(CONTINUED) Twenty-Five

I don’t know if Mary slept that night, but I didn’t. Mary had given Julie some prescription pills that should’ve knocked her out for at least eight hours, but when I saw Julie the next morning she looked worse than either Mary or I. She sat down in the dining room and put her head in her hands. Then she looked at Mary. She turned and looked at me and her face crumpled and she began to sob. Mary went back to the bathroom and returned with a pill bottle.

“If this keeps up, give her two of these.”

I took the bottle from Mary. If Julie and I were ever going to get Jimmy back, Julie had to get a hold of herself. As it was, she was in no state to travel, let alone confront what might await us in Arizona. I needed her to get the past the panic on her own, so I was going to do everything I could to make sure I wouldn’t have to use the pills.

Mary left for the gallery and I made Julie a cup of tea and found a box of tissues. The tea grew cold on the table as Julie cried. I asked her a few things about Jimmy--what she thought he might have done, who she thought might have him--but she would only shake her head in reply. Finally, she said, “You can’t come with me.”

“Why not?” I asked.

She sniffed and wiped her nose. “Because there’s no reason why you should.”

“So, you think you can do a better job on your own?”

She started to cry again, but more softly.

“It’s dangerous,” I continued. “Neither of us should be under any illusions about that. I think…”

“But that’s what I mean,” she interrupted. “There’s no reason for you to risk your life. You don’t know me. You don’t know Jimmy. You don’t know anything about us. And I don’t want you to do this.”

I watched Julie rub the tears from her cheeks with the palms of her hands. If she went to Tucson she would never come back. Nor would her brother. And she knew it. “Listen,” I said. “You’re not Captain Ahab asking your crew to sacrifice their lives for something that may exist only in your own mind. You’re right that I don’t know your brother, but I know he’s in trouble and I know he needs help. And I think I do know you.” She started to say something but I continued: “And I’m not going to let you go down there all by yourself. It’s suicide. You know that, don’t you?”

I didn’t expect her to answer and she didn’t. “Maybe we should call the police,” she said.

I thought about this for a few moments. “I don’t know,” I said, finally. “Maybe you’re right. They could be bluffing. But if they’re not, we’re putting Jimmy’s life in danger.” She started to cry again. “Why don’t we go through with the plan for tomorrow and see if we notice anyone following us.” She looked at me strangely. I’d forgotten that Mary and I had not told her about our meager plan.

Twenty-Six

By the time I’d shown Julie the .38 Special she’d be wearing she was sobbing and having difficulty catching her breath. I didn’t think she’d ever be able to use the gun, but there was no reason for her not to carry it. I tried to give her the weapon, but she wouldn’t take it. After a few minutes she’d calmed down and I put the gun in the holster and handed it to her again. “They’ll kill us,” she said. “If they see us with guns they’ll kill us.”

I hefted the 9 mm in my hand. “Maybe not.” I tried to smile. “We might kill them.”

She glared at me, angry and fearful. “I told you I don’t want you to come with me. You can’t be a hero. This isn’t like one of your books.”

“You’re right,” I said. “I can’t be a hero. A hero would be someone that had something to lose.” Then I added: “And there are no heroes in my books. You’d know that if you’d read any of them.” She watched me as I checked the safety lock on the Beretta. “I’ll tell you about my life when this is over,” I said. “But not now.” I wondered if that was true. Would I really tell her? Or did I just figure I’d never have to?

We went back out to the living room, the thick curtain still drawn. It was difficult to tell what time of day it was. We sat on the couch and I asked Julie to tell me anything about Jimmy that might help us--the type of people he associated with, the jobs he’d had, the trouble he’d been in--anything that might give us a clue as to what sort of people we were dealing with. But instead she started talking about when Jimmy was young and her father left and how she’d had to raise her brother by herself.

“I knew Jimmy was going to have a hard time even when he was a baby,” she began. “I was still a kid but I could just tell. I was glad…” She reached for a tissue and wiped her nose. “I was glad my father left before Jimmy had a chance to know him. Jimmy never would’ve made it even this far if my father had been around. I don’t feel any anger toward my dad. I guess I don’t feel anything, really, except gratitude that he went away when he did and never came back. My mother was never any use to Jimmy either. I felt sorry for her but I suppose I’ve always loved her. She embarrassed me. After my dad left she got even worse. I don’t know why. She should’ve felt free.”

I asked her if she’d wanted to raise Jimmy all along. She gave me an odd look that I couldn’t interpret then said, “Yes, I did. Like I said, I knew he was going to be in trouble--he just didn’t seem like he’d fit anywhere--and I thought because I recognized it I could help him. At first I was too young, but by the time I was 11 or so I took over from my mother. I knew there was nobody else that could do it. I tried as hard as I could.” She started to cry again. “And I know he’s tried, too. He’s fought with himself. But it’s like he was cursed.”

“It’s more than just being gay, isn’t it?” Again she looked at me strangely. “It’s not hard to tell,” I offered. “In my line of work it pretty much goes with the territory.”

She shook her head. “No, it’s not all because of that. It’s hardly that at all. Although I knew very early that he was gay. I think girls are better at picking up on that than boys are and, after all, I was his sister. That’s another reason I was glad my father wasn’t around. It would’ve been terrible for Jimmy. My father liked to fight.” She pushed her hair back and began to pick at a spot on the sofa. “I’m not sure if my mother even knows. If she does, she doesn’t say anything about it.”

“Can you tell me what Jimmy’s been into?” I asked again.

She reached for another tissue and dabbed at her eyes. Then she balled it in her fist and squeezed it. “I don’t know. He’s been into a lot of things. At first it was just stealing. Small things. From the grocery store or people’s yards. He didn’t do many drugs then. He drank a lot. He got caught stealing a car and spent some time in a juvenile hall. When he came home he started…” She paused for a moment and took a little breath. “He started working on the street. Going with older men, I guess. He was probably seventeen. Sometimes I didn’t even know where he was living. He really got into drugs around then.” She stopped and I thought she might start crying again, but she didn’t.

“What kind of drugs?” I asked.

“I don’t know. Almost anything, I think. Sometimes he was talking a mile-a-minute and other times he could barely keep his eyes open. I always knew when he was on something. When I saw needle marks on his arms I finally told him he had to do something or I’d call the police. It’s the only time I’ve ever threatened him. He agreed and went into treatment. While he was away I met my ex-husband, Steve, and when Jimmy came out we all lived together for awhile.”

“How did that go?”

She sighed. “Okay at first. Jimmy really seemed to be trying to stay clean. He got a job and paid Steve and I rent though we told him he didn’t have to. Steve was really good about it, too. I thought he might not want Jimmy around, but he was understanding and good to both me and Jimmy. But gradually he started to turn back to the street. He would be gone for days at a time and when he came home it was difficult to talk to him. Steve and I began to fight about what should be done. I wanted to do everything I could for Jimmy. I was his sister. Steve said that Jimmy didn’t want to be helped and I’d just have to face up to that. I knew he might be right, but I couldn’t live like that. I had to keep trying. Eventually Jimmy started stealing from us and one day he took Steve’s watch--it had been his grandfather’s. Jimmy wouldn’t admit to anything and they started fighting. Jimmy was no match for Steve. Steve broke Jimmy’s nose and left that night. We never got the watch back even though Jimmy tried. Or said he tried. I don’t know. Steve came home after a couple days, but it wasn’t the same. I knew if I didn’t forget about Jimmy it would only be a matter of time until Steve left for good. But I couldn’t forget that he’d hurt my brother. I was afraid he was beginning to remind me of my father.” She paused. “I can’t blame Steve for leaving. I think he believed Jimmy would drag us down with him.”

I couldn’t tell her that Steve had been right nor could I tell her that she’d loved her brother more than her husband. She probably already knew these things anyway. So I asked her if she kept in touch with Steve.

“No. I haven’t spoken to him in a couple years. I do think about him sometimes though. I hope he’s happy. I wish things could’ve been different.”

I didn’t bother to ask again about who she thought might have kidnapped her brother. She didn’t know. It was probably drugs. Whether small-time or something more serious I wasn’t sure. It didn’t really matter; either way it was bad. We knew they’d already hurt Jimmy. There was no reason to think they wouldn’t just as easily hurt us. I got up to make us some tea and as I waited for the water to boil I saw the Fed Ex envelope on the kitchen table, a piece of Jimmy’s finger stuck in a plastic baggie. Suddenly I felt sick to my stomach. (CONTINUED)

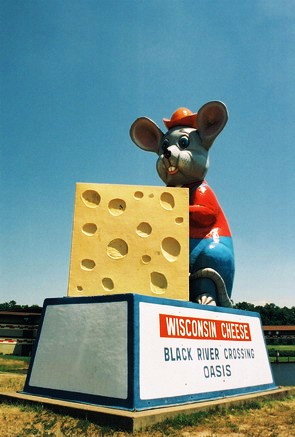

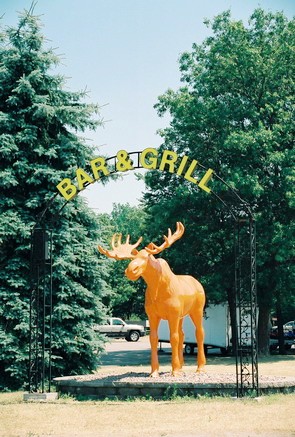

Nothing says fear and gun play better than the state of Wisconsin, and that's where these photos were taken. Four more episodes of A Loss for Words remain.

No comments:

Post a Comment