skip to main |

skip to sidebar

“Photographers deal in things which are continually vanishing and when they have vanished there is no contrivance on earth which can make them come back again.” Henri Cartier-Bresson.

You know, it’s hard to argue with Cartier-Bresson. But perhaps that’s because what he said is simply a truism. It’s not just photographers that deal with things that are continually vanishing, but every human being every second of the day. You want your grandparents back? Nope. Your high school girlfriend? Gone. How about today’s lunch? No dice. Unless, of course, you had the foresight to take a picture of it with your phone and post it on Facebook. Then you, too, can feel like an artist on par with Cartier-Bresson. You know, sometimes this art gets a little high-falutin’ for me.

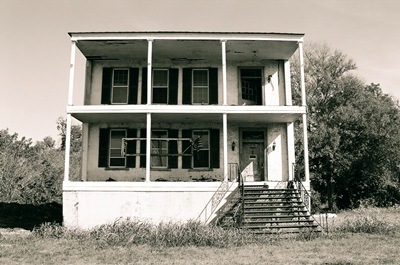

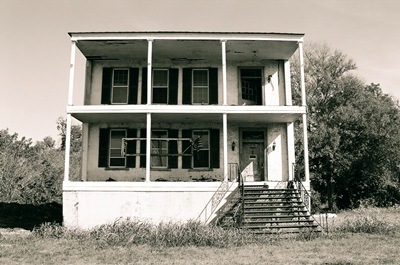

So, with that out of the way, let’s make a stop at the former house of the Reverend Charles T. Walker, 1011 Laney-Walker Boulevard, Augusta, GA. The Reverend has vanished, but the impact of his work remains. As does his church. And his house. But while the former is doing fine, the latter is in some trouble.

Reverend Walker was born into slavery near Hephzibah, GA in 1858. An orphan by the age of 8, he found Jesus while hoeing cotton and would later eat only two meals a day to pay for his studies at the Augusta Theological Institute.

On August 21, 1885, Walker was the driving force in establishing the Beulah Baptist Church in Augusta. Three days later he asked that the name be changed to Tabernacle Baptist Church. And so it was. The first congregation numbered 310. By 1889, membership was at 2,000, largely thanks to Walker’s sermonizing. People began to call him the “Black Spurgeon,” a reference to British Baptist minister Charles Spurgeon, then known as the “Prince of Preachers.” Indeed, Spurgeon invited Walker to give a sermon in London, where it was said Walker enraptured the crowd with his fiery and erudite style. So, Walker was good. In fact, President William Howard Taft, John D. Rockefeller, and Booker T. Washington all came to hear his services.

Walker was also a very early pioneer in the civil rights movement. In 1891, after visiting the Holy Land, he began to criticize the “separate but equal” doctrine ever more vehemently. Commenting on black migration after the Civil War, he said, "It was a mistake for blacks to leave the South, since prejudice was national and not sectional.” And at a speech in Carnegie Hall before 8,000: "The Negro is an American citizen. The amendment to the Constitution did not make us men; God made us men before man made us citizens!" Bear in mind, Walker was saying these things at the turn of the 20th Century. Very brave, indeed.

At first, the Tabernacle Baptist Church was a two-story brick building on Ellis St. that held 800 worshippers. In 1915, a move was made to a striking building on Laney-Walker Boulevard with twin sanctuaries which could seat 2300, just a couple blocks from Walker’s home, shown at left. The church has been restored and is where Walker was buried when he died in 1921. His obituary appeared in the New York Times with the headline, “Augusta Pastor Was Called Greatest Negro Preacher of His Time.”

At first, the Tabernacle Baptist Church was a two-story brick building on Ellis St. that held 800 worshippers. In 1915, a move was made to a striking building on Laney-Walker Boulevard with twin sanctuaries which could seat 2300, just a couple blocks from Walker’s home, shown at left. The church has been restored and is where Walker was buried when he died in 1921. His obituary appeared in the New York Times with the headline, “Augusta Pastor Was Called Greatest Negro Preacher of His Time.”

So strong did Walker’s influence remain that the Tabernacle Baptist Church could not help but become a focal point in the Civil Rights struggles of the 1960’s. In 1962, Martin Luther King, Jr. spoke at a meeting of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference held there, the torch having clearly been passed.

So, that is just some of what’s known about Reverend Charles T. Walker. All I can tell you about his house is that it’s been painted pink and is in a very bad state. The house next door, pictured above, has burnt and it seems only a matter of time before a similar fate will befall the former home of the Black Spurgeon. Some things that can be photographed might disappear, but other things that are harder to see with the eye may not.

I’ve never taken a picture of the Tabernacle Baptist Church, which is dumb. But the photo at the top of the Highway Holiness Church was shot near the junkyard on the Aiken-Augusta Highway. The Full Gospel House of Prayer is on Sand Bar Ferry. The Deacon asked me just what I was doing in front of his church after I took that photo. I don’t think he was very impressed when I told him. Sorry, Deacon, there was no disrespect intended. I hope that's clear from the photo. Heart’s Full House might once have been a house of a different type of worship, but its soul has disappeared. The house below would be the next on the left in the shot above. So, you can see that the problems in the neighborhood are not exactly isolated.

If you want to read more about Reverend Walker, his biography is available on-line right HERE. The wonderful quotes came from an article in the Augusta Chronicle which is no longer on-line. I grabbed a bit of background from former Congressman Barrow's old website and a long-gone Georgia tourism page.

One of the buildings I really wanted to visit on this last trip to Augusta, Georgia was Lam Brothers Food Store at 1024-1026 D’Antignac St. Jack Lam, whose family emigrated from China, opened the store with his father and brother shortly after their arrival in 1941. I believe the building was already there by then, having been constructed in what was once an Irish neighborhood prior to Jim Crow zoning laws really sinking in their teeth early in the 1900’s. Eventually, Jack’s father and brother moved on and he ran the store solo, sometimes working “twenty-four hours a day.” Jack Lam also helped other Chinese people come to the U.S. and become citizens, earning himself an award from the Daughters of the American Revolution in 1972 for his work. Lam thought a hand-painted sign in the front window of the store symbolized his journey and success. It read, “Old-Fashioned Butcher Shop.” I guess he liked the old ways. Some information would indicate that they even served dim sum at the store.

One of the buildings I really wanted to visit on this last trip to Augusta, Georgia was Lam Brothers Food Store at 1024-1026 D’Antignac St. Jack Lam, whose family emigrated from China, opened the store with his father and brother shortly after their arrival in 1941. I believe the building was already there by then, having been constructed in what was once an Irish neighborhood prior to Jim Crow zoning laws really sinking in their teeth early in the 1900’s. Eventually, Jack’s father and brother moved on and he ran the store solo, sometimes working “twenty-four hours a day.” Jack Lam also helped other Chinese people come to the U.S. and become citizens, earning himself an award from the Daughters of the American Revolution in 1972 for his work. Lam thought a hand-painted sign in the front window of the store symbolized his journey and success. It read, “Old-Fashioned Butcher Shop.” I guess he liked the old ways. Some information would indicate that they even served dim sum at the store.

Lam ran the business for just over 50 years, meaning he probably left the building in the early 1990’s and, as far as I know, no one else ever moved in. I have to wonder if Lam drove past his old store every now and then, watching it slowly decay as vandals and drug addicts took it over. He is said to have loved driving through town in large automobiles. Or maybe he stayed away, knowing he’d only become saddened by what he saw.

Lam died on July 7, 2006 at the age of 85. It was certainly a blessing that he did not have to hear of the murder of 31-year-old Lawanda Person Tanksley nearly five years later in the place where he’d done his life’s work. It was May 15, 2011 when Ms. Tanksley’s body was found in Lam’s Store. As far as I know, her murderer has never been found.

Lest anyone think that my last post was overly dramatic or that roaming around vacant buildings—even historical vacant buildings—is without a very real risk, I would submit the example of Lam’s Store. Exploring old buildings is not something I have EVER recommended to anyone. It is often unwise and much better left to the pathologically compelled. To come upon a dead body would be bad enough. To come across the murderer might prove fatal.

Lest anyone think that my last post was overly dramatic or that roaming around vacant buildings—even historical vacant buildings—is without a very real risk, I would submit the example of Lam’s Store. Exploring old buildings is not something I have EVER recommended to anyone. It is often unwise and much better left to the pathologically compelled. To come upon a dead body would be bad enough. To come across the murderer might prove fatal.

That said, Lam’s was a unique and beautiful building with a long history. Having missed a chance to visit pre-murder, when I was back in Augusta in the spring of 2010, I was looking forward to finally checking it out. However, another drawback of documenting abandoned buildings is that they tend to unexpectedly disappear. Such was the case with Lam’s Store. Aside from its structural problems, after the murder the building’s reputation was so tarnished that there wasn’t much left to do but take it down. Now there’s just grass where Jack Lam spent over 50 years of his life.

The only photos I've ever seen of the inside of Lam’s Store are HERE. Note that the photographer strongly dissuades anyone from visiting and was clearly unnerved by the murder and the drug paraphernalia scattered over the floor. But they also found the remains of an old piano and, hey, that’s pretty cool, right?

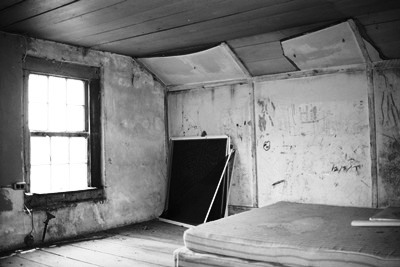

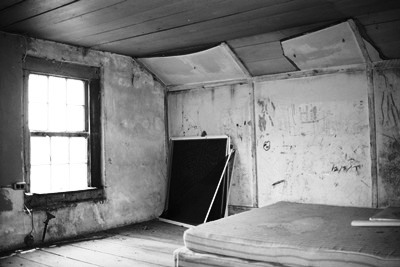

So, instead of stepping into Lam Brothers Food Store, you mostly get photos taken at 811 D’Antignac St., just a couple blocks away. Also vacant for years, 811 D’Antignac was built somewhere between 1850 and 1870 in the Greek Revival style. Its owner was Atlanta Gas Light Co. as late as 2006 and I suppose they might still own the place. Beyond that, I can find no record of who has lived in the house or what they might have done with their lives. Anyone?

I got some of the background for this post from this article on Augusta's African-American landmarks, but mostly I used Jack Lams' obituary and a crime report. The Lam’s Store photo is from the Chronicle and it physically pains me to put it here knowing I never got a shot of the building. Like I said, pathologically compelled.

We’ll make one more quick stop at an historic house I didn’t get into and thus walked away from with nothing but a few mediocre external shots. That will make three. Then, we’ll re-visit the remaining two of the original three upper Broad Street houses and, for our final Central Savannah River Area post, we’ll check out the empty field that was once a major concert destination in South Carolina to see if we can hear the ghosts of Duke Ellington and Cab Calloway on the wind.

Back in 2005, I wrote a post called Access Denied in which I described why I hadn’t photographed a particular part of Augusta, Georgia. This area included streets to the south of Walton Way and north of Laney-Walker Boulevard, bounded by Augusta’s famed medical colleges to the west and East Boundary to the, uh, east. Historically, this rectangle of neighborhoods was known as “The Terry,” a contraction of “Negro Territory.” This is where James Brown grew up and, at the time, I lamented not feeling that I could safely visit Twiggs St., where his childhood home had been, as I’d been told it was amongst Augusta’s “poorest and most dangerous neighborhoods.” I’d heard rumors ranging from the streets being unpaved to police not bothering to patrol. I sheepishly mentioned that I had at least driven through those streets. And they did appear to at least be paved.

A short while after I posted that piece, a commenter took me to task for not only believing what I’d been told, but for letting my wariness get in the way of visiting some historic places and taking some photos. This person dispelled many of the rumors and told me of the friendly, hard-working people that lived in the vicinity. The commenter wrapped-up by inviting me to visit these neighborhoods with them and see for myself the streets they‘d known most of their life. Of course, they were absolutely right. Mostly.

While my visits to Augusta since have been brief, not allowing me the time to contact the commenter and see if their offer still stands, I have gotten to know the neighborhoods I was referring to rather well. I even did an entire post on the address where James Brown grew up, his actual home, which also housed his aunt’s brothel, having long-since been torn down.

In Access Denied, I referenced “Stranger with a Camera,” a documentary about a film crew that ventured into rural Kentucky in the 1960’s to juxtapose the poverty there with footage they’d captured in more affluent parts of the country. While some people were happy to be filmed, hoping that the exposure might bring attention and federal aid, others were not so thrilled to have outsiders meddling in their business. On the last day of filming in Letcher County, Hobart Ison, a landlord who owned some houses where families were being interviewed, shot at the crew, killing Scottish Canadian photographer Hugh O’Connor. Ison was never convicted of any wrongdoing, the photographer, after all, having been on his property.

“Stranger with a Camera,” is required viewing for anyone interested in the fine line between documentation and exploitation, empathy and intrusion. Many of the messages of the film remain pertinent, among them this: “If you have a camera, be careful where you point it.” While it might have been silly of me to be intimidated by the things I’d heard about The Terry, that doesn’t mean that prudence was unwarranted. If that was the case in the neighborhoods I just described, it’s even more true farther south on Twiggs, where the historic Dr. Scipio S. Johnson House can be found.

Located in a part of Augusta known as the Bethlehem Historic District, this stretch of Twiggs, near where it becomes Martin Luther King, Jr. Blvd, is about as blown out a collection of streets as a person could find. The reasons include the usual socio-economic ones that plague many American cities. The history of this district is indeed rich, as described by the National Park Service in a piece that doesn't quite show the whole picture, I'd say. I would certainly love to know more about the district and the fascinating buildings that line its streets, now mostly empty shells. But this is where I have to depart from my commenter just a bit. For me to blithely roam around Old Savannah Rd. or 12th St. or parts of Wrightsboro Rd. on my own, poking my head in the open doorways of vacant buildings, rental car parked at the end of the street, camera around my neck, would be a kind of naivety that I’m just not a fan of. It might even be disrespectful. But I had a look at the S. S. Johnson House, feeling much as I did when I heard the stories of the film crew in Kentucky, “If something goes wrong, at least you shouldn’t say that you didn’t know what you were getting into.”

Now, Scipio S. Johnson was an African-American doctor who lived at 1420 Twiggs St. (pictured above) from the time the house was built in the 1920’s until his death in 1932. Dr. Johnson was a graduate of the Haines Institute, the Lincoln Institute, and Georgetown University. Nearby Johnson St. is, in fact, named for him. He was also a pharmacist and for a time ran a drug store right out of 1420. The two-story, Craftsman-style brick home is one of the largest in the Bethlehem District but it’s in pretty bad shape. The windows, which were considered historic in themselves, have been replaced by plywood. At least the boards were nailed-up tight enough not to tempt me. And that second story porch in the photo below is rather rickety. Who knows what’s gone on inside at this point? In late 2011, the house was added to Historic Augusta’s Endangered Properties List.

However, there is hope for the place. The Augusta, Georgia Land Bank Authority currently owns the property and intends to restore it as part of the Laney-Walker/Bethlehem Revitalization Project. That project will preserve another historic structure on Twiggs, the W.S. Hornsby House, while removing many adjacent structures. The plan calls for Twiggs St. to eventually be widened and the surrounding streets to be included in a “Twiggs Circle” development. Whether this will play out to the ultimate good of those who currently live in the area is anyone’s guess, but the problems have certainly attracted attention. In the meantime, if that commenter happens to read this: I’d still like to take you up on your offer of a tour, but maybe we could also check out some of the Bethlehem Historic District. It sounds like many of these buildings aren’t long for the world. Any chance?

Information for this post came from Historic Augusta and the Augusta Chronicle’s piece on the Laney-Walker/Bethlehem revitalization plan. The photos were all taken on or near Twiggs St. The shot at the very top is of the Denning House at 905 7th St., just before 7th becomes Twiggs. Built in the 1860's, it was on Historic Augusta's 2007 Endangered Properties list and looked a little better back then.

Who would’ve thought I’d come back from a few days in Augusta with so much material? Next time we’ll head back north a few streets to 811 D’Antignac, a vacant house built in 1870 which served as a consolation prize for me after my main structure of interest was torn down.

Back in the 1830’s, just a few years after the dawn of photography, when people were making images on pewter and glass (actually, I think I’d like to make some images on pewter and glass right now), one of the two major pioneers in the field, William H. Fox Talbot, said that photography documents “the injuries of time,” particularly when a contemporary photo is set side-by-side with an earlier shot. The guy had a strong point.

Looking back over City of Dust, I guess most of my photography is explicitly concerned with the “injuries of time.” And even though I rarely have a “before” picture for comparison, the injuries are still pretty obvious. In the case of Augusta, Georgia's Goodale Inn, I don’t need a photogravure of the house made thirty years after its construction in 1799 to witness the ravages of time. I can simply compare a photo I took this past fall with a shot from a visit less than a decade ago. So, let’s take another trip to the Goodale Inn, probably the oldest four-sided brick building in Georgia and possibly one of the oldest largely unaltered structures in the state, period. Although, as you will see, alterations are taking place whether anyone wants them to or not.

Located way out at 745 Sand Bar Ferry Rd., the Goodale Inn was once the first structure travelers saw when entering Augusta from South Carolina, the state line being somewhere in the Savannah River just to the east, the crossing still known as Goodale's Landing. Imagine how many people have gone past the Goodale Inn on horseback and by carriage, including aging Revolutionary War veterans and Civil War soldiers. However, the house may never actually have been an inn.

The building is on land that was owned by Thomas Goodale as part of the 500-acre Goodale Plantation. Goodale also operated the Sand Bar Ferry, bringing travelers across the river. The Goodale Inn might have been built by Charles Goodale, or maybe it was built by Christopher Fitzsimmons, who is reported to have bought the land around 1799-1800. There is some mystery in that chronology, actually. Later, the property was given by Fitzsimmons to Governor Wade Hampton III’s father as part of his daughter Ann’s dowry. The place has quite a history and if you want to read more and see a few photos depicting a less battered Goodale, you can find my original post HERE. Of course, a building this old has to be haunted and the resident ghost is supposedly that of a little girl who turns on lights and slams doors, amongst other things. Particularly in the attic. Well, it is true that the attic light was often on when I’d drive past at night.

Inside the Goodale are ten rooms and five fireplaces to keep warm. Some bricks have now been pulled out of those fireplaces by “treasure hunters” (read: vandals) who believed there might be Confederate gold or something sealed up in the chimneys. Rumors of a previous owner digging up "Indian mounds" in the backyard while searching for said gold may or may not be exaggerated. Now, if you look closely at the photo that starts this post, you will see that one of the metal treads at the top of the steps is missing. Hopefully this has just been removed by the owners and not actually stolen and recycled for 0.50/lb. You will also see a rectangular wooden frame on the lower part of the front porch. This used to hold a banner that read, “Save the Goodale.” But now even that is gone. All of this is actually small potatoes to the major injury that has befallen the Goodale, shown in the photo just above. Yup, the entire western wall has collapsed leaving one side of the building open to the elements and very vulnerable.

Inside the Goodale are ten rooms and five fireplaces to keep warm. Some bricks have now been pulled out of those fireplaces by “treasure hunters” (read: vandals) who believed there might be Confederate gold or something sealed up in the chimneys. Rumors of a previous owner digging up "Indian mounds" in the backyard while searching for said gold may or may not be exaggerated. Now, if you look closely at the photo that starts this post, you will see that one of the metal treads at the top of the steps is missing. Hopefully this has just been removed by the owners and not actually stolen and recycled for 0.50/lb. You will also see a rectangular wooden frame on the lower part of the front porch. This used to hold a banner that read, “Save the Goodale.” But now even that is gone. All of this is actually small potatoes to the major injury that has befallen the Goodale, shown in the photo just above. Yup, the entire western wall has collapsed leaving one side of the building open to the elements and very vulnerable.

Now, before you say, “This is outrageous! The owner of the Goodale Inn should be ashamed for letting this historic structure crumble! Where can I find him so that I might give him a piece of my mind?”, let’s step back for a moment. When I visited the Goodale in 2004 it was long-vacant and long for sale. Following a couple foreclosures, the property was finally auctioned off in 2009 to an Alabama investor with hopes of restoration. This investor paid less than $20,000, which is a fair step down from the original asking price of $250,000. If you think that buying a house built in 1799 for $20,000 might somehow indicate that there are problems, I suspect you’re right. That's the little girl's attic in the photo above, taken in 2004.

It was August of 2011 when the wall collapsed. Since then I’ve been in touch with people that have worked on the house who've said that some of the river rock used for the foundation has turned into a fine powder that now sits in little piles along the bottom of the basement walls. The heart of pine floors are held together with wooden pegs. Cool, but not easy to upgrade. In short, this is no simple fixer-upper. To me, it seems that those that own the Goodale Inn and are working for its restoration have their hearts in the right place. Remember, literally no one else wanted the place. Not the city, not the county, not the state. NO ONE. As for the slow progress on the restoration, I’ve heard that money doesn’t grow on trees. Those are some heart of pine beams above. Below is the Goodale Inn circa 2004. Note the presence of the chimney.

It was August of 2011 when the wall collapsed. Since then I’ve been in touch with people that have worked on the house who've said that some of the river rock used for the foundation has turned into a fine powder that now sits in little piles along the bottom of the basement walls. The heart of pine floors are held together with wooden pegs. Cool, but not easy to upgrade. In short, this is no simple fixer-upper. To me, it seems that those that own the Goodale Inn and are working for its restoration have their hearts in the right place. Remember, literally no one else wanted the place. Not the city, not the county, not the state. NO ONE. As for the slow progress on the restoration, I’ve heard that money doesn’t grow on trees. Those are some heart of pine beams above. Below is the Goodale Inn circa 2004. Note the presence of the chimney.

But there is some hope yet. A recent structural survey, financed by a $5,000 “intervention grant” from the National Trust for Historic Preservation, found that most of the house is still basically sound. At least it doesn’t need to be torn down. Also, ownership of the house will apparently be transferred to a new non-profit, the Historic Home Preservation Society, allowing better access to grant money that’s available for restoration projects. So we shall see. If anyone reading this has some extra funds lying around and would like to help the Goodale Inn, I’m sure you can contact the owners through their Facebook page, Save the Goodale. The ghost of a shy little girl would most certainly thank you.

Information and inspiration for this post came from an article entitled, "Engineers Say Most of Goodale House Still Stable," in the Augusta Chronicle on the positive outcome of the structural survey. More about the collapse of the wall is HERE. As usual, Historic Augusta has some good background, too. I got the great old shot above from the Save the Goodale Facebook page where it was uncredited. Try to guess the date (note car at right). It appears to pre-date the period in the 1970's when the Goodale was a "free school" prior to a restaurant being put in the basement. I hear the restaurant served a delicious peanut butter pie on pewter dishes, which brings us all the way back to where we started.

Next time we’ll head into south Augusta to see the historic Dr. Scipio S. Johnson House at 1420 Twiggs St. It ain’t looking good.

At first, the Tabernacle Baptist Church was a two-story brick building on Ellis St. that held 800 worshippers. In 1915, a move was made to a striking building on Laney-Walker Boulevard with twin sanctuaries which could seat 2300, just a couple blocks from Walker’s home, shown at left. The church has been restored and is where Walker was buried when he died in 1921. His obituary appeared in the New York Times with the headline, “Augusta Pastor Was Called Greatest Negro Preacher of His Time.”

At first, the Tabernacle Baptist Church was a two-story brick building on Ellis St. that held 800 worshippers. In 1915, a move was made to a striking building on Laney-Walker Boulevard with twin sanctuaries which could seat 2300, just a couple blocks from Walker’s home, shown at left. The church has been restored and is where Walker was buried when he died in 1921. His obituary appeared in the New York Times with the headline, “Augusta Pastor Was Called Greatest Negro Preacher of His Time.”

One of the buildings I really wanted to visit on this last trip to Augusta, Georgia was Lam Brothers Food Store at 1024-1026 D’Antignac St. Jack Lam, whose family emigrated from China, opened the store with his father and brother shortly after their arrival in 1941. I believe the building was already there by then, having been constructed in what was once an Irish neighborhood prior to Jim Crow zoning laws really sinking in their teeth early in the 1900’s. Eventually, Jack’s father and brother moved on and he ran the store solo, sometimes working “twenty-four hours a day.” Jack Lam also helped other Chinese people come to the U.S. and become citizens, earning himself an award from the Daughters of the American Revolution in 1972 for his work. Lam thought a hand-painted sign in the front window of the store symbolized his journey and success. It read, “Old-Fashioned Butcher Shop.” I guess he liked the old ways.

One of the buildings I really wanted to visit on this last trip to Augusta, Georgia was Lam Brothers Food Store at 1024-1026 D’Antignac St. Jack Lam, whose family emigrated from China, opened the store with his father and brother shortly after their arrival in 1941. I believe the building was already there by then, having been constructed in what was once an Irish neighborhood prior to Jim Crow zoning laws really sinking in their teeth early in the 1900’s. Eventually, Jack’s father and brother moved on and he ran the store solo, sometimes working “twenty-four hours a day.” Jack Lam also helped other Chinese people come to the U.S. and become citizens, earning himself an award from the Daughters of the American Revolution in 1972 for his work. Lam thought a hand-painted sign in the front window of the store symbolized his journey and success. It read, “Old-Fashioned Butcher Shop.” I guess he liked the old ways.

Lest anyone think that my

Lest anyone think that my

Inside the Goodale are ten rooms and five fireplaces to keep warm. Some bricks have now been pulled out of those fireplaces by “treasure hunters” (read: vandals) who believed there might be Confederate gold or something sealed up in the chimneys. Rumors of a previous owner digging up "Indian mounds" in the backyard while searching for said gold may or may not be exaggerated. Now, if you look closely at the photo that starts this post, you will see that one of the metal treads at the top of the steps is missing. Hopefully this has just been removed by the owners and not actually stolen and recycled for 0.50/lb. You will also see a rectangular wooden frame on the lower part of the front porch. This used to hold a banner that read, “Save the Goodale.” But now even that is gone. All of this is actually small potatoes to the major injury that has befallen the Goodale, shown in the photo just above. Yup, the entire western wall has collapsed leaving one side of the building open to the elements and very vulnerable.

Inside the Goodale are ten rooms and five fireplaces to keep warm. Some bricks have now been pulled out of those fireplaces by “treasure hunters” (read: vandals) who believed there might be Confederate gold or something sealed up in the chimneys. Rumors of a previous owner digging up "Indian mounds" in the backyard while searching for said gold may or may not be exaggerated. Now, if you look closely at the photo that starts this post, you will see that one of the metal treads at the top of the steps is missing. Hopefully this has just been removed by the owners and not actually stolen and recycled for 0.50/lb. You will also see a rectangular wooden frame on the lower part of the front porch. This used to hold a banner that read, “Save the Goodale.” But now even that is gone. All of this is actually small potatoes to the major injury that has befallen the Goodale, shown in the photo just above. Yup, the entire western wall has collapsed leaving one side of the building open to the elements and very vulnerable.

It was August of 2011 when the wall collapsed. Since then I’ve been in touch with people that have worked on the house who've said that some of the river rock used for the foundation has turned into a fine powder that now sits in little piles along the bottom of the basement walls. The heart of pine floors are held together with wooden pegs. Cool, but not easy to upgrade. In short, this is no simple fixer-upper. To me, it seems that those that own the Goodale Inn and are working for its restoration have their hearts in the right place. Remember, literally no one else wanted the place. Not the city, not the county, not the state. NO ONE. As for the slow progress on the restoration, I’ve heard that money doesn’t grow on trees. Those are some heart of pine beams above. Below is the Goodale Inn circa 2004. Note the presence of the chimney.

It was August of 2011 when the wall collapsed. Since then I’ve been in touch with people that have worked on the house who've said that some of the river rock used for the foundation has turned into a fine powder that now sits in little piles along the bottom of the basement walls. The heart of pine floors are held together with wooden pegs. Cool, but not easy to upgrade. In short, this is no simple fixer-upper. To me, it seems that those that own the Goodale Inn and are working for its restoration have their hearts in the right place. Remember, literally no one else wanted the place. Not the city, not the county, not the state. NO ONE. As for the slow progress on the restoration, I’ve heard that money doesn’t grow on trees. Those are some heart of pine beams above. Below is the Goodale Inn circa 2004. Note the presence of the chimney.