Most of the ghost towns I visit have been written about by Philip Varney in his New Mexico's Best Ghost Towns: A Practical Guide. The problem is that this guide was first published in 1981 and thus many of his photographs and descriptions date from the late 1970's. When I go to check out one of these towns I usually find MUCH LESS than he did. Well, what do I expect? We're talking at least an additional three decades of exposure to elements both natural and manmade. One exception to this rule might be Chloride, currently pop. 11, which, after nearly disappearing totally, has been resurrected as a charming slice of history wwaaayy out in southwestern New Mexico. At some point I'll do a post on Chloride. On the other end of the spectrum is Yeso, a ghost town which actually looks pretty similar to how it must have when Varney stopped by. Although Yeso is not entirely a ghost town; a few people do live there and a functioning post office sits right across the street from the abandoned one.

Yeso sprang up along Yeso Creek, but the water was not fit for consumption. Yeso translates as "gypsum" or "chalk" in Spanish and you can't really drink a glass of dissolved gypsum without running into problems. But Yeso also had readily accessible groundwater which could be pumped for livestock and locomotive engines traveling the brand new Belen Cutoff. The cutoff re-routed trains through east-central New Mexico, away from the steep grades toward Colorado. One of the first frame train depots was built in Yeso, which was officially established in 1906, a year before completion of the Belen Cutoff.

The town did alright for awhile. A post office was constructed in 1909 and the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe (ATSF) railroad kept things going despite a lingering regional drought. Yeso quickly became a gathering place for the ranchers and handful of farmers in the area. Things got rough after WWII, when diesel locomotives were introduced and trains no longer had to stop in town to take on water. That was also about the time it finally became clear that the land around Yeso was really not very good for farming and might not be suited for much beyond grazing sheep. It had been an awfully dry few decades, too.

By the mid-1960’s, the school, which was built by the Works Progress Administration in 1940, closed as the last steam locomotives were retired. The old frame train depot now became one of the last of its kind to fold, shutting its doors for good in 1968. Most everyone packed up and moved to Fort Sumner, 22 miles to the east. Apparently four families opted to stay in Yeso and I have to wonder if their descendents occupy the few well-maintained homes abutting U.S. 60. Incidentally, Billy the Kid was killed in Fort Sumner and I'll eventually do a post on that infamous town, as well.

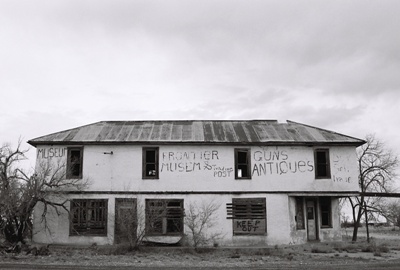

While much remains of Yeso, including the still-decaying remains of several houses--an entire abandoned neighborhood, more or less--and the Frontier "Musem" (once known as the Hotel Mesa, pictured at left), as well as the shell of the Super Service Drive In garage, there have been some casualties. What Varney describes as a possible gas station/garage/motel/residence complex on the east end of town has largely collapsed. This is unfortunate as he mentions that in the sidewalk in front of this structure was the date of construction, June 8, 1929, set in the cement in bottle caps. As far as I can tell, this bit of concrete is now buried under the collapsed walls of the large rock building. Too bad. Several other structures are also showing their years, so, if you’re going to visit, I still wouldn’t recommend waiting very long.

While much remains of Yeso, including the still-decaying remains of several houses--an entire abandoned neighborhood, more or less--and the Frontier "Musem" (once known as the Hotel Mesa, pictured at left), as well as the shell of the Super Service Drive In garage, there have been some casualties. What Varney describes as a possible gas station/garage/motel/residence complex on the east end of town has largely collapsed. This is unfortunate as he mentions that in the sidewalk in front of this structure was the date of construction, June 8, 1929, set in the cement in bottle caps. As far as I can tell, this bit of concrete is now buried under the collapsed walls of the large rock building. Too bad. Several other structures are also showing their years, so, if you’re going to visit, I still wouldn’t recommend waiting very long.Finally (and oddly), the spelling of Yeso was changed to a misspelling--Yesso--between 1912 and 1913. Anyone know why?

Info for this post came from Philip Varney (of course) and this little write-up on Ghosttowns.com. I also grabbed one fact from Dixie Boyle’s cool (and now hilariously expensive) book on U.S. Highway 60.

Happy holidays! There’s plenty of ground to cover in 2012.

I'd hoped to get inside but the house was boarded up tight. Apparently it had often been wide open, but when I got there thick plywood covered every entrance. All I could do was walk around the outside and take in some of the remaining architectural features. The back shed was accessible but uninteresting and a homeless person had recently taken up residence. After awhile I laid a hand on the 103-year-old house to pay my last respects and then headed home. On Monday, following a whim, I decided to stop by once again and saw that there would now be no problem getting inside. The house was already dark due to the boarded-up windows and the sun was setting, so I didn't have much time, but I tried to get a few decent shots. By the time you read this, the Werner-Gilchrist house will be no more, living on in a few photos and, of course, that episode of

I'd hoped to get inside but the house was boarded up tight. Apparently it had often been wide open, but when I got there thick plywood covered every entrance. All I could do was walk around the outside and take in some of the remaining architectural features. The back shed was accessible but uninteresting and a homeless person had recently taken up residence. After awhile I laid a hand on the 103-year-old house to pay my last respects and then headed home. On Monday, following a whim, I decided to stop by once again and saw that there would now be no problem getting inside. The house was already dark due to the boarded-up windows and the sun was setting, so I didn't have much time, but I tried to get a few decent shots. By the time you read this, the Werner-Gilchrist house will be no more, living on in a few photos and, of course, that episode of

The stuffed toys began to lose their stuffing, with the gorilla bleeding badly out of a large hole in its side. Once I found a collection of CD’s stacked in a corner of the concrete fence. They were not in cases, but were carefully tucked away beside some beer bottles. The music wasn’t what I would have expected, but was better, more obscure, and included the likes of Captain Beefheart, which seemed perfect. In the end, all that remained were some last weather-beaten stuffed animals tied to the tree. The demolition team took down not just those ragged creatures, but the entire tree as well. I wonder what their thoughts were as they considered the last hours of the Aztec Motel.

The stuffed toys began to lose their stuffing, with the gorilla bleeding badly out of a large hole in its side. Once I found a collection of CD’s stacked in a corner of the concrete fence. They were not in cases, but were carefully tucked away beside some beer bottles. The music wasn’t what I would have expected, but was better, more obscure, and included the likes of Captain Beefheart, which seemed perfect. In the end, all that remained were some last weather-beaten stuffed animals tied to the tree. The demolition team took down not just those ragged creatures, but the entire tree as well. I wonder what their thoughts were as they considered the last hours of the Aztec Motel.

The Aztec Motel was actually the first motel built on East Central Ave. There seems to be some disagreement as to whether it was built in 1931, 1932, or 1933, but it certainly pre-dated Route 66, which was not designated until 1937. Built in a style known as “Southwest Vernacular” and originally called the Aztec Auto Court, the motel had 13 units and three carports. The carports were walled-in sometime in the 1950’s and turned into four additional rooms. This is also when the original neon sign was replaced with the one that can still be seen beside the now-empty lot.

The Aztec Motel was actually the first motel built on East Central Ave. There seems to be some disagreement as to whether it was built in 1931, 1932, or 1933, but it certainly pre-dated Route 66, which was not designated until 1937. Built in a style known as “Southwest Vernacular” and originally called the Aztec Auto Court, the motel had 13 units and three carports. The carports were walled-in sometime in the 1950’s and turned into four additional rooms. This is also when the original neon sign was replaced with the one that can still be seen beside the now-empty lot. In any case, in 1991, Mohamed Natha bought the motel and worked to bring it back from the brink. In an effort to cut down on visits by hookers and their clients, as well as drug addicts and petty criminals, Natha began to rent only to long-term residents. A short time later the Aztec began to be extravagantly decorated with found items (of which I’ll say more next time) and underwent a kind of renaissance. The long-term residents were chiefly artists, free spirits, and assorted characters-about-town whose personalities became reflected in the motel itself as a genuine community developed.

In any case, in 1991, Mohamed Natha bought the motel and worked to bring it back from the brink. In an effort to cut down on visits by hookers and their clients, as well as drug addicts and petty criminals, Natha began to rent only to long-term residents. A short time later the Aztec began to be extravagantly decorated with found items (of which I’ll say more next time) and underwent a kind of renaissance. The long-term residents were chiefly artists, free spirits, and assorted characters-about-town whose personalities became reflected in the motel itself as a genuine community developed.

The Silver Moon Lodge, built in 1953, was at 918 Central Ave. SW., not too far from Old Town. The Silver Moon and the Central Park Deli, which was also located on the premises, closed for good on October 15, 2007 after a 54-year run. Then, in the absence of a development plan, the entire complex sat vacant until July of this year. Originally, the place was known as the Desert Skies Motor Hotel. After that, it became the Desert Inn Motor Hotel. Here is (UPDATE: was) a cool POSTCARD from that era. By the 1980’s, a third name change found the hotel billed as the Grand Western Motor Inn. Clyde and Goldie Taylor, who ran the Desert Inn in Santa Fe, owned the business around this time. Here’s one

The Silver Moon Lodge, built in 1953, was at 918 Central Ave. SW., not too far from Old Town. The Silver Moon and the Central Park Deli, which was also located on the premises, closed for good on October 15, 2007 after a 54-year run. Then, in the absence of a development plan, the entire complex sat vacant until July of this year. Originally, the place was known as the Desert Skies Motor Hotel. After that, it became the Desert Inn Motor Hotel. Here is (UPDATE: was) a cool POSTCARD from that era. By the 1980’s, a third name change found the hotel billed as the Grand Western Motor Inn. Clyde and Goldie Taylor, who ran the Desert Inn in Santa Fe, owned the business around this time. Here’s one

“You can't expect very much from cheap motels, but this place was pretty bad (and not super inexpensive). Everything in our room seemed like it was broken -- the bathroom lights, locks, closet hanger rod, toilet, and curtain rod. On top of that, our towels and all the chairs in the room had mysterious stains on it. The only reason why this place gets two stars instead of one is because the staff was so nice and responded quickly when we phoned about broken lights and busted locks. They also provide free shuttling to and from the airport.”

“You can't expect very much from cheap motels, but this place was pretty bad (and not super inexpensive). Everything in our room seemed like it was broken -- the bathroom lights, locks, closet hanger rod, toilet, and curtain rod. On top of that, our towels and all the chairs in the room had mysterious stains on it. The only reason why this place gets two stars instead of one is because the staff was so nice and responded quickly when we phoned about broken lights and busted locks. They also provide free shuttling to and from the airport.”

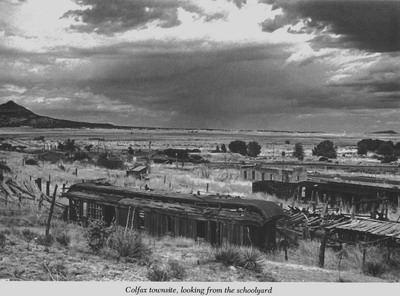

Then, on October 22, 1913, an explosion in Stag Canon Mine No. 2 sent fire spitting 100 feet out of the mouth of the mine. A dynamite charge had been mistakenly set, in breach of safety protocol, and ignited airborne coal dust. A massive rescue effort was undertaken with crews arriving from as far as El Paso, Texas, but only 23 miners survived. The final death toll numbered 263, making the Stag Canon Mine No. 2 disaster the 2nd worst in U.S. history. Two rescue workers were also killed in their efforts. Special white crosses were erected in the Dawson cemetery to mark the graves of those that lost their lives.

Then, on October 22, 1913, an explosion in Stag Canon Mine No. 2 sent fire spitting 100 feet out of the mouth of the mine. A dynamite charge had been mistakenly set, in breach of safety protocol, and ignited airborne coal dust. A massive rescue effort was undertaken with crews arriving from as far as El Paso, Texas, but only 23 miners survived. The final death toll numbered 263, making the Stag Canon Mine No. 2 disaster the 2nd worst in U.S. history. Two rescue workers were also killed in their efforts. Special white crosses were erected in the Dawson cemetery to mark the graves of those that lost their lives.

In that time things have changed a bit and I was not about to climb the gate, heavily posted with “No Trespassing” signs, and possibly try my luck with a ranch hand. But the cemetery, which was once just outside of town, is open to the public and is now the only visible remnant of Dawson. Family members still gather at the cemetery to reminisce and remember their loved ones. A number of the graves are well-kept with recently-placed flowers. But other graves are broken and forgotten. There are row upon row of names. Polish, Czech, Italian; many written in the native tongue. One lonely grave is of Marck Zamponi, a member of the “Wagoner 9 Engrs.” The stone simply says “Minnesota” (my home state) and there is an accompanying date of death: June 11, 1927. Did this man leave his family up north behind? Did they even know he was dead, let alone buried below a hill in a sooty coal town in northern New Mexico? After all these years, his story, like so many others, is forgotten and will never be told again.

In that time things have changed a bit and I was not about to climb the gate, heavily posted with “No Trespassing” signs, and possibly try my luck with a ranch hand. But the cemetery, which was once just outside of town, is open to the public and is now the only visible remnant of Dawson. Family members still gather at the cemetery to reminisce and remember their loved ones. A number of the graves are well-kept with recently-placed flowers. But other graves are broken and forgotten. There are row upon row of names. Polish, Czech, Italian; many written in the native tongue. One lonely grave is of Marck Zamponi, a member of the “Wagoner 9 Engrs.” The stone simply says “Minnesota” (my home state) and there is an accompanying date of death: June 11, 1927. Did this man leave his family up north behind? Did they even know he was dead, let alone buried below a hill in a sooty coal town in northern New Mexico? After all these years, his story, like so many others, is forgotten and will never be told again.

It’s been said that Lambert was Abraham Lincoln’s personal chef, but there is no hard evidence of this. On the other hand, it probably is true that, while living in Elizabethtown, Lambert was presented with a severed head. More on that grim tale can be found

It’s been said that Lambert was Abraham Lincoln’s personal chef, but there is no hard evidence of this. On the other hand, it probably is true that, while living in Elizabethtown, Lambert was presented with a severed head. More on that grim tale can be found

and thus there’s reason to suspect that Buffalo Bill never stayed at the hotel either. On the other hand, Buffalo Bill was said to be a personal friend of the Lambert’s, so the jury might still be out on that one. Legend has it that the Earp brothers and their wives spent three nights at the St James on their way to Tombstone and, you know, that just might be true. Clay Allison most certainly stayed many times, leaving the bodies behind to prove it. Bob Ford, the guy who shot Jesse James? Maybe. Ford is credited with shooting a man named Bob Curren in the St. James in 1882, the same year he shot Jesse. But I wouldn’t doubt that he actually came through later, on his move to Las Vegas, NM in 1884. In the early 20th century, Zane Grey definitely spent time at the hotel, writing some of Fighting Caravans in room 22. Other figures like Black Jack Ketchum and Doc Holliday? They were at times nearby, but your guess is as good as mine as to whether they really visited the St. James.

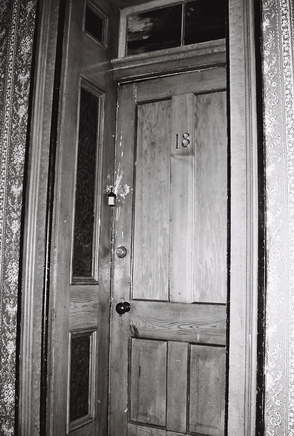

and thus there’s reason to suspect that Buffalo Bill never stayed at the hotel either. On the other hand, Buffalo Bill was said to be a personal friend of the Lambert’s, so the jury might still be out on that one. Legend has it that the Earp brothers and their wives spent three nights at the St James on their way to Tombstone and, you know, that just might be true. Clay Allison most certainly stayed many times, leaving the bodies behind to prove it. Bob Ford, the guy who shot Jesse James? Maybe. Ford is credited with shooting a man named Bob Curren in the St. James in 1882, the same year he shot Jesse. But I wouldn’t doubt that he actually came through later, on his move to Las Vegas, NM in 1884. In the early 20th century, Zane Grey definitely spent time at the hotel, writing some of Fighting Caravans in room 22. Other figures like Black Jack Ketchum and Doc Holliday? They were at times nearby, but your guess is as good as mine as to whether they really visited the St. James. Perhaps the most interesting spectral figure at the St. James is Thomas James (T.J.) Wright. T.J. Wright was reportedly killed upstairs in the card room, following an evening of gambling. One story has Lambert himself shooting Wright in the back as Wright walked away after Lambert had gambled (and lost) his entire hotel to T.J. I doubt that’s accurate, but, whatever the case, Wright was dead at the age of 22. Now, Wright’s violent spirit is said to occupy his old room, number 18. So many guests have reported being tormented by Wright’s ghost, some being physically hurt, that room 18 is now padlocked and guests are not allowed in. Our bartender said that he sometimes goes up to the room and has a glass of whiskey, leaving one behind for Mr. Wright.

Perhaps the most interesting spectral figure at the St. James is Thomas James (T.J.) Wright. T.J. Wright was reportedly killed upstairs in the card room, following an evening of gambling. One story has Lambert himself shooting Wright in the back as Wright walked away after Lambert had gambled (and lost) his entire hotel to T.J. I doubt that’s accurate, but, whatever the case, Wright was dead at the age of 22. Now, Wright’s violent spirit is said to occupy his old room, number 18. So many guests have reported being tormented by Wright’s ghost, some being physically hurt, that room 18 is now padlocked and guests are not allowed in. Our bartender said that he sometimes goes up to the room and has a glass of whiskey, leaving one behind for Mr. Wright.