It was the middle of the morning on the Fourth of July and the rain was pounding down. Dirty, gray clouds hung low in the sky. Lightning flashed across the horizon and thunder rumbled ominously. I’d loaded the last of my belongings into the bed of my beat-up Ford Ranger and covered it all with a tarp. I hoped I’d done a good job with the tie-down and that the tarp wouldn’t leak and let the rain damage my cheap, particle-board furniture. Then I thought maybe it didn’t really matter after all.

I was leaving Greenville, South Carolina for Knoxville, Tennessee. I was happy to be getting out of Greenville, but not so sure I really wanted to be going to Knoxville. I’d accepted a nine-month appointment as a research technician in the Department of Chemistry at the University of Tennessee and figured, in the worst case, that it would buy me some more time to plot my next move. I’d just gotten onto Highway 276 outside of town when I saw a man walking up ahead on the shoulder of the road with his thumb out. The rain was relentless and the wipers struggled to keep the windshield clear, especially the passenger side one, which was rotted and squeaked gratingly.

I’d picked up hitchhikers in the past, usually out of boredom or a passing sense of recklessness. Only occasionally had a little bit of compassion entered into it. Every hitchhiker I’d ever given a ride to was at least a little crazy, and usually to the point where you felt you best pay close attention and not let the situation get away from you. But it was always an interesting experience. Once I picked up a guy in Baton Rouge who combined poignant stories of the family he missed badly back in Chattanooga with seamless interjections about a UFO attack he believed was imminent. I thought it took not just a little artistry to pull that off. There was another time someone actually wanted to be taken to a mental institution. He’d managed to wander out of the dayroom and, after a night spent roaming the streets, didn’t know how to get back. He gave me the name of the place and I recognized it. I’d had a cousin that spent some time there. I dropped the man at the front door within 20 minutes. By then the police had been searching for him for hours.

This time I was feeling bored AND reckless. As I passed the man I saw the water running down his face and into his thick beard. No hat. No jacket. That rain was cold. I guess then I felt a little compassion, too. I pulled to the shoulder and flicked on the hazards. The man ran up to the car, swung open the door, and dropped into the seat. He was soaked to the bone. He put a small, very wet, army green duffel bag on the floor. Hitchhikers and their bags. The man’s long, brown hair was plastered to his skull. He was wearing only a blue, flannel shirt, and I could see some tattoos peeking out around his wrists and neck. A lighter shirt would’ve been rendered transparent, providing a better look, but what ink I could see didn’t appear to have been done by a professional. He was also sporting a paunch that hung over his sopping jeans.

“I apologize,” he said, out of breath. “I’m gettin’ your truck all wet.”

“Don’t worry about it,” I replied, pulling back onto the highway. “If this truck gets either of us to where we want to go we can consider ourselves lucky. Speaking of which, where are you going?”

“Knoxville.” Then he began to cough violently and needed a little time to recover. After wiping his mouth with the back of his hand, he continued: “I’d ‘preciate whatever help you can give me in that direction. Only, when you drop me off, could I ask that you leave me at a gas station or someplace dry? I’m gonna die of pneumonia out there.”

The windows of the truck were quickly fogging up. I turned the defroster on full blast. “I’m going to Knoxville myself. I can take you all the way.”

The man seemed to somehow unspool from inside himself. He sank down into the seat with relief. “Brother, you’ll be doing a man that’s down on his luck a solid.” Then he held out his hand. “Name’s Terry, but my homeboys call me T-Dawg. You should, too.”

I shook his hand. It was rough and calloused and ice cold from the rain. “I’m Jack,” I told him. “Where are you coming from?”

T-Dawg didn’t miss a beat. “Prison,” he said. “A seven-year stretch.”

I couldn’t even pretend to be surprised, although I was a little alarmed. “Sorry to hear you were away. How long have you been out?”

He looked at his cheap plastic digital watch, seemingly still functioning despite the deluge. ”’Bout four hours. They transferred me to Greenville last week from Perry for some reason. They just let me out the door this mornin’ and I been walkin’ ever since.”

Now I was even more concerned, but I thought I hid it well. “So, this really is Independence Day for you.”

He paused and then laughed loudly. “Shit! I hadn’t even thought of that! You’re right. Hell yeah it is!”

I wanted to ask why he was in prison, but thought better of it. Instead, I said, “Did you do it?” and instantly regretted the words. I thought it would come off as funny, yet it only struck me as a much worse question.

But T-Dawg laughed even louder. “Man, NO ONE in prison did it. NO ONE!” Then he turned to the side window and wiped away some condensation. “But, yeah,” he added, somberly, “I did it.” As soon as he finished speaking he began to shiver and I switched over to the heater. He rubbed his hands in front of the vent. “Now I just want to see my ex-wife’s old lady and maybe cut the grass at her place, patch the roof, find out where my boy is at.”

Conversations with hitchhikers always seem to swing from jovial, if not entertaining, to dark and disturbing without a moment’s notice. Was T-Dawg really going straight from prison to mow the grass at his ex-wife’s mother’s house? And fix the roof, too? If he didn’t know where his boy was, then he must not have called ahead. I wondered what kind of trouble I was helping instigate. I only nodded.

T-Dawg dug into the top pocket of his shirt and pulled out a soaked pack of Camels. He opened the pack, saw there was no hope, and put it back in his pocket. I thought he’d want to know if I had a cigarette, but instead he asked, “So, how do you make a living?”

“I’m going to do some work for the chemistry department at UT-K. Just a nine-month contract and then who knows? The long-term is uncertain. Story of my life.” I thought the last two sentences might establish some sort of common ground between us. Maybe I was going to need it. But T-Dawg didn’t acknowledge any common ground. Instead, he leaned excitedly across the console. “Chemistry?! That so? Would you have access to maybe a pound of potassium nitrate?” I could’ve sworn he then bit his lip solely to keep from implicating himself further. He chewed at his beard for a few moments, as if deep in thought. “There’s this stump at my ex-wife’s mom’s place that I’d love to blow out of there.”

Again I nodded. “Well, I’d like to help, but I’m working with computers mostly. Data management and stuff. Plus, I haven’t even started yet.”

T-Dawg was clearly disappointed. “Ah, well. Maybe I can ask around a little.” Then he began to cough again.

We continued north through Hendersonville and the rain only seemed to come down harder. “This is going to put a damper on holiday picnics and fireworks,” I offered.

“No shit,” T-Dawg replied. “Do they still do the big display in K-Town? The one where they light the whole damn bridge up?”

I told him I thought that was “Boomsday,” the Labor Day fireworks display in Knoxville, said to be the biggest in the country. But it’d been years since I’d spent any real time in the town and I couldn’t be sure anymore. It seemed impossible to think that they’d be able to have any fireworks at all in weather like this.

T-Dawg stopped shivering and eventually tiny dry patches began to form on his shirt. His hair was drying, too. Walking in that rain must’ve been exhausting, and with a little warmth now T-Dawg fell asleep. His head was against the window, mouth open, and every now and then he made a noise that was something like a groan. I wasn’t about to wake him until it was necessary. As we neared Asheville and I-40 westbound, I felt more relaxed with T-Dawg asleep.

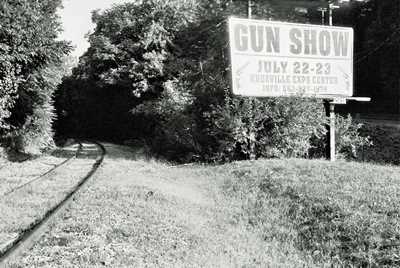

When we approached the outskirts of Knoxville I gave T-Dawg a light tap on the shoulder. I let him take a few moments to remember where--and, perhaps, who--he was, and then asked how to get to where he wanted to go. He told me to exit I-40 at Western Avenue and head northwest. Then, as we came beside the railroad tracks, he indicated a narrow dirt road. We turned right and crossed the tracks into a trailer park that seemed to have been dropped haphazardly into a scraggly pine forest. The rain would’ve kept anyone inside but, judging from the number of satellite dishes, the gravel lanes might’ve been empty of people most of the time anyway. At the end of one street T-Dawg told me to pull onto a worn patch of grass in front of a worn-looking mobile home. I did, but rather than get out, T-Dawg sat there looking at the beaten trailer, saying nothing. Finally, he put his hand on my arm and said, “Come on in. I’d like you to meet someone. Maybe get you a drink, too.”

I searched for an excuse, but with no one waiting for me and nothing much that needed doing, I went blank. Before I could make something up, T-Dawg squeezed my arm and said, “You really oughta come inside.” He looked at me intently, his long, dirty hair and matted beard masking his true expression. Somewhere in this seemed to be the air of a threat.

“Ok,” I said, and opened my door. At least the rain had begun to let up. T-Dawg grabbed his duffel and swung out of the passenger side. As we walked to the trailer, he pointed to the wet grass which, while sparse, did approach my knees in places, making my shoes and jeans damp.

“See this shit?” he said. “I knew it’d still be like this. Always needs mowing. There just ain’t been no one around can do it.” Then he motioned toward the hacked and weathered remains of a pine tree along the side of the trailer. “There’s that fuckin’ stump. If I cain’t blow it out, maybe I can dig some ‘round the roots and chain it to a truck.”

As he ascended the rotten wooden stairs to the warped and peeling door, I dropped back. I couldn’t guess what was about to happen, but I kind of expected it to be bad. T-Dawg knocked and we waited. In a few moments, the door opened slightly and a woman with long, curly, blonde hair peered out while leaving the chain latched. From that brief glimpse I guessed she was in her 50’s, but it was hard to tell. She might’ve been younger. It looked like life could age you fast around this place. All at once her eyes got big and her mouth made a large “O”. The door slammed shut and I immediately felt queasy. I had no idea what I would do if things turned violent. Then I heard the chain rattle and the door swung open. The woman stepped out, threw her arms wide, and yelled, “Oh, my God! Terry!” She was crying. T-Dawg wrapped his arms around her tenderly and I looked away. Not far off a crow was perched in a pine tree, keeping dry in the rain. It was watching us, tilting its head this way and that, quizzically. It wasn’t the only one that was bemused.

It seemed that entire minutes passed before the woman stepped back to take in T-Dawg. Her face was red and damp. She was a little overweight, but now seemed friendly and warm. She was wearing a blue Wal-Mart employee vest. I couldn’t see T-Dawg’s reaction to any of this.

“Why didn’t you tell me?” the woman finally said. “You know I would’ve found a way to get you.”

“I couldn’t trouble ya,” T-Dawg answered. “Ya’ll got enough to do. Anyway, I figured it might best be a surprise.” He stopped and turned to me, still standing below the steps. “My friend Jack gave me a ride. He was heading this way anyhow.”

The woman looked at me as if I’d appeared out of nowhere. “Oh!” she exclaimed, but didn’t go further.

I took a couple steps toward her and extended my hand. “Jack Crawford.”

“Betty Johnson,” she replied, taking my hand very lightly. “Thank you for bringing Terry home. It’s nice to meet you.”

“You, too, ma’am.”

“Well, let’s not stand ‘round gettin’ wet.” T-Dawg motioned us inside as the rain started again. Part of me wanted nothing more than to turn around and get back in my truck but, on the other hand, what was going on between T-Dawg and Betty had gotten my attention.

Inside the trailer were plastic pails and buckets of all sizes and descriptions positioned here and there over the stained and buckled linoleum of the kitchen, scattered across the dingy carpet of the living room, and no doubt trailing off into the bedrooms, and probably the bathroom, too. As the rain strengthened, “plops” seemed to erupt from every direction, a soft, percussive effect without apparent pattern or rhythm at first, but then somehow seeming to cohere. Betty offered me a yellow vinyl chair that was torn, exposing a dirty piece of foam.

“Now, what can I get you after that drive?” she said. “Beer? Iced tea? How ‘bout a sandwich?”

Though I was hungry I couldn’t imagine asking Betty to make me a sandwich, so I just answered, “Iced tea, please.”

Betty dug around in the refrigerator, the back of her blue vest emblazoned with the white words, “How May I Help You?”

T-Dawg asked, “Where’s Tammy?”

Betty began to pour some tea from a big plastic jug. “Memphis, last I heard from her. But that was about six months ago.”

“How’d she sound?”

“About the same as last time you all talked.” Then Betty put the glass in front of me and glanced quickly at T-Dawg. “Maybe a mite worse.”

T-Dawg chewed on his beard and rubbed his hands. Betty asked if he wanted anything, but he shook his head. I took a sip of the iced tea. Plops seemed to be coming from everywhere at once now as the rain pinged harder on the roof. After a few more moments, T-Dawg said, “Can I see Cody?”

Betty was quiet. More rain came down from the sky and more water fell in the buckets. “Of course,” she answered, finally. “I think you need to.”

Then she went off to the back of the trailer and, while T-Dawg and I waited, I heard her talking to someone on the phone. But she spoke quietly and I couldn’t make out the words. I could see T-Dawg straining to pick up the conversation, but then he seemed to give up and leaned toward me. “Hey, could you gimme a lift to one other place? It ain’t far.”

I felt like I had no choice. “Sure. No problem.” I took another drink of tea.

Betty came back out looking serious. “You can go over anytime you want. They’re at home. I’d take you now but I’m afraid I’m already going to be late for work. They don’t accept no excuses at that place.”

T-Dawg made a noise that seemed to be an affirmation and told Betty that I’d drive him. To where, I didn’t know. I finished my tea as T-Dawg grabbed his bag and moved toward the door. He told Betty he’d see her shortly. I stood up and thanked Betty and then we were back outside in the rain, walking quickly to the truck.

We backtracked to I-40 and went south across the roiling, brown Tennessee River on Highway 441. T-Dawg told me to exit on Maryville Pike, but aside from the few directions, he said nothing and only stared out the window at the gloom. Every now and then he coughed a bit more. It sounded like it was getting worse. The wipers swooshed and squeaked. I wasn’t about to say anything.

Finally, T-Dawg told me to slow down and then pointed out a narrow street. I made a left turn and we quickly pulled up beside another trailer. This time the yard was well-manicured with a garden gnome sitting by the front steps and an ornamental wrought iron deer underneath an adjacent pine. It didn’t look like T-Dawg would need to do any work at this place.

I shut off the car and T-Dawg clutched his bag. “Betty’s older sis, Mary, lives here.”

Now at least I knew where we were. It seemed like he wanted to say something more, but he opened the door and got out into the rain. I did likewise. I saw a prim-looking woman’s face through a window and then the door opened before T-Dawg could knock. Mary was thin, dressed in jeans and wearing cowboy boots. Her brown hair was cut short and she looked younger than her sister. She put her arms around T-Dawg, but the reaction was cooler than Betty’s. If she was at all surprised to see him, she didn’t show it.

“This is Jack,” T-Dawg said, pointing to me still standing on the walk, getting wet. I just waved. I felt better closer to the truck.

Mary seemed to be trying to size me up. She was probably wondering why I was there at all. Then she gave a slight shrug, said, “Nice to meet you,” and told us both to come inside.

The trailer was immaculate and warm. A crockpot burbled on a counter in the kitchen and the smell of beef stew was heavy. My stomach rumbled. A framed piece of needlepoint by the door read, “God Bless This Home and All Who Enter,” and some country music played low in the background. “Dixieland Delight” by Alabama.

Mary offered me a seat, then looked at T-Dawg and said, “I’ll go get him.” She went down the hallway and in less than a minute returned with a boy beside her. He was thin and his black t-shirt said “TENNESSEE” across the front in orange block letters. His hair was exactly the color of T-Dawg’s and as unruly. His eyes were wide, although he avoided looking directly at anyone. He couldn’t have been ten years old and he was scared. Mary stopped directly across the kitchen from us and put her arm around the boy’s shoulder.

“Cody, your daddy’s here.” The boy seemed to draw up into himself. “He’s come to see you.”

T-Dawg put his duffel down and took a few slow steps toward Cody. Then he put a hand on his son’s head, tousling his hair gently. “How you been, lil’ man? You taking care of things while I been gone?”

It seemed impossible, but the boy’s eyes got wider. His mouth opened, but instead of speaking he pulled away from Mary’s side and ran back down the hallway.

T-Dawg looked stunned, and then like he might cry. He made a movement toward the hall but Mary stopped him. “Let the boy be. He needs some time. He’s just scared.”

T-Dawg snorted. “Scair’t of his own daddy.”

Suddenly it was like a dark cloud passed over Mary’s face. “The last time he saw you he could barely say ‘daddy’,” she hissed, coldly. “You’re lucky he even remembers you enough to be scared.” T-Dawg put a hand against the wall as if to brace himself. “Why wouldn’t you let him see you all these years, anyway? A boy needs his father, even if his father’s in prison.”

T-Dawg stared at the shiny linoleum floor. He seemed dissipated. “Because I didn’t want him to see me there. I didn’t want him to have memories of his daddy like that.”

“So you thought no memories at all would be better?” T-Dawg just shook his head. “He’s acting out at school, you know. Gets in fights. Won’t do what the teachers ask him. ADHD was what the doctor said. He gave us some medication.”

T-Dawg took a minute to process this. “Does the medication help?”

“It seems to, I think. At least when I can get him to take the pills. Sometimes he hides them under his tongue and spits them out when I’m not looking. Now I make him open his mouth and show me.”

T-Dawg went back to staring at the floor. Mary softened. “But he’s a good kid. He’s got a good heart. You’ll like him. You just need to make sure he likes you.”

T-Dawg truly did start crying. Now I stared at the floor.

“What are your plans, Terry?” asked Mary, after a while.

“Oh, I ain’t going nowhere,” said T-Dawg with a sniffle.

“Good,” Mary replied, then repeated, almost at a whisper: “Good.”

T-Dawg started coughing again and walked through the kitchen and out the door without another word. Mary watched him, then turned and went back down the hall. I didn’t know what else to do, so I followed T-Dawg outside. The rain had eased again. He was sitting on the bottom stair step. The aluminum storm door rattled, but he didn’t seem to hear me. I stopped as he pounded his big fist into his right thigh. Hard. Then he did it again. I waited a few moments before scuffing my foot on the wooden step to get his attention. He turned and looked at me like I was a ghost, then ran his palm quickly across his face. “Hey, man, I want to thank you. You been good to me.” He reached out his hand and I took it. I felt an unexpected surge of emotion. I came down the steps and wasn’t sure what to do. “Have a good Fourth,” I said, and instantly felt like an idiot.

T-Dawg looked confused but then grinned, his stained teeth showing behind his beard. “Yeah, God bless America, man!”

Then I walked to my truck, got in, and pulled away. T-Dawg gave me a wave. I was barely back to Maryville Pike when the rain started falling harder once more. It was beginning to get dark so I decided to make a quick stop at Taco Bell and then head over to see what was going on at World’s Fair Park. I‘d finally remembered that that was where they had the Fourth of July celebration in Knoxville, and I wanted to know if maybe they’d come up with a way to shoot off fireworks even in rain like this.

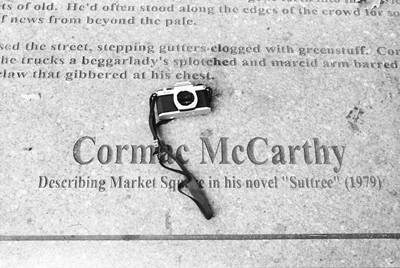

It's been a long time since I stepped back from ghost towns for a moment and posted a story. February 21, 2014, to be exact, when I put up a piece set in Socorro County, New Mexico, called "The Monsoon." Not only does the story above take place (mostly) in Knoxville, Tennessee, but the photos all came from there, as well. On the perhaps rather off-chance that you want more of this kind of thing, you can always check out the City of Dust collection, A Loss For Words, on Amazon.com.

Next time we're off to the ghost town of Lake Valley, New Mexico, once home of the famous Bridal Chamber Mine.