skip to main |

skip to sidebar

Well, as seems to happen with some degree of regularity, City of Dust is going to go on hiatus. Someday my life may actually contain some semblance of stability and perhaps I’ll quit my ramblin’ ways, but ‘tis not now, apparently. This time it’s off to the desert, namely, New Mexico and Arizona. You know, many major figures throughout history have spent significant time in the desert. Moses. Jesus. Clint Eastwood. All these guys logged serious miles amongst the sand, the stones, and the snakes. Whether you’ve come to be tempted by Satan or have simply returned as a ghost to exact revenge on the town that did you wrong, the desert has the landscape, both physical and psychological, that you’ll need to get the job done. So, hey, I’m in good company.

How long will I be gone? Dunno. At least a couple weeks, so it’ll probably be late-November before another post appears. But it should be a good desert-themed one. I’m looking forward to taking lots of photos and will be armed with two cameras. Yes, two cameras! In the meantime, I’ve been posting photos on Flickr, all of which have appeared on City of Dust at some point, but Flickr is a nice way to get a few shots up elsewhere. Also, Phirebrush has a few photos and some scrawling of mine in their current issue (#32). Oh, and Snaps Magazine should have a photo or two as well in the Transportation and Weather issues. I'd heartily recommend these last two venues even if I wasn't a contributor.

As for the photographs here, I thought one last look at water was appropriate. These were all shot with woefully expired film. The top photo was taken in Grand Marais, Minnesota, USA, with Kodak Gold that expired in 1996. The middle photograph, a mosquito-ridden lake in northern Wisconsin, and this last, Bayfield Harbor, Wisconsin, were shot with decade-old Seattle Filmworks film made out of old movie stock leftovers. Do you know how hard it is to find a place to process that stuff these days? Anyway, I find the idea of working hard to get an once-in-a-lifetime shot while never really being certain that your film is fit to be processed exhilarating. You can’t achieve that feeling with digital, can you? Nope, I thought not. Have a happy Halloween and I'll see you toward Thanksgiving.

"Happy is the city which in time of peace thinks of war." Ancient inscription in the armoury of the common-wealth of Venice, Italy.

"I wasn't always like this. You know, I had a home. A job. A wife and kids. But right now, right here, that doesn't just seem like a lifetime ago, it seems like those things belonged to another person. I feel no greater connection to my memories than if I'd found a box of polaroids on the ground and glimpsed the random moments of another man's life. No, those things happened to somebody I don't know and I'm somebody else. Someone bad." Rod Stevens, Venice, California.

"I wasn't always like this. You know, I had a home. A job. A wife and kids. But right now, right here, that doesn't just seem like a lifetime ago, it seems like those things belonged to another person. I feel no greater connection to my memories than if I'd found a box of polaroids on the ground and glimpsed the random moments of another man's life. No, those things happened to somebody I don't know and I'm somebody else. Someone bad." Rod Stevens, Venice, California.

"Hear, O ye Venetians, and I will tell you which is the best thing in the world: to contemn it." Inscription on the tomb of Sebastian Foscarinus, sometime Duke of Venice, Italy.

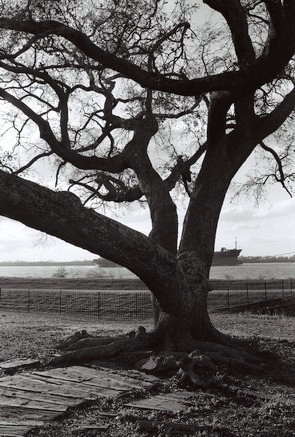

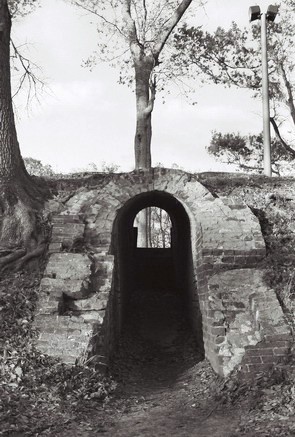

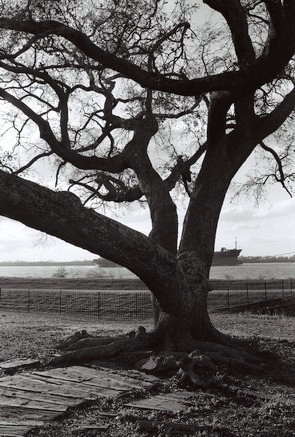

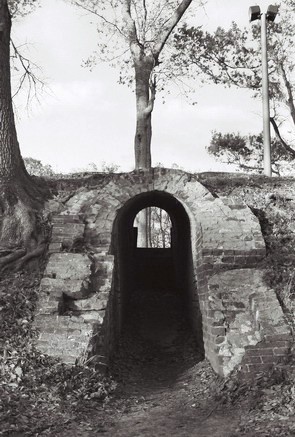

I managed to scrounge up enough material on Fort Jackson, an important Civil War fortress 65 miles south of New Orleans, to actually do a post with some historical content. Remember when I used to do such posts regularly? Well, don’t get your hopes up ‘cause this will probably be just a one-off for the time being. Anyway, Fort Jackson is way down the Louisiana Delta, on the west bank of the Mississippi River, near the present-day town of Triumph, a bit north of Venice, LA. After Katrina I don’t know how much of this area remains. I imagine it got hammered badly. On the other hand, the fort was mostly bricks and low earthworks, so if it didn’t get completely washed out into the Gulf of Mexico it might still look pretty much as it did when I took these photos on the day after Easter, 2005.

Fort Jackson was the brainchild of namesake Andrew Jackson, who recommended to then-Secretary of War John C. Calhoun that a fort be built at the mouth of the Mississippi to keep out the Spanish. General Jackson was considered to be a military hero following the Battle of New Orleans in 1815 (yes, THAT battle, three years AFTER the War of 1812), so the U.S. Government listened to him. Fortifications had been on the site as early as 1746 and Fort Bourbon erected in the 1790’s. Promptly destroyed by a hurricane in 1795, Fort Bourbon was quickly rebuilt before slipping silently into obscurity. Construction on Fort Jackson was begun in 1822 and the fort finally occupied in 1832. Built in the shape of a pentagon, the red brick walls are 20 feet thick and the entire structure surrounded by a moat. The foundation is made of cypress logs laid so as to level the fort in the swampy ground.

In the 1840’s it had been thought that Fort Jackson might be an important stronghold in the Mexican War, but it wasn't. Jackson was then of only minor importance until the Civil War, when Louisiana seized the site for the Confederacy on January 8, 1861. The people of New Orleans felt safe knowing that Fort Jackson (and its sister fort, St. Philip, just to the east, on the other side of the river) were protecting them from the Union. Further, the mouth of the river had been obstructed with the wrecks of old ships and a heavy chain run from bank-to-bank. Yup, nothing like a big ol' chain to stop a boat. The Daily Picayune of New Orleans wrote:  "By land we are impregnable and the coast and river's assailable points are susceptible to a degree of defense that floating wood or iron cannot make an impression." Well, that wasn’t quite right because on April 18, 1862 USN Commander David D. Porter's armada began shelling Fort Jackson. The barrage continued all night and one of Porter’s schooners was sunk. However, USN Flag Officer David G. Farragut's Western Gulf Blockading Squadron had been standing by and on April 20th breached Fort Jackson’s outer obstructions. Yet it took until the early morning of April 24th for Farragut’s ships to move past the two forts and fully engage the Confederate flotilla, eventually sinking or capturing thirteen vessels and breaking the back of the Confederacy’s naval presence on the Mississippi. The unhappy soldiers at Fort Jackson mutinied on April 27th and half the men left their posts. On April 28th, Confederate soldiers blew up their prized ironclad ship, aptly named the Louisiana, before CS Brigadier General Johnson K. Duncan surrendered both Forts Jackson and St. Philip to Commander Porter. Two-hundred and twenty-nine Union soldiers died in the battle along with 782 Confederates.

"By land we are impregnable and the coast and river's assailable points are susceptible to a degree of defense that floating wood or iron cannot make an impression." Well, that wasn’t quite right because on April 18, 1862 USN Commander David D. Porter's armada began shelling Fort Jackson. The barrage continued all night and one of Porter’s schooners was sunk. However, USN Flag Officer David G. Farragut's Western Gulf Blockading Squadron had been standing by and on April 20th breached Fort Jackson’s outer obstructions. Yet it took until the early morning of April 24th for Farragut’s ships to move past the two forts and fully engage the Confederate flotilla, eventually sinking or capturing thirteen vessels and breaking the back of the Confederacy’s naval presence on the Mississippi. The unhappy soldiers at Fort Jackson mutinied on April 27th and half the men left their posts. On April 28th, Confederate soldiers blew up their prized ironclad ship, aptly named the Louisiana, before CS Brigadier General Johnson K. Duncan surrendered both Forts Jackson and St. Philip to Commander Porter. Two-hundred and twenty-nine Union soldiers died in the battle along with 782 Confederates.

Following the Civil War, Fort Jackson became a prison and later a military training base. Thereafter, it was basically abandoned until 1898 when the threat of the Spanish-American war brought about a restoration and the addition of two large coastal guns. Fort Jackson became a training base once again in 1917-1918, during WWI, but afterward both it and Fort St. Philip were sold as surplus government property. Mr. and Mrs. H. J. Harvey of New Orleans bought Fort Jackson in 1927 and,in 1960, donated it to the Parish of Plaquemines for the purpose of restoring the fort and 82 acres of grounds. Jackson and St. Philip were immediately classified as National Historic Monuments, though Jackson was then called, “a veritable jungle with mud-filled tunnels infested with snakes.” Thus, levees were built to hold the river back and an automatic pumping station installed to keep the fort dry. Now, of course, one can’t help but wonder how those levees and pumps held up during Hurricane Katrina and what, if anything, might be left of old Fort Jackson. Anybody know? As for St. Philip, it's still privately owned, in bad repair, and was reportedly accessible only by boat BEFORE Katrina. It's probably gone now.

Following the Civil War, Fort Jackson became a prison and later a military training base. Thereafter, it was basically abandoned until 1898 when the threat of the Spanish-American war brought about a restoration and the addition of two large coastal guns. Fort Jackson became a training base once again in 1917-1918, during WWI, but afterward both it and Fort St. Philip were sold as surplus government property. Mr. and Mrs. H. J. Harvey of New Orleans bought Fort Jackson in 1927 and,in 1960, donated it to the Parish of Plaquemines for the purpose of restoring the fort and 82 acres of grounds. Jackson and St. Philip were immediately classified as National Historic Monuments, though Jackson was then called, “a veritable jungle with mud-filled tunnels infested with snakes.” Thus, levees were built to hold the river back and an automatic pumping station installed to keep the fort dry. Now, of course, one can’t help but wonder how those levees and pumps held up during Hurricane Katrina and what, if anything, might be left of old Fort Jackson. Anybody know? As for St. Philip, it's still privately owned, in bad repair, and was reportedly accessible only by boat BEFORE Katrina. It's probably gone now.

Thanks to Houghton Mifflin for info on the battle of Forts Jackson and St. Phillip and Civil War Album for historical detail on the life of Fort Jackson. Civil War Album notes that their information is courtesy of “the Fort Jackson tour guide” but whether this was a book or person I do not know.

South of the Twin Cities, in Hastings, Minnesota, USA, not far from the Mississippi River, is this dry prairie, or sand coulee, if you want to get technical. This was my workplace for the second half of September and all these photos were taken on the clock. Ha! For days on end we waded through a sea of big bluestem, little bluestem, and indian grass collecting native seeds.  This was certainly a good place for such work. Still, if you spend eight hours a day working someplace you inevitably find yourself looking forward to leaving when five o'clock rolls around. These shots are to remind me that there are many, many worse places to find oneself toiling. Anyway, the top shot is the hill we climbed up and down all day, the middle photo is the path we walked every morning, noon, and evening to get to and from the site, and at the bottom is some nice, tall big bluestem (AKA Andropogon gerardii). While quiet, sterile subdivisions ring the prairie on every side, this place is safe from development. I hope.

This was certainly a good place for such work. Still, if you spend eight hours a day working someplace you inevitably find yourself looking forward to leaving when five o'clock rolls around. These shots are to remind me that there are many, many worse places to find oneself toiling. Anyway, the top shot is the hill we climbed up and down all day, the middle photo is the path we walked every morning, noon, and evening to get to and from the site, and at the bottom is some nice, tall big bluestem (AKA Andropogon gerardii). While quiet, sterile subdivisions ring the prairie on every side, this place is safe from development. I hope.

"I wasn't always like this. You know, I had a home. A job. A wife and kids. But right now, right here, that doesn't just seem like a lifetime ago, it seems like those things belonged to another person. I feel no greater connection to my memories than if I'd found a box of polaroids on the ground and glimpsed the random moments of another man's life. No, those things happened to somebody I don't know and I'm somebody else. Someone bad." Rod Stevens, Venice, California.

"I wasn't always like this. You know, I had a home. A job. A wife and kids. But right now, right here, that doesn't just seem like a lifetime ago, it seems like those things belonged to another person. I feel no greater connection to my memories than if I'd found a box of polaroids on the ground and glimpsed the random moments of another man's life. No, those things happened to somebody I don't know and I'm somebody else. Someone bad." Rod Stevens, Venice, California.

"By land we are impregnable and the coast and river's assailable points are susceptible to a degree of defense that floating wood or iron cannot make an impression." Well, that wasn’t quite right because on April 18, 1862 USN Commander David D. Porter's armada began shelling Fort Jackson. The barrage continued all night and one of Porter’s schooners was sunk. However, USN Flag Officer David G. Farragut's Western Gulf Blockading Squadron had been standing by and on April 20th breached Fort Jackson’s outer obstructions. Yet it took until the early morning of April 24th for Farragut’s ships to move past the two forts and fully engage the Confederate flotilla, eventually sinking or capturing thirteen vessels and breaking the back of the Confederacy’s naval presence on the Mississippi. The unhappy soldiers at Fort Jackson mutinied on April 27th and half the men left their posts. On April 28th, Confederate soldiers blew up their prized ironclad ship, aptly named the Louisiana, before CS Brigadier General Johnson K. Duncan surrendered both Forts Jackson and St. Philip to Commander Porter. Two-hundred and twenty-nine Union soldiers died in the battle along with 782 Confederates.

"By land we are impregnable and the coast and river's assailable points are susceptible to a degree of defense that floating wood or iron cannot make an impression." Well, that wasn’t quite right because on April 18, 1862 USN Commander David D. Porter's armada began shelling Fort Jackson. The barrage continued all night and one of Porter’s schooners was sunk. However, USN Flag Officer David G. Farragut's Western Gulf Blockading Squadron had been standing by and on April 20th breached Fort Jackson’s outer obstructions. Yet it took until the early morning of April 24th for Farragut’s ships to move past the two forts and fully engage the Confederate flotilla, eventually sinking or capturing thirteen vessels and breaking the back of the Confederacy’s naval presence on the Mississippi. The unhappy soldiers at Fort Jackson mutinied on April 27th and half the men left their posts. On April 28th, Confederate soldiers blew up their prized ironclad ship, aptly named the Louisiana, before CS Brigadier General Johnson K. Duncan surrendered both Forts Jackson and St. Philip to Commander Porter. Two-hundred and twenty-nine Union soldiers died in the battle along with 782 Confederates.  Following the Civil War, Fort Jackson became a prison and later a military training base. Thereafter, it was basically abandoned until 1898 when the threat of the Spanish-American war brought about a restoration and the addition of two large coastal guns. Fort Jackson became a training base once again in 1917-1918, during WWI, but afterward both it and Fort St. Philip were sold as surplus government property. Mr. and Mrs. H. J. Harvey of New Orleans bought Fort Jackson in 1927 and,in 1960, donated it to the Parish of Plaquemines for the purpose of restoring the fort and 82 acres of grounds. Jackson and St. Philip were immediately classified as National Historic Monuments, though Jackson was then called, “a veritable jungle with mud-filled tunnels infested with snakes.” Thus, levees were built to hold the river back and an automatic pumping station installed to keep the fort dry. Now, of course, one can’t help but wonder how those levees and pumps held up during Hurricane Katrina and what, if anything, might be left of old Fort Jackson. Anybody know? As for St. Philip, it's still privately owned, in bad repair, and was reportedly accessible only by boat BEFORE Katrina. It's probably gone now.

Following the Civil War, Fort Jackson became a prison and later a military training base. Thereafter, it was basically abandoned until 1898 when the threat of the Spanish-American war brought about a restoration and the addition of two large coastal guns. Fort Jackson became a training base once again in 1917-1918, during WWI, but afterward both it and Fort St. Philip were sold as surplus government property. Mr. and Mrs. H. J. Harvey of New Orleans bought Fort Jackson in 1927 and,in 1960, donated it to the Parish of Plaquemines for the purpose of restoring the fort and 82 acres of grounds. Jackson and St. Philip were immediately classified as National Historic Monuments, though Jackson was then called, “a veritable jungle with mud-filled tunnels infested with snakes.” Thus, levees were built to hold the river back and an automatic pumping station installed to keep the fort dry. Now, of course, one can’t help but wonder how those levees and pumps held up during Hurricane Katrina and what, if anything, might be left of old Fort Jackson. Anybody know? As for St. Philip, it's still privately owned, in bad repair, and was reportedly accessible only by boat BEFORE Katrina. It's probably gone now.

This night is unwelcome. The wind has risen, the sun has set too soon. Beyond the window, black birds are gathering in the tree tops. The birds speak to you; you try to believe you don’t understand what they are saying. Would that you could sleep. To awake on the other side, the danger passed, was once easy. The dawn arose clean and forgetful. But now there comes a knock at the door that you need not answer, for he will show himself in.

This night is unwelcome. The wind has risen, the sun has set too soon. Beyond the window, black birds are gathering in the tree tops. The birds speak to you; you try to believe you don’t understand what they are saying. Would that you could sleep. To awake on the other side, the danger passed, was once easy. The dawn arose clean and forgetful. But now there comes a knock at the door that you need not answer, for he will show himself in.

This was certainly a good place for such work. Still, if you spend eight hours a day working someplace you inevitably find yourself looking forward to leaving when five o'clock rolls around. These shots are to remind me that there are many, many worse places to find oneself toiling. Anyway, the top shot is the hill we climbed up and down all day, the middle photo is the path we walked every morning, noon, and evening to get to and from the site, and at the bottom is some nice, tall big bluestem (AKA Andropogon gerardii). While quiet, sterile subdivisions ring the prairie on every side, this place is safe from development. I hope.

This was certainly a good place for such work. Still, if you spend eight hours a day working someplace you inevitably find yourself looking forward to leaving when five o'clock rolls around. These shots are to remind me that there are many, many worse places to find oneself toiling. Anyway, the top shot is the hill we climbed up and down all day, the middle photo is the path we walked every morning, noon, and evening to get to and from the site, and at the bottom is some nice, tall big bluestem (AKA Andropogon gerardii). While quiet, sterile subdivisions ring the prairie on every side, this place is safe from development. I hope.