skip to main |

skip to sidebar

(CONTINUED) I considered my options. There was plenty of good food around, but I wasn’t hungry. I could take a walk down to Sutro baths, but I was tired. I turned on the TV and flicked through some channels. Oprah came on and I muttered, “Fuck it,” and flicked the set off. I got my phone out and made the call. Anne answered on the second ring.

“Hi. It’s me. How are you?”

“I’m fine. You’ve been away?”

I couldn’t read her voice. Not entirely surprised, not entirely unsurprised. A little bit upset, maybe a tiny bit pleased. Maybe.

“Yeah, I just got back in town. I’ve been in the desert.”

It seemed like the line had gone dead. I wondered if she’d hung up. I was about to say something when she asked, “Writing?”

“Trying. It’s not going so well though.”

She coughed. “Well, it hasn’t gone well for a long time, has it?”

That was a bad sign. I decided to just get to it.

“Listen, I want to see you. “

More silence.

“Will you see me?”

A few moments passed. There was some rustling on the other end. I expected that she’d ask why I wanted to see her, but she did not. Just: “Okay.”

“Tonight?” I asked.

“Where?’

“The park. The usual spot.”

“I need an hour.”

“Alright.”

She hung up without saying goodbye. I didn’t know what I felt but it didn’t feel good.

It would take me the better part of an hour to get to Stow Lake on foot, so I headed out the door. As usual, the park was filled with people and I was continuously stepping to the side of the small paved trail to let bikers and joggers pass. A tattered brown plastic tarp had been hung in some bushes and four homeless men sat staring out sullenly from underneath it at the passersby. Two men were smoking, one was taking a pull off a bottle in a brown paper bag, and the fourth was looking out at the path with a startling intensity, as if the mundane proceedings before him were nearly beyond his belief.

I arrived at the lake before Anne and sat on a bench by the boat rental. It was strange to be in this spot, this lake that had once served as a place of respite and now seemed anything but comforting. When Anne approached I stood up and we embraced quickly, the familiar made awkward.  She was wearing an old blue wool sweater her brother had given her for Christmas years ago and jeans. Her blonde hair was pulled tightly back away from her face in a style she usually only wore when cleaning the house or exercising. I wondered if there was some significance in her appearance. She seemed tired and this made her look a bit older than she was, her green eyes shining a little in the sunlight. For all that she looked beautiful, as I thought she always did. If only beauty were enough. I waited for her to say something, but she remained quiet.

She was wearing an old blue wool sweater her brother had given her for Christmas years ago and jeans. Her blonde hair was pulled tightly back away from her face in a style she usually only wore when cleaning the house or exercising. I wondered if there was some significance in her appearance. She seemed tired and this made her look a bit older than she was, her green eyes shining a little in the sunlight. For all that she looked beautiful, as I thought she always did. If only beauty were enough. I waited for her to say something, but she remained quiet.

“It’s nice to see you,” I said finally, as we began to walk around the lake.

“’Nice,’ huh? Well, it’s good to know where I stand at the moment. I can’t always be sure.”

“You know that’s not true,” I replied. “You know how I feel.”

“I guess I do,” she said, but didn’t say anymore.

We walked for a few minutes in silence. I wasn’t sure what I wanted to say. It was hard to recall why I’d come in the first place. All the words that had been so clear and definite, so important, suddenly threatened to vanish into the air.

“I just wanted to say goodbye…” I began, but she interrupted.

“I’m pretty sure you’ve already said that.”

I took a second to regroup. “No, I mean, I want to say goodbye. For good.”

She stopped walking. “Where are you going?”

I looked out at the lake. A few ducks were bobbing back and forth on the water. A blue paddle boat was out, its occupants pedaling in silent complicity. The air was getting cooler as evening approached. The park seemed a picture of serenity, everything within it wheeling and flowing and pumping in unison.

When Anne and I had been married and I was becoming relatively successful I used to tease her about the dark side of being a writer, warning her of the day my artistic temperament would inevitably take a turn for the hopelessly morose. “It’s the prerogative of all writers to occasionally go off the deep end,” I’d say. “It’s really the only way to maintain your status in the literary community. And if someday you find yourself unable to come back from the brink, at least you know it’ll be a boon for your estate. Hell, death is the only hope some authors have of ever getting their books back in print. You’ll become very rich when I flip out.”

Anne would laugh and tell me to shut up and get back to work. But she knew my family history—an uncle who hanged himself, a grandmother committed to an asylum, a father whose only form of entertainment was drinking cheap gin until he felt moved to throw the furniture through the windows—and, though she never said it, I’m sure she was sometimes afraid I was serious. And I WAS serious. Or I’d at least convinced myself I was serious. I considered the poison in my blood to be the source of my deepest inspiration and my twisted genes my greatest literary gift. If I couldn’t bleed that madness onto the page then I might as well pack it in and wait out the rest of my days in bed with a bottle of cognac in one hand and a .38 special in the other. At least I’d be in good company.

Anne seemed to be searching my face, then, she laughed: “God, you can’t be serious.”

I felt a little bit hurt by that, but tried not to let it show. “I’m not saying I’m going to put a gun in my mouth. I’m just saying the road looks like it might be heading over a cliff and maybe I won’t be able to stop the car.”

She started walking again, quickly. “Or maybe you just don’t want to.”

We continued on. In all the years we’d been together I’d seen her upset many times. I’d seen her weep for two days straight when her father died and all I could do was hold her in my arms. I’d heard her use language that would make a sailor blush when someone cut her off in traffic. But always there was some outward manifestation, some obvious expression of her feelings. Now she was silent, uncommunicative, and I regretted coming. Ruben had been right; I should’ve just left her alone.

She crossed over the footbridge, a little bit ahead of me, then turned and leaned against it, watching the water. The ducks paddled and quacked a bit. I watched a kite dip and bob above the trees.

“I’m pregnant.”

The red kite spun and dove, then rose again, its yellow tail fluttering behind.

“You’ve been seeing someone?”

She turned to me and looked into my eyes. She was a foot from my face but the distance between us had vanished. I knew at that instant that we were bound together for eternity, that whatever may come, be it separation, death, or nameless oblivion, that somehow, in some terrible, wonderful, incomprehensible way, our destinies were one. I could leave her, but she would never be gone from me.

“It’s yours,” she said, but by then I already knew.

I turned back to look at the water. I couldn’t see the kite for a moment then it rocketed up from behind a tree. “Two months?” I asked.

“Fifty-eight days.”

The divorce had already been finalized by then. Whether we’d made love out of sorrow or desire or fear or anger or just plain habit I couldn’t have said. She’d lain in bed crying as I’d put my clothes on and walked out one last time.

“You should’ve told me.”

“Would you have answered the phone?”

I would’ve liked to have said that yes, of course, I would’ve answered the phone. But I couldn’t say that. “You could’ve left a message.”

She shook her head, livid. “I have some dignity left, you know. You didn’t get everything.”

Minutes passed during which I felt despondent, jubilant, angry, hopeful, ecstatic, and fearful, until it all seemed to blend and I couldn’t tell one from another.

“I’m going to have it,” Anne said, finally.

“I know.”

“So you can decide how involved you want to be. I will only ask that for the sake of your unborn child you not write yourself a final chapter that our baby will someday be ashamed to read.”

My head ached. I felt sick to my stomach. I took Anne’s hand in mine and held it. “Okay,” I nodded. “Okay.”

We walked back to the dock, the paddle boats all tied up and rocking slightly on the lake. Some were red and some were blue. Anne and I embraced again, but it felt different, inevitable, unavoidable.

“I need to think about this,” I said. “I need a little time.”

“Do whatever you think you need to do. I’m prepared to raise this baby by myself.”

I nodded and started to leave. I’d gone about 20 feet when I turned around, and watched her walk away. After a few moments she looked behind her and waved weakly. A sad smile crossed her face for a moment then she continued on into the deepening dusk. (CONTINUED)

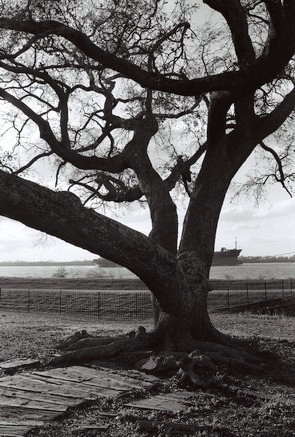

All photos of SF, CA.

(CONTINUED) Ruben showed up almost an hour late. What could I say? I didn’t really mind. I’d stood outside of baggage claim watching the cars go by, sucking exhaust fumes, and wondering what I was doing. Everything began to feel unreal and I wasn’t sure if that was because of the carbon monoxide or something more serious. In any case, I was glad to see Ruben when he pulled up in his rusty old pick-up truck. It was the only vehicle he’d ever owned, as far as I knew. I threw my bag in the bed and climbed in. Ruben grabbed my hand and gave me a thump on the shoulder.

“Tom! Good to see you.”

“Nice to see you, too,” I said, grinning, as the truck sputtered and died.

He dropped the clutch into neutral and revved the engine a few times, then got it back into gear and the truck lurched out of the terminal. It seemed to take all Ruben’s concentration to keep the truck going and it wasn’t until we were safely on the 101 that he spoke again: “This ol’ truck takes a little coaxing, but I wouldn’t have it any other way.” Silence again. Then he turned to me, serious: “What the fuck are you doing?”

I laughed, though nothing was funny. Finally, I shook my head: “I don’t know. Maybe I need some closure.”

Ruben downshifted hard and the truck bumped and wheezed. “Ah, bullshit! There’s no such thing as closure and you know it. Don’t you read your own damn books? Why don’t you just leave her alone? She’s had a hard time.”

I felt my stomach drop. A few unpleasant scenarios went through my mind. “Have you seen her?”

Ruben looked to his left, out the window. “Nah, but I’ve heard from friends.” The truck groaned, struggling to pass a bus. “I don’t think she wants to see me either.”

“You don’t think she’ll see me?”

Ruben turned off the 101 and into downtown. As the truck slowed for a light it smelled like something was burning. Ruben sniffed then turned on the heat full, although it was at least 70 degrees out. “Yeah, she’ll see you.”

We drove down Geary Boulevard toward the ocean. The afternoon traffic was getting heavy. Four busses were ahead of us, all #38, and we stopped as streams of passengers got off and on. “I gotta get to work soon,” Ruben said. “You can drive me in if you want. Take the truck…”

“Oh, no,” I said. “Thanks, but no thanks. I don’t think she’ll run for anyone but you.”

Ruben’s place was near the Golden Gate Park and within walking distance of the ocean. He’d lived there as long as I’d known him. He always said there was no reason to go anywhere else. As I watched him drive off to work in a cloud of white exhaust, I could hear the gulls wheeling overhead and the air was cool and damp. A few tall trees swayed slightly on the horizon. I figured he was right. (CONTINUED)

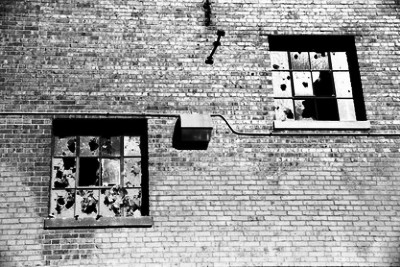

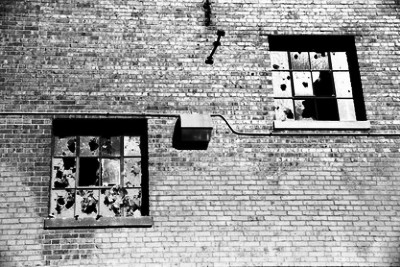

All photos of St. Paul, MN.

(CONTINUED) I got to the gate as the plane was boarding and slept through most of the short flight, but by the time we landed at SFO I felt worse than I had at departure. At the airport I called my friend Ruben. He answered on the seventh ring.

“Hello?” He sounded groggy, but I guessed I probably did too.

“Hey Ruben, it’s Tom.”

“Tom! What the hell? Where are you?”

“I’m at SFO”

“SFO? Where are you going?”

“I’m not going, I’m returning. I need to see Anne.”

He paused for a moment. “You’re going to see her?”

“Yeah, I want to.”

Ruben sighed. “Are you sure it’s a good idea? The papers are signed and the rings are off. It’s all over. Let it go. It was your decision anyway.”

I didn’t want to get into it. Not there. Not yet. “Listen, Ruben, I was just wondering if you could give me a ride.”

Another pause, then: “Hell, you could’ve given me some notice. I’m not even dressed yet.” Ruben worked nights at the post office loading and unloading trucks. He’d had the job since I’d known him, which at this point was about 12 years. He continued: “Not only that, you could’ve let someone know you were leaving. What were you doing?”

“I was writing.” It was sort of true.

“Well, finally…”

I cut him off. “Listen, I was only wondering if you could pick me up. I can wait awhile. Just as long as you can show up sometime this afternoon.”

He laughed. “Yeah, sure. Let me get dressed and I’ll be there in an hour. You going back to your place?”

“Nah, I let the lease go and moved my stuff into storage.”

“You did? Man, that was a nice place. You’ll never get rent that cheap again. So where…?”

“I was thinking your couch might be available.”

Ruben groaned. “Shit. Alright, I’ll see you outside baggage claim in an hour.”

I picked up my bag and went to get some overpriced pizza. At the table next to me a woman in what I guessed to be her mid-thirties was talking to a man at least fifteen years her senior. She spoke slowly, her words measured. “Honey, do you think you can make it to the counter? Or you can tell me what you want and I’ll get it for you.”

“I don’t want that garbage.” His voice cracked. His bloodless face was covered in short, gray whiskers. “I ain’t hungry.”

The woman continued: “But you should eat. We have a long flight and they don’t have much to eat on the plane.” She spoke like she was frightened, as if a single unanticipated word or action on her part might cause the man to suddenly explode, as he’d no doubt done many times before. Or maybe he’d crumble to dust. I thought it was like watching someone working around a plug of dynamite that now had only the power to destroy itself yet remained just as volatile.

“Hell, I might be dead before we get there…”

The woman choked back a sob and I turned away. Then I heard the man say, softening, “Ah, I’m sorry. Baby, I’ll make it. It’s just these hospitals and the damn doctors and their bullshit.” His voice began to rise again, but he forced it down. “I’m wore out. But I’ll be okay. I promise you that.”

I looked over again and saw that he’d taken her hands in his. His arms trembled slightly as he squeezed her fingers gently in his palms. “Just get me a slice of pepperoni and a glass of ice water.”

The woman went to the counter and I stole one last glance at the man. I was worried he’d notice me, but instead he had his head in his hands, his withered fingers working through thin, greasy hair. I got up and went outside to wait for Ruben and noticed the difference immediately. The air was damp and cool and the sun dipped behind gray clouds. I wondered if there’d be fog in the morning. At least in one way I was out of the desert. (CONTINUED)

All photos of Tucson, AZ.

(CONTINUED) I was making my way out of Santa Fe, passing by the plaza in the center of the city, when I saw the grey-eyed girl sitting on a bench. Sleep deprivation can make me overconfident and blustery and wholly irrational. A little bit insane, really. Besides that, I don’t believe in coincidence. So, I turned down a side street, jumped out of the car, and made my way back to the plaza. She was still on the bench when I approached and I tried to think of what I’d say but was too distracted by HER to pull my thoughts together. Dressed in jeans and the same black leather coat, her brown hair pulled back, and now wearing glasses, I was reminded of why I’d spied on her from the San Miguel Mission in the first place. With that episode in mind, I decided to gamble.

“Excuse me, I’m looking for the Pink Adobe Restaurant. Do you know where it is?"

She looked at me, but I could detect not a glimmer of recognition. Beside her on the bench was a paperback copy of Moby Dick.

“Yeah, just follow Water St. here down to Old Santa Fe Trail and take a right. It’s only a few blocks.”

I’d ignored every word she’d said trying to come up with my next line. “Ah, thanks,” I replied. A moment passed while I weighed my options. Then: “Moby Dick, eh? Wonderful book. One of my favorites.”

She picked the book off the bench and looked at it. “Some friends of mine started a book club. We’re only reading the classics. Nobody ever seems to read them unless they’re forced to.”

I laughed. “I’ve always thought school beats any love for literature out of most people. I mean, Moby Dick can represent whatever, but why not just let people make up their own minds. After all, it’s fine if it’s just a big, smart fish.” I was running out of time. I had to bait the hook, so to speak. “Anyway, I read Moby Dick whenever I’m looking for inspiration for my own work.” I held my breath and thought, “Ask, c’mon, ask.” A second passed.

“Are you a teacher?” Bingo.

“No, I’m a writer.”

She sat up a bit on the bench. “Really? What kind of stuff do you write?”

I wanted to say that right then I was writing nothing, that I’d sunk so far down that maybe calling myself a writer had become a lie. Instead, I said breezily, “Oh, fiction. Mostly I guess you’d say they’re morality tales of a sort. Not wildly popular in terms of sales, but the critics are kind to me, and I’ve found a loyal audience.” I didn’t mention that I suspected I’d probably lost that audience for good.

Then I got a break: “You know,” she said, “some of my friends in the book club are working on their own stuff. I think they’d love it if you stopped in to give some pointers. We’re meeting at noon.”

“Are you writing?” I asked.

“No,” she laughed. “I’ve never written a thing.”

Too bad, I thought. But I had to go to Albuquerque anyway. After all, I had a plane to catch.

“Unfortunately, I’m flying out in a few hours.”

She shrugged. “Oh well. It was a thought.”

But I wasn’t going to just walk away. “I’ll be back though.” I had no idea whether that was true or not. There was still no sign she remembered me from the Mission, even after my initial prompt. “Why don’t I give you my number and you can call me when you’re going to have another meeting and I’ll see if I can make it.”

She took a pen out of her pocket and wrote my name and number on the back page of Moby Dick.

“Tom Gould,” she repeated. “Would I find your books at stores around here?”

“Well, it’d be Thomas, and, yeah, you probably would. At least at the more run down ones.” I smiled, then looked at my watch. “Listen, I have to go, but please call me when you’re getting together again.” Then I lied again: “I love to talk about writing.”

“I’ll call,” she said. “We’ll probably meet the first Tuesday of next month. I’m Julie, by the way.”

“Very nice to meet you, Julie,” I replied, then waved goodbye and walked quickly back to my car, abandoning even the pretense of going to the Pink Adobe. Now I’d be late to Albuquerque, but I thought I’d still make my flight in time.

I pulled into long term parking at the Albuquerque airport, next to a Buick Skylark with a flat back tire and six months of grime covering it. I wondered if my car would eventually join it, a forsaken vehicle that’d lost its owner. I looked wistfully at the black 1974 Jaguar XKE that I’d bought with my first real book advance.  Actually, it had taken more than just the advance, but at that time I‘d figured I’d made it, that the money would just keep rolling in. Of course, I’d been wrong. Yet I still loved the sleek and speedy reminder of my folly and now regretted not cleaning off the thick layer of desert dust that had accumulated over the last weeks. I ran a finger over the trunk and left a clean, black trail. I hesitated. It seemed I now suddenly had two reasons to stay in Santa Fe and just one to leave. I shook my head: that one reason alone was bigger than all the other reasons there could possibly be all put together. Suddenly I was very tired. I hoped I could sleep on the plane. I grabbed my bag and ran for the terminal. (CONTINUED)

Actually, it had taken more than just the advance, but at that time I‘d figured I’d made it, that the money would just keep rolling in. Of course, I’d been wrong. Yet I still loved the sleek and speedy reminder of my folly and now regretted not cleaning off the thick layer of desert dust that had accumulated over the last weeks. I ran a finger over the trunk and left a clean, black trail. I hesitated. It seemed I now suddenly had two reasons to stay in Santa Fe and just one to leave. I shook my head: that one reason alone was bigger than all the other reasons there could possibly be all put together. Suddenly I was very tired. I hoped I could sleep on the plane. I grabbed my bag and ran for the terminal. (CONTINUED)

Top photo is Tucson, AZ, obviously, and the middle shot is Gray County Wind Farm, Montezuma, KS. The bottom pic is from near Mammoth, AZ. Photos taken on expired movie film stock.

(CONTINUED) I drove back to the motel but couldn’t sleep, despite the beer. I lay down on the bed and looked at the dark ceiling and wondered why it was impossible for people to change. By the age of twelve I’d known this to be true—that who you were was who you were always going to be—because by that age I’d already hoped to be someone different than I’d been at eight or ten and instead I’d felt just the same. And again, lying in a motel bed in New Mexico, decades later, I was still the same. The problems were different now, more adult, perhaps, but they sprang from the same place that had once shaped an angry child. That child would not be banished but hid behind artifice and cloaked itself in deception, always waiting to return.

I'm not a late-night person and never have been. I might sometimes stay up past midnight, but if I'm not asleep by 2 AM I know I'm in trouble. My mind seems to wander into the darkest recesses, conjuring fantastic visions of what could be and what never should be. To be awake between the hours of 3 AM and 5 AM is, for me, to be lowered into the depths of hell, an utter torment. This is the hour of the wolf, when death seems to stand beside the bed and angels hang softly in the air, their eyes sorrowful, their outstretched hands empty, out of reach. Morning becomes the only blessing and the greatest curse. Many times I’ve been out of bed and at the bathroom mirror by 5:30, the dark, sunken eyes and ashen face clearly my own, yet I stare, lost, as if my own gaze might somehow change the hammered countenance thrown back at me. But I am me. Always me.

So it was on this morning as I dressed and showered, half-alive and wondering what I was doing. The dawn soon began to work its quiet magic, however, and the cock-eyed world that had arisen in the darkness slowly began to right itself. I recalled a fragment of a dream—though I did not recall sleeping—in which I was alone in a deserted city, amongst burnt-out buildings and piles of debris. I wandered down buckled streets and entered vacant tenements in search of assistance. But I could find no one. In the trash-strewn parking lot of a sprawling apartment complex I found a red phone.  A wire snaked from the back of the phone through the lot and up the stairs into the gutted building. I lifted the receiver off the cradle and heard a dial tone. I was instantly euphoric, a bubble of well-being rising from my stomach into my chest. But that joy disappeared just as quickly as I tried to recall what number I needed to dial. Again and again I punched numbers and again and again a woman’s voice, a robotic recording, told me that I was not allowed to contact this party, to please hang up and try another number. I tried the connection at the back of the phone and the wire broke off in my hand. The phone went dead. Just then a large man dressed in filthy rags began to stagger toward me, bellowing angrily, “Man, you better not have broken that phone! You better not!” Frantically, I tried to fix the phone as the man approached but I could not. I remember the fear, but that is all I remember. Then, nothing.

A wire snaked from the back of the phone through the lot and up the stairs into the gutted building. I lifted the receiver off the cradle and heard a dial tone. I was instantly euphoric, a bubble of well-being rising from my stomach into my chest. But that joy disappeared just as quickly as I tried to recall what number I needed to dial. Again and again I punched numbers and again and again a woman’s voice, a robotic recording, told me that I was not allowed to contact this party, to please hang up and try another number. I tried the connection at the back of the phone and the wire broke off in my hand. The phone went dead. Just then a large man dressed in filthy rags began to stagger toward me, bellowing angrily, “Man, you better not have broken that phone! You better not!” Frantically, I tried to fix the phone as the man approached but I could not. I remember the fear, but that is all I remember. Then, nothing.

I put my things in my suitcase and left ten dollars for the maid. I didn’t really believe people did that anymore, but it felt strangely desperate and reckless and so I did it anyway. The day was like almost every day in the desert: warm, cloudless, bright. I started the car and headed for Albuquerque. (CONTINUED)

Top photo is the San Xavier del Bac Mission, AZ, and the middle shot is somewhere on U.S. Highway 56, between Clayton and Springer, NM. The bottom pic is Tucson, AZ.

(CONTINUED) I didn’t go after the grey-eyed girl. Either she didn’t deserve me or I didn’t deserve her. I couldn’t decide which sounded better to me. And I couldn’t keep that other face out of my mind for long. No surprise there. I walked past the coffee shop and looked in the window. The grey-eyed girl was inside, at the first table by the door. I think the word is “fetching.” I smiled and waved, but if she reacted I didn’t notice. I kept on walking.

I went back to my hotel and made a phone call. A man answered, so I hung up. I made another call and bought a plane ticket. I wasn’t sure if I was looking to finally obtain my own desperately waylaid salvation or personally ensure someone else's ultimate destruction. At that moment I wasn’t even sure if the two events were necessarily exclusive of one another or if the one absolutely required the other. I hardly cared.

I drove to a battered honky-tonk just off the road out of Santa Fe, the Broken Spur. Inside it was dark save for a few beer signs and a couple naked bulbs above the bar and stage, upon which a band was playing old country songs. Lefty Frizzell, Buck Owens, Townes van Zandt. A few ragged couples tottered listlessly on the warped and stained dance floor. I ordered a beer and bought a pack of cigarettes, though I hadn't smoked in years. When in Rome, I figured.  I sat in a corner and watched the band, a pretty decent if glum-looking four-piece, who forsook all unnecessary stage banter as they moved woozily from one tune to the next. As the opening chords to "Galveston" rang out, I noticed three guys at a table on the far side of the dance floor. One of them had a patchy, unkempt beard and long, brown, stringy hair hanging down his shoulders. He was wearing what looked like a leather trench coat, similar to the kind ranchers might wear. Only, he was no cowboy. At the table with him were a skinny guy in a jean jacket and Pabst hat and another guy with long, brown hair and sunglasses perched on top of his head despite the sun having been down for hours. They were all probably in their late-twenties, although aging quickly and looking a little older than I guessed they really were. On the table were sixteen bottles of Lone Star, which I took the time to count twice.

I sat in a corner and watched the band, a pretty decent if glum-looking four-piece, who forsook all unnecessary stage banter as they moved woozily from one tune to the next. As the opening chords to "Galveston" rang out, I noticed three guys at a table on the far side of the dance floor. One of them had a patchy, unkempt beard and long, brown, stringy hair hanging down his shoulders. He was wearing what looked like a leather trench coat, similar to the kind ranchers might wear. Only, he was no cowboy. At the table with him were a skinny guy in a jean jacket and Pabst hat and another guy with long, brown hair and sunglasses perched on top of his head despite the sun having been down for hours. They were all probably in their late-twenties, although aging quickly and looking a little older than I guessed they really were. On the table were sixteen bottles of Lone Star, which I took the time to count twice.

On my side of the dance floor were two young girls, barely old enough to get in the place, if indeed they were old enough, each awkwardly sipping a single beer. One was very thin--too thin--with a drawn look and jutting cheekbones partially hidden by the black hair that fell over her face. Her friend was blonde and slightly overweight, heavily done-up in eyeliner and lipstick. I watched the three men eye the two girls from across the floor and eventually the guy in the trench coat came over and asked the blonde girl to dance. She giggled, smiled at her friend--who seemed utterly bored--and stood up.

The band, apparently without an uptempo song in their repertoire, lurched into “Silver Wings,” and the man pulled the girl close. She moved her feet tentatively, barely inches from his boots. When you want or need something--money, shelter, food, sex, or worse--the best and quickest way to get it is to prey on longing, uncertainty, and self-doubt. That is, you look for weakness. I knew as I watched the man dance with this girl that he’d found what he was looking for. And he knew it too. He nodded at his friends and they got up and walked over to the other girl and took turns dancing with her. Not one of those three seemed to be enjoying themselves. A few songs later I saw the man in the trench coat run a hand down the blonde girl’s ass. She just kept painfully shuffling from side to side, her arms wrapped around him.

The band took a break and the girl came back to her friend and told her they were leaving. By now the other two guys had gone back to sullenly pulling on their beers back at their own table. The skinny girl rolled her eyes, but got up wordlessly and followed her friend over to the three men. The guy in the trench coat put his arm around the blonde girl’s shoulder and grinned as he led everyone out the door. I wondered just how long it would take the girl to regret this night. Would she regret it tomorrow? Next week? Next month? Whatever the case, I knew she most certainly would regret it. But sometimes you have no choice but to make decisions that are wrong, take chances that you shouldn’t. Sometimes those are the only options you’ve been given and there's nothing else but to pick one hell or another. I ordered one more beer, hoping it would help me sleep, and started for the door just as the band was getting into “By the Time I Get to Phoenix.” It seemed to fit, even though I wasn’t going to Phoenix and I wasn’t leaving. There was simply no place left to leave. (CONTINUED)

All photos are of Tucson, AZ.

I was dining--alone, as I now always did--at the Pink Adobe in Santa Fe. I’d heard that Sam Shepard ate there regularly when he was living in town and, since I liked his stuff well enough, I was hoping some of the inspiration would rub off on me. It had been some time since I’d come up with anything usable—at least anything I’d dare show anyone—and I was getting desperate. Actually, I was desperate in more ways than just that one. Awhile back all of my moorings had been cut and since then I’d been staying out in the desert, moving from one town to the next as boredom or panic dictated. Mostly I’d been staying on the outskirts of slightly-seedy, sand-choked little towns like Winslow, AZ, Española, NM, and Elko, NV. But for the last few days I’d gone a bit upscale.

I’d actually begun to think that being monolingual was my main problem. Aside from the ubiquitous Spanish, all around me I heard Russian, French, German, and even ancient Indian dialects that tribal law stated could not be written down or recorded. It had occurred to me that, for the first time in my life, English was failing me and perhaps these other languages contained the words I wanted. But then I figured that the language required to say whatever it was I thought I needed to say probably didn’t even exist and, anyway, I was certainly in no shape to invent it.

I was mulling over these and other similar thoughts, feeling suitably dour as I worked at my enchiladas, when I noticed a boy and girl through the window. Or, rather, I noticed the girl. Chestnut brown hair, black leather coat, dark blue wool skirt, and light grey stockings. As I watched her talk to this boy I became transfixed. She seemed very serious and did not smile, although he occasionally did. I watched them for some time until I had finished my meal and paid for it.

I walked across the Old Santa Fe Trail, looking at the girl as I did. Our eyes met and I held my glance a beat longer than would be usual, then walked up the steps to the San Miguel Mission. I stood out front of the old church and looked down on the couple. To give myself cover, every now and then I pretended to check my watch and look impatiently up and down the street. After a short time the two embraced and, as the girl rested her head on the boys shoulder, she looked directly at me. I held her stare and could see that her eyes, seeming now to me quite willful, were a soft grey, the same color as her stockings. Very nice, I thought. But was the boy a friend, brother, or lover? Not that I really cared. A guy I knew once said that boyfriends are a little like herpes: they tend to go away for awhile. Of course, that guy was dead now and I never had been able to find out just what had happened, although I'd been told a gun had been involved.

The two parted and I watched the girl walk down the street and go into a coffee shop. I thought for a moment. I knew that if I went after her, regardless of what happened or did not happen—because, let’s face it, nothing in this world is a sure thing—I’d hate myself for it. Then again, self-hatred was an emotion I’d recently taken to cultivating nearly to the exclusion of all others. I think it was probably right then that a series of events was put into motion that I would indeed come to dearly regret. Yet I hesitated and for a brief instant on that cool, clear fall day, another face flickered warmly in my mind. Quickly I pushed it away and thought again of those soft grey eyes before starting down the road. (CONTINUED)

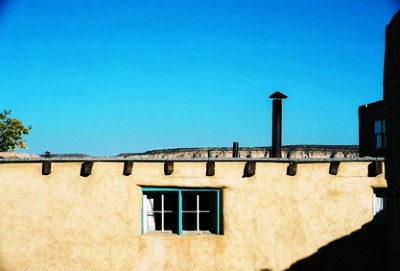

I know, photos of Santa Fe, NM would've probably made more sense here, but instead it's more shots from Acoma Pueblo, Sky City, NM. Well, except the bottom one, which is Petrified Forest National Park, AZ.

Shelly and I are at the Waffle House. It’s early and we’ve been up all night. There are a number of reasons why we haven't slept. All of them are bad. Shelly’s staring at me bleary-eyed and anxious. She’s wearing the same blue dress she wore yesterday. It’s a dress I used to love seeing her in. And taking her out of. But right now I’m feeling damp and wrung-out and sick to my stomach.

Our waitress comes over to take our order. She’s young and nervous and her name is Danielle. I guess that it’s her first day. Shelly orders coffee, two eggs, and toast. There is no cheer in her voice, only fear and exhaustion, like sandpaper, catching at her throat, each word a brittle, dead leaf. I try to sound pleasant, like me and Shelly are just two people out for a normal breakfast, while I order a pecan waffle. But as soon as I say the words the thought of butter and syrup and fried batter makes me want to retch.

When Danielle flips her hand over to write on the order pad I see two thick scars across her right wrist—widthwise, not lengthwise. Whether these cuts then were simply a cry for attention or the result of a fundamental lack of understanding as far as the basics of physiology go I cannot say. In any case, Danielle smiles perkily and says, “Be right up, ‘kay guys?!”

Danielle’s departure leaves Shelly and me in silence. I try to think of something to say but nothing comes to mind. For hours, Shelly has been telling me things that I’ve tried to convince her are simply not true. In response, she’s told me that truth, once and for all, now has to be the same for both of us. Just before we came into the restaurant I’d said that I didn’t think truth could ever be exactly the same for any two people. She just looked at me and said, “You make me sad.” It was difficult for me to admit that, right there, might indeed have been a solid truth, cold, objective, and utterly removed from any necessity of interpretation.

I hear Danielle call the woman at the hash brown station “mom” just as a man steps to the counter. A waitress tells him he can sit anywhere, but the man only shakes his head nervously and mumbles something I don’t understand. The waitress seems startled and the man says something that sounds to me like “cowboy.” He starts to fidget. The waitress frowns. “What’s that, hon’?” she asks. “Comfrey,” he replies. The waitress is silent. I realize that the man is retarded, though probably only mildly, and it’s not immediately obvious. I turn to Shelly, but she has also begun to follow the exchange. “Commie,” says the man quietly. The woman looks to another waitress for help, but the other waitress only smiles, making the woman giggle a little.  The man notices this, closes his eyes tightly, as if it was difficult, then opens them and screams, “Collie! Collie! Collie!” The restaurant goes dead quiet. Everyone turns to look. Seconds pass. Waffles begin to burn. Hashbrowns go unsmothered and uncovered. “Collie!” he screams again and, with his balled right hand, begins to punch himself in the face. Four, five, six times the man strikes himself, in the cheek, the mouth, the eye. Finally, he pulls his fist back one last time but, instead of hitting himself, he throws a handful of change at the counter. Coins explode through the kitchen and dining area, so many that he must’ve been intending to pay mostly in pennies. In tears, the man points to a mug and says, “Cobby!” The waitress is stunned. “Coffee?” she whispers. Tears flow down the man’s face. Thick red welts have risen on his forehead. “Yuh!” he yells, but turns to leave the restaurant. As he exits the door he punches the frame and screams again, then runs across the parking lot, around a truck, and out of view.

The man notices this, closes his eyes tightly, as if it was difficult, then opens them and screams, “Collie! Collie! Collie!” The restaurant goes dead quiet. Everyone turns to look. Seconds pass. Waffles begin to burn. Hashbrowns go unsmothered and uncovered. “Collie!” he screams again and, with his balled right hand, begins to punch himself in the face. Four, five, six times the man strikes himself, in the cheek, the mouth, the eye. Finally, he pulls his fist back one last time but, instead of hitting himself, he throws a handful of change at the counter. Coins explode through the kitchen and dining area, so many that he must’ve been intending to pay mostly in pennies. In tears, the man points to a mug and says, “Cobby!” The waitress is stunned. “Coffee?” she whispers. Tears flow down the man’s face. Thick red welts have risen on his forehead. “Yuh!” he yells, but turns to leave the restaurant. As he exits the door he punches the frame and screams again, then runs across the parking lot, around a truck, and out of view.

There is no way to restore normalcy to the Waffle House. A man puts some bills on the counter and rises, most of his meal uneaten. Then another couple leaves. Still no one speaks. I turn to Shelly, but she is already getting up, the tears already beginning. I look at Danielle, but she is frozen, her mouth hanging open, as a few other waitresses begin to talk amongst themselves and a cook scrapes seared eggs off the skillet. I motion to Danielle, but she does not see me. So, I pay for our food, the food we never even saw. It’s just as well, I think. I didn’t want to eat anyway. I leave a nice tip for Danielle in the hope that she’ll show up for work again tomorrow morning. But tomorrow morning is a long way off and there are other tragedies to attend to, so I head off into the glimmering sunlight after Shelly.

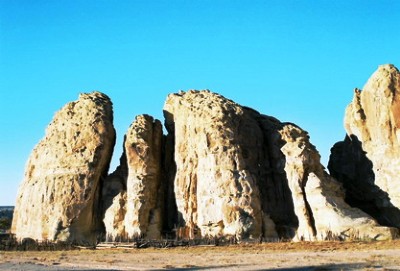

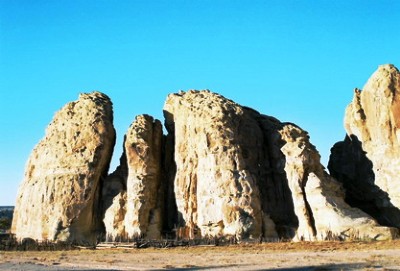

All photos are from Acoma Pueblo, Sky City, New Mexico. The top three are from on top of the sandstone mesa, about 400 feet high. The community has been occupied for several hundred years and remains so to this day.

Well, as seems to happen with some degree of regularity, City of Dust is going to go on hiatus. Someday my life may actually contain some semblance of stability and perhaps I’ll quit my ramblin’ ways, but ‘tis not now, apparently. This time it’s off to the desert, namely, New Mexico and Arizona. You know, many major figures throughout history have spent significant time in the desert. Moses. Jesus. Clint Eastwood. All these guys logged serious miles amongst the sand, the stones, and the snakes. Whether you’ve come to be tempted by Satan or have simply returned as a ghost to exact revenge on the town that did you wrong, the desert has the landscape, both physical and psychological, that you’ll need to get the job done. So, hey, I’m in good company.

How long will I be gone? Dunno. At least a couple weeks, so it’ll probably be late-November before another post appears. But it should be a good desert-themed one. I’m looking forward to taking lots of photos and will be armed with two cameras. Yes, two cameras! In the meantime, I’ve been posting photos on Flickr, all of which have appeared on City of Dust at some point, but Flickr is a nice way to get a few shots up elsewhere. Also, Phirebrush has a few photos and some scrawling of mine in their current issue (#32). Oh, and Snaps Magazine should have a photo or two as well in the Transportation and Weather issues. I'd heartily recommend these last two venues even if I wasn't a contributor.

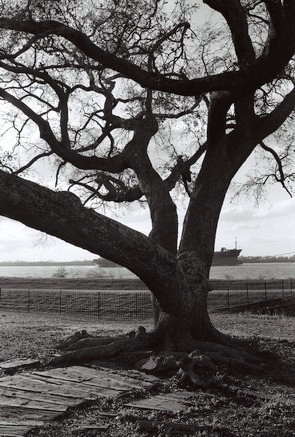

As for the photographs here, I thought one last look at water was appropriate. These were all shot with woefully expired film. The top photo was taken in Grand Marais, Minnesota, USA, with Kodak Gold that expired in 1996. The middle photograph, a mosquito-ridden lake in northern Wisconsin, and this last, Bayfield Harbor, Wisconsin, were shot with decade-old Seattle Filmworks film made out of old movie stock leftovers. Do you know how hard it is to find a place to process that stuff these days? Anyway, I find the idea of working hard to get an once-in-a-lifetime shot while never really being certain that your film is fit to be processed exhilarating. You can’t achieve that feeling with digital, can you? Nope, I thought not. Have a happy Halloween and I'll see you toward Thanksgiving.

"Happy is the city which in time of peace thinks of war." Ancient inscription in the armoury of the common-wealth of Venice, Italy.

"I wasn't always like this. You know, I had a home. A job. A wife and kids. But right now, right here, that doesn't just seem like a lifetime ago, it seems like those things belonged to another person. I feel no greater connection to my memories than if I'd found a box of polaroids on the ground and glimpsed the random moments of another man's life. No, those things happened to somebody I don't know and I'm somebody else. Someone bad." Rod Stevens, Venice, California.

"I wasn't always like this. You know, I had a home. A job. A wife and kids. But right now, right here, that doesn't just seem like a lifetime ago, it seems like those things belonged to another person. I feel no greater connection to my memories than if I'd found a box of polaroids on the ground and glimpsed the random moments of another man's life. No, those things happened to somebody I don't know and I'm somebody else. Someone bad." Rod Stevens, Venice, California.

"Hear, O ye Venetians, and I will tell you which is the best thing in the world: to contemn it." Inscription on the tomb of Sebastian Foscarinus, sometime Duke of Venice, Italy.

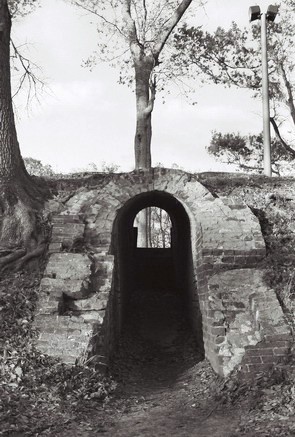

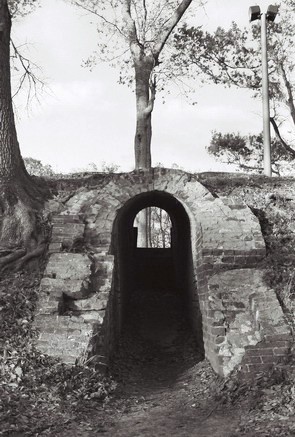

I managed to scrounge up enough material on Fort Jackson, an important Civil War fortress 65 miles south of New Orleans, to actually do a post with some historical content. Remember when I used to do such posts regularly? Well, don’t get your hopes up ‘cause this will probably be just a one-off for the time being. Anyway, Fort Jackson is way down the Louisiana Delta, on the west bank of the Mississippi River, near the present-day town of Triumph, a bit north of Venice, LA. After Katrina I don’t know how much of this area remains. I imagine it got hammered badly. On the other hand, the fort was mostly bricks and low earthworks, so if it didn’t get completely washed out into the Gulf of Mexico it might still look pretty much as it did when I took these photos on the day after Easter, 2005.

Fort Jackson was the brainchild of namesake Andrew Jackson, who recommended to then-Secretary of War John C. Calhoun that a fort be built at the mouth of the Mississippi to keep out the Spanish. General Jackson was considered to be a military hero following the Battle of New Orleans in 1815 (yes, THAT battle, three years AFTER the War of 1812), so the U.S. Government listened to him. Fortifications had been on the site as early as 1746 and Fort Bourbon erected in the 1790’s. Promptly destroyed by a hurricane in 1795, Fort Bourbon was quickly rebuilt before slipping silently into obscurity. Construction on Fort Jackson was begun in 1822 and the fort finally occupied in 1832. Built in the shape of a pentagon, the red brick walls are 20 feet thick and the entire structure surrounded by a moat. The foundation is made of cypress logs laid so as to level the fort in the swampy ground.

In the 1840’s it had been thought that Fort Jackson might be an important stronghold in the Mexican War, but it wasn't. Jackson was then of only minor importance until the Civil War, when Louisiana seized the site for the Confederacy on January 8, 1861. The people of New Orleans felt safe knowing that Fort Jackson (and its sister fort, St. Philip, just to the east, on the other side of the river) were protecting them from the Union. Further, the mouth of the river had been obstructed with the wrecks of old ships and a heavy chain run from bank-to-bank. Yup, nothing like a big ol' chain to stop a boat. The Daily Picayune of New Orleans wrote:  "By land we are impregnable and the coast and river's assailable points are susceptible to a degree of defense that floating wood or iron cannot make an impression." Well, that wasn’t quite right because on April 18, 1862 USN Commander David D. Porter's armada began shelling Fort Jackson. The barrage continued all night and one of Porter’s schooners was sunk. However, USN Flag Officer David G. Farragut's Western Gulf Blockading Squadron had been standing by and on April 20th breached Fort Jackson’s outer obstructions. Yet it took until the early morning of April 24th for Farragut’s ships to move past the two forts and fully engage the Confederate flotilla, eventually sinking or capturing thirteen vessels and breaking the back of the Confederacy’s naval presence on the Mississippi. The unhappy soldiers at Fort Jackson mutinied on April 27th and half the men left their posts. On April 28th, Confederate soldiers blew up their prized ironclad ship, aptly named the Louisiana, before CS Brigadier General Johnson K. Duncan surrendered both Forts Jackson and St. Philip to Commander Porter. Two-hundred and twenty-nine Union soldiers died in the battle along with 782 Confederates.

"By land we are impregnable and the coast and river's assailable points are susceptible to a degree of defense that floating wood or iron cannot make an impression." Well, that wasn’t quite right because on April 18, 1862 USN Commander David D. Porter's armada began shelling Fort Jackson. The barrage continued all night and one of Porter’s schooners was sunk. However, USN Flag Officer David G. Farragut's Western Gulf Blockading Squadron had been standing by and on April 20th breached Fort Jackson’s outer obstructions. Yet it took until the early morning of April 24th for Farragut’s ships to move past the two forts and fully engage the Confederate flotilla, eventually sinking or capturing thirteen vessels and breaking the back of the Confederacy’s naval presence on the Mississippi. The unhappy soldiers at Fort Jackson mutinied on April 27th and half the men left their posts. On April 28th, Confederate soldiers blew up their prized ironclad ship, aptly named the Louisiana, before CS Brigadier General Johnson K. Duncan surrendered both Forts Jackson and St. Philip to Commander Porter. Two-hundred and twenty-nine Union soldiers died in the battle along with 782 Confederates.

Following the Civil War, Fort Jackson became a prison and later a military training base. Thereafter, it was basically abandoned until 1898 when the threat of the Spanish-American war brought about a restoration and the addition of two large coastal guns. Fort Jackson became a training base once again in 1917-1918, during WWI, but afterward both it and Fort St. Philip were sold as surplus government property. Mr. and Mrs. H. J. Harvey of New Orleans bought Fort Jackson in 1927 and,in 1960, donated it to the Parish of Plaquemines for the purpose of restoring the fort and 82 acres of grounds. Jackson and St. Philip were immediately classified as National Historic Monuments, though Jackson was then called, “a veritable jungle with mud-filled tunnels infested with snakes.” Thus, levees were built to hold the river back and an automatic pumping station installed to keep the fort dry. Now, of course, one can’t help but wonder how those levees and pumps held up during Hurricane Katrina and what, if anything, might be left of old Fort Jackson. Anybody know? As for St. Philip, it's still privately owned, in bad repair, and was reportedly accessible only by boat BEFORE Katrina. It's probably gone now.

Following the Civil War, Fort Jackson became a prison and later a military training base. Thereafter, it was basically abandoned until 1898 when the threat of the Spanish-American war brought about a restoration and the addition of two large coastal guns. Fort Jackson became a training base once again in 1917-1918, during WWI, but afterward both it and Fort St. Philip were sold as surplus government property. Mr. and Mrs. H. J. Harvey of New Orleans bought Fort Jackson in 1927 and,in 1960, donated it to the Parish of Plaquemines for the purpose of restoring the fort and 82 acres of grounds. Jackson and St. Philip were immediately classified as National Historic Monuments, though Jackson was then called, “a veritable jungle with mud-filled tunnels infested with snakes.” Thus, levees were built to hold the river back and an automatic pumping station installed to keep the fort dry. Now, of course, one can’t help but wonder how those levees and pumps held up during Hurricane Katrina and what, if anything, might be left of old Fort Jackson. Anybody know? As for St. Philip, it's still privately owned, in bad repair, and was reportedly accessible only by boat BEFORE Katrina. It's probably gone now.

Thanks to Houghton Mifflin for info on the battle of Forts Jackson and St. Phillip and Civil War Album for historical detail on the life of Fort Jackson. Civil War Album notes that their information is courtesy of “the Fort Jackson tour guide” but whether this was a book or person I do not know.

South of the Twin Cities, in Hastings, Minnesota, USA, not far from the Mississippi River, is this dry prairie, or sand coulee, if you want to get technical. This was my workplace for the second half of September and all these photos were taken on the clock. Ha! For days on end we waded through a sea of big bluestem, little bluestem, and indian grass collecting native seeds.  This was certainly a good place for such work. Still, if you spend eight hours a day working someplace you inevitably find yourself looking forward to leaving when five o'clock rolls around. These shots are to remind me that there are many, many worse places to find oneself toiling. Anyway, the top shot is the hill we climbed up and down all day, the middle photo is the path we walked every morning, noon, and evening to get to and from the site, and at the bottom is some nice, tall big bluestem (AKA Andropogon gerardii). While quiet, sterile subdivisions ring the prairie on every side, this place is safe from development. I hope.

This was certainly a good place for such work. Still, if you spend eight hours a day working someplace you inevitably find yourself looking forward to leaving when five o'clock rolls around. These shots are to remind me that there are many, many worse places to find oneself toiling. Anyway, the top shot is the hill we climbed up and down all day, the middle photo is the path we walked every morning, noon, and evening to get to and from the site, and at the bottom is some nice, tall big bluestem (AKA Andropogon gerardii). While quiet, sterile subdivisions ring the prairie on every side, this place is safe from development. I hope.

Canal Park/Lake Superior, Duluth, Minnesota, USA; August 28, 2005; Afternoon.

Mouth of Brule River/Lake Superior, Wisconsin, USA; June 13, 2005; Afternoon.

Harbor/Lake Superior, Grand Marais, Minnesota, USA; September 8, 2005; Morning.

The couple next door—that’s room 6—is fighting again. I’ve been here two and a half weeks, three more days than they have, and have grown accustomed to these recurrent challenges to their connubial bliss. I’ve also become quite good at estimating their duration. So, I put down my notebook and head over to the Cenex gas station for the usual: an ice cream sandwich.

Outside, it’s dark and a cloud of insects surrounds each of the lights in the parking lot. In the distance, lightning flashes soundlessly. I walk across the street to the gas station, where groups of kids have gathered, some inside pick-up trucks, others just sitting on the curb. I pass two teenage boys and catch a bit of conversation. One boy says that “this guy” might have “some stuff” by tomorrow. The other kid replies that that’s not good enough, that he’s talked to a friend who knows someone that will have something by midnight and it should be down at the Cenex in a few hours. The boys are rail-thin, their t-shirts and ratty jeans hanging off their bones. One of them runs his hand over his face continually, another fidgets, kicking at stones as he talks. They both look flushed and damp, although the night is cool. I’m not surprised: meth is rampant around here, consuming the young, feeding off boredom and bravado.

I walk into the store and get my ice cream sandwich, then leave through the other door and head toward the highway. I stand on the gravel shoulder, eating, and there are no cars, only insects and the breeze off the prairie. Then there’s some more lightning on the horizon. Through the darkness I can see some ramshackle homes on the other side of the road. I can’t imagine that anyone lives in them. I smile at one thing: I don’t live in them either.

After finishing the ice cream I turn back toward the Cenex where, in the parking lot, a fight has broken out. One of the skinny kids I saw earlier, the one that couldn’t wait until tomorrow, is up against a big guy in a green cut-off t-shirt that reads “DEERE” in yellow ink. The skinny kid looks like he’s had his nose broken and blood covers the lower half of his face. Under the yellow lamps the blood looks like tar. Everyone that was in the lot earlier has circled these two and they’re shouting and clapping their hands. The woman from the counter is standing on the sidewalk. She’s yelling for everyone to leave, saying that she’s called the cops, that they’re on their way. No one pays her any attention. The skinny kid’s friend yells something in his ear that I can’t make out then gives him a pat on the shoulder. Suddenly the kid lunges for the big guy, flailing and swinging wildly. The big guy steps lightly to the left, as if in no real hurry, and punches the kid in the center of the face with two sharp shots. The crowd yells and claps their hands, everyone smiling or frowning or swearing. A couple people are holding wads of bills. The kid staggers backward but stays on his feet. Big drops of blood fall onto the gravel. His friend gives him another pat and the kid squares up again, fists up in front of his chest. I can’t help but admire him, this doomed teenager, for his tenacity, his refusal (or inability) to recognize physical pain, and his willingness to see a lost cause through to the bitter end simply because he can imagine no other option, even though he must know somewhere deep down that the price he’ll have to pay could be very high indeed. But I don’t really have the stomach for this and I turn back toward my room. Behind me I hear two more pulpy thuds and a louder chorus of cheers. The cashier starts yelling about the police again. I don’t turn around to see what’s happened.

Back in my room I can hear the woman next door sobbing, so I leave the light off. I just sit on the bed, looking out the window at the lightning now growing closer, wishing I could click my heels and be someplace else, someplace good. But I figure it’s been a long time since there was any place like home. After awhile I hear sirens over at the Cenex. The woman next door has quieted, so I get up off the bed, turn on the light, and get back to work.

She was wearing an old blue wool sweater her brother had given her for Christmas years ago and jeans. Her blonde hair was pulled tightly back away from her face in a style she usually only wore when cleaning the house or exercising. I wondered if there was some significance in her appearance. She seemed tired and this made her look a bit older than she was, her green eyes shining a little in the sunlight. For all that she looked beautiful, as I thought she always did. If only beauty were enough. I waited for her to say something, but she remained quiet.

She was wearing an old blue wool sweater her brother had given her for Christmas years ago and jeans. Her blonde hair was pulled tightly back away from her face in a style she usually only wore when cleaning the house or exercising. I wondered if there was some significance in her appearance. She seemed tired and this made her look a bit older than she was, her green eyes shining a little in the sunlight. For all that she looked beautiful, as I thought she always did. If only beauty were enough. I waited for her to say something, but she remained quiet.

Actually, it had taken more than just the advance, but at that time I‘d figured I’d made it, that the money would just keep rolling in. Of course, I’d been wrong. Yet I still loved the sleek and speedy reminder of my folly and now regretted not cleaning off the thick layer of desert dust that had accumulated over the last weeks. I ran a finger over the trunk and left a clean, black trail. I hesitated. It seemed I now suddenly had two reasons to stay in Santa Fe and just one to leave. I shook my head: that one reason alone was bigger than all the other reasons there could possibly be all put together. Suddenly I was very tired. I hoped I could sleep on the plane. I grabbed my bag and ran for the terminal. (

Actually, it had taken more than just the advance, but at that time I‘d figured I’d made it, that the money would just keep rolling in. Of course, I’d been wrong. Yet I still loved the sleek and speedy reminder of my folly and now regretted not cleaning off the thick layer of desert dust that had accumulated over the last weeks. I ran a finger over the trunk and left a clean, black trail. I hesitated. It seemed I now suddenly had two reasons to stay in Santa Fe and just one to leave. I shook my head: that one reason alone was bigger than all the other reasons there could possibly be all put together. Suddenly I was very tired. I hoped I could sleep on the plane. I grabbed my bag and ran for the terminal. (

A wire snaked from the back of the phone through the lot and up the stairs into the gutted building. I lifted the receiver off the cradle and heard a dial tone. I was instantly euphoric, a bubble of well-being rising from my stomach into my chest. But that joy disappeared just as quickly as I tried to recall what number I needed to dial. Again and again I punched numbers and again and again a woman’s voice, a robotic recording, told me that I was not allowed to contact this party, to please hang up and try another number. I tried the connection at the back of the phone and the wire broke off in my hand. The phone went dead. Just then a large man dressed in filthy rags began to stagger toward me, bellowing angrily, “Man, you better not have broken that phone! You better not!” Frantically, I tried to fix the phone as the man approached but I could not. I remember the fear, but that is all I remember. Then, nothing.

A wire snaked from the back of the phone through the lot and up the stairs into the gutted building. I lifted the receiver off the cradle and heard a dial tone. I was instantly euphoric, a bubble of well-being rising from my stomach into my chest. But that joy disappeared just as quickly as I tried to recall what number I needed to dial. Again and again I punched numbers and again and again a woman’s voice, a robotic recording, told me that I was not allowed to contact this party, to please hang up and try another number. I tried the connection at the back of the phone and the wire broke off in my hand. The phone went dead. Just then a large man dressed in filthy rags began to stagger toward me, bellowing angrily, “Man, you better not have broken that phone! You better not!” Frantically, I tried to fix the phone as the man approached but I could not. I remember the fear, but that is all I remember. Then, nothing.

I sat in a corner and watched the band, a pretty decent if glum-looking four-piece, who forsook all unnecessary stage banter as they moved woozily from one tune to the next. As the opening chords to "Galveston" rang out, I noticed three guys at a table on the far side of the dance floor. One of them had a patchy, unkempt beard and long, brown, stringy hair hanging down his shoulders. He was wearing what looked like a leather trench coat, similar to the kind ranchers might wear. Only, he was no cowboy. At the table with him were a skinny guy in a jean jacket and Pabst hat and another guy with long, brown hair and sunglasses perched on top of his head despite the sun having been down for hours. They were all probably in their late-twenties, although aging quickly and looking a little older than I guessed they really were. On the table were sixteen bottles of Lone Star, which I took the time to count twice.

I sat in a corner and watched the band, a pretty decent if glum-looking four-piece, who forsook all unnecessary stage banter as they moved woozily from one tune to the next. As the opening chords to "Galveston" rang out, I noticed three guys at a table on the far side of the dance floor. One of them had a patchy, unkempt beard and long, brown, stringy hair hanging down his shoulders. He was wearing what looked like a leather trench coat, similar to the kind ranchers might wear. Only, he was no cowboy. At the table with him were a skinny guy in a jean jacket and Pabst hat and another guy with long, brown hair and sunglasses perched on top of his head despite the sun having been down for hours. They were all probably in their late-twenties, although aging quickly and looking a little older than I guessed they really were. On the table were sixteen bottles of Lone Star, which I took the time to count twice.

The man notices this, closes his eyes tightly, as if it was difficult, then opens them and screams, “Collie! Collie! Collie!” The restaurant goes dead quiet. Everyone turns to look. Seconds pass. Waffles begin to burn. Hashbrowns go unsmothered and uncovered. “Collie!” he screams again and, with his balled right hand, begins to punch himself in the face. Four, five, six times the man strikes himself, in the cheek, the mouth, the eye. Finally, he pulls his fist back one last time but, instead of hitting himself, he throws a handful of change at the counter. Coins explode through the kitchen and dining area, so many that he must’ve been intending to pay mostly in pennies. In tears, the man points to a mug and says, “Cobby!” The waitress is stunned. “Coffee?” she whispers. Tears flow down the man’s face. Thick red welts have risen on his forehead. “Yuh!” he yells, but turns to leave the restaurant. As he exits the door he punches the frame and screams again, then runs across the parking lot, around a truck, and out of view.

The man notices this, closes his eyes tightly, as if it was difficult, then opens them and screams, “Collie! Collie! Collie!” The restaurant goes dead quiet. Everyone turns to look. Seconds pass. Waffles begin to burn. Hashbrowns go unsmothered and uncovered. “Collie!” he screams again and, with his balled right hand, begins to punch himself in the face. Four, five, six times the man strikes himself, in the cheek, the mouth, the eye. Finally, he pulls his fist back one last time but, instead of hitting himself, he throws a handful of change at the counter. Coins explode through the kitchen and dining area, so many that he must’ve been intending to pay mostly in pennies. In tears, the man points to a mug and says, “Cobby!” The waitress is stunned. “Coffee?” she whispers. Tears flow down the man’s face. Thick red welts have risen on his forehead. “Yuh!” he yells, but turns to leave the restaurant. As he exits the door he punches the frame and screams again, then runs across the parking lot, around a truck, and out of view.

"I wasn't always like this. You know, I had a home. A job. A wife and kids. But right now, right here, that doesn't just seem like a lifetime ago, it seems like those things belonged to another person. I feel no greater connection to my memories than if I'd found a box of polaroids on the ground and glimpsed the random moments of another man's life. No, those things happened to somebody I don't know and I'm somebody else. Someone bad." Rod Stevens, Venice, California.

"I wasn't always like this. You know, I had a home. A job. A wife and kids. But right now, right here, that doesn't just seem like a lifetime ago, it seems like those things belonged to another person. I feel no greater connection to my memories than if I'd found a box of polaroids on the ground and glimpsed the random moments of another man's life. No, those things happened to somebody I don't know and I'm somebody else. Someone bad." Rod Stevens, Venice, California.

"By land we are impregnable and the coast and river's assailable points are susceptible to a degree of defense that floating wood or iron cannot make an impression." Well, that wasn’t quite right because on April 18, 1862 USN Commander David D. Porter's armada began shelling Fort Jackson. The barrage continued all night and one of Porter’s schooners was sunk. However, USN Flag Officer David G. Farragut's Western Gulf Blockading Squadron had been standing by and on April 20th breached Fort Jackson’s outer obstructions. Yet it took until the early morning of April 24th for Farragut’s ships to move past the two forts and fully engage the Confederate flotilla, eventually sinking or capturing thirteen vessels and breaking the back of the Confederacy’s naval presence on the Mississippi. The unhappy soldiers at Fort Jackson mutinied on April 27th and half the men left their posts. On April 28th, Confederate soldiers blew up their prized ironclad ship, aptly named the Louisiana, before CS Brigadier General Johnson K. Duncan surrendered both Forts Jackson and St. Philip to Commander Porter. Two-hundred and twenty-nine Union soldiers died in the battle along with 782 Confederates.

"By land we are impregnable and the coast and river's assailable points are susceptible to a degree of defense that floating wood or iron cannot make an impression." Well, that wasn’t quite right because on April 18, 1862 USN Commander David D. Porter's armada began shelling Fort Jackson. The barrage continued all night and one of Porter’s schooners was sunk. However, USN Flag Officer David G. Farragut's Western Gulf Blockading Squadron had been standing by and on April 20th breached Fort Jackson’s outer obstructions. Yet it took until the early morning of April 24th for Farragut’s ships to move past the two forts and fully engage the Confederate flotilla, eventually sinking or capturing thirteen vessels and breaking the back of the Confederacy’s naval presence on the Mississippi. The unhappy soldiers at Fort Jackson mutinied on April 27th and half the men left their posts. On April 28th, Confederate soldiers blew up their prized ironclad ship, aptly named the Louisiana, before CS Brigadier General Johnson K. Duncan surrendered both Forts Jackson and St. Philip to Commander Porter. Two-hundred and twenty-nine Union soldiers died in the battle along with 782 Confederates.  Following the Civil War, Fort Jackson became a prison and later a military training base. Thereafter, it was basically abandoned until 1898 when the threat of the Spanish-American war brought about a restoration and the addition of two large coastal guns. Fort Jackson became a training base once again in 1917-1918, during WWI, but afterward both it and Fort St. Philip were sold as surplus government property. Mr. and Mrs. H. J. Harvey of New Orleans bought Fort Jackson in 1927 and,in 1960, donated it to the Parish of Plaquemines for the purpose of restoring the fort and 82 acres of grounds. Jackson and St. Philip were immediately classified as National Historic Monuments, though Jackson was then called, “a veritable jungle with mud-filled tunnels infested with snakes.” Thus, levees were built to hold the river back and an automatic pumping station installed to keep the fort dry. Now, of course, one can’t help but wonder how those levees and pumps held up during Hurricane Katrina and what, if anything, might be left of old Fort Jackson. Anybody know? As for St. Philip, it's still privately owned, in bad repair, and was reportedly accessible only by boat BEFORE Katrina. It's probably gone now.

Following the Civil War, Fort Jackson became a prison and later a military training base. Thereafter, it was basically abandoned until 1898 when the threat of the Spanish-American war brought about a restoration and the addition of two large coastal guns. Fort Jackson became a training base once again in 1917-1918, during WWI, but afterward both it and Fort St. Philip were sold as surplus government property. Mr. and Mrs. H. J. Harvey of New Orleans bought Fort Jackson in 1927 and,in 1960, donated it to the Parish of Plaquemines for the purpose of restoring the fort and 82 acres of grounds. Jackson and St. Philip were immediately classified as National Historic Monuments, though Jackson was then called, “a veritable jungle with mud-filled tunnels infested with snakes.” Thus, levees were built to hold the river back and an automatic pumping station installed to keep the fort dry. Now, of course, one can’t help but wonder how those levees and pumps held up during Hurricane Katrina and what, if anything, might be left of old Fort Jackson. Anybody know? As for St. Philip, it's still privately owned, in bad repair, and was reportedly accessible only by boat BEFORE Katrina. It's probably gone now.

This night is unwelcome. The wind has risen, the sun has set too soon. Beyond the window, black birds are gathering in the tree tops. The birds speak to you; you try to believe you don’t understand what they are saying. Would that you could sleep. To awake on the other side, the danger passed, was once easy. The dawn arose clean and forgetful. But now there comes a knock at the door that you need not answer, for he will show himself in.

This night is unwelcome. The wind has risen, the sun has set too soon. Beyond the window, black birds are gathering in the tree tops. The birds speak to you; you try to believe you don’t understand what they are saying. Would that you could sleep. To awake on the other side, the danger passed, was once easy. The dawn arose clean and forgetful. But now there comes a knock at the door that you need not answer, for he will show himself in.

This was certainly a good place for such work. Still, if you spend eight hours a day working someplace you inevitably find yourself looking forward to leaving when five o'clock rolls around. These shots are to remind me that there are many, many worse places to find oneself toiling. Anyway, the top shot is the hill we climbed up and down all day, the middle photo is the path we walked every morning, noon, and evening to get to and from the site, and at the bottom is some nice, tall big bluestem (AKA Andropogon gerardii). While quiet, sterile subdivisions ring the prairie on every side, this place is safe from development. I hope.

This was certainly a good place for such work. Still, if you spend eight hours a day working someplace you inevitably find yourself looking forward to leaving when five o'clock rolls around. These shots are to remind me that there are many, many worse places to find oneself toiling. Anyway, the top shot is the hill we climbed up and down all day, the middle photo is the path we walked every morning, noon, and evening to get to and from the site, and at the bottom is some nice, tall big bluestem (AKA Andropogon gerardii). While quiet, sterile subdivisions ring the prairie on every side, this place is safe from development. I hope.