Clayton, New Mexico is a little bit out of the way. You’re probably not going to just suddenly stumble into it. Unless you’re going to visit the barren place where New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Texas all meet, in which case, sure, maybe you will happen across it.

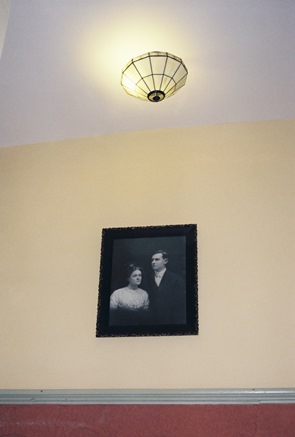

Despite its location, Clayton is famous for several things. There are lots of dinosaur footprints nearby. And a volcano, too. The lovely Eklund Hotel is there, established in 1892 and once the finest railroad hotel between Fort Worth and Denver. There are even two bullet holes still visible in the tin ceiling of the old saloon. That’s maybe not as impressive once you know that the shots were fired by excited supporters of President Warren G. Harding upon his election in 1920. Hey, no injuries were reported. But Clayton was also the site of what is widely agreed upon to be the most botched hanging in the West, that of Thomas Edward “Black Jack” Ketchum. I looked into it all on the frozen, windswept weekend before Thanksgiving while based at the Eklund.

(Above are the old headboards off the beds in the Eklund re-used as seat backs in the dining room.)

Black Jack was born in Texas and began leaving a trail of alleged crime in 1890, at age 27, right around the time he came to New Mexico. Possibly a soured love affair drove him off the rails. If so, crime must have already been in his genes

because his older brother, Sam, left his wife and family to become an outlaw, as well. I say Black Jack’s crimes were “alleged,” because, while he was connected to many robberies and dark occurrences over the years, including the famous disappearance of politician Albert Jennings Fountain and his young son, Henry, near Las Cruces, he was never convicted of anything until being sentenced to death for attempting to rob a train. This was also unusual as no one else in American history was ever executed for train robbery alone.

because his older brother, Sam, left his wife and family to become an outlaw, as well. I say Black Jack’s crimes were “alleged,” because, while he was connected to many robberies and dark occurrences over the years, including the famous disappearance of politician Albert Jennings Fountain and his young son, Henry, near Las Cruces, he was never convicted of anything until being sentenced to death for attempting to rob a train. This was also unusual as no one else in American history was ever executed for train robbery alone.Eventually Black Jack and his brother joined the dapper and charming Hole in the Wall Gang in the north-central part of the state, sometimes making a living ranching and, at other times, jockeying for position with Butch Cassidy’s other crew, the Wild Bunch.

On September 3, 1897, the Hole in the Wall Gang robbed a train between Folsom and Des Moines, NM. They did so again on July 11, 1899, but Black Jack did not participate in the second effort. After the second robbery, a gunfight ensued near Cimarron and Sam was badly wounded. A second shoot out occurred a few days later and a sheriff and deputy were killed. Sam was finally caught but died a short time later of his injuries in the Santa Fe Territorial Prison.

On August 16, 1899, Black Jack attempted to single-handedly rob the same train, unaware that his brother was recently dead from a similar idea. Black Jack boarded the engine, but mistakenly forced it to stop on a sharp turn where the cars with the loot could not be uncoupled. Meanwhile, the conductor, Frank Harrington, was getting sick of being robbed. He crept through the cars and shot at Black Jack, who returned fire. Black Jack missed; Harrington nearly severed Black Jack’s arm at the elbow. Black Jack fell off the train but was unable to get back on his horse.

The train quickly got moving again, leaving Black Jack to lie out all night until “help” arrived in the form of another train. He raised his gun as the conductor and brakeman approached him. They offered to shoot him right then if he wanted a fight, but he replied, "No boys, I am all done. Take me in." His arm was amputated in Trinidad, Colorado and then, restored to relative health, he was sent back to Clayton for trial. Convicted of “felonious assault upon a railway train,” Black Jack became the only person sentenced to death under the law, which was later overturned by the Supreme Court as carrying too severe a sentence.

Now, Clayton had never seen a hanging before and they weren’t quite sure what to do, besides sell tickets and tiny Black Jack dolls hanging from miniature gallows. The execution was delayed several times, but rumors of a plan to break Black Jack out of jail got a date finalized.

On April 26, 1901, after a further delay of several hours for continued fine-tuning of the gallows, Black Jack stood on the scaffold and these words are often said to have been his last: “I'll be in hell before you start breakfast, boys! Let her rip!” However, they’re probably apocryphal; he was executed around 1 p.m., closer to lunchtime anyway. The San Francisco Chronicle reported that Black Jack was somewhat more subdued, his legs trembling, saying only: "Good-by. Please dig my grave very deep. All right; hurry up." Still other accounts have simply, “Hurry up boys, get this over with.”

Whatever he said, Black Jack clearly wanted it all over with fast. The sheriff needed two swings of the hatchet to cut the rope, but the trap finally fell open and Black Jack dropped. However, the rope was too long and, possibly due to over-testing with a 200-pound sandbag, no longer had any elasticity. Thus, Black Jack was instantly decapitated, one of only three such occurrences over a few hundred years of recorded judicial hangings in the U.S. and Europe.

Photos exist of the gruesome aftermath, the separated head still contained in the black hood and lying in front of the one-armed corpse. The Chronicle noted that the heart clearly continued beating for awhile. Then, in another strange twist, Black Jack’s head was sewn back on his body before burial at 2:30 p.m. that day in Clayton’s Boothill. One wonders how much effort they put into the job. No one was ever executed in all of Union County again.

Photos exist of the gruesome aftermath, the separated head still contained in the black hood and lying in front of the one-armed corpse. The Chronicle noted that the heart clearly continued beating for awhile. Then, in another strange twist, Black Jack’s head was sewn back on his body before burial at 2:30 p.m. that day in Clayton’s Boothill. One wonders how much effort they put into the job. No one was ever executed in all of Union County again.Black Jack's grave was moved from the original Boothill to the current Clayton Cemetery in the 1930's. In the end, he got Shakespeare for an epitaph and still gets flowers over 100 years after his death. We should all be so lucky.

“And How His Audit Stands, Who Knows Save Heaven.”

The story or Thomas "Black Jack" Ketchum is widespread on the internet, although inaccuracies abound. Legends of America does a nice job and Allflictor.com reprints the San Francisco Chronicle article. Wikipedia isn’t bad either. Perhaps the oddest piece is at badhombres.com, where Black Jack’s great, great nephew provides history and insight found nowhere else. Whether it’s all true is anyone’s guess.

FEBRUARY 2014 UPDATE: Here at City of Dust we're always trying to get the story straight. Any research into Black Jack Ketchum's hanging will turn up a variety of quotations from his final moments and I went to some pains trying to sort out what he actually said. I believe his intended last words really were, "Goodbye, please dig my grave very deep. All right, hurry up." However, truth is always stranger than fiction and, in fact, Black Jack Ketchum seems to have said almost everything attributed to him and then some, just not all of it from the gallows.

The most famous and widely-quoted statement is, "I’ll be in hell before you start breakfast, boys! Let her rip!" That's almost correct. But it was not said immediately before he dropped and it was mostly not intended for just any "boys."

The first part of the quotation appears in the Santa Fe New Mexican, dated April 26, 1901, the day of the hanging, and it is directed toward Frank Harrington, the conductor who shot Black Jack's arm off. When Ketchum's lawyer was leaving his cell for presumably the last time, Black Jack told him, "Say, tell Harrington I'll meet him in hell for breakfast." This was after he'd requested to "be buried face down so Harrington can kiss my ass." The next morning, according to the New Mexican, he told Sheriff Garcia to "hurry up the hanging so he could get to hell in time for dinner."

The first part of the quotation appears in the Santa Fe New Mexican, dated April 26, 1901, the day of the hanging, and it is directed toward Frank Harrington, the conductor who shot Black Jack's arm off. When Ketchum's lawyer was leaving his cell for presumably the last time, Black Jack told him, "Say, tell Harrington I'll meet him in hell for breakfast." This was after he'd requested to "be buried face down so Harrington can kiss my ass." The next morning, according to the New Mexican, he told Sheriff Garcia to "hurry up the hanging so he could get to hell in time for dinner."The other part of the quotation comes from what truly were Black Jack's last words. Sheriff Garcia, apparently drunk, was having a hard time cutting the rope to open the gallows doors. The New Mexican records that Ketchum, nervous and impatient, said, "Let 'er go, boys. Let 'er go." It is said that Garcia's friend, Dick Franz, finally cut the rope and became a minor celebrity for it afterward.

Apparently Ketchum's headless body landed on its feet and even remained upright for a moment, spurting blood. Sheriff John McCandlass, visiting from Dalhart, Texas, held the corpse to the ground to stop the convulsions that followed. Five minutes is reportedly how long Black Jack's heart continued beating.

You probably didn't need to know all that. But you might be interested to know that Black Jack wrote a letter to President McKinley saying that innocent men were imprisoned for a robbery that Ketchum and his gang had committed at Steins Pass. He wouldn't say a word as to where his compatriots were at that time but maintained that he had never killed anyone and was a victim of mistaken identity, having been confused with another outlaw, Black Jack Christian, killed four years earlier. His last requests were music and female companionship. The former he received via violin and guitar. The latter was denied due to a lack of public funds with which to pay the companion. It was said that he did at least eat a hearty final dinner.

Oh, and his request to be buried face down? When Black Jack was exhumed in 1933 to be moved to the new Clayton cemetery his coffin was opened and it was found that this, too, had been denied. Then, as a final addendum, Teddy Roosevelt was presented with his Winchester 30-30 for some reason that I can't quite figure out.

Where did I find all this information? From what's probably the most complete and accurate description of Black Jack Ketchum's final days, Death on the Gallows: The Story of Legal Hangings in New Mexico, 1847-1923. There is also an informative unofficial brochure on Thomas Edward Ketchum written by Jerry Phillips that you can find around Clayton. I guess some stuff still hasn't quite made it to the internet.

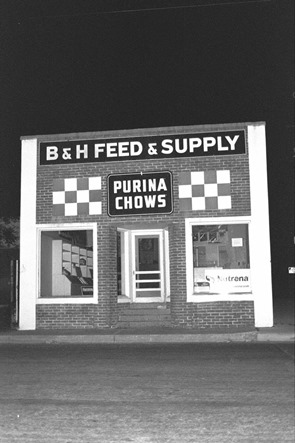

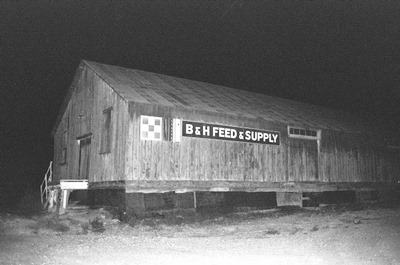

The photos of B H Feed & Supply were taken one night in late 2005. The shop is now the home of Crossroads Coffee Mill, a wonderful place for coffee and whatever else you might need of a morning. Be sure and stop by next time you're in Clayton. Tell them City of Dust sent you.