Tonlẽ Sap is the largest lake in Southeast Asia, fed by or, depending on the season, feeding the mighty Mekong River. The water level fluctuates from a depth of about 10 m in the wet season to 2 m in the dry and the lake nourishes a huge chunk of the region, providing a livelihood to thousands-upon-thousands. In an effort to lure visitors and their money away from Angkor Wat for awhile, the Cambodian government promotes trips to Tonlẽ Sap, particularly to visit the floating villages. These floating villages are just what the name implies, complete with schools, stores and churches. The tours are described as relaxing boat rides through a unique and picturesque waterscape. But when traveling it is often the height of naivety to expect all to be as it’s portrayed. And therein lays the fun.

After a sweltering day-and-a-half visiting the mind-blowing Angkor Wat complex, my friend and I decided to visit Tonlẽ Sap and Chong Kneas, the closest of all the floating villages to Siem Reap. We asked our friendly and reliable tuk-tuk driver (#2205) if he could take us to the lake and he assured us this was no problem. Soon we were rattling through dense traffic and endless road construction. Several times we had to get out and walk while the driver took the tuk-tuk off-road for brief stretches to get around obstacles. I inhaled more dust than I had over the previous 36 hours, which is really saying something. I dearly regretted not buying a cheap mask at the pharmacy as many people, locals and visitors alike, do. My throat was going to be sore for days.

Following a quick stop at the tuk-tuk driver’s house so he could drop off some fruit for his family, we were out of Siem Reap and into…something very different. Poverty on a large scale is always disarming, and the shacks and shanties on the road to the lake were the first indication that economics might be about to intrude on our scenic boat tour. We got to the boat launch about 4 pm and bought a ticket for a “government” boat (private boats are apparently available, but it’s not clear how to get them) with an extra “sunset” fee (i.e., a charge for staying on the water long enough to watch the sun go down). Thus began a very strange journey.

The entire floating village moves with the seasonal change in water level and, as the water was still quite low in the early spring, Chong Kneas was about as far out in the lake as it ever gets. Consequently, we had a long trip to the village, past all manner of boats, most patched up 10,000 times over with material of every description. Along the narrow channel leading into the lake dilapidated houseboats were moored everywhere possible and occasionally someone would be swimming in the filthy water. Had I dove in for a quick dip my immune system would’ve thrown up its hands in defeat and called it a day. Everything was totally fascinating and exotic and disturbing, as only 3rd world poverty can be. Immediately our gregarious guide started talking about how poor the people of Chong Kneas were and how they needed money for many things. I sensed a pitch coming on.

The village itself was an incredible array of dozens of ramshackle floating structures broken into Vietnamese, Muslim, and Cambodian sections. It looked more like a floating ghetto, perhaps, but it was difficult to gauge how comfortable the people were in their situation.

During our trip we interacted with very few residents and no one seemed to pay us any mind as our boat went along. We passed a pig in a floating pen and a Catholic church. Then, without warning, we pulled up at a market, disembarked and were shown school supplies. It was suggested that for $20.00 we could buy a package of books and some pencils for the kids at school. Outside was a mean monkey on a chain that lunged at my friend when he tried to take a photo. Earlier, I'd had no such trouble. The guide warned us to back away from the monkey. So, what the hell can you do? We handed over $20.00 and our guide put the books and pencils into a bag. We got back into our boat just as a French family in an identical boat was docking.

We sailed right over to the school where the kids were just getting out of class and into their own boats to go home. Inside we were introduced to the teacher and got our picture taken giving him the books and the pencils. Similar pictures of previous tourists lined the walls. We were told we could take photographs of some of the children. I asked one girl if she wanted her picture taken and she laughed and shook her head. I left her alone.

O

ur guide then told us that the teacher could use some money to buy supplies for the classroom and extra food for the kids. I gave $10.00 to the teacher, who struck me as looking a little sheepish about the whole thing. On the way out I saw the French family getting out of their boat with a bag of notebooks and pencils.

Next we headed through the village and boarded a restaurant boat complete with an on-board crocodile farm and some voracious fish in a wooden tank. We decided to pass on the dinner. After a tour of the boat and a little biology/geography lesson, we were sold a can of soda and then sat down at a table with a well-spoken and very effeminate fellow, a self-proclaimed ladyboy, who told us he loved Pelẽ, Brazilian football and WWF Smackdown. He and our guide seemed to be friends, although our guide went out of his way to appear annoyed with him.

After awhile we climbed up some stairs and checked out the view from the top of the boat. The floating village was spread out before us, the sun slowly sinking into Tonlẽ Sap. We decided to head out early in order to get some photos from the water before the sun set completely. There was a slight delay as we helped out a boat with a dead battery. The family in the boat was clearly unhappy with the way their trip had been going. They were making no bones about it. It was hard to have much sympathy for them.

We sailed out past people fishing and washing from the porches of their houseboats in the muddy-brown water. There were a few bonfires burning off on the shore. As we made our way back through the channel our guide said the Cambodian government had plans to make the entire area a world-class shipping port, essentially eliminating all that we saw around us. Lord knows how this would work. For one thing, they’d have to do considerable work to stabilize and dredge the lake as its area swings wildly from 3,000 to 10,000 sq. km and it can be very shallow, depending on the season and rainfall. Yet there was evidence of construction on the banks nearby.

By the time we returned to shore it was pitch dark. Our guide mentioned that he needed money for school and was very disappointed when I said I didn’t have much left. I scrounged up $5 for him and $2 for the driver. I considered telling the guide he should’ve pitched less for everyone else if he wanted something for himself. How much of this was a scam I have no idea. Other tours are advertised, but they seem pretty cheesy and are mostly billed as “dinner tours.” Maybe the schoolteachers and the boat guides are in cahoots and splitting the proceeds. Maybe the government is taking the money and using it for its own purposes. Or--who knows?--maybe it’s legit. But it’s hard to imagine there’s not some skimming somewhere. All told, this was probably a $50.00 ride by the time it was over.

In reality, the village is spectacular and unusual, even if disconcerting. And I was happy that I had a look at Chong Kneas, despite the lingering feeling of being ripped-off. But I thought back to the previous day in Angkor Wat, when a young boy tried to sell me a bootleg guide to the temples. At first he said the book was one dollar. “One dollar?” I asked. I could afford that. “No, three dollars,” he said. I hesitated. “Five dollars,” he continued. This was a very unusual business tactic. “What happened to one dollar?” I asked. “It can’t be less than five,” he replied. He was probably working under the instructions of whoever supplied the books. “I can’t afford five dollars,” I said. “I don’t have any money.” This was technically true as I was traveling my way deeper into debt with every step, but the kid was having none of it. His eyes hardened and he glared up at me. “You are from America. You have come to Cambodia. You have money. I will wait until you are ready to leave the temple and then you will buy the book.” I laughed but he did not. So I walked around for awhile and on my way out, sure enough, there was the kid with his book. I handed him the $5 and he grumbled his thanks and walked off. In travel, as in life, sometimes you have to let yourself be ripped-off a little. It’s only fair.

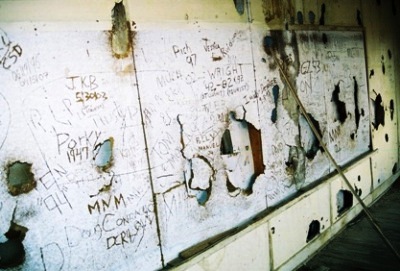

Thus, the selected inmates, in cooperation with their fellow prisoners, made sure that order was maintained and no one jeopardized their good thing. However, by the late 1970’s, the New Mexican correctional system was in disarray. The chain of command among prison officials was weak and confusing and oversight of regulations lax. Around this time prisoner-led programs ended and a new policy was implemented, one whereby prisoners were routinely turned against other prisoners and coercion was used to obtain information and overall compliance. Divide and conquer became the guiding objective. (Accompanying photo shows cell graffiti. Regulations forbidding graffiti were relaxed just before the penitentiary closed.)

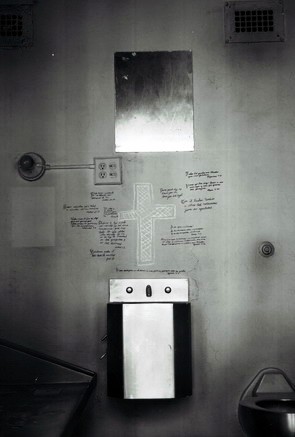

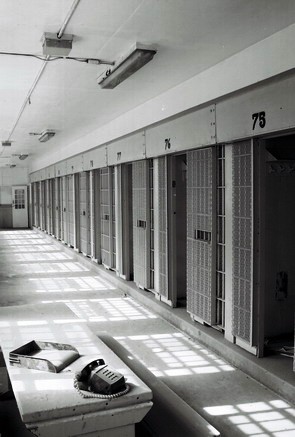

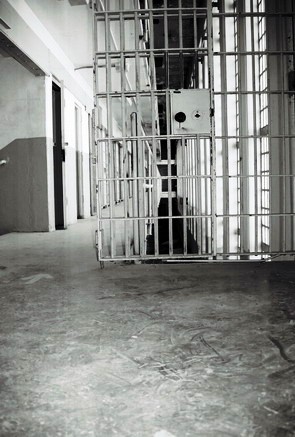

Thus, the selected inmates, in cooperation with their fellow prisoners, made sure that order was maintained and no one jeopardized their good thing. However, by the late 1970’s, the New Mexican correctional system was in disarray. The chain of command among prison officials was weak and confusing and oversight of regulations lax. Around this time prisoner-led programs ended and a new policy was implemented, one whereby prisoners were routinely turned against other prisoners and coercion was used to obtain information and overall compliance. Divide and conquer became the guiding objective. (Accompanying photo shows cell graffiti. Regulations forbidding graffiti were relaxed just before the penitentiary closed.) This included prisoners who had given evidence against their fellow inmates. Moreover, when built in 1956, the prison was designed to contain 800 men. By 1980 more than 1100 prisoners lived together in close quarters. A renovation of a cellblock at the time saw some of the most dangerous criminals moved from a high-security area to more dormitory-like arrangements. This overcrowding and mixing of New Mexico’s most violent, notorious, disturbed and vulnerable criminals in one facility was more fuel to be tossed on what was already becoming a dangerous powder keg. (Accompanying photo is of a death row cell. Photo below is of a meeting table beside death row.)

This included prisoners who had given evidence against their fellow inmates. Moreover, when built in 1956, the prison was designed to contain 800 men. By 1980 more than 1100 prisoners lived together in close quarters. A renovation of a cellblock at the time saw some of the most dangerous criminals moved from a high-security area to more dormitory-like arrangements. This overcrowding and mixing of New Mexico’s most violent, notorious, disturbed and vulnerable criminals in one facility was more fuel to be tossed on what was already becoming a dangerous powder keg. (Accompanying photo is of a death row cell. Photo below is of a meeting table beside death row.)

While on their rounds during the early morning of February 2, two guards came upon a couple of prisoners in a dormitory that were drunk on alcohol they’d made with fermented fruit. The intoxicated inmates attacked and overcame the guards and, as the guards had failed to follow procedure, leaving the cell block doors they had just come through open, the prisoners quickly made their way to the prison’s control center, where they flipped switches unlocking most of the penitentiary. Once free, hundreds of inmates fanned throughout the prison, taking fourteen guards and one medical technician hostage. While things were about to get much, much worse, some inmates were already fighting the tide and three guards were given safe hiding places by sympathetic prisoners. Meanwhile, anything that could be used as a weapon was procured and made into one, and the hospital was raided for its drug supply. Even glue was sought out and huffed. (Accompanying photo and photo below are pretty self-explanatory.)

While on their rounds during the early morning of February 2, two guards came upon a couple of prisoners in a dormitory that were drunk on alcohol they’d made with fermented fruit. The intoxicated inmates attacked and overcame the guards and, as the guards had failed to follow procedure, leaving the cell block doors they had just come through open, the prisoners quickly made their way to the prison’s control center, where they flipped switches unlocking most of the penitentiary. Once free, hundreds of inmates fanned throughout the prison, taking fourteen guards and one medical technician hostage. While things were about to get much, much worse, some inmates were already fighting the tide and three guards were given safe hiding places by sympathetic prisoners. Meanwhile, anything that could be used as a weapon was procured and made into one, and the hospital was raided for its drug supply. Even glue was sought out and huffed. (Accompanying photo and photo below are pretty self-explanatory.)

Other prisoners tried to protect certain of their fellow inmates and lost their lives because of it. Still others worked to release the guards. Such was the disarray and lack of leadership that prisoners could release hostages while their fellow inmates made demands intended to be met before these very same hostages would be released. (Accompanying photo is from Cell Block 4, where prisoners in protective custody were housed. The slender white marks on the floor in the foreground were caused by hatchets used to dismember inmates.)

Other prisoners tried to protect certain of their fellow inmates and lost their lives because of it. Still others worked to release the guards. Such was the disarray and lack of leadership that prisoners could release hostages while their fellow inmates made demands intended to be met before these very same hostages would be released. (Accompanying photo is from Cell Block 4, where prisoners in protective custody were housed. The slender white marks on the floor in the foreground were caused by hatchets used to dismember inmates.) Those entering the prison found true horror: bodies had been put in ovens in the kitchen, limbs were scattered on the ground, one corpse had no head, another was hanging from the ceiling with the word “RAT” cut into its chest, yet another had a metal bar shoved in one ear and out the other. The bodies of two inmates were never found and were presumed entirely incinerated. All told, the 36-hour nightmare left at least 33 inmates dead and nine seriously injured. One guard was in serious condition--some guards were badly beaten and sodomized--and the New Mexican Corrections Department had been brought to its knees. (Accompanying photo is from Cell Block 4. The dark stain on the floor marks where a body was burned.)

Those entering the prison found true horror: bodies had been put in ovens in the kitchen, limbs were scattered on the ground, one corpse had no head, another was hanging from the ceiling with the word “RAT” cut into its chest, yet another had a metal bar shoved in one ear and out the other. The bodies of two inmates were never found and were presumed entirely incinerated. All told, the 36-hour nightmare left at least 33 inmates dead and nine seriously injured. One guard was in serious condition--some guards were badly beaten and sodomized--and the New Mexican Corrections Department had been brought to its knees. (Accompanying photo is from Cell Block 4. The dark stain on the floor marks where a body was burned.)

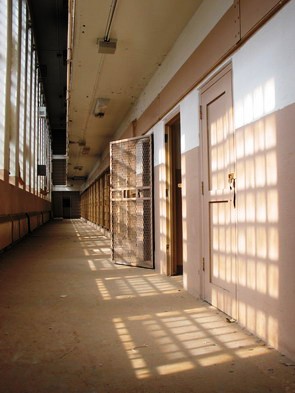

But, beyond that, and in overpowering opposition to those inmates, possibly the vast majority, who did not participate or even risked and lost their lives to reduce the violence, something unspeakably wicked was at work over those 36 hours. James Weston, the Chief Medical Examiner at the time, was quoted as saying, "Virtually every one of the bodies had overkill, which is to say that there was more than mob hysteria. There was rage." That much seems abundantly clear, but the prison psychologist, Dr. Marc Orner, made a much more telling statement when he said, "None of us really understands what happened in there. The depth of the violence is incomprehensible to me as a human being and as a psychologist. It is as if all the aggression a human being can have was savagely unleashed. We just can't understand why they did this to each other." (Accompanying photo shows a few rays of sunlight.)

But, beyond that, and in overpowering opposition to those inmates, possibly the vast majority, who did not participate or even risked and lost their lives to reduce the violence, something unspeakably wicked was at work over those 36 hours. James Weston, the Chief Medical Examiner at the time, was quoted as saying, "Virtually every one of the bodies had overkill, which is to say that there was more than mob hysteria. There was rage." That much seems abundantly clear, but the prison psychologist, Dr. Marc Orner, made a much more telling statement when he said, "None of us really understands what happened in there. The depth of the violence is incomprehensible to me as a human being and as a psychologist. It is as if all the aggression a human being can have was savagely unleashed. We just can't understand why they did this to each other." (Accompanying photo shows a few rays of sunlight.)

We pulled into the driveway of a small house in a neighborhood that looked like it had been built sometime in the 1950’s. Inside debris was strewn here and there, the detritus of a lifetime. A rhinestone rodeo shirt was draped over a chair, a box of old Christmas ornaments sat in the corner. A few things had price tags.

We pulled into the driveway of a small house in a neighborhood that looked like it had been built sometime in the 1950’s. Inside debris was strewn here and there, the detritus of a lifetime. A rhinestone rodeo shirt was draped over a chair, a box of old Christmas ornaments sat in the corner. A few things had price tags.