here. Further, over 300 years of history from the Central Savannah River Area of Georgia/South Carolina commences here. There's also a bunch of fictional oddities and lots of desert. I could use a break--and I bet you could too.

During my absence, City of Dust will be presided over by the bloodthirsty tabby pictured above. His name is McCarthy and, while he didn't write Blood Meridian, I'm sure he's capable of equally impressive feats of violence. Just because he's declawed and neutered doesn't mean he's not dangerous. He will forward any comments left here directly to me. And, if anybody has anything to say about Knoxville (or lives in Knoxville), please drop me a line--I'd love to hear whatever you have to say.

See ya in awhile.

J.

Monday, April 03, 2006

A Loss for Words Pts. 33, 34, and Last

(CONTINUED) Thirty-Three

We drove around Tucson for awhile because there was nothing else to do. Again we discussed going to the police, but if that had seemed like a bad idea in Santa Fe, it felt like signing Jimmy’s death certificate now. Of course, I would have been unable to go to the police anyway. We stopped and got some fast food and ate a little of it. Then, at some point, we found ourselves on I-19 headed south. Within a couple of miles downtown Tucson gave way to ramshackle, weather beaten homes sitting on plots of barren yellow dirt, with all manner of rusted cars, desperate animals, and stricken children out front. From the highway we could see even more forlorn shacks in the distance, walls and roofs of wood or metal seemingly thrown up without thought to safety or permanence. A few miles farther and even these crude shelters thinned-out, giving the impression that neighborhoods did not exist in this place, but rather each family existed on their own island of dust, consumed by their individual troubles and difficulties, afraid that soon even the little they had would also be gone, consumed by the relentless desert.

A gust of wind blew yellow dust high into the cloudless sky and a sign on the highway marked an exit for Vallejo Dr. There was nothing around that wasn’t abandoned or destroyed, no gas stations or restaurants, just a forgotten road disappearing somewhere out into the Sonoran Desert. We were early, so I pulled the car off to the shoulder and got out. There was no one to be seen in any direction. I opened up the trunk, took the shotguns out of their cases, and laid them in the back seat. Then I got back into the car and took the 9 mm out of the holster on my shoulder. I held it in my hand.

“Are you ready?” I asked.

“For what?” Julie replied. “We don’t have a plan. Are we just going to offer them the money and hope they take it?”

She didn’t sound hysterical or angry; she sounded like someone that had simply considered the situation and found the odds greatly against her. She was right.

I put the gun on my lap. “We’ll do whatever we need to do to get your brother back safely. But we won’t know what that is until we meet these people.”

“I think it’s a trap.”

I looked around at the glittering desert that ran out in every direction. Some distance back traffic whistled up and down I-19, the sun flashing sickeningly off the aluminum semi-trailers. In front of us was nothing that I could see. “Do you have another idea?”

Julie turned to me and her face crinkled, as if she was going to start crying. She shook her head. I leaned over and kissed her. “We’ll be alright; all three of us.” She nodded like she didn’t believe me. I told her to unzip her windbreaker and get the .38 out of the holster. She did and I took the gun from her. It was loaded and the safety was off. I gave it back to her. “Fuck it,” I said, taking in that vast emptiness one last time. “Out here, if you think you need to shoot, just shoot.” It was 2:50 PM.

I fired up the Jag and we began driving slowly down Vallejo. I was watching for anyone that might be waiting for us, but nothing moved. Eventually the pavement ended and the road became dirt. About a mile off we could see a structure in front of us; an old house, sitting behind the remains of a wooden fence. As we got closer I could see that it was two stories high and made of brick that had been painted white. There were two windows above a rotted patio on the front, but they’d been boarded up. On the first floor there were no windows, but two doors. There were some rusted cars in the yard, but no vegetation. A few small outbuildings were scattered nearby and I wondered if there was anyone in them, their rifle sights trained on us. I narrowed my eyes against the glare, but I saw nothing in the yard, just the shimmering of the sun. As I pulled the Jag up I noticed the beige Land Rover parked alongside the house. It was the only vehicle visible.

I turned off the Jag and listened. Nothing. Not any sound at all. I reached into the back seat and grabbed the sack of cash and some ammo clips. Then I leaned over and put the gun in the back of my waistband. “You wait here,” I told Julie. She gripped the .38 more tightly and that pleased me. “If you hear any shots from inside, just drive out of here. Start the car and go. If anyone approaches you, shoot them.” She didn’t say anything. “Do you understand?” She looked toward the house and then back at me; she nodded. “Good. Now I’m going to go get your brother.”

I stepped out of the car and sank to my ankles in sand. I was almost to the front porch when a shot slammed into the front door of the house from my left side. For a moment I wondered if it was a warning shot, but a second shot came at me from a different direction and I dropped to the ground. I yelled for Julie to get the hell out, but didn’t hear the car start. I pulled the gun out of my waistband, let go of the sack, and began crawling through the sand for the house. I was at the front step when I saw movement behind the shell of an old car off to my left. I squeezed the gun in my right hand and waited. I could hear my heartbeat slamming in my ears and then everything seemed to slow down as, out of the corner of my eye, I saw a man begin to rise from behind the car. In one movement I pulled myself up to a squat, leveled the gun, and fired. I heard a return shot as I dropped back to the ground but I could not tell where my bullet went. I glanced back toward the car; no movement. My ears were ringing and I could smell the cordite. I quickly climbed onto the patio and looked toward the Jag. I couldn’t see anyone in it. I hoped that Julie had ducked down below the window to avoid the gunfire, but I couldn’t be sure. Just then another shot rang out from the right side of the house. It ricocheted off a brick near my head. I crouched down and tried one door and then the other. They were both locked. I crawled over to the left side of the house and raised myself up slightly, just enough to peer over the short brick wall that enclosed the porch. Nothing. I dropped back down, waited a moment, then raised myself up again. Still nothing. I raised myself one more time, a little higher. Nothing. I leaped over the side of the porch and pressed myself against the side of the house. Then I saw the man behind the car lying in the dust. He wasn’t moving. I looked one more time toward the Jag, but I still didn’t see Julie--or anyone else. I hoped the other shooter--and anyone else--would come after me.

Slowly I crept along the side of the house and at the back I saw a ramshackle set of wooden steps leading to the second story. I stepped around the corner and was almost to the stairs when a shot hit the railing, splintering the desiccated wood. I dropped into the sand again and tried to locate the shooter. There were two outbuildings on that side and I was pretty sure the shot had come from one of them, but I didn’t know which. I was pinned down, so I fired at the building on the left. I waited a moment but my shot was not returned. Then I fired at the building on the right and a split-second later a bullet whizzed a couple feet over my head. I unloaded the rest of my clip into the building and, as I was jamming a new clip into the gun, I saw the man run out from behind the building toward the front of the house. I shot three times in quick succession and he fell just a step before the house would’ve blocked my bead on him. Then I stood and picked my way quickly and carefully up the steps.

At the top of the stairs was a door and I eased it open then waited a moment before entering. Inside was a small entry room strewn with old newspapers, rotted clothes, and garbage. Dirt was two inches thick on the floor. Another door opened out of the little room. I opened it gently with my foot and stepped quickly back from the doorway but a voice from the other side said, “Come in.” I glanced around the jamb and saw a much larger room. On the far end was a small platform, perhaps a foot high, and Jimmy and a man were on top of it. Jimmy was seated, his arms and legs tied to the chair, and he was gagged and blindfolded. The man had a gun pressed to Jimmy’s temple. “You might as well come in,” he said. “Because, if you don’t, in a few seconds you’ll hear a shot and then all of this will have been for nothing.” I began to step into the doorway, leading with the gun, but the man said, “No, no, no, not like that. Put your hands up.” I hesitated, but the man drew the trigger back slightly on his own gun and Jimmy shivered, so I raised my hands over my head, hooking my index finger through the trigger guard of the gun, letting it hang free. I stepped into the dark, dusty room and got a good look at the man, who had long, greasy black hair and was wearing shorts and a tank top. He smiled as I came toward him and I knew then that he was no big-time dealer but a common street thug. He was undoubtedly working for someone else; I just hoped they wouldn’t show up. “You must’ve killed those guys, huh?” The guy laughed as I came closer. “I guess you’re pretty tough. The boss ain’t gonna like that. I’m not lookin’ forward to explainin’ it to him.” I was about ten feet away from Jimmy and could see his chest heaving. His clothes were spattered with blood and his face and arms were bruised. He’d been beaten up, but I couldn’t tell how badly. His right hand was tied tightly to the chair so I couldn’t see where his finger had been cut off.

“Where’s the money?” the man asked.

“It’s in the front yard,” I said.

He looked at me strangely. “The front yard?”

“I needed to have my hands free.”

He smiled again. “Of course. Is it all there?”

I looked around the empty room. There was nowhere to hide, no easy escape. “As much as we could get,” I said.

His smile quickly became a frown. “Where’s the girl?”

“In the car.”

Now he smiled broadly and it told me a lot about him, more than I would’ve liked to have known. “Ah, that’s good. Joey--that’s the guy who was tailing you--I guess you just killed him--Joey said the kid’s sister’s a looker.” He tousled Jimmy’s hair with his free hand. “I guess it runs in the family. Anyway, we had some plans for you guys. We sure as hell did.” He looked casually around the room and I noticed a bag and a pile of rope at his feet. Then he turned back to me and laughed. “But now it’s just me with the plans.” Suddenly he kicked Jimmy’s chair hard and the kid went head over heels off the platform. I tried to aim my gun, but it was too late. A bullet hit me in the left side and the shot I got off was so high it probably went through the roof. I reflexively dropped the 9 mm, put my hand to the wound, and fell to the ground. It hurt more than I could believe. I’d heard that sometimes there was numbness or a dulling of sensation, but I was not so lucky. Blood ran through my fingers, sticky and warm. I thought of Anne, shot in the stomach just like me, and wondered if she’d been in as much pain as I was in. It hadn’t seemed that she’d suffered, but maybe she’d just been unable to communicate what she’d felt. The thought was unendurable.

I heard footsteps approaching me from the platform, dull thuds against the old wooden floorboards. I heard the man kick the 9 mm away and when I looked up I saw him standing over me, the gun pointed at my face. He laughed. “Now you’re all going to die, but I’ll just get you out of the way first.” He looked around the room once again and said, “I don’t know where the girl went, but I bet I can find her. Personally, I wouldn’t have brought her out here for this. But the three of us will make a night of it now.” He drew the hammer back on the gun. “I just wanted you to know that before you died.” I closed my eyes. For a brief moment I thought of Anne and wondered if I’d see her. But then I thought of what might lay ahead for Julie and Jimmy and what my role had been and I felt something that there are simply no words for. If I couldn’t stop what was going to happen, if this was the place I’d brought Julie to, then I wanted this man to kill me. Seconds passed and nothing happened. Suddenly everything seemed strangely still and quiet so I opened my eyes and saw that the man had his hands up and a funny expression on his face. I could see that Julie was standing behind him and, though I couldn’t see much of her, I noticed that she wasn’t wearing shoes. I knew immediately that she had the .38 pressed to the back of the man’s head. The man tried to laugh. “Well, ha ha, let’s just take it easy now. I only wanted to scare…” But before he could finish his sentence there was a crack that echoed loudly through the big empty room. The man dropped to the floor and a fine mist fell across my face. Blood and brain matter; I could taste it on my lips. Julie just stood there, holding the gun in front of her. Her clothes were spattered with gore. She didn’t look at me and she didn’t look at the man she’d just killed. She didn’t even look at her brother. She just stared straight ahead, as if no one else was there. As if nothing had happened. I tried to say something, but a bolt of pain flashed through my side and I just groaned. Julie slowly lowered the gun and looked at me. I pointed to Jimmy, still tied to the chair, now sideways on the floor, struggling uselessly to free himself. Julie ran to him and it seemed to take her a long time to get the ropes off. I heard her cry out and I assumed she’d just seen his hand with the pinky finger hacked-off. A few seconds later she and Jimmy were by my side. Jimmy looked bad, but it seemed like he could get around. I, on the other hand, was in somewhat worse shape.

“My God,” said Julie, kneeling beside me, her hands already bloody. “We need to get a doctor.”

I shook my head. “Just get me out of here,” I gasped. “Let’s go for Mexico.”

Julie touched my side and the pain was excruciating. “You can’t get across the border.”

I managed to sit up. “Let’s worry about that when we get there.” I took a deep breath and saw stars. “We need to leave now before anyone else shows up.”

“He’s right,” Jimmy said. “Those guys were just hired for the job.”

“You mean there’s someone else?” Julie asked.

Jimmy picked the 9 mm up off the floor and then told his sister to take my left arm. But he didn’t answer the question.

They got me to my feet and we started for the door. Neither of them was strong enough to support my weight, so I worked to keep myself upright by favoring my right side. We stopped at the top of the steps and Julie got her shoes and put them back on. “Can you drive a stick?” I asked her. She nodded and then we started down the rickety staircase, slowly, fighting for balance. It seemed to take an eternity to descend one story. After that, it was easier to get through the yard to the car; the pain was lessening, but I was beginning to feel weak and woozy. Julie opened the back door for me, but I told her I was going to ride up front. “There’s something I have to tell you,” I said. “And I have to do it now.” Jimmy helped me into the passenger seat and when I sat down it felt like a hot poker had pierced my side. I struggled for breath. Julie asked me if I was okay and I nodded. I told Jimmy to grab the bag of cash off the lawn and then he got in the back seat, the shotguns across his lap. Julie came around the driver’s side. The keys were still in the ignition and she turned the motor on, backed around, and headed toward the interstate.

Thirty-Four

We could just see I-19 up ahead, the cars like cast iron toys, when I told Julie to pull over. There was no one else on Vallejo Dr, which was probably not unusual. Off the road was an old weather-beaten shack. I gave Jimmy the 9 mm and told him to get the .50 caliber out of my bag. The guns were a liability now and we had to get rid of them. If we found ourselves in a situation where we needed to start shooting, there’d be no hope for us anyhow. Julie gave her brother the .38 Special and then I told him to take all the guns and the shotgun bags to the shack and see if there was any place inside where he could hide them. He got out of the car and limped to the shack; at the house I hadn’t noticed that his leg was injured. He seemed to be having trouble holding the guns, probably because of his hand, which I’d forgotten about, but in a few moments he was back.

“There was some corrugated metal in there,” he said. “I put them under that.”

“Good enough,” I replied. Then I told him to put the sack of cash in the trunk; we couldn’t afford to leave that.