skip to main |

skip to sidebar

My favorite place to photograph in Albuquerque--by far--is the long-vacant Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe Rail Yard. A couple years ago I did an epic post on this “industrial cathedral,” recounting its storied history and featuring lots of photos. A short time later I collected my favorite rail yard shots and made a small book. So, I’m very pleased to announce that I’ll be selling framed prints of the rail yard at this year’s WHEELS Museum Gala Dinner honoring Mayor Richard Berry.

The gala will be held on April 20, 2013, beginning at 5PM with an auction. The event is also a fundraiser for the WHEELS Museum. For years, WHEELS has worked tirelessly to keep the rail yard in the public eye and ensure that any development plans incorporate the incredible buildings that make the place what it (still) is.

Now, tickets to events featuring the mayor don’t come cheap and the going rate is $100/plate or $1000/table. If you can't quite swing that just drop me a line at the e-mail address associated with my profile and I bet we can work something out.

I’d like to thank everyone at the WHEELS Museum for this great opportunity. More information can be found below or at WHEELS WEBSITE. I hope to see you there!

Before we leave Georgia, let’s take a quick look at the Augusta Confederate Monument, located in the grassy median of the 700 block of Broad Street, across from the Marion Building. Seventy-six feet tall with a Georgia granite base and the rest entirely of Italian marble, the monument is fairly imposing. Financed by the Ladies Memorial Association, it cost $17,331.35 to build, which wasn’t chicken feed in the 19th Century. But I admit that I drove past it every day for two years and never knew anything about it. I'm sure I wasn't the only one.

Before we leave Georgia, let’s take a quick look at the Augusta Confederate Monument, located in the grassy median of the 700 block of Broad Street, across from the Marion Building. Seventy-six feet tall with a Georgia granite base and the rest entirely of Italian marble, the monument is fairly imposing. Financed by the Ladies Memorial Association, it cost $17,331.35 to build, which wasn’t chicken feed in the 19th Century. But I admit that I drove past it every day for two years and never knew anything about it. I'm sure I wasn't the only one.

Monuments to the Confederacy can be found throughout the South and Augusta’s is considered to be the most striking in Georgia. Dedicated on Halloween 1878, 10,000 people attended the unveiling. The four statues at the base are of Generals Robert E. Lee, Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, William H. T. Walker, and Thomas R. R. Cobb. But perhaps of most interest is the more obscure figure at the top, Private Berry Greenwood Benson, born across the Savannah River in Hamburg, South Carolina in 1843. If you want to read more about that infamous (and now entirely disappeared) town and the controversial memorial that commemorates a particularly bloody day in the summer of 1876, a year after Augusta's Confederate Monument was commissioned, you can see my post on Hamburg HERE.

But I digress. Private Benson was initially a member of the Hamburg Minutemen. He was captured by the Union in 1864 while fighting for Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia and sent to Point Lookout in Maryland. Benson escaped by swimming two miles across Chesapeake Bay. After rejoining the fighting, he was captured again and eventually sent to a military prison in New York from which he tunneled out and then walked back to his regiment. Following Appomattox, Benson returned to Augusta with his rifle, having refused to agree to the surrender. Regardless of your feelings about the Civil War, you have to admire the guy’s tenacity. It’s what made him "the man on the monument," after all.

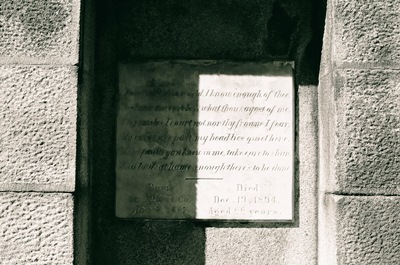

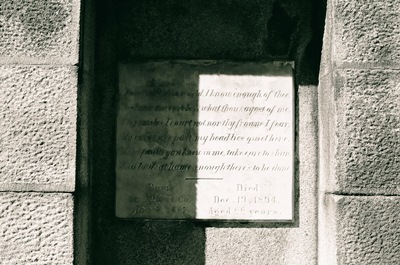

The inscription in the photo at the very top reads:

In Memoriam. No nation rose so white and fair: None fell so pure of crime.

Make of that what you will. But, in 2009, the monument was vandalized with spray-painted phrases that included, "I hate whites" and "cracker killers," amongst others. What d'ya know? I guess some people do read the thing. Interestingly, public opinion largely attributed the graffiti to white kids.

Probably I should have gotten some more photos of the monument, including a shot of Benson’s statue (duh), but instead I'll use the incredible shot above, taken while the Marion Building burned in March 1916. Other inscriptions on the monument read:

Worthy to have lived and known our gratitude

Worthy to be hallowed and held

In tender remembrance

Worthy the fadless fame which

Confederate soldiers won

Who gave themselves in life

And death for us

For the honor of Georgia

For the rights of the States

For the liberties of the South

For the principles of the Union, as these were handed down to them,

By the fathers of our common Country.

Our Confederate Dead

Erected A.D. 1878 by the Memorial Association of Augusta,

In honor of the men of Richmond County,

Who died in the cause of the Confederate States.

You can find more information about Augusta’s Confederate Monument on Wikipedia. Also, ‘Gusta in the Wa’er provided some useful tidbits. The picture of the 1916 fire came from the Augusta Chronicle. The Augusta Chronicle also did a piece on the 2009 defacement.

Now it’s over to South Carolina to investigate the night life of the 1940’s and 50’s.

In 2005, I wrote a piece about Magnolia Cemetery and some of the people buried there. One of the most interesting stories was that of Wylly Barron. At the time, I didn’t have any photos of Wylly’s grave. But I paid him a visit last fall and finally got some shots. So, I think it’s worthwhile to reprise the tale of Mr. Barron, now with the proper photographs to accompany.

Magnolia Cemetery, designated as such in 1818, is the oldest boneyard in Augusta. In fact, the first grave was actually dug in 1800. Wylly Barron, once the gambling manager at the Atkinson Hotel on Ellis Street, not far from the Genesta Hotel, is literally cemented into a concrete mausoleum there, the bitter end of his sad story.

The story goes that a gambler at the Atkinson killed himself following some heavy losses, but before he did he cursed poor Wylly, saying, "You have taken everything I have. When you die, may you not even have a grave to shelter you." This spooked Wylly to no end and he started enforcing all sorts of regulations in his parlor to ease his conscience. People that handled money for their jobs couldn't gamble (they might steal), nor could minors. He also secretly gave money to anyone that had fallen upon hard luck and asked him for help. But, perhaps most importantly, in 1870 he had a mausoleum built in Magnolia Cemetery so he'd be certain there WOULD be a grave to shelter him. Good thing he did, too.

While Wylly Barron had led an extravagant life in his younger days, by the time of his death on December 18, 1894 at age 88, he'd lost all of his wealth. He was so broke a proper coffin couldn't even be purchased and his body was simply sealed up in the mausoleum. Then the keys to the mausoleum door--which was sealed shut anyway--and the encircling iron fence were thrown in the Savannah River, as he'd decreed in his will, so no one could ever remove him from his sheltering grave. His final epitaph reads: “Farewell vain work, I know enough of thee. And now am careless what thou sayest of me. Thy smiles I court not, nor thy frowns I fear. My cares are past, my head lies quiet here. What faults you knew of me, take care to shun. And look at home, enough there’s to be done.”

And that's how Wylly Barron beat the curse of a vengeful gambler.

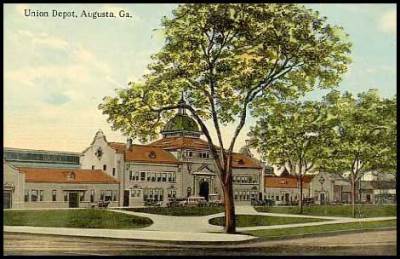

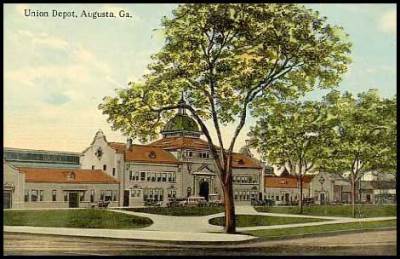

In the last post, which featured the Genesta Hotel, I mentioned the importance of Union Station in the development of 8th (aka Jackson) Street, once known as the “White Way” for its bright streetlamps, which burned all night long, guiding travelers to and from the nearby trains. Union Station itself was at 525 8th St., on Walker, and designed in the Spanish Renaissance style by Frank P. Milburn. Construction was completed in 1903 and the building fronted a leafy public space known as Barrett Square.

In the last post, which featured the Genesta Hotel, I mentioned the importance of Union Station in the development of 8th (aka Jackson) Street, once known as the “White Way” for its bright streetlamps, which burned all night long, guiding travelers to and from the nearby trains. Union Station itself was at 525 8th St., on Walker, and designed in the Spanish Renaissance style by Frank P. Milburn. Construction was completed in 1903 and the building fronted a leafy public space known as Barrett Square.

Union Station served the Atlantic Coast, Georgia, Southern, Central of Georgia, Charleston & Western Carolina, and Georgia & Florida railroads. That’s a lot of trains coming and going and, indeed, the station was large and majestic. So, naturally, it was torn down in 1972, four years after the last passenger had disembarked, and now a post office occupies the site.

There is practically nothing in Augusta that would indicate that Union Station, once one of the most important buildings in the city, ever existed. I say practically nothing, because one thing does exist. Tucked unceremoniously into an out-of-the-way piece of tree-obscured lawn on Telfair Street, right in front of the Old Academy of Richmond County, stands the original cupola. You can even climb inside and imagine that you’re on top of Union Station, looking out at an early 20th Century scene, perhaps marveling at the smoky, bustling city and trying to remind yourself that in about 80 years you really should buy some Microsoft stock.

because one thing does exist. Tucked unceremoniously into an out-of-the-way piece of tree-obscured lawn on Telfair Street, right in front of the Old Academy of Richmond County, stands the original cupola. You can even climb inside and imagine that you’re on top of Union Station, looking out at an early 20th Century scene, perhaps marveling at the smoky, bustling city and trying to remind yourself that in about 80 years you really should buy some Microsoft stock.

The historic postcard picture came from Rail GA, a website which seems to have disappeared. That’s also where I got much of the information for this post. The Old Academy of Richmond itself, seen in the background of the top photo, has been recognized by the National Park Service’s Historic American Buildings Survey. You can read more about the place HERE.

Next post we’re going to (re)visit a dead man.

Before we leave Georgia, let’s take a quick look at the Augusta Confederate Monument, located in the grassy median of the 700 block of Broad Street, across from the

Before we leave Georgia, let’s take a quick look at the Augusta Confederate Monument, located in the grassy median of the 700 block of Broad Street, across from the

In the last post, which featured the

In the last post, which featured the

because one thing does exist. Tucked unceremoniously into an out-of-the-way piece of tree-obscured lawn on Telfair Street, right in front of the Old Academy of Richmond County, stands the original cupola. You can even climb inside and imagine that you’re on top of Union Station, looking out at an early 20th Century scene, perhaps marveling at the smoky, bustling city and trying to remind yourself that in about 80 years you really should buy some Microsoft stock.

because one thing does exist. Tucked unceremoniously into an out-of-the-way piece of tree-obscured lawn on Telfair Street, right in front of the Old Academy of Richmond County, stands the original cupola. You can even climb inside and imagine that you’re on top of Union Station, looking out at an early 20th Century scene, perhaps marveling at the smoky, bustling city and trying to remind yourself that in about 80 years you really should buy some Microsoft stock.