As threatened last time, I'm gonna do a post of outtakes. This way I can put up some photos that didn't make it initially, revisit some posts you may have missed the first time, and wax on about some completely random topics. In fact, if you've been searching for a soundtrack for City of Dust (I know, just bear with me here), this post will provide some suggestions. I mentioned Blind Willie McTell briefly while we were hanging out in the Phinizy Swamp, but I think I'll say a little more about the most famous bluesman of the Augusta area. He's even got his own festival. I've got a feeling I'll stray a little outside of Georgia by the end, but what the heck. The photo is from the intersection of Greene St. and East Boundary Rd. A different look at the dead gas station.

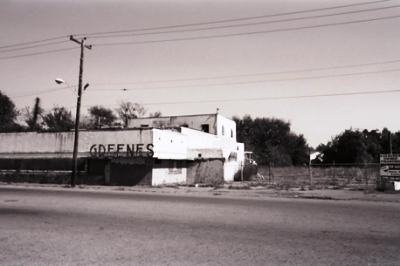

Now, when I'm talking about the blues, I'm not talking about what those goateed guys are playing down at the corner bar on Saturday night (Blues Hammer, anyone?). I'm talking about acoustic music from the Mississippi Delta, music that seems to have risen up out of the mud of the parched floodplain. There's not many of those bluesmen left, but the ones that are around all seem to be on Fat Possum Records. The most famous of these players from the Augusta area was indeed Blind Willie McTell, born in 1898 nine miles south of Thomson, GA, which is about half an hour outside Augusta on I-20 W. This is another shot from Greene St. and East Boundary. A more properly forlorn look at Greene's Night Club and Diner.

In 1907, Willie moved with his mother to Statesboro, but she died three years later and he went back to Thomson. McTell began playing on a six string, but later switched to a twelve, which he used for most of his recordings. His parents were both reportedly good players, so it's likely he learned from them. Remember, music was one of the only ways a blind youngster like Willie would ever make any money.

Even though he moved to Atlanta in late 1927, Willie travelled frequently between Statesboro and Thomson throughout his life, playing every small town in between, often staying for a week or two in each. He recorded in New York and Chicago, but also Augusta. Eventually he started to attain some degree of fame and people in the rural areas considered Willie a star. Blind Willie would play anywhere: tobacco warehouses, livery stables, hot dogs stands. I once went to the Morton Theater in Athens just because Blind Willie McTell played there. Actually, the play was pretty good that night. The picture above is of... Well, I don't know what it is. It has bars on the windows, so let's say it was a jail. It's off Highway 125, just outside Beech Island, at the corner of Silver Bluff Rd., I believe. Anyone have any info?

Blind Willie had a bit of a ragtime influence in his playing, which made some tunes a little, um, jaunty, but he could moan and cry with the best of 'em. He wrote some classic Georgia anthems, such as "Atlanta Strut," "Georgia Rag," and "Savannah Mama." "Lord Send Me An Angel" contains the line, "All these Georgia women won't let mister Mac-Tell rest." Random aside: It was soul singer James Carr who threatened a lady friend in song with deportation to the Peach State, singing, "I'm gonna send you right back to Georgia." Carr is from Memphis and is second in my book only to Otis Redding for pleadin' and sobbin' soul music, although a history of severe mental problems derailed his career long ago. Anyway, around WWII the demand for blues singers and their records declined dramatically. McTell was generally found singing on Atlanta street corners throughout the 1940's. This photo is from inside the "Beech Island Jail." Post-jailbreak, apparently.

By the 1950's Willie had fallen on hard times. He was broke, his health was worsening, and he was becoming prone to falls, a condition exacerbated by a fondness for corn whiskey (in the early 1920's he'd operated his own moonshine still). He was now singing songs at night for amorous couples parked behind the Blue Lantern Club in Atlanta and living in a small place off an alley. In 1956, a record store owner in ATL tried to coax Willie into recording a few numbers at his store. Willie refused, mostly, bitter and upset about the way he'd been treated by record companies. But, one evening, the shop owner plied McTell with some corn whiskey and got him to record twelve tracks and some tales. Three years later, on August 19, 1959, Blind Willie McTell was dead, buried as Eddie McTier, a combination of old family names that would've made it hard to track down his grave on your own. Shortly after, the record store owner went into his attic, throwing out badly damaged reel-to-reel tapes. Only one tape, at the bottom of a pile of trash, was intact: McTell's last session. It's good. His voice is a bit think and slurred from the whiskey, but he still had it. Bob Dylan knows. Here's a couch in the garage of the abandoned house overlooking Getzen's Pond.

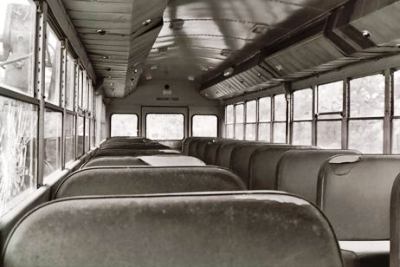

Now, I really love bottleneck slide playing. A lot. These guys were tough and slides were made by smashing a bottle, then melting the jagged edges of the neck over a fire until it comfortably fit the ring or pinky finger. Slide playing wasn't really a regional phenomenon; players popped up here and there, sometimes in clusters. Augusta was the early home of slide player Eugene "Buddy" Moss, who recorded such songs as "Hard Road Blues," and "Hard Times Blues." In Atlanta by 1928, Moss teamed up with Blind Willie McTell and other Atlanta guitarists, including Curly Weaver and Barbecue Bob. Things were looking good for Moss when he murdered his wife and went to prison for five years. Time passed Buddy by and the recordings following his release didn't sell. During the folk revival, when players such as Leadbelly and Bukka White attained some fame and (a little) fortune, Buddy was so paranoid and suspicious that he refused to speak with most interviewers. Blind Willie McTell, of course, never had such a chance. The view from the front of the bus at the Aiken-Augusta junkyard.

For my money, the finest slide player wasn't from the South proper, but Temple, Texas. Blind Willie Johnson, who recorded in Dallas, New Orleans, and Atlanta, was blinded as a child when his stepmother threw lye in his face. She was upset about a beating his father had given her for cheating on him. In an unfathomable bit of musical serendipity, in Marlin, Texas, during the 1920's, Blind Willie Johnson and Blind Lemon Jefferson played against each other on opposing street corners.

Those two corners, then, would've been the absolute center of the blues at the time. Johnson's recordings were exclusively spirituals, and with the quavering, stinging slide they are some of the most haunting songs I've ever heard. His recording of "Dark Was the Night...Cold Was the Ground," featuring no words, only Willie's soft humming of the melody, is one of the most evocative songs in the history of American music. Incidentally, Willie's version of this song formed the basis of the soundtrack for what I consider one of the best movies ever made, Wim Wender's Paris, Texas. It's easy to see why Ry Cooder based an entire soundtrack around the song. Hell, you could base your life around the song. Unfortunately, the Depression cut Willie's recording career short. In the 1940's, the house Willie shared with his wife burned down. With nowhere else to go, the couple slept on their old mattresses, still wet from the firehoses, covering themselves with newspaper. Willie contracted pneumonia as a result and, being broke and blind, no hospital would see him. Thus the world's greatest slide guitar player died, leaving thirty songs, one photo, and the charred bridge of his guitar, burned in the fire, as the only evidence. Last stop, the end of the line.

Those two corners, then, would've been the absolute center of the blues at the time. Johnson's recordings were exclusively spirituals, and with the quavering, stinging slide they are some of the most haunting songs I've ever heard. His recording of "Dark Was the Night...Cold Was the Ground," featuring no words, only Willie's soft humming of the melody, is one of the most evocative songs in the history of American music. Incidentally, Willie's version of this song formed the basis of the soundtrack for what I consider one of the best movies ever made, Wim Wender's Paris, Texas. It's easy to see why Ry Cooder based an entire soundtrack around the song. Hell, you could base your life around the song. Unfortunately, the Depression cut Willie's recording career short. In the 1940's, the house Willie shared with his wife burned down. With nowhere else to go, the couple slept on their old mattresses, still wet from the firehoses, covering themselves with newspaper. Willie contracted pneumonia as a result and, being broke and blind, no hospital would see him. Thus the world's greatest slide guitar player died, leaving thirty songs, one photo, and the charred bridge of his guitar, burned in the fire, as the only evidence. Last stop, the end of the line.But, all told, I think the greatest of the Delta/Country blues musicians remains Robert Johnson. It's a cliche, really, and I wish I could point to someone more obscure, maybe Memphis Minnie or Blind Blake, but I have to agree with decrepit English rock stars and middle-aged men who wear berets. Born in Hazlehurst, Mississippi, music provided the only way Johnson saw out of sharecropping and, after his first wife died during childbirth at the age of 16, he never stopped moving, hopping trains or hitching rides at whim to anywhere, anytime of the day or night. Johnson's unreal playing and lyrics seemed to appear fully-formed, leading to speculation that he'd sold his soul to the devil at the crossroads. Indeed, it does sometimes sound like two or three guitarists are playing.

And he was protective of his technique, leaving a room in mid-song if he thought someone was studying his moves. He also developed a taste for whiskey and women. Upon arrival in a town, Johnson would look for the homeliest woman around, knowing that if he treated her nice she'd give him food, shelter, liquor, and a few other things as well. But it was his womanizing that was his undoing, and one night, in the fall of 1938, Johnson began eyeing a woman at a juke joint gig. He was playing with Sonny Boy Williamson, who warned him that things were getting heavy, going so far as to knock an open bottle of whiskey someone had given Johnson out of his hand. Johnson was furious at this waste of good alcohol, and when the next bottle came by, he drank. Within three days he was dead, poisoned by the husband of the woman he was flirting with. He was 27 years old. The picture is of a single cypress tree, taken while knee deep in water below the Savannah River rapids.

And he was protective of his technique, leaving a room in mid-song if he thought someone was studying his moves. He also developed a taste for whiskey and women. Upon arrival in a town, Johnson would look for the homeliest woman around, knowing that if he treated her nice she'd give him food, shelter, liquor, and a few other things as well. But it was his womanizing that was his undoing, and one night, in the fall of 1938, Johnson began eyeing a woman at a juke joint gig. He was playing with Sonny Boy Williamson, who warned him that things were getting heavy, going so far as to knock an open bottle of whiskey someone had given Johnson out of his hand. Johnson was furious at this waste of good alcohol, and when the next bottle came by, he drank. Within three days he was dead, poisoned by the husband of the woman he was flirting with. He was 27 years old. The picture is of a single cypress tree, taken while knee deep in water below the Savannah River rapids.Robert Johnson recorded only 41 songs, just 29 different titles. Otherwise, there are two photos and a death certificate. Hearing him moan, "I've got to keep movin', I've got to keep movin', blues fallin' down like hail, blues falling down like hail," as he creeps into "Hellhound on My Trail," there seems no doubt that the man was haunted. Or, perhaps, in his own words, "drunk and driven." How about this, from "Me and the Devil Blues": "Early this mornin', when you knocked upon my door, early this mornin', ooh, when you knocked upon my door, and I said, 'Hello Satan, I believe it's time to go.'" I ask you, who wrote songs like that in 1937?

Don't believe in ghosts? You should. Every time I'm stopped for a train, and it's late at night, I'll see the flashing red lights of the crossing guard, turn to watch the lights of the train fade into the distance, and hum, "Well, the blue light was my blues, and the red light was my mind. All my love's in vain." Melodramatic? Well, nothing's made sense since Brad and Jen broke up, has it? So, sleep it off in a comfy chair behind an old Chinese restaurant near Washington Rd. Oh yeah, virtually every artist I've mentioned can be found on re-releases through Columbia Records Roots n' Blues series. They've done some nice packages and, sure, I admit to borrowing from the occasional liner note for this post. There's audio snippets for each track from just about every release, so you can hear a few seconds of Robert Johnson and Blind Willie (both of 'em) doing their thing.

Don't believe in ghosts? You should. Every time I'm stopped for a train, and it's late at night, I'll see the flashing red lights of the crossing guard, turn to watch the lights of the train fade into the distance, and hum, "Well, the blue light was my blues, and the red light was my mind. All my love's in vain." Melodramatic? Well, nothing's made sense since Brad and Jen broke up, has it? So, sleep it off in a comfy chair behind an old Chinese restaurant near Washington Rd. Oh yeah, virtually every artist I've mentioned can be found on re-releases through Columbia Records Roots n' Blues series. They've done some nice packages and, sure, I admit to borrowing from the occasional liner note for this post. There's audio snippets for each track from just about every release, so you can hear a few seconds of Robert Johnson and Blind Willie (both of 'em) doing their thing.

1 comment:

Mr. John,

You failed to mention Skip James or Son House. How can this be? Your jaunty Piedmont and dusty Texas blues has got the best of you.

Mr. Zak

Post a Comment