skip to main |

skip to sidebar

There are two ghost towns by the name of San Pedro in New Mexico. One is a former gold mining town to the north, in Santa Fe County, but, since we’re still roaming around U.S. Highway 380 in the central part of the state, we’ll check out the one in Socorro County.

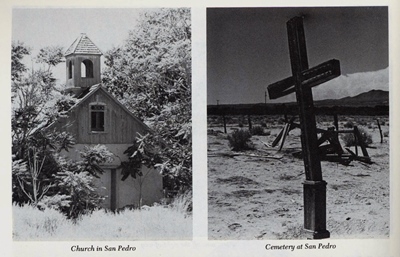

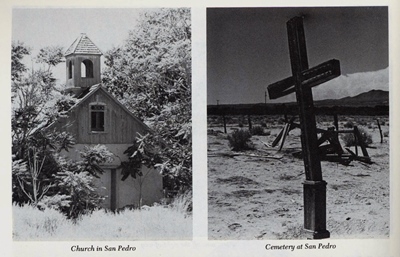

When Philip Varney visited San Pedro in the late-‘70s, he described a ghost town of more than a dozen buildings, including the wood and adobe San Pedro Catholic Church, complete with intact steeple, and another large adobe structure, once the home of a well-known landowner. Things have changed a bit over the last 30+ years and, while not exactly a booming metropolis, San Pedro is a little livelier than when Varney came through. Kinda like Chloride, but without the museum.

While there might be more actual residents these days (and perhaps meaner dogs, as well), there seems to be fewer buildings. The church is nowhere to be found, nor is the neighboring barbershop. The stately adobe residence has mostly sunk into the earth (and is guarded by one or two of the aforementioned pups). The schoolhouse, pictured at top, still remains though. Built by the W.P.A. in 1936, it closed shortly thereafter and is now owned by the family living next to it. They were kind enough to let me take a photo after finding me basically standing in their driveway when they came home one evening. Thanks, folks!

San Pedro was settled in the mid-1800s by two families, the Montoya’s and the Tefoya’s. By 1860, the town had a population of 223. At that time, the village, located on the east bank of the Rio Grande and close to El Camino Real, was a Spanish agricultural settlement known especially for its grapes. These grapes were crushed into wine reportedly shipped “all the way to Kansas.” The village was also a resting place and trading center for travelers on El Camino Real. Later, some residents became miners and worked in nearby Carthage and Tokay. Apparently, a heated baseball rivalry developed between the San Pedro and Tokay teams with a third forgotten community, Bosquecito, also in the mix.

located on the east bank of the Rio Grande and close to El Camino Real, was a Spanish agricultural settlement known especially for its grapes. These grapes were crushed into wine reportedly shipped “all the way to Kansas.” The village was also a resting place and trading center for travelers on El Camino Real. Later, some residents became miners and worked in nearby Carthage and Tokay. Apparently, a heated baseball rivalry developed between the San Pedro and Tokay teams with a third forgotten community, Bosquecito, also in the mix.

The Rio Grande, that lifeblood of San Pedro--as it was for so many small towns--was the reason for San Pedro’s location and, finally, a major reason for its decline. All that remains of the section of the river that used to pass beside San Pedro is a dry, sandy bed, the result of canals that have shifted the course of the waterway almost a mile to the west.

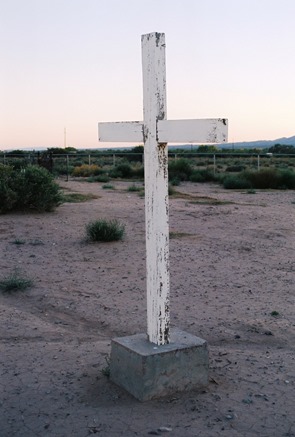

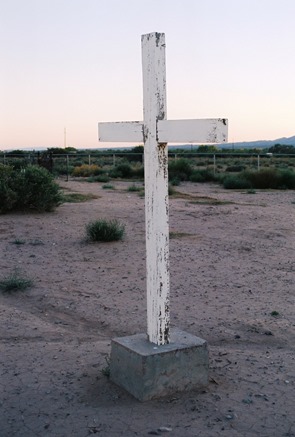

Varney described the San Pedro Cemetery as “windswept and desolate.” I love a nice, desolate, windswept cemetery, but in San Pedro the cemetery, too, has been modernized. A comparison of grave markers shows them to have been upgraded since Varney’s visit. While I have to admit that I prefer desolation, aesthetically-speaking, I’m happy for San Pedro. And I got in some desolate, windswept cemetery viewing in cold, cold Clayton last weekend.

We’ll get to Clayton and its famous decapitated dead man, Black Jack Ketchum, eventually, but we’re going to stay in sprawling Socorro County and head down to the banks of the Rio Salado to visit Riley (aka Santa Rita) next. Until then, be well, as both Garrison Keillor and Walgreens tell me these days.

Information for this post (and the b&w photos above) came from Philip Varney, of course. Additional help was courtesy of ghosttowns.com and, through them, Roadside New Mexico: A Guide to Historic Markers, Revised and Expanded Edition!

Last post we visited San Antonio, New Mexico, the spiritual home of the Hilton Hotels chain. San Antonio experienced a boom when coal mines ramped up production in Carthage, about 10 miles east. One of those early mines, the “Hilton,” was owned by August H. “Gus” Hilton. But, while San Antonio is still pretty hard to miss, especially if you’re looking for cranes at Bosque del Apache, three towns closely linked to San Antonio—Carthage, Tokay, and Frailey—have sunk deep into oblivion. In fact, even the true spelling of “Frailey” has been lost. You might see it referred to as “Fraley” or “Farlay” and either might be right. One spelling that is probably not correct is the one found on the NM Historic Marker beside nearby Highway 380, which has it as “Farley.” At top is what might have once been part of an auto garage, judging by nearby remains.

Carthage was the site of the first coal mine in New Mexico, the Government mine, which employed U.S. Army soldiers in the early 1860’s and supplied Forts Bayard, Selden, and Stanton. Construction of a railway to ship coal to San Antonio from Carthage began on March 1 of the year that seems to represent the zenith of the Wild West, 1881, when Billy the Kid died and there was a Gunfight at the O.K. Corral. I think the shot above might be the bottom of a tower used for watering locomotives.

The Santa Fe Railroad Co. finished a bridge across the Rio Grande in 1883 and, by 1889, Carthage topped the list of coal camps in the state with a population of about 300. But, by 1893, coal production was lagging, so the Santa Fe Railroad Co. made a deal to move the entire town to Cerrillos, NM. On August 17, 1893, the Old Abe Eagle reported, “…All the dwelling houses, coal chutes and machinery have already been moved. The place has practically been razed to the earth and the depot, adobe hotel and Gross, Blackwell and Co. are about all that remain.” The Santa Fe Railroad then promptly went into receivership on Christmas Eve. Almost two years later it would re-emerge as the famous Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe (AT&SF).

From 1894, coal extraction continued while mines changed hands and changed hands again. The abandoned Santa Fe Railroad Co. line finally ceased operating entirely in 1896 and then everyone spent some years trying to figure out how to get the railroad to run those 10 miles to San Antonio again. The difficulties of (re)building the short spur came to a head in 1905 when competing mining and railroad interests sued each other. Mining ceased for two years during the litigating. Finally, the case was settled out of court, 50 new miner’s homes were quickly built by the Carthage Coal Company, and production surged.

Then, on New Year’s Eve 1907, there was a massive explosion in the Bernal mine which killed nine miners, throwing two 300 yards from the site. Two more were seriously injured. It was said that many more would’ve been killed if it weren’t for the fact that the accident occurred during lunch and most men were eating. A somewhat lesser disaster struck Carthage on February 22, 1918, when coal dust ignited in the Government mine, killing one mine inspector who improperly used his safety equipment and a sparrow.

Mining continued for decades, but eventually with diminishing returns. The last train left Carthage on August 28, 1931. After that, things were really on the downswing, although serious mining interests struggled through into the 1940’s. The last mine, Tres Hermanos, was opened in 1980 by Cactus Industries. It was closed by 1981.

Now, if you look at the entry for Carthage on ghostowns.com, you will see a note dated April 2, 2000 which laments that most of what had remained of Carthage--apparently a fair amount--had recently been hauled off to a nearby dump. The “clean-up” was ostensibly part of a “desert restoration project” and, while I sure love the desert, I find this a little hard to believe. There is so much wide-open space in every direction out here that restoring this small area strikes me as bizarre. Not impossible though. On the other hand, “Ghost Towns and Mining Camps of New Mexico” stated in 1975: “Today what is left of Carthage is fast melting into oblivion.” Other than the impressive adobe ruins of the large home of a mine superintendent, John Hart, who left Carthage in the mid-1940’s, I have no idea what’s really been lost in the interim. At least the corpse of the small mining car above persists.

The “clean-up” was ostensibly part of a “desert restoration project” and, while I sure love the desert, I find this a little hard to believe. There is so much wide-open space in every direction out here that restoring this small area strikes me as bizarre. Not impossible though. On the other hand, “Ghost Towns and Mining Camps of New Mexico” stated in 1975: “Today what is left of Carthage is fast melting into oblivion.” Other than the impressive adobe ruins of the large home of a mine superintendent, John Hart, who left Carthage in the mid-1940’s, I have no idea what’s really been lost in the interim. At least the corpse of the small mining car above persists.

Whether Carthage disappeared recently or long ago, what remains now is hard to identify. Millions of pieces of broken glass glitter in the sun, a surprising percentage of them pink and purple. (So much for a restoration, eh?) A few stone foundations can be seen here and there. Several old mines can be located, all sealed and capped. Walking the raised rail trestle from the relatively intact Carthage Cemetery, it’s unclear where Carthage becomes Frailey, the site of a limestone quarry and kilns owned by Mr. J.B. Frailey, once the trainmaster at San Marcial, now also a ghostly town.

Then there’s Tokay, founded in 1918 by Bartley Hoyt Kinney, Sr., who was involved in the Carthage mines and organized the San Antonio New Mexico Coal Company. He wanted to name the town “Kinney,” but the post office refused. Finally, while talking to the postal inspector at Mr. Kinney’s general store, he saw a box of Tokay grapes and said, “How about Tokay?”

Tokay actually struggled into the late-1940’s, but eventually mining ceased and its structures were moved to Socorro. It would’ve been around here somewhere. But where? Who knows anymore? Just a few miles southeast is the Trinity Test Site, where, on July 16, 1945, the first atomic bomb was detonated. Carthage, Tokay, and Frailey, once sizable and active places, couldn’t be much more obliterated if they’d been at ground zero.

Hey, even Philip Varney didn’t have much to say about these three towns. There’s little to be found on Carthage, but, surprise, surprise, there is one scholarly article, “Mining History of the Carthage Coal Field, Socorro County, New Mexico.” It’s the best source, by far. I also consulted the aforementioned ghostowns.com. Even less can be found on Tokay and Frailey and what I managed to unearth was part of a good history of the railroad in the area formerly posted at New Mexico Wanderings. Old newspaper articles on the mine explosion can be found at gendisasters. And let's not forget Ghost Towns and Mining Camps of New Mexico by James E. and Barbara H. Sherman.

Next time, we’ll make a quick stop at San Pedro, just between Carthage and San Antonio.

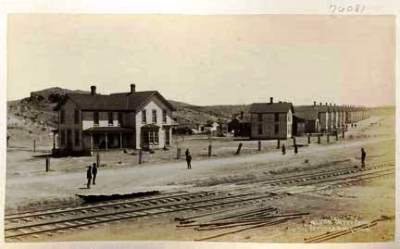

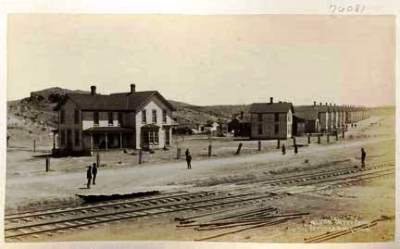

Around the turn of the 20th Century, a boy would walk from his father’s mercantile store, which also served as a hotel, to the train depot (shown above), just a short distance away. This boy then carried the luggage of passengers newly arrived in San Antonio, New Mexico back to their rooms, which ran $2.50 a day and included meals. The boy met every train stopping in town, regardless of time or weather. In 1919, that boy, Conrad Hilton, now thirty-two years old, bought the Mobley Hotel in Cisco, Texas and thus began the Hilton Hotels chain. Paris Hilton is his great-granddaughter.

Below is a shot of some almost 100-year-old graffiti from inside the depot. Note the infinity sign/hat brim. Could it be the mark of the original train-hopping Bozo Texino?

San Antonio can trace its history back to 1629 and the founding of the San Antonio de Senecú Mission. The Apaches succeeded in destroying the mission in 1675 and for over 100 years the burnt remains of the village, which had been inhabited by Piro Indians for a mere 700 years prior, slowly decayed out on the plains, a caution to travelers on the nearby Camino Real. Now those ruins have been fully reclaimed by nature and the exact location of San Antonio de Senecú is unknown. On the other hand, the Crystal Palace, below, was once a dance hall and then a much more dilapidated (and photogenic) auto garage, but someone eventually decided to kinda fix it up.

Hispanic farmers from northern New Mexico established present-day San Antonio in 1820 and, when the Santa Fe Railroad arrived in 1880, the town shifted to be closer to the rails. While most of San Antonio’s 1,250 residents still raised livestock, made wine, or even kept bees, the railroad was soon extended 10 miles east to reach the coal mines of Carthage and Tokay. Stakes included a claim known as the Hilton Mine, owned by A.H. “Gus” Hilton, who used the money to found the A.H. Hilton Mercantile Store. Mr. Hilton’s son, Conrad, was born on Christmas Day, 1887.

For almost 50 years the mines paid out, the trains came and went, and stagecoaches ran between White Oaks, Fort Stanton, and Lincoln. However, by 1925, the mines were going bust and the railroad soon took up its tracks. Then two major floods in 1929 washed away a big chunk of the town and the surrounding farmland. WWII lured away most remaining young men and A.H. Hilton’s original mercantile burnt around the same time, which, incidentally, pretty much coincided with Conrad's marriage to Zsa Zsa Gabor. However, Hilton’s wooden bar was saved and installed in the famous Owl Bar and Restaurant in 1945, where it is used to this day to support Tecate and green chile cheeseburgers. The Owl Bar itself was built by Brunswick Balke Collender Company. You might have used their bowling balls.

Then two major floods in 1929 washed away a big chunk of the town and the surrounding farmland. WWII lured away most remaining young men and A.H. Hilton’s original mercantile burnt around the same time, which, incidentally, pretty much coincided with Conrad's marriage to Zsa Zsa Gabor. However, Hilton’s wooden bar was saved and installed in the famous Owl Bar and Restaurant in 1945, where it is used to this day to support Tecate and green chile cheeseburgers. The Owl Bar itself was built by Brunswick Balke Collender Company. You might have used their bowling balls.

And that is largely where San Antonio is at today, except for the slight shift to the north, where most business is now conducted along U.S. 380. Not a true ghost town, you still won’t find any trains stopping at the marooned and badly listing depot. Of course, every ghost town aficionado hopes to discover something new, and, while it’s well-known that all that’s left of what could be considered the original Hilton Hotel is its foundation, located across from the old post office (now a restored private residence), I have been unable to find a single picture of the site anywhere. So, as is my wont, I took my own. In fact, I took two. The concrete shown here and below is all that remains of the birthplace of one of the greatest hotel chains in the world, without which Paris Hilton might be living in a trailer out in the Socorro County desert. However, the original ballroom floor from the hotel was reportedly installed in the Wool Warehouse building in Magdalena. It must've been part of a remodeling job as that place was built in 1913. Can anyone get me in to have a look?!

while it’s well-known that all that’s left of what could be considered the original Hilton Hotel is its foundation, located across from the old post office (now a restored private residence), I have been unable to find a single picture of the site anywhere. So, as is my wont, I took my own. In fact, I took two. The concrete shown here and below is all that remains of the birthplace of one of the greatest hotel chains in the world, without which Paris Hilton might be living in a trailer out in the Socorro County desert. However, the original ballroom floor from the hotel was reportedly installed in the Wool Warehouse building in Magdalena. It must've been part of a remodeling job as that place was built in 1913. Can anyone get me in to have a look?!

For those Paris Hilton fans wishing to tour the old ruins, I can be hired at a very reasonable price. Please wear sensible shoes and long pants and don’t expect much.

Info for this post came from Varney and Harris. Special thanks to the grandson of the owners of the San Antonio depot for the quick peak inside. Next time we’ll visit the aforementioned Carthage and Tokay. Or, at least, an area the might as well be.

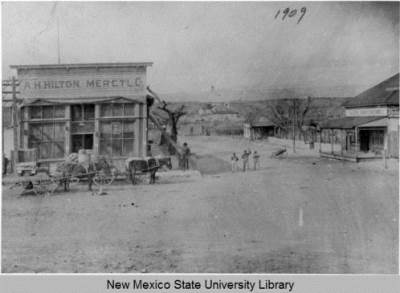

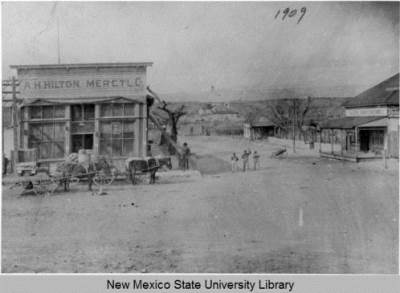

APRIL 2014 UPDATE: Thanks to Jerrysocorro P, a wonderful photo of the A.H. Hilton Merctl Co building has been brought to my attention. Apparently taken in 1909, this is a rare image indeed. It shows the corner on which the above ruins were photographed. Across the street is a building signed as "City Drug Store." This is what was later the post office and still stands as a private residence.

Very interesting to me is the building behind the mercantile. Unfortunately, you can't see it on the downloaded photo, but behind the skeletal tree is a sign on which you can read " OT L". The best way to have a look for yourself is to go to this page. Is this another "Hilton Hotel"? I can't imagine San Antonio supporting two hotels when it couldn't support a bank.

This excellent biography (thanks again, Jerrysocorro P!) on Conrad Hilton mentions a "makeshift hotel" where for $1 you got a room and a hot meal. It also specifically states that there were rooms in the mercantile, although the merc looks rather un-hotel-like. So what is this second apparent hotel? 'Tis a mystery.

Kudos to the University of New Mexico and NMSU for making historical photos like this one available on-line.

located on the east bank of the Rio Grande and close to El Camino Real, was a Spanish agricultural settlement known especially for its grapes. These grapes were crushed into wine reportedly shipped “all the way to Kansas.” The village was also a resting place and trading center for travelers on El Camino Real. Later, some residents became miners and worked in nearby Carthage and Tokay. Apparently, a heated baseball rivalry developed between the San Pedro and Tokay teams with a third forgotten community, Bosquecito, also in the mix.

located on the east bank of the Rio Grande and close to El Camino Real, was a Spanish agricultural settlement known especially for its grapes. These grapes were crushed into wine reportedly shipped “all the way to Kansas.” The village was also a resting place and trading center for travelers on El Camino Real. Later, some residents became miners and worked in nearby Carthage and Tokay. Apparently, a heated baseball rivalry developed between the San Pedro and Tokay teams with a third forgotten community, Bosquecito, also in the mix.

The “clean-up” was ostensibly part of a “desert restoration project” and, while I sure love the desert, I find this a little hard to believe. There is so much wide-open space in every direction out here that restoring this small area strikes me as bizarre. Not impossible though. On the other hand, “Ghost Towns and Mining Camps of New Mexico” stated in 1975: “Today what is left of Carthage is fast melting into oblivion.” Other than the impressive adobe ruins of the large home of a mine superintendent, John Hart, who left Carthage in the mid-1940’s, I have no idea what’s really been lost in the interim. At least the corpse of the small mining car above persists.

The “clean-up” was ostensibly part of a “desert restoration project” and, while I sure love the desert, I find this a little hard to believe. There is so much wide-open space in every direction out here that restoring this small area strikes me as bizarre. Not impossible though. On the other hand, “Ghost Towns and Mining Camps of New Mexico” stated in 1975: “Today what is left of Carthage is fast melting into oblivion.” Other than the impressive adobe ruins of the large home of a mine superintendent, John Hart, who left Carthage in the mid-1940’s, I have no idea what’s really been lost in the interim. At least the corpse of the small mining car above persists.

Then two major floods in 1929 washed away a big chunk of the town and the surrounding farmland. WWII lured away most remaining young men and A.H. Hilton’s original mercantile burnt around the same time, which, incidentally, pretty much coincided with Conrad's marriage to Zsa Zsa Gabor. However, Hilton’s wooden bar was saved and installed in the famous Owl Bar and Restaurant in 1945, where it is used to this day to support Tecate and green chile cheeseburgers. The Owl Bar itself was built by Brunswick Balke Collender Company. You might have used their bowling balls.

Then two major floods in 1929 washed away a big chunk of the town and the surrounding farmland. WWII lured away most remaining young men and A.H. Hilton’s original mercantile burnt around the same time, which, incidentally, pretty much coincided with Conrad's marriage to Zsa Zsa Gabor. However, Hilton’s wooden bar was saved and installed in the famous Owl Bar and Restaurant in 1945, where it is used to this day to support Tecate and green chile cheeseburgers. The Owl Bar itself was built by Brunswick Balke Collender Company. You might have used their bowling balls. while it’s well-known that all that’s left of what could be considered the original Hilton Hotel is its foundation, located across from the old post office (now a restored private residence), I have been unable to find a single picture of the site anywhere. So, as is my wont, I took my own. In fact, I took two. The concrete shown here and below is all that remains of the birthplace of one of the greatest hotel chains in the world, without which Paris Hilton might be living in a trailer out in the Socorro County desert. However, the original ballroom floor from the hotel was reportedly installed in the Wool Warehouse building in Magdalena. It must've been part of a remodeling job as that place was built in 1913. Can anyone get me in to have a look?!

while it’s well-known that all that’s left of what could be considered the original Hilton Hotel is its foundation, located across from the old post office (now a restored private residence), I have been unable to find a single picture of the site anywhere. So, as is my wont, I took my own. In fact, I took two. The concrete shown here and below is all that remains of the birthplace of one of the greatest hotel chains in the world, without which Paris Hilton might be living in a trailer out in the Socorro County desert. However, the original ballroom floor from the hotel was reportedly installed in the Wool Warehouse building in Magdalena. It must've been part of a remodeling job as that place was built in 1913. Can anyone get me in to have a look?!