It was almost 10 years that I worked for the county, up until I couldn’t really take it anymore. For all that time I cleaned-out houses that were going to auction after their owners had died without leaving a living relative or specifying a beneficiary. Sometimes I’d show up pretty much right as the medical examiner was loading the body into the ambulance. Other times it took quite awhile to comb through the deceased’s past and determine if they were, for our purposes, at least, alone in this world. Some people talk about immortality as something to be desired but, from what I’ve seen, outliving (or, perhaps, living long enough to alienate) every one of your friends and family is a fate a far sight worse than death.

It was almost 10 years that I worked for the county, up until I couldn’t really take it anymore. For all that time I cleaned-out houses that were going to auction after their owners had died without leaving a living relative or specifying a beneficiary. Sometimes I’d show up pretty much right as the medical examiner was loading the body into the ambulance. Other times it took quite awhile to comb through the deceased’s past and determine if they were, for our purposes, at least, alone in this world. Some people talk about immortality as something to be desired but, from what I’ve seen, outliving (or, perhaps, living long enough to alienate) every one of your friends and family is a fate a far sight worse than death. You might think that I’d have come across some pretty cool things over the years and, in fact, I was explicitly barred from taking anything for myself from any of the homes I worked. On one occasion, in amongst a stack of worthless albums by the Ray Coniff Singers and Bing Crosby, I found a Blind Lemon Jefferson 78 rpm record. “Bad Luck Blues” on one side and “Broke and Hungry” on the other. I slid the record into the duffel that held my lunch even though I don’t have the equipment to play it.

Another time I found a water-stained photo of Marilyn Monroe signed, “To Petey, Love Always, MM.” I’ve tried to compare the writing against other examples I’ve found on the internet and can’t be sure but it might be authentic. Really, though, most of what was in these houses, the vast, vast majority, was of no use to anyone. Old photo albums, paperbacks, clothes, trinkets of every sort and description; things that mattered only to the decedent. Most of this gets put in black plastic bags and taken to the landfill. Even the Goodwill didn’t want it from us. Furniture that is in nice shape, electronic equipment, appliances, and things of some obvious value are shipped to a warehouse and auctioned off four times a year. You might not think that in a city of this size enough people shuffle off this mortal coil entirely without heir to warrant such an operation. In fact, I was part of a twelve-person team and we struggled not to run a backlog.

Another time I found a water-stained photo of Marilyn Monroe signed, “To Petey, Love Always, MM.” I’ve tried to compare the writing against other examples I’ve found on the internet and can’t be sure but it might be authentic. Really, though, most of what was in these houses, the vast, vast majority, was of no use to anyone. Old photo albums, paperbacks, clothes, trinkets of every sort and description; things that mattered only to the decedent. Most of this gets put in black plastic bags and taken to the landfill. Even the Goodwill didn’t want it from us. Furniture that is in nice shape, electronic equipment, appliances, and things of some obvious value are shipped to a warehouse and auctioned off four times a year. You might not think that in a city of this size enough people shuffle off this mortal coil entirely without heir to warrant such an operation. In fact, I was part of a twelve-person team and we struggled not to run a backlog.Of course, the first rule of the job is not to get involved. Don’t read the personal correspondence. Don’t try to put meaning to the faces in the pictures. And don’t try to reconstruct the last days or years of the deceased. Remain detached. Keep filling the black plastic bags. It’s hard.

I think most people expect that death will be a passageway from a life well-lived to something even better. Surrounded by our family and friends there will be anxiety and tears, to be sure, but also the warmth given off by a lifetime of memories and the knowledge that, in a very real way, our life continues in those that come after us. Perhaps it is like that for some. But the evidence I’ve seen would indicate that the end of life can also be a long slide into oblivion, the weight of regret hanging heavy as dreams go unfulfilled or collapse in on themselves entirely. When the mind finally can’t cope I guess madness sets in. I often found it something to consider as I tried to not get involved.

I think most people expect that death will be a passageway from a life well-lived to something even better. Surrounded by our family and friends there will be anxiety and tears, to be sure, but also the warmth given off by a lifetime of memories and the knowledge that, in a very real way, our life continues in those that come after us. Perhaps it is like that for some. But the evidence I’ve seen would indicate that the end of life can also be a long slide into oblivion, the weight of regret hanging heavy as dreams go unfulfilled or collapse in on themselves entirely. When the mind finally can’t cope I guess madness sets in. I often found it something to consider as I tried to not get involved.

A good number of the homes I went into were what you might call “garbage houses,” the former occupants having hoarded mountains of worthless material items against a yawning spiritual and emotional void. Old newspapers. Cereal boxes. Children’s toys (despite there apparently having been no children around lately). Bits of yarn. Anything that might be of some use in a future that would never arrive. When it got real bad we had to call in a HAZMAT team. My own father lived in a house somewhat like this. As a boy I recall a mix of anticipation and revulsion as I dug around in drawers looking for interesting artifacts or stalked around piles of old magazines that had begun to disintegrate in backed-up sewage.

The lights in the basement didn’t work and I had to use a flashlight to make my way over the cracked concrete floor, occasionally scaring up the ragged old black cat my dad kept, while holding my shirt over my mouth and nose, afraid of catching some type of disease. Even the garage was piled high with junk, some of which--strange medallions, old coins, car parts--I found truly fascinating. But, in the end, my wariness always won out and I was careful to keep some distance from both my father and his house, sensing, however obliquely, that what was reflected, each in the other, could do me harm. When my father died a few years later there was no clean-up or estate auction. Instead, the city bulldozed his house and everything in it to the ground and carted the wreckage off to the dump. I went by twice afterward; once to see the flattened house and again to see the newly vacant lot. To this day I think that this is really the right and proper way to deal with such homes. Thus, I suppose, I do believe it would be better if jobs such as mine didn’t exist.

The lights in the basement didn’t work and I had to use a flashlight to make my way over the cracked concrete floor, occasionally scaring up the ragged old black cat my dad kept, while holding my shirt over my mouth and nose, afraid of catching some type of disease. Even the garage was piled high with junk, some of which--strange medallions, old coins, car parts--I found truly fascinating. But, in the end, my wariness always won out and I was careful to keep some distance from both my father and his house, sensing, however obliquely, that what was reflected, each in the other, could do me harm. When my father died a few years later there was no clean-up or estate auction. Instead, the city bulldozed his house and everything in it to the ground and carted the wreckage off to the dump. I went by twice afterward; once to see the flattened house and again to see the newly vacant lot. To this day I think that this is really the right and proper way to deal with such homes. Thus, I suppose, I do believe it would be better if jobs such as mine didn’t exist. Or, I should say, jobs such as mine used to be. I’d like to relate that one day some dramatic realization hit me in some filthy home whose tainted atmosphere suddenly struck me deeply with a dire message. That would be interesting. But, I think, it was more a process of attrition, each “case,” wearing me down a bit more until all I saw was the utter futility and grinding isolation of lives that came to an end surrounded by useless bits of paper and plastic and not much else. We can’t always choose our fate but I’ve seen a lot of what happens when life is simply left to follow its own slow, sad course. Someone had better be at the wheel at all times. What I saw were lives and deaths empty of action or meaning. Finally, I couldn’t stomach the waste. I just had to turn away and find something better to do with my time.

Or, I should say, jobs such as mine used to be. I’d like to relate that one day some dramatic realization hit me in some filthy home whose tainted atmosphere suddenly struck me deeply with a dire message. That would be interesting. But, I think, it was more a process of attrition, each “case,” wearing me down a bit more until all I saw was the utter futility and grinding isolation of lives that came to an end surrounded by useless bits of paper and plastic and not much else. We can’t always choose our fate but I’ve seen a lot of what happens when life is simply left to follow its own slow, sad course. Someone had better be at the wheel at all times. What I saw were lives and deaths empty of action or meaning. Finally, I couldn’t stomach the waste. I just had to turn away and find something better to do with my time.

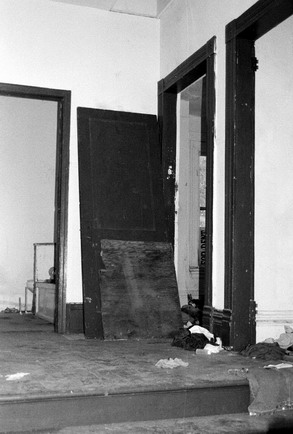

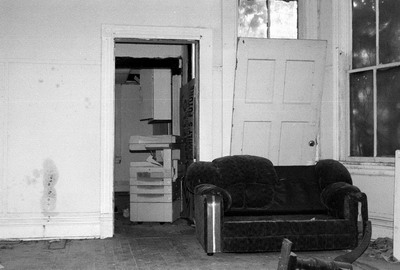

All the above photos were taken Spring 2010 inside three abandoned homes standing right next to each other in downtown Augusta, Georgia, USA.