skip to main |

skip to sidebar

It’s been over eight years since I first wrote about Augusta, Georgia's historic Miller Theater in a post entitled, “Movie Time.” Back then, the Arte Moderne facility, commissioned by Frank J. Miller and designed in 1938 by famed Chicago theater architect Roy Benjamin, had been empty for a couple decades and on the market for years. It appeared accessible, but before we could risk jail time or personal injury we encountered a realtor who saw us taking photos out front and asked if we’d like to have a look inside. Sometimes the easiest way really is the best way, so we took him up on the offer. The theater was huge and ornate, but inside it was cold and dark and hard to get decent photographs. Debris was scattered here and there. Water damage along the walls and ceilings was clearly visible and plaster was crumbling to the floor in places. The realtor said he figured the building could withstand perhaps five more years of vacancy before it would be a total loss.

It’s been over eight years since I first wrote about Augusta, Georgia's historic Miller Theater in a post entitled, “Movie Time.” Back then, the Arte Moderne facility, commissioned by Frank J. Miller and designed in 1938 by famed Chicago theater architect Roy Benjamin, had been empty for a couple decades and on the market for years. It appeared accessible, but before we could risk jail time or personal injury we encountered a realtor who saw us taking photos out front and asked if we’d like to have a look inside. Sometimes the easiest way really is the best way, so we took him up on the offer. The theater was huge and ornate, but inside it was cold and dark and hard to get decent photographs. Debris was scattered here and there. Water damage along the walls and ceilings was clearly visible and plaster was crumbling to the floor in places. The realtor said he figured the building could withstand perhaps five more years of vacancy before it would be a total loss.

That was 2004 and, as of this writing, the Miller Theater is still vacant. However, it has not become a total loss, nor is it still for sale. The building changed hands and was finally purchased by the Miller Theater, LLC, a subsidiary of Symphony Orchestra Augusta. There are big plans for it, including a projected re-opening date during the 2014/2015 season. If you want to read more about the history of the Miller Theater (or about as much as I’ve ever known) you can find my original post HERE.

More recently, I've learned that the building is constructed mostly of concrete and heavy gauge steel reinforcements. Some of the theater’s supporting beams are the largest ever shipped by rail in the state of Georgia. Like I said, the place is big. It was built to hold 1600 seats. Because of this sturdy construction, the structure remains in very good shape. There are still the cosmetic problems I saw in 2004, but apparently nothing that jeopardizes overall integrity or, importantly, would require a massive infusion of cash to fix.

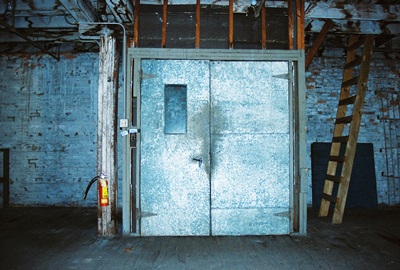

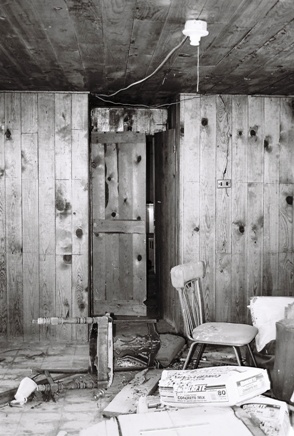

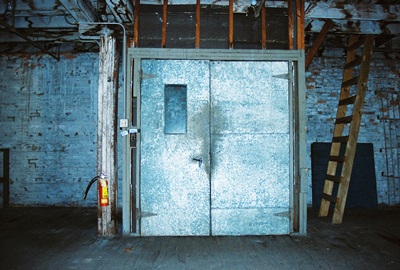

Right now, restoration and renovation is getting underway, but most of the interior of the theater looks pretty much as it did when it shut down thirty years ago. This is especially apparent in the projection booth, where scraps of film litter the floor and the projector itself still sits, perhaps wondering if the day will come when it might return to life. I guess no one has told it that we're in the digital age. Oh well, Katherine Hepburn won’t be coming back for a return visit either. Elsewhere, old signs remain on the doors and ropes hang in the wings.

Right now, restoration and renovation is getting underway, but most of the interior of the theater looks pretty much as it did when it shut down thirty years ago. This is especially apparent in the projection booth, where scraps of film litter the floor and the projector itself still sits, perhaps wondering if the day will come when it might return to life. I guess no one has told it that we're in the digital age. Oh well, Katherine Hepburn won’t be coming back for a return visit either. Elsewhere, old signs remain on the doors and ropes hang in the wings.

Since the Miller Theater was a movie and vaudeville house when it opened in 1940, the stage is a traditional proscenium style and too small for modern performances. It will be enlarged to twice its original size and an orchestra pit that can hold 45 musicians will be created. Eventually, a nine foot polished ebony Steinway grand piano will be brought in. Right now, something a bit more modest can be found. When fully outfitted, it’s said the acoustics will be superior to any other venue in the Central Savannah River Area. At 1325, the seat count will be a little less than the original theater, but still a few hundred more than the 800-seat Imperial Theater on the other side of Broad St.

an orchestra pit that can hold 45 musicians will be created. Eventually, a nine foot polished ebony Steinway grand piano will be brought in. Right now, something a bit more modest can be found. When fully outfitted, it’s said the acoustics will be superior to any other venue in the Central Savannah River Area. At 1325, the seat count will be a little less than the original theater, but still a few hundred more than the 800-seat Imperial Theater on the other side of Broad St.

The Imperial Theater? Yes, Augusta does already have an historic fully restored theater just steps away from the Miller. Designed by the famous architect G. Lloyd Preacher in the Victorian Renaissance style and opened as the Wells Theater in 1917, the Imperial is quite nice indeed. Of course, there has been some commentary about the difficulties Augusta might face in trying to support TWO historic theaters, but surely this shouldn’t be a real problem for the second most populous city in Georgia. Frank Miller once operated five theaters in downtown Augusta alone, including both the Miller and Imperial. In any case, the Miller has real potential and to let it become a “total loss,” as nearly happened, seems pretty much unacceptable.

Symphony Orchestra Augusta is excited about the re-opening of the Miller Theater and they should be. Having also purchased the former Cullum’s building next door, there will be quite a performing arts complex at 7th and Broad St. when everything is finished. The Symphony Board’s stated mission is “to share the joy of great musical performance with our audience.” Those performances can only be enhanced by taking place in a building as soulful as the Miller Theater. “Together, we are music,” is the Board’s tagline. As I recall, Augusta could use some more music, too.

Having also purchased the former Cullum’s building next door, there will be quite a performing arts complex at 7th and Broad St. when everything is finished. The Symphony Board’s stated mission is “to share the joy of great musical performance with our audience.” Those performances can only be enhanced by taking place in a building as soulful as the Miller Theater. “Together, we are music,” is the Board’s tagline. As I recall, Augusta could use some more music, too.

This is the last of four posts on historic buildings visited during the 2012 Augusta Photography Festival. Thanks to the festival and the Miller Theater, LLC for providing ample time and somewhat better lighting to explore the place this go-round. Most information was taken from material provided by Symphony Orchestra Augusta. We'll start 2013 with a quick and much more depressing return visit to the historic Goodale Inn, built in 1799. If fast action is taken there may be hope yet for one of the oldest unaltered buildings in Georgia.

If buildings were ships and fire was ice, then the Marion Building, at 739 Broad St. in Augusta, Georgia, would once have been the Titanic. Designed by G. Lloyd Preacher, who also had a hand in Augusta’s Partridge Inn and Imperial Theater, as well as Atlanta’s famed art-deco, neo-gothic city hall, the Chronicle Building, as it was originally known, was considered to be fireproof. Construction was begun in 1912 and completed in 1914, in what was referred to as “the very teeth of general financial depression.” As Augusta’s first skyscraper, the ten-story Chronicle Building was a big deal.

When it was done, Mr. Preacher himself had this to say in the December 13, 1914 edition of the building's namesake, the Augusta Chronicle: "The Chronicle Building, now ready for occupancy, stands facing the south on Broad Street in a class by itself, distinctive and individual. The building stands ten stories high and possesses all modern conveniences and equipment. It is faced on front with limestone to third floor level, then buff press brick to the eighth story. The two top stories are faced with ornamental polychrome terra cotta in harmonious colors and the entire exterior of the building is trimmed in terra cotta---such as window sills, lintels, etc. All interior floors and partitions are fireproof and the elevator doors, windows on down-town side, etc., are also absolutely fireproof. The first floor lobby is decorated with a high marble wainscoting and plaster cornices. The offices and corridors on the upper floors have smooth finish plaster walls. The corridors all have tile floors and wainscotings of Georgia marble. Ample toilets are provided and they are finished in tile. The trim throughout is genuine oak with veneer doors. The heating system is the best that can be had with a vacuum vapor circulating system. There is enough radiation to overheat the building in zero weather if desired. All floors are provided with vacuum cleaning outlets so that the offices may be perfectly cleaned without dust. Sufficient electric lighting is provided throughout, and every office has a lavatory and an abundance of hot and cold water. There are also two fast elevators, perfectly equipped with indicators, insuring fast service."

The two top stories are faced with ornamental polychrome terra cotta in harmonious colors and the entire exterior of the building is trimmed in terra cotta---such as window sills, lintels, etc. All interior floors and partitions are fireproof and the elevator doors, windows on down-town side, etc., are also absolutely fireproof. The first floor lobby is decorated with a high marble wainscoting and plaster cornices. The offices and corridors on the upper floors have smooth finish plaster walls. The corridors all have tile floors and wainscotings of Georgia marble. Ample toilets are provided and they are finished in tile. The trim throughout is genuine oak with veneer doors. The heating system is the best that can be had with a vacuum vapor circulating system. There is enough radiation to overheat the building in zero weather if desired. All floors are provided with vacuum cleaning outlets so that the offices may be perfectly cleaned without dust. Sufficient electric lighting is provided throughout, and every office has a lavatory and an abundance of hot and cold water. There are also two fast elevators, perfectly equipped with indicators, insuring fast service."

It then must have come as quite a surprise when, just 15 months later, the fireproof Chronicle Building was gutted in Augusta’s worst conflagration, the Great Fire of March 22, 1916, which may have consumed 600 structures and over 20,000 bales of cotton but at least didn’t kill anyone. The fire’s origin was traced to a tailor’s unattended iron. To be fair, no one ever claimed the Chronicle Building was “inferno-proof.” If you want to see an incredible picture of the building in flames on that night, have a look HERE. By 1921, the remains had been purchased by Jacob Phinizy and the Marion Building now stood within the shell of the old, burnt-out structure.

It’s interesting to note that the Marion Building is only half of what it what supposed to be. That is, an identical structure was originally planned to be built to the east of the building. It has yet to materialize.

The Marion Building has now been essentially vacant for over 40 years, with only a tobacconist occupying a small space on the ground floor. Now even he’s gone, as you can see in the picture of the old shop above. It’s a very long while for a building to be empty, I’d say. In 2010, the Marion Building was purchased for $200,000. The inside was then gutted so the building could be “mothballed” in a protected state until such time that the economics of redevelopment become more reasonable. And that is how things stand with Augusta’s first skyscraper as it maintains its long vigil beside the Confederate Monument in the hope its now-modest (but still sunny!) ten stories will one day be of use again.

One, two…this is post number three on buildings visited during this year’s Augusta Photography Festival. The usual thanks to them are in order. Pretty much all the information for this post was taken from the Chronicle’s 2010 article on the Marion, with a little help from the Chronicle’s great photo series on the 1916 fire. Next post I’ll do an update on the Miller Theater, with much better photos than eight years ago. If you’re awaiting a return to the Wild West, a post on the semi-ghost town of Organ, NM, in the shadow of the Organ Mountains, will be forthcoming. Eventually.

Let’s head north out of the Doughty Building, last post’s feature, and pay a visit to its neighbor at 301-303 James Brown Blvd, the Lowrey Wagon Works aka the Confederate Boot Factory. I passed this vacant and unmarked structure at the corner of 9th and Ellis Streets countless times and never gave it a second thought. That was my mistake as the history of this place is fairly fascinating. However, the building is sort of designed to look unassuming. Three stories tall and made of brick, for some reason it was covered in stucco and then scored to look like it was constructed of cinderblock. It’s unassuming alright. And very old. Luckily, Rob Pavey of the Augusta Chronicle did an excellent story on the place in late 2007; most of my information comes from his discussion with Erick Montgomery of Historic Augusta for that piece.

countless times and never gave it a second thought. That was my mistake as the history of this place is fairly fascinating. However, the building is sort of designed to look unassuming. Three stories tall and made of brick, for some reason it was covered in stucco and then scored to look like it was constructed of cinderblock. It’s unassuming alright. And very old. Luckily, Rob Pavey of the Augusta Chronicle did an excellent story on the place in late 2007; most of my information comes from his discussion with Erick Montgomery of Historic Augusta for that piece.

Built in the fall of 1860, initially the building housed the Lowrey Wagon Works only briefly. By April of 1861, with the Civil War beginning, it became a boot factory for the Confederacy. In 1865, after the war, the building was seized by the federal government and given to some local churches to use as a school for freed African-American children. A newspaper noted that the school was "attended by nearly 500 boys and girls" who could "read tolerably well."

The school soon moved to a larger building and, in 1866, J.H. Lowrey returned to his wagon works to make a real go of it for the next 40 years. Lowrey’s red and green wagons were known for their quality and the company claimed they were found “from Viriginia to Mississippi.” “Go on what plantation you will. There, almost as much a part and parcel of the upturned earth of the furrows, there will be found a Lowrey Wagon," read a rather poetic ad in the Augusta Chronicle.

Lowrey did so well that he expanded his manufacturing throughout downtown Augusta and, when he died in 1909, his son, Henry K. Lowrey, took over the company. But, when Henry died in 1925, the business was shuttered. Henry’s grandson and noted Augusta architect, then-90-year-old Lowrey Stulb, told the Chronicle that he visited the wagon works when he was young and saw the wagons being built. "They had a two-horse, a four-horse, and I suppose they made some surreys too," Mr. Stulb said. "The wagons were green and red and had 'Lowrey' painted on the side."

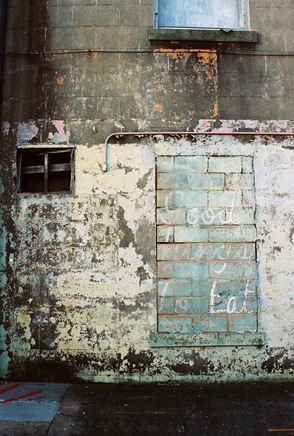

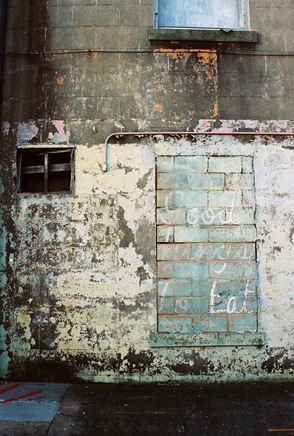

Right after the wagon works shut down, the building was bought by department store magnate J.B. White and used as office space. It also housed a bike shop and, clearly, in one of its last incarnations, a restaurant was on the lower level. There is no indication of its name, although the inscription “Good things to eat” remains on an outside wall. What I don’t have a picture of are the two camera obscurae which have been created by two little holes in the plywood covering the windows of the front doors. While mostly projecting the parking garage across the street, they are still eerily beautiful and, like the now-empty Lowrey Wagon Works building itself, known about by only a very few.

clearly, in one of its last incarnations, a restaurant was on the lower level. There is no indication of its name, although the inscription “Good things to eat” remains on an outside wall. What I don’t have a picture of are the two camera obscurae which have been created by two little holes in the plywood covering the windows of the front doors. While mostly projecting the parking garage across the street, they are still eerily beautiful and, like the now-empty Lowrey Wagon Works building itself, known about by only a very few.

Thanks to Historic Augusta and the 2012 Augusta Photography Festival for providing access.

Next we’ll visit the fireproof building that was gutted by fire less than two years after its initial construction. Yup, that would be the Marion Building.

Let’s start our trip back to Augusta, Georgia at the intersection of two of my favorite streets, Ellis and James Brown Blvd (aka 9th St.). In ’03 and ’04 I used to wander around this area a lot and I took many photographs. Later, I did entire posts on Ellis St. and JB Blvd. Ellis St. has got to be cool if Dinosaur Jr. shot the first part of their video for Over It there. At the time, I didn’t know much about the history of the buildings I was visiting. For many of them, this is still the case. But, with the help of Historic Augusta, this year’s Augusta Photography Festival got access to one that I passed many times, so now I know at least a little something about it. One of the things I know is that it’s got some great fireplaces. The two featured at the top and bottom of this post were up on the second floor. Those are the original mantels, too.

This building, at 307 James Brown Blvd, just south of Ellis, we'll call the Doughty Building since the three-and-a-half story Second Empire style structure was built by Dr. William H. Doughty, Sr. as an investment property between 1884 and 1890. Yup, it’s old. And it's on the National Register of Historic Places. Dr. Doughty’s son, William Jr., was Dean of the Medical College of Georgia from 1910-1923. His tenure ended suddenly when he died from an infection following a tooth extraction. I’m not sure if there’s irony to be found there or not. But I digress. The building was originally intended to be a commercial townhouse but by the late 1800’s it was a Chinese laundry operated by Sang Sing and Sang Lee. Clothes were washed into the 1900’s and then, in 1917, the building was bought by Mrs. Ellen J. Doremus, the daughter of former Augusta Mayor Charles Estes. Mrs. Doremus paid $8000 for the place and the lower level, at least, remained mostly commercial space. Now part of the first floor is home to a furniture refinishing shop but most of the rest of the building is vacant and just waiting for someone to come along and give it a helping hand. There's what appears to be about 120 years worth of wallpaper at the foot of these entryway stairs.

I’m not sure if there’s irony to be found there or not. But I digress. The building was originally intended to be a commercial townhouse but by the late 1800’s it was a Chinese laundry operated by Sang Sing and Sang Lee. Clothes were washed into the 1900’s and then, in 1917, the building was bought by Mrs. Ellen J. Doremus, the daughter of former Augusta Mayor Charles Estes. Mrs. Doremus paid $8000 for the place and the lower level, at least, remained mostly commercial space. Now part of the first floor is home to a furniture refinishing shop but most of the rest of the building is vacant and just waiting for someone to come along and give it a helping hand. There's what appears to be about 120 years worth of wallpaper at the foot of these entryway stairs.

If perhaps you'd like to purchase this building (now at $59,900), Historic Augusta's listing is a good place to start. There is a preservation easement on the property, so at least it's got some protection. Besides Historic Augusta's webpage, I got a lot of information for this post from material they originally put together for a loft tour and which was used again during our visit. I learned about Dr. William Doughty, Jr.’s tragic fate from the Medical College of Georgia’s old website.

The next post will be on the Doughty Building’s neighbor at 301 James Brown Blvd (you can see a little of it at the right in the color photo above), the Lowrey Wagon Works aka the Confederate Boot Factory. So, yes, this one will be pre-Civil War.

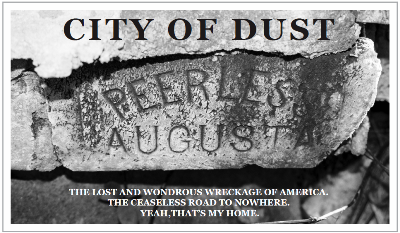

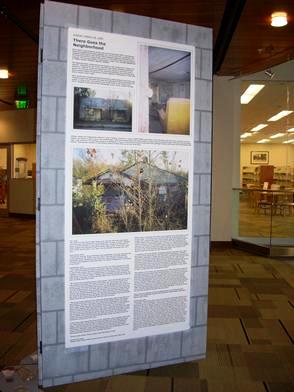

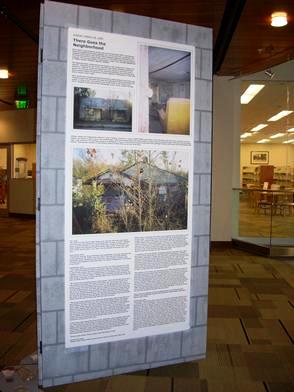

I’m just back from the 2012 Augusta Photography Festival in Augusta, Georgia. This visit back to the place where I first conceived of City of Dust, and the related exhibit which I was at least partially there to promote, are the best things that have ever happened as a result of my photography and attendant attempts at historical documentation. And it was all because of this website. So, let’s hear it for the internet. It does occasionally produce results that would not be possible otherwise. I still recommend being wary of it though. You never know what you might find or how much time it will cost you.

Anyway, the City of Dust exhibit has had its run at the Augusta Public Library extended until at least November 14th. Three sets of three Stonehenge-sized panels occupy space beside the stairway on all three floors of the Main Branch at 823 Telfair Street. Walk right in the front door and you can’t miss ‘em. This beautiful new library is right off James Brown Boulevard, which I used to explore when it was considerably more desolate.

Once the exhibit closes at the library, it will move over to the Aiken County Historical Museum in South Carolina. This is very exciting. It certainly beats having the panels cut-up for fire wood since they’re too big to store in even a good-sized garage. The exhibit might be available for viewing at the museum as early as December 3rd. The Aiken Historical Museum occupies a 1930’s-era mansion named “Banksia” and it’s at 433 Newberry St. SW in Aiken. Like the library, admission is free, but why not become a member? Tell them City of Dust sent you!

In the spirit of the exhibit, the festival offered two excellent photo safaris to some historic buildings in downtown Augusta. One, the Miller Theater, City of Dust has visited before. But this time I got better photos. The other sites were the Marion and Doughty Buildings and the Lowrey Wagon Works/Confederate Boot Factory, none of which I had anything close to access to previously. As after my last trip in 2010, when I stopped by James Brown’s old neighborhood and dug up some information on the Palace Theater, the next few posts will document the places I photographed while back in Georgia. In addition to the safari buildings, I found a few new out-of-the-way spots and checked-out what remained of some old favorites, like that house above in the Harrisburg neighborhood. Yes, it looks worse now. I also learned a few things. See that brick at the top? I really knew nothing about the factory from which it came, even though I did a whole post on the place years ago. Now, a lecture attendee has told me it was probably the Hankinson and Haugh factory. And the old freezer facility on Walker St. that was torn down? It was owned by Swift and burned in a fire started by homeless people in which one person died. Anyway, like in the old days I hope to do this series of posts quickly, in contrast to my current once-per-month-if-I’m-lucky pace. So, stay tuned and we’ll get started shortly.

the next few posts will document the places I photographed while back in Georgia. In addition to the safari buildings, I found a few new out-of-the-way spots and checked-out what remained of some old favorites, like that house above in the Harrisburg neighborhood. Yes, it looks worse now. I also learned a few things. See that brick at the top? I really knew nothing about the factory from which it came, even though I did a whole post on the place years ago. Now, a lecture attendee has told me it was probably the Hankinson and Haugh factory. And the old freezer facility on Walker St. that was torn down? It was owned by Swift and burned in a fire started by homeless people in which one person died. Anyway, like in the old days I hope to do this series of posts quickly, in contrast to my current once-per-month-if-I’m-lucky pace. So, stay tuned and we’ll get started shortly.

Thanks to Tricia and Peter Hughes for all their hard work and dedication to construction and promotion. Thanks also to the Augusta Public Library, the Friends of the Library, the Augusta Photography Festival and Rebecca Rogers, and Verge Magazine and Mary Bordeaux for publishing many fine articles in advance of the festival. Also, thanks to the Aiken County Historical Museum for offering to host the exhibit next month. Finally, thanks to Lowe’s for donating the material used to make the panels themselves. Many thanks everyone!

We’re gonna leave New Mexico for a bit and head into southern Colorado. It’s interesting, because as soon as you enter Colorado you know you’re in a different place. The same is true of Arizona. I find it hard to believe that the surveyors that marked out state boundaries across the West based them largely on landscape, but southern Colorado is definitely not New Mexico. Colorado also has its own thing going when it comes to what we check out here at City of Dust. So, let’s have a look at Colorado State Highway 12, also known as the Highway of Legends and considered to traverse some of the finest mountain countryside in the U.S. But note that this is only the southeastern portion of the Scenic Byway, through the Purgatoire (“picketwire” if you're an English fur trapper) River Valley. On this visit, time constraints prevented a full circuit north through the Cuchara Pass and on into La Veta. Bummer.

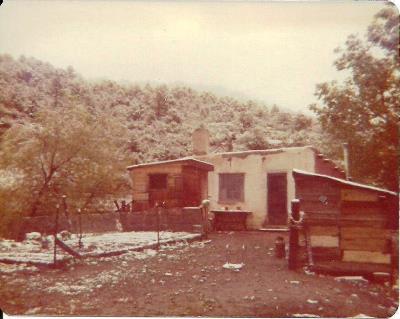

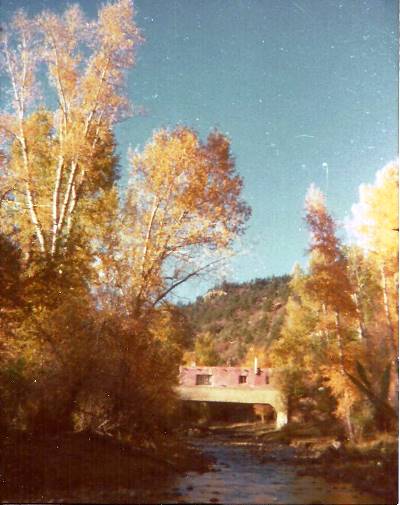

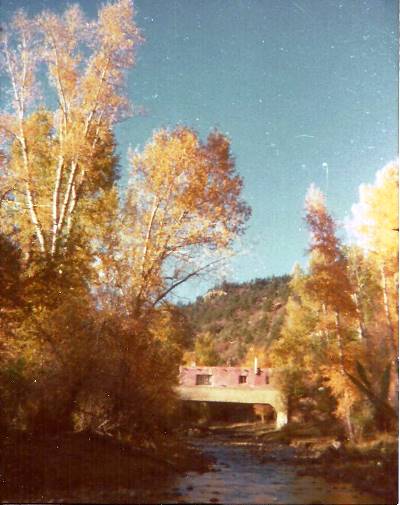

Generally, I think people drive the Highway of Legends heading west out of Trinidad, but we’re going to run it backwards, starting at what has been called the most-photographed and most-painted house in Las Animas County, the House on the Bridge in Vigil. I guess I’ll add a few more shots to the tally. The town of Vigil was settled by Juan Vigil in the 1860’s and incorporated in 1890. The post office operated until 1920, but not much has been going on since then. In 1918, the original road east from Vigil to Stonewall was re-routed and a small bridge over the North Fork of the Purgatoire River was orphaned. Joseph E. Martinez, a state senator, was half-brother to Charles Vigil, the property owner, and built a little house on the bridge. Marcus Vigil, Charles’ brother, rebuilt the house at some point and that’s what remains now. It’s very quaint and must’ve been a nice place to live, with the burbling river (um, maybe "creek" is a better term now) below and mountains all around. There aren’t many neighbors either. That's it in the two photos above.

Heading east we arrive shortly at Weston, originally known as Los Sisneros after Juan Sisneros, a rancher who settled in the area in the 1880’s. A post office was built in 1889 and the town was renamed after the postmaster, Bert Weston. At the turn of the 20th Century, Weston was the supply base for the Rocky Mountain Timber Company. Currently, there’s an abandoned general store. But the North and South Forks of the Purgatoire River meet here and the majestic Sangre de Cristo Mountains loom in the distance. The name, translated as “Blood of Christ,” comes from Spanish explorers who saw that the morning sun turned the peaks red. There’s a story about a prospector who came to town out of the Sangre de Cristo’s once a year with a large nugget with which he bought supplies for another full year. The prospector said that he used the red morning light to find his mine high up along the tree line. When he died without revealing the mine’s location, many men tried fruitlessly to find “gold where the snow turns to blood.”

Throughout the Purgatoire Valley are numerous old churches. The one above is in Segundo, an old coal mining town. Segundo was founded about 1900 and the Colorado and Wyoming railroad made its operating headquarters here in 1901, constructing a five-stall roundhouse. At one point, Segundo processed more coal than anyplace west of Chicago, claiming 800 ovens in which moisture, sulfur, and phosphorus were burned off to make coke, which was especially desirable for smelting. Now it's delightfully deserted, relatively speaking.

Coal was a pretty big deal in the Purgatoire Valley, near the mouth of which sits the aptly-named Cokedale. Founded in 1907 by the American Smelting and Refining Company (ASRC), by 1909 Cokedale had a population of 1,500 and 350 coking ovens. In 1947, the ASRC shut down and company houses were sold to residents for $100 per room and $50 per lot. Because many residents purchased their homes (and despite many houses being bulldozed), Cokedale is considered the best preserved coal mining camp in Colorado and is on the National Register of Historic Places. Across from the rows of old ovens outside of town, steam still rises from slag heaps, the last bit of mining activity that remains.

From Cokedale it’s just a few miles back to a good meal in Trinidad, which is worthy of its own post. But whether it will be the NEXT post I haven’t quite decided.

Information for this post was swiped from Sangres.com and Trinidadco.com.

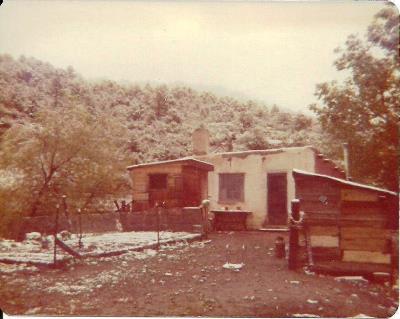

OCTOBER 2013 UPDATE: Sometimes people contact me personally and their recollections are so interesting that I ask if I can post their stories directly on City of Dust. This time, Mandy W. has graciously agreed to let me pass along both her memories of growing up for several years in the House on the Bridge--also known as Bridgehouse, apparently--AND some great vintage photos circa 1974:

"I just read your piece on the Bridgehouse near Weston, CO. I lived there from ages 4-10, then we moved up Wet Canyon to a house my dad built up there. We went to school at Weston Elementary, which is now closed. Thank you for your history. We mostly only knew it as our childhood home, and had a difficult time sleeping once we moved up the Canyon because we no longer had our River to put us to sleep! It was a magical and difficult place to live..."

It's one of the best and strangest powers of the internet that I can post about an odd and fascinating abandoned house in rural southern Colorado and somebody who lived there can find the piece and send me their own photos and recollections. Very cool. Thanks again, Mandy.

FEBRUARY 2014 UPDATE: Mandy W. has come through again with more information regarding the construction of Bridgehouse, where her family lived for a few years in the 1970's. Her dad filled in some of the story. I've never seen the construction dates elsewhere.

"Bridgehouse was built in 1941 in two stages. The highway used to go up by Vigil, but was moved to where it currently runs (Highway 12). The bridge itself was built in 1918. My dad rented it from 1971-1977 for $50/month but worked off the rent! He's not sure if anyone else lived in it besides an artist who was there prior to us."

Many thanks to Mandy for filling in some more of the history of her old home.

APRIL 2014 UPDATE: Below is another piece of Bridgehouse history, kindly submitted by V.J.A.

"After reading everything you posted about Bridgehouse, I just have to add what I know to the story. Around 1966/1967 my great grandparents, Bacilio and Mary Garcia, lived in the house. Like Mandy's father, Grandpa Bacilio was also a ranch hand for the property owner. Although they only lived there for a year or so my mother-in-law, Lena Guzman, has memories of playing in the creek under the bridge.

"It's not much but it at least adds to the timeline."

And so it does! Thanks very much, V.J.

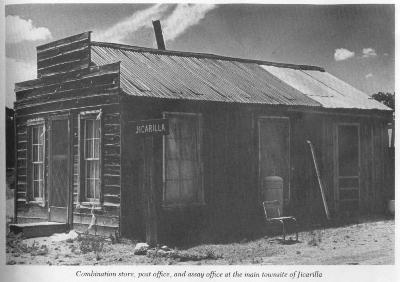

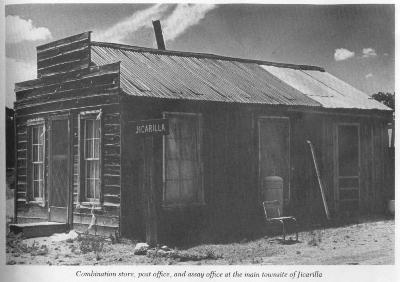

About seven miles south of Ancho, down an unexpectedly bumpy gravel county road (I’ve gotta learn to pay better attention to map symbols), is what remains of Jicarilla. Named for the surrounding Jicarilla Mountains (jicarilla is Spanish for “little basket” or “little gourd”) and, by extension, the Jicarilla Apache, gold first started being pulled out of the area prior to the 1820’s. This is when the Spanish, followed by the Mexicans, came with pans and wooden bowls called “bateas” to work the creeks. Although, truth be told, it was often Native American slaves that did the actual work. In 1864, the U.S. Army forced the local Apache onto distant reservations. By then, Texans had been drifting in and trying their luck for over 20 years. Prospectors arrived en masse in the 1880’s and by 1892 Jicarilla had a post office, which also served as an assay office and store. That's it pictured above. At this time, about 200 people lived in Jicarilla and by 1900 a saloon had opened and the town had a Justice of the Peace.

It was during the Great Depression that the population of Jicarilla peaked at around 300, when desperate people tried to support themselves by gold mining. Actually, I think that kind of thing is happening around the country again right now. Mining could bring in as much as $7 per day and there was plenty of game to provide extra food. But Jicarilla must’ve been a little too remote for most folks as nearly everyone left once the economy improved. By 1942, Jicarilla was pretty much done.

However, some mining continued until relatively recently, when the Lincoln National Forest, which borders Jicarilla, decided to crack down on miners who lived or worked on federal land.

About seven miles south of Ancho, down an unexpectedly bumpy gravel county road (I’ve gotta learn to pay better attention to map symbols), is what remains of Jicarilla. Named for the surrounding Jicarilla Mountains (jicarilla is Spanish for “little basket” or “little gourd”) and, by extension, the Jicarilla Apache, gold first started being pulled out of the area prior to the 1820’s. This is when the Spanish, followed by the Mexicans, came with pans and wooden bowls called “bateas” to work the creeks. Although, truth be told, it was often Native American slaves that did the actual work. In 1864, the U.S. Army forced the local Apache onto distant reservations. By then, Texans had been drifting in and trying their luck for over 20 years. Prospectors arrived en masse in the 1880’s and by 1892 Jicarilla had a post office, which also served as an assay office and store. That's it pictured above. At this time, about 200 people lived in Jicarilla and by 1900 a saloon had opened and the town had a Justice of the Peace.

It was during the Great Depression that the population of Jicarilla peaked at around 300, when desperate people tried to support themselves by gold mining. Actually, I think that kind of thing is happening around the country again right now. Mining could bring in as much as $7 per day and there was plenty of game to provide extra food. But Jicarilla must’ve been a little too remote for most folks as nearly everyone left once the economy improved. By 1942, Jicarilla was pretty much done.

However, some mining continued until relatively recently, when the Lincoln National Forest, which borders Jicarilla, decided to crack down on miners who lived or worked on federal land.  I’ve been told that this was at least partially a result of miners dumping waste in the forest. Whatever the case, the last miner in the area was a man named Jerry Fennell, who had spent 30 years working his claim, finding a little gold here and there, and living in what had been Jicarilla’s general store until one day he was required to submit an official plan of operation. Unable to pay the reclamation bond, Mr. Fennell and Dusty, his well-named burro, shut everything down in the early 2000’s, the last in a line of miners stretching back to the Jicarilla and Mescalero Apaches, who extracted turquoise from the mountains in the late 1500’s.

I’ve been told that this was at least partially a result of miners dumping waste in the forest. Whatever the case, the last miner in the area was a man named Jerry Fennell, who had spent 30 years working his claim, finding a little gold here and there, and living in what had been Jicarilla’s general store until one day he was required to submit an official plan of operation. Unable to pay the reclamation bond, Mr. Fennell and Dusty, his well-named burro, shut everything down in the early 2000’s, the last in a line of miners stretching back to the Jicarilla and Mescalero Apaches, who extracted turquoise from the mountains in the late 1500’s.

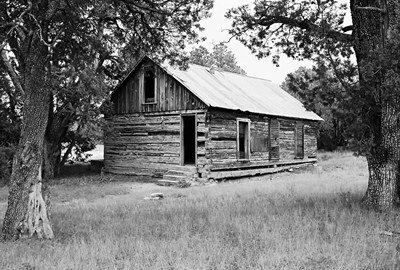

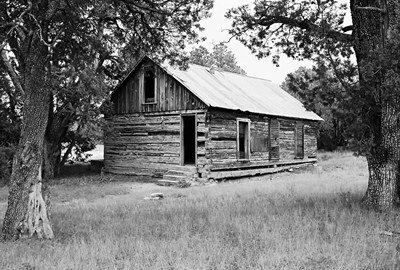

Almost a mile to the south is the log schoolhouse above, built in 1907. Also functioning as a church and general meeting place, it was used through the Depression. The fellow from White Oaks that I mentioned in the LAST POST recalled going to dances in the schoolhouse. He was also at Normandy and told us some harrowing tales of storming the beach. I may say more about him when I finally do a post on White Oaks.

Almost a mile to the south is the log schoolhouse above, built in 1907. Also functioning as a church and general meeting place, it was used through the Depression. The fellow from White Oaks that I mentioned in the LAST POST recalled going to dances in the schoolhouse. He was also at Normandy and told us some harrowing tales of storming the beach. I may say more about him when I finally do a post on White Oaks.

During our visit there appeared to have been some recent activity around a more modern-looking green cabin on the east side of the road. This place is known as the "Hunt Casita," after a family that lived there in the late 1970's. But the post office, small adobe general store (not pictured), and schoolhouse are entirely quiet, as is most of the area around Jicarilla these days. Above is a photo from Philip Varney of the post office looking quite a bit better than it does now, circa maybe 1980.

I got some information for this post from Legends of America. The story of Jicarilla’s last miner (and a good chronology of area mining) can be found HERE. A relative of the Hunt's (and friend of Jerry Fennell) provided a little extra detail. Of course, I grabbed a bit of background and general inspiration from Philip Varney.

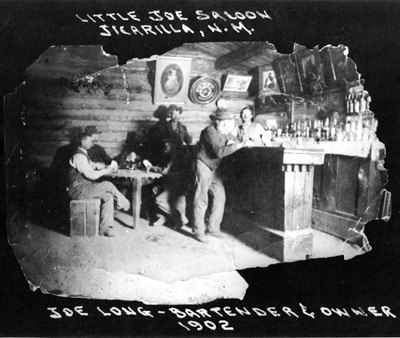

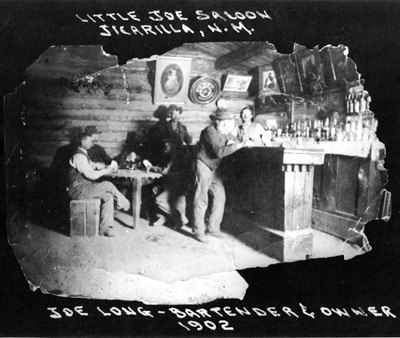

JUNE 2015 UPDATE: I received a photo circa 1902 of the Little Joe Saloon, which is almost surely the same saloon I refer to above as opening in 1900. It is a wonderful shot submitted by the great-grandson and namesake of the saloon's original owner, Joe Long, who lived with his wife Viola in Jicarilla in the early 1900's. Another relative left a comment below about Mr. Long which says that Joe "gave up" the saloon for cattle ranching when his daughter was born in 1908. Apparently Joe and Viola then went on to have 11 more children.

Many thanks to Mr. Long for passing along a fantastic piece of family history which just happens to also be ghost town history.

During our visit there appeared to have been some recent activity around a more modern-looking green cabin on the east side of the road. This place is known as the "Hunt Casita," after a family that lived there in the late 1970's. But the post office, small adobe general store (not pictured), and schoolhouse are entirely quiet, as is most of the area around Jicarilla these days. Above is a photo from Philip Varney of the post office looking quite a bit better than it does now, circa maybe 1980.

I got some information for this post from Legends of America. The story of Jicarilla’s last miner (and a good chronology of area mining) can be found HERE. A relative of the Hunt's (and friend of Jerry Fennell) provided a little extra detail. Of course, I grabbed a bit of background and general inspiration from Philip Varney.

JUNE 2015 UPDATE: I received a photo circa 1902 of the Little Joe Saloon, which is almost surely the same saloon I refer to above as opening in 1900. It is a wonderful shot submitted by the great-grandson and namesake of the saloon's original owner, Joe Long, who lived with his wife Viola in Jicarilla in the early 1900's. Another relative left a comment below about Mr. Long which says that Joe "gave up" the saloon for cattle ranching when his daughter was born in 1908. Apparently Joe and Viola then went on to have 11 more children.

Many thanks to Mr. Long for passing along a fantastic piece of family history which just happens to also be ghost town history.

Lincoln County, New Mexico is Billy the Kid country. The Kid gained his reputation in the Lincoln County War of 1878 and escaped the hangman’s noose by shooting his jailer’s in the Lincoln County Courthouse. I may do an entire post on Billy the Kid and the town of Lincoln someday, but right now we’re going to visit Ancho, in the northwestern part of Lincoln County.

Ancho (pronounced like the first part of “anchovie”) is Spanish for “wide” or “broad” and refers to the valley in which the town sits. Most towns in New Mexico were born by the railroad or minerals and Ancho owes its existence to both. The El Paso and Northeastern Railroad pushed into the valley around 1900 and designated that there be a stop in the vicinity. Within a year, a gypsum deposit was discovered not far away and a plaster mill was built, operated by the Gypsum Product Company. In 1902 (or 1905, depending on your source), a proper railroad depot was put up and some company houses constructed. In 1905, the Ancho Brick Company was created to utilize the abundant fire clay in the area.

Lincoln County, New Mexico is Billy the Kid country. The Kid gained his reputation in the Lincoln County War of 1878 and escaped the hangman’s noose by shooting his jailer’s in the Lincoln County Courthouse. I may do an entire post on Billy the Kid and the town of Lincoln someday, but right now we’re going to visit Ancho, in the northwestern part of Lincoln County.

Ancho (pronounced like the first part of “anchovie”) is Spanish for “wide” or “broad” and refers to the valley in which the town sits. Most towns in New Mexico were born by the railroad or minerals and Ancho owes its existence to both. The El Paso and Northeastern Railroad pushed into the valley around 1900 and designated that there be a stop in the vicinity. Within a year, a gypsum deposit was discovered not far away and a plaster mill was built, operated by the Gypsum Product Company. In 1902 (or 1905, depending on your source), a proper railroad depot was put up and some company houses constructed. In 1905, the Ancho Brick Company was created to utilize the abundant fire clay in the area.

For a time, the heart of Ancho was made of plaster and brick. Ancho-made bricks and plaster helped rebuild San Francisco after the 1906 'quake and more bricks were used for smelter stacks in Arizona. In 1930, the town used its own product to construct a large, brick schoolhouse, replacing the small, wooden, one-room job that burnt down. The school had as many as five teachers and 140 students. However, Ancho was in trouble. Phelps Dodge had purchased the brick plant in 1917, enlarged it, and then shut it down following bankruptcy in 1921. It was finally dismantled in 1937 by the Abilene Salvage Company. There was a slight increase in population during the Depression as desperate families tried to make money mining for gold in the Jicarilla Mountains, but that was short-lived. In 1954, U.S. 54 was laid out, cutting Ancho off by over 2 miles on the route between Corona and Carrizozo. The school closed the following year. In 1959, the railroad shuttered the depot (photos at top and below) and the final nail was put in Ancho’s coffin. Almost.

For a time, the heart of Ancho was made of plaster and brick. Ancho-made bricks and plaster helped rebuild San Francisco after the 1906 'quake and more bricks were used for smelter stacks in Arizona. In 1930, the town used its own product to construct a large, brick schoolhouse, replacing the small, wooden, one-room job that burnt down. The school had as many as five teachers and 140 students. However, Ancho was in trouble. Phelps Dodge had purchased the brick plant in 1917, enlarged it, and then shut it down following bankruptcy in 1921. It was finally dismantled in 1937 by the Abilene Salvage Company. There was a slight increase in population during the Depression as desperate families tried to make money mining for gold in the Jicarilla Mountains, but that was short-lived. In 1954, U.S. 54 was laid out, cutting Ancho off by over 2 miles on the route between Corona and Carrizozo. The school closed the following year. In 1959, the railroad shuttered the depot (photos at top and below) and the final nail was put in Ancho’s coffin. Almost.

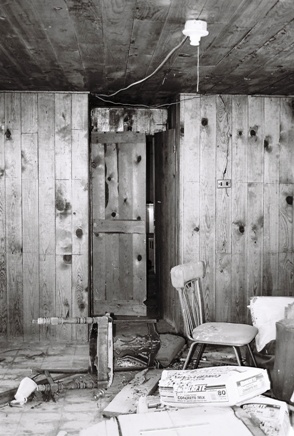

In 1963, Mrs. Jackie Silvers purchased the old depot, somehow moved it off the railroad right-of-way, and then filled it with all manner of antiques from the area. My House of Old Things, as the “museum” was called, got a rave review in Varney’s New Mexico ghost town book. He called it “a wonderful conglomeration of all the things you thought nobody had saved” and said it was “not to be overlooked.” But Varney’s book is over 30 years old and so we didn’t get our hopes up. This was good because, while it was still easy to find My House of Old Things, it was immediately clear that it was very closed and had been for years. A disappointing reversal of our fortunes in Chloride. A still-furnished cabin nearby hints at what used to be on display.

In 1963, Mrs. Jackie Silvers purchased the old depot, somehow moved it off the railroad right-of-way, and then filled it with all manner of antiques from the area. My House of Old Things, as the “museum” was called, got a rave review in Varney’s New Mexico ghost town book. He called it “a wonderful conglomeration of all the things you thought nobody had saved” and said it was “not to be overlooked.” But Varney’s book is over 30 years old and so we didn’t get our hopes up. This was good because, while it was still easy to find My House of Old Things, it was immediately clear that it was very closed and had been for years. A disappointing reversal of our fortunes in Chloride. A still-furnished cabin nearby hints at what used to be on display.

Later, in nearby White Oaks, we met a man born in Ancho. It was revealed that Mrs. Sara Jackson, who’d taken over the house when Jackie, her mother, died, passed away several years ago. Her family had expressed no interest whatsoever in maintaining the house or its old things. Apparently many items were sold on EBAY, which we were told was

Later, in nearby White Oaks, we met a man born in Ancho. It was revealed that Mrs. Sara Jackson, who’d taken over the house when Jackie, her mother, died, passed away several years ago. Her family had expressed no interest whatsoever in maintaining the house or its old things. Apparently many items were sold on EBAY, which we were told was “heartbreaking” given their relation to the history of ranching, farming, and homemaking in the region. Who knows what was sold, but peeping inside it appeared that much remains. Furniture, clothes, an old wooden letter box. Through one window was a mannequin head, seemingly presiding over the dust and decay, waiting for something to finally happen. It may be a long wait. The old playground, abandoned over 50 years ago, still stands, made of bolts and bits of pipe that no school would allow children to play on in this day and age. The school, pictured below, seems to have fared better and is now a church. Though who attends I have no idea.

“heartbreaking” given their relation to the history of ranching, farming, and homemaking in the region. Who knows what was sold, but peeping inside it appeared that much remains. Furniture, clothes, an old wooden letter box. Through one window was a mannequin head, seemingly presiding over the dust and decay, waiting for something to finally happen. It may be a long wait. The old playground, abandoned over 50 years ago, still stands, made of bolts and bits of pipe that no school would allow children to play on in this day and age. The school, pictured below, seems to have fared better and is now a church. Though who attends I have no idea.

Not one car passed down the road during our visit. The town was completely silent. Lightning flashed on the horizon and for a brief moment a few big drops of rain fell. Only one building seemed occupied and, indeed, we learned that someone does live there. So, this is Ancho in 2012, population 1.

As so often happens, most of the info for this post came from Philip Varney's ghost town book, but Legends of America fleshed out some details.

Not one car passed down the road during our visit. The town was completely silent. Lightning flashed on the horizon and for a brief moment a few big drops of rain fell. Only one building seemed occupied and, indeed, we learned that someone does live there. So, this is Ancho in 2012, population 1.

As so often happens, most of the info for this post came from Philip Varney's ghost town book, but Legends of America fleshed out some details.

A few weeks ago we visited an unusual house on a hillside nestled deep in the barren wilderness of Socorro County, New Mexico. A hippy pad in the middle of nowhere or the most eccentrically outfitted ranch house ever built...who's to say? For this post we'll stay in Socorro County but check out a place that makes a lot more sense: the Old Stapleton Ranch.

True to its name, the Old Stapleton Ranch was clearly once just that--a working ranch.

A few weeks ago we visited an unusual house on a hillside nestled deep in the barren wilderness of Socorro County, New Mexico. A hippy pad in the middle of nowhere or the most eccentrically outfitted ranch house ever built...who's to say? For this post we'll stay in Socorro County but check out a place that makes a lot more sense: the Old Stapleton Ranch.

True to its name, the Old Stapleton Ranch was clearly once just that--a working ranch.  In fact, the place still attracts cattle and on the day we visited they were milling all around, lowing and looking alternately angry and confused by our presence. The noise actually made it hard to concentrate on exploring. Thankfully, they eventually got bored and wandered off into the desert somewhere. Exactly when the ranch might have been abandoned I have no idea, but I'd say it's been empty for a few decades now. There are still some canned goods in the kitchen, but I wouldn't eat them if I were you.

Adjacent to the ranch is a holding pen and a water tank, so the cattle weren't there for nothing. Apparently some ranchers must still be using the site to hold livestock, but it didn't look like the house had been entered in quite some time.

In fact, the place still attracts cattle and on the day we visited they were milling all around, lowing and looking alternately angry and confused by our presence. The noise actually made it hard to concentrate on exploring. Thankfully, they eventually got bored and wandered off into the desert somewhere. Exactly when the ranch might have been abandoned I have no idea, but I'd say it's been empty for a few decades now. There are still some canned goods in the kitchen, but I wouldn't eat them if I were you.

Adjacent to the ranch is a holding pen and a water tank, so the cattle weren't there for nothing. Apparently some ranchers must still be using the site to hold livestock, but it didn't look like the house had been entered in quite some time.

The 1940 Chevrolet truck out front and the whitened branches of dead trees provided appropriate atmosphere, as did the name of the valley in which the ranch is located. Valle del Ojo de la Parida could translate as "Valley of the Spring of Nonsense (or Stupidity)," which leads me to believe that someone went looking for water nearby and didn't find it. Or the water made them crazy. It could also be something like "Valley of the Spring of the Young Mother." Frankly, I'm not sure I'd want to be a young mother way out here. While the name certainly refers to a spring, I do like the idea that "ojo" could translate as "eye." There's just something about wandering around in the "Valley of the Eye of Nonsense" that appeals to me. At least until I collapse from dehydration.

The 1940 Chevrolet truck out front and the whitened branches of dead trees provided appropriate atmosphere, as did the name of the valley in which the ranch is located. Valle del Ojo de la Parida could translate as "Valley of the Spring of Nonsense (or Stupidity)," which leads me to believe that someone went looking for water nearby and didn't find it. Or the water made them crazy. It could also be something like "Valley of the Spring of the Young Mother." Frankly, I'm not sure I'd want to be a young mother way out here. While the name certainly refers to a spring, I do like the idea that "ojo" could translate as "eye." There's just something about wandering around in the "Valley of the Eye of Nonsense" that appeals to me. At least until I collapse from dehydration.

The only other thing I could learn about this area is that there used to be a fair amount of mining going on. Oh, and there’s a lot of the mineral thomsonite lying around. Otherwise, the whole area is pretty much shrouded in mystery as far as Google is concerned.

Alright, that's all I've got for this one. Next time we'll go to Ancho, which is one house away from being a true ghost town. Years ago Ancho would've been a find not unlike Chloride, but that time has passed and much history is now slowly rotting away out there in central New Mexico. At least what wasn't sold on EBAY. Seriously. Stay tuned.

The only other thing I could learn about this area is that there used to be a fair amount of mining going on. Oh, and there’s a lot of the mineral thomsonite lying around. Otherwise, the whole area is pretty much shrouded in mystery as far as Google is concerned.

Alright, that's all I've got for this one. Next time we'll go to Ancho, which is one house away from being a true ghost town. Years ago Ancho would've been a find not unlike Chloride, but that time has passed and much history is now slowly rotting away out there in central New Mexico. At least what wasn't sold on EBAY. Seriously. Stay tuned.

It’s been over eight years since I first wrote about Augusta, Georgia's historic Miller Theater in a post entitled, “Movie Time.” Back then, the Arte Moderne facility, commissioned by Frank J. Miller and designed in 1938 by famed Chicago theater architect Roy Benjamin, had been empty for a couple decades and on the market for years. It appeared accessible, but before we could risk jail time or personal injury we encountered a realtor who saw us taking photos out front and asked if we’d like to have a look inside. Sometimes the easiest way really is the best way, so we took him up on the offer. The theater was huge and ornate, but inside it was cold and dark and hard to get decent photographs. Debris was scattered here and there. Water damage along the walls and ceilings was clearly visible and plaster was crumbling to the floor in places. The realtor said he figured the building could withstand perhaps five more years of vacancy before it would be a total loss.

It’s been over eight years since I first wrote about Augusta, Georgia's historic Miller Theater in a post entitled, “Movie Time.” Back then, the Arte Moderne facility, commissioned by Frank J. Miller and designed in 1938 by famed Chicago theater architect Roy Benjamin, had been empty for a couple decades and on the market for years. It appeared accessible, but before we could risk jail time or personal injury we encountered a realtor who saw us taking photos out front and asked if we’d like to have a look inside. Sometimes the easiest way really is the best way, so we took him up on the offer. The theater was huge and ornate, but inside it was cold and dark and hard to get decent photographs. Debris was scattered here and there. Water damage along the walls and ceilings was clearly visible and plaster was crumbling to the floor in places. The realtor said he figured the building could withstand perhaps five more years of vacancy before it would be a total loss.

Right now, restoration and renovation is getting underway, but most of the interior of the theater looks pretty much as it did when it shut down thirty years ago. This is especially apparent in the projection booth, where scraps of film litter the floor and the projector itself still sits, perhaps wondering if the day will come when it might return to life. I guess no one has told it that we're in the digital age. Oh well, Katherine Hepburn won’t be coming back for a return visit either. Elsewhere, old signs remain on the doors and ropes hang in the wings.

Right now, restoration and renovation is getting underway, but most of the interior of the theater looks pretty much as it did when it shut down thirty years ago. This is especially apparent in the projection booth, where scraps of film litter the floor and the projector itself still sits, perhaps wondering if the day will come when it might return to life. I guess no one has told it that we're in the digital age. Oh well, Katherine Hepburn won’t be coming back for a return visit either. Elsewhere, old signs remain on the doors and ropes hang in the wings.

an orchestra pit that can hold 45 musicians will be created. Eventually, a nine foot polished ebony Steinway grand piano will be brought in. Right now, something a bit more modest can be found. When fully outfitted, it’s said the acoustics will be superior to any other venue in the Central Savannah River Area. At 1325, the seat count will be a little less than the original theater, but still a few hundred more than the 800-seat Imperial Theater on the other side of Broad St.

an orchestra pit that can hold 45 musicians will be created. Eventually, a nine foot polished ebony Steinway grand piano will be brought in. Right now, something a bit more modest can be found. When fully outfitted, it’s said the acoustics will be superior to any other venue in the Central Savannah River Area. At 1325, the seat count will be a little less than the original theater, but still a few hundred more than the 800-seat Imperial Theater on the other side of Broad St.

Having also purchased the former Cullum’s building next door, there will be quite a performing arts complex at 7th and Broad St. when everything is finished. The Symphony Board’s stated mission is “to share the joy of great musical performance with our audience.” Those performances can only be enhanced by taking place in a building as soulful as the Miller Theater. “Together, we are music,” is the Board’s tagline. As I recall, Augusta could use some more music, too.

Having also purchased the former Cullum’s building next door, there will be quite a performing arts complex at 7th and Broad St. when everything is finished. The Symphony Board’s stated mission is “to share the joy of great musical performance with our audience.” Those performances can only be enhanced by taking place in a building as soulful as the Miller Theater. “Together, we are music,” is the Board’s tagline. As I recall, Augusta could use some more music, too.

The two top stories are faced with ornamental polychrome terra cotta in harmonious colors and the entire exterior of the building is trimmed in terra cotta---such as window sills, lintels, etc. All interior floors and partitions are fireproof and the elevator doors, windows on down-town side, etc., are also absolutely fireproof. The first floor lobby is decorated with a high marble wainscoting and plaster cornices. The offices and corridors on the upper floors have smooth finish plaster walls. The corridors all have tile floors and wainscotings of Georgia marble. Ample toilets are provided and they are finished in tile. The trim throughout is genuine oak with veneer doors. The heating system is the best that can be had with a vacuum vapor circulating system. There is enough radiation to overheat the building in zero weather if desired. All floors are provided with vacuum cleaning outlets so that the offices may be perfectly cleaned without dust. Sufficient electric lighting is provided throughout, and every office has a lavatory and an abundance of hot and cold water. There are also two fast elevators, perfectly equipped with indicators, insuring fast service."

The two top stories are faced with ornamental polychrome terra cotta in harmonious colors and the entire exterior of the building is trimmed in terra cotta---such as window sills, lintels, etc. All interior floors and partitions are fireproof and the elevator doors, windows on down-town side, etc., are also absolutely fireproof. The first floor lobby is decorated with a high marble wainscoting and plaster cornices. The offices and corridors on the upper floors have smooth finish plaster walls. The corridors all have tile floors and wainscotings of Georgia marble. Ample toilets are provided and they are finished in tile. The trim throughout is genuine oak with veneer doors. The heating system is the best that can be had with a vacuum vapor circulating system. There is enough radiation to overheat the building in zero weather if desired. All floors are provided with vacuum cleaning outlets so that the offices may be perfectly cleaned without dust. Sufficient electric lighting is provided throughout, and every office has a lavatory and an abundance of hot and cold water. There are also two fast elevators, perfectly equipped with indicators, insuring fast service."

countless times and never gave it a second thought. That was my mistake as the history of this place is fairly fascinating. However, the building is sort of designed to look unassuming. Three stories tall and made of brick, for some reason it was covered in stucco and then scored to look like it was constructed of cinderblock. It’s unassuming alright. And very old. Luckily, Rob Pavey of the Augusta Chronicle did an

countless times and never gave it a second thought. That was my mistake as the history of this place is fairly fascinating. However, the building is sort of designed to look unassuming. Three stories tall and made of brick, for some reason it was covered in stucco and then scored to look like it was constructed of cinderblock. It’s unassuming alright. And very old. Luckily, Rob Pavey of the Augusta Chronicle did an

clearly, in one of its last incarnations, a restaurant was on the lower level. There is no indication of its name, although the inscription “Good things to eat” remains on an outside wall. What I don’t have a picture of are the two camera obscurae which have been created by two little holes in the plywood covering the windows of the front doors. While mostly projecting the parking garage across the street, they are still eerily beautiful and, like the now-empty Lowrey Wagon Works building itself, known about by only a very few.

clearly, in one of its last incarnations, a restaurant was on the lower level. There is no indication of its name, although the inscription “Good things to eat” remains on an outside wall. What I don’t have a picture of are the two camera obscurae which have been created by two little holes in the plywood covering the windows of the front doors. While mostly projecting the parking garage across the street, they are still eerily beautiful and, like the now-empty Lowrey Wagon Works building itself, known about by only a very few.

I’m not sure if there’s irony to be found there or not. But I digress. The building was originally intended to be a commercial townhouse but by the late 1800’s it was a Chinese laundry operated by Sang Sing and Sang Lee. Clothes were washed into the 1900’s and then, in 1917, the building was bought by Mrs. Ellen J. Doremus, the daughter of former Augusta Mayor Charles Estes. Mrs. Doremus paid $8000 for the place and the lower level, at least, remained mostly commercial space. Now part of the first floor is home to a furniture refinishing shop but most of the rest of the building is vacant and just waiting for someone to come along and give it a helping hand. There's what appears to be about 120 years worth of

I’m not sure if there’s irony to be found there or not. But I digress. The building was originally intended to be a commercial townhouse but by the late 1800’s it was a Chinese laundry operated by Sang Sing and Sang Lee. Clothes were washed into the 1900’s and then, in 1917, the building was bought by Mrs. Ellen J. Doremus, the daughter of former Augusta Mayor Charles Estes. Mrs. Doremus paid $8000 for the place and the lower level, at least, remained mostly commercial space. Now part of the first floor is home to a furniture refinishing shop but most of the rest of the building is vacant and just waiting for someone to come along and give it a helping hand. There's what appears to be about 120 years worth of

the next few posts will document the places I photographed while back in Georgia. In addition to the safari buildings, I found a few new out-of-the-way spots and checked-out what remained of some old favorites, like that house above in the

the next few posts will document the places I photographed while back in Georgia. In addition to the safari buildings, I found a few new out-of-the-way spots and checked-out what remained of some old favorites, like that house above in the

About seven miles south of Ancho, down an unexpectedly bumpy gravel county road (I’ve gotta learn to pay better attention to map symbols), is what remains of Jicarilla. Named for the surrounding Jicarilla Mountains (jicarilla is Spanish for “little basket” or “little gourd”) and, by extension, the Jicarilla Apache, gold first started being pulled out of the area prior to the 1820’s. This is when the Spanish, followed by the Mexicans, came with pans and wooden bowls called “bateas” to work the creeks. Although, truth be told, it was often Native American slaves that did the actual work. In 1864, the U.S. Army forced the local Apache onto distant reservations. By then, Texans had been drifting in and trying their luck for over 20 years. Prospectors arrived en masse in the 1880’s and by 1892 Jicarilla had a post office, which also served as an assay office and store. That's it pictured above. At this time, about 200 people lived in Jicarilla and by 1900 a saloon had opened and the town had a Justice of the Peace.

It was during the Great Depression that the population of Jicarilla peaked at around 300, when desperate people tried to support themselves by gold mining. Actually, I think that kind of thing is happening around the country again right now. Mining could bring in as much as $7 per day and there was plenty of game to provide extra food. But Jicarilla must’ve been a little too remote for most folks as nearly everyone left once the economy improved. By 1942, Jicarilla was pretty much done.

However, some mining continued until relatively recently, when the Lincoln National Forest, which borders Jicarilla, decided to crack down on miners who lived or worked on federal land.

About seven miles south of Ancho, down an unexpectedly bumpy gravel county road (I’ve gotta learn to pay better attention to map symbols), is what remains of Jicarilla. Named for the surrounding Jicarilla Mountains (jicarilla is Spanish for “little basket” or “little gourd”) and, by extension, the Jicarilla Apache, gold first started being pulled out of the area prior to the 1820’s. This is when the Spanish, followed by the Mexicans, came with pans and wooden bowls called “bateas” to work the creeks. Although, truth be told, it was often Native American slaves that did the actual work. In 1864, the U.S. Army forced the local Apache onto distant reservations. By then, Texans had been drifting in and trying their luck for over 20 years. Prospectors arrived en masse in the 1880’s and by 1892 Jicarilla had a post office, which also served as an assay office and store. That's it pictured above. At this time, about 200 people lived in Jicarilla and by 1900 a saloon had opened and the town had a Justice of the Peace.

It was during the Great Depression that the population of Jicarilla peaked at around 300, when desperate people tried to support themselves by gold mining. Actually, I think that kind of thing is happening around the country again right now. Mining could bring in as much as $7 per day and there was plenty of game to provide extra food. But Jicarilla must’ve been a little too remote for most folks as nearly everyone left once the economy improved. By 1942, Jicarilla was pretty much done.

However, some mining continued until relatively recently, when the Lincoln National Forest, which borders Jicarilla, decided to crack down on miners who lived or worked on federal land.  I’ve been told that this was at least partially a result of miners dumping waste in the forest. Whatever the case, the last miner in the area was a man named Jerry Fennell, who had spent 30 years working his claim, finding a little gold here and there, and living in what had been Jicarilla’s general store until one day he was required to submit an official plan of operation. Unable to pay the reclamation bond, Mr. Fennell and Dusty, his well-named burro, shut everything down in the early 2000’s, the last in a line of miners stretching back to the Jicarilla and Mescalero Apaches, who extracted turquoise from the mountains in the late 1500’s.

I’ve been told that this was at least partially a result of miners dumping waste in the forest. Whatever the case, the last miner in the area was a man named Jerry Fennell, who had spent 30 years working his claim, finding a little gold here and there, and living in what had been Jicarilla’s general store until one day he was required to submit an official plan of operation. Unable to pay the reclamation bond, Mr. Fennell and Dusty, his well-named burro, shut everything down in the early 2000’s, the last in a line of miners stretching back to the Jicarilla and Mescalero Apaches, who extracted turquoise from the mountains in the late 1500’s.

Almost a mile to the south is the log schoolhouse above, built in 1907. Also functioning as a church and general meeting place, it was used through the Depression. The fellow from White Oaks that I mentioned in the

Almost a mile to the south is the log schoolhouse above, built in 1907. Also functioning as a church and general meeting place, it was used through the Depression. The fellow from White Oaks that I mentioned in the  During our visit there appeared to have been some recent activity around a more modern-looking green cabin on the east side of the road. This place is known as the "Hunt Casita," after a family that lived there in the late 1970's. But the post office, small adobe general store (not pictured), and schoolhouse are entirely quiet, as is most of the area around Jicarilla these days. Above is a photo from

During our visit there appeared to have been some recent activity around a more modern-looking green cabin on the east side of the road. This place is known as the "Hunt Casita," after a family that lived there in the late 1970's. But the post office, small adobe general store (not pictured), and schoolhouse are entirely quiet, as is most of the area around Jicarilla these days. Above is a photo from

Lincoln County, New Mexico is Billy the Kid country. The Kid gained his reputation in the Lincoln County War of 1878 and escaped the hangman’s noose by shooting his jailer’s in the Lincoln County Courthouse. I may do an entire post on Billy the Kid and the town of Lincoln someday, but right now we’re going to visit Ancho, in the northwestern part of Lincoln County.

Ancho (pronounced like the first part of “anchovie”) is Spanish for “wide” or “broad” and refers to the valley in which the town sits. Most towns in New Mexico were born by the railroad or minerals and Ancho owes its existence to both. The El Paso and Northeastern Railroad pushed into the valley around 1900 and designated that there be a stop in the vicinity. Within a year, a gypsum deposit was discovered not far away and a plaster mill was built, operated by the Gypsum Product Company. In 1902 (or 1905, depending on your source), a proper railroad depot was put up and some company houses constructed. In 1905, the Ancho Brick Company was created to utilize the abundant fire clay in the area.

Lincoln County, New Mexico is Billy the Kid country. The Kid gained his reputation in the Lincoln County War of 1878 and escaped the hangman’s noose by shooting his jailer’s in the Lincoln County Courthouse. I may do an entire post on Billy the Kid and the town of Lincoln someday, but right now we’re going to visit Ancho, in the northwestern part of Lincoln County.

Ancho (pronounced like the first part of “anchovie”) is Spanish for “wide” or “broad” and refers to the valley in which the town sits. Most towns in New Mexico were born by the railroad or minerals and Ancho owes its existence to both. The El Paso and Northeastern Railroad pushed into the valley around 1900 and designated that there be a stop in the vicinity. Within a year, a gypsum deposit was discovered not far away and a plaster mill was built, operated by the Gypsum Product Company. In 1902 (or 1905, depending on your source), a proper railroad depot was put up and some company houses constructed. In 1905, the Ancho Brick Company was created to utilize the abundant fire clay in the area.

For a time, the heart of Ancho was made of plaster and brick. Ancho-made bricks and plaster helped rebuild San Francisco after the 1906 'quake and more bricks were used for smelter stacks in Arizona. In 1930, the town used its own product to construct a large, brick schoolhouse, replacing the small, wooden, one-room job that burnt down. The school had as many as five teachers and 140 students. However, Ancho was in trouble.

For a time, the heart of Ancho was made of plaster and brick. Ancho-made bricks and plaster helped rebuild San Francisco after the 1906 'quake and more bricks were used for smelter stacks in Arizona. In 1930, the town used its own product to construct a large, brick schoolhouse, replacing the small, wooden, one-room job that burnt down. The school had as many as five teachers and 140 students. However, Ancho was in trouble.  In 1963, Mrs. Jackie Silvers purchased the old depot, somehow moved it off the railroad right-of-way, and then filled it with all manner of antiques from the area. My House of Old Things, as the “museum” was called, got a rave review in Varney’s

In 1963, Mrs. Jackie Silvers purchased the old depot, somehow moved it off the railroad right-of-way, and then filled it with all manner of antiques from the area. My House of Old Things, as the “museum” was called, got a rave review in Varney’s  Later, in nearby

Later, in nearby  “heartbreaking” given their relation to the history of ranching, farming, and homemaking in the region. Who knows what was sold, but peeping inside it appeared that much remains. Furniture, clothes, an old wooden letter box. Through one window was a mannequin head, seemingly presiding over the dust and decay, waiting for something to finally happen. It may be a long wait. The old playground, abandoned over 50 years ago, still stands, made of bolts and bits of pipe that no school would allow children to play on in this day and age. The school, pictured below, seems to have fared better and is now a church. Though who attends I have no idea.

“heartbreaking” given their relation to the history of ranching, farming, and homemaking in the region. Who knows what was sold, but peeping inside it appeared that much remains. Furniture, clothes, an old wooden letter box. Through one window was a mannequin head, seemingly presiding over the dust and decay, waiting for something to finally happen. It may be a long wait. The old playground, abandoned over 50 years ago, still stands, made of bolts and bits of pipe that no school would allow children to play on in this day and age. The school, pictured below, seems to have fared better and is now a church. Though who attends I have no idea.

Not one car passed down the road during our visit. The town was completely silent. Lightning flashed on the horizon and for a brief moment a few big drops of rain fell. Only one building seemed occupied and, indeed, we learned that someone does live there. So, this is Ancho in 2012, population 1.

As so often happens, most of the info for this post came from

Not one car passed down the road during our visit. The town was completely silent. Lightning flashed on the horizon and for a brief moment a few big drops of rain fell. Only one building seemed occupied and, indeed, we learned that someone does live there. So, this is Ancho in 2012, population 1.

As so often happens, most of the info for this post came from  A few weeks ago we visited an unusual

A few weeks ago we visited an unusual  In fact, the place still attracts cattle and on the day we visited they were milling all around, lowing and looking alternately angry and confused by our presence. The noise actually made it hard to concentrate on exploring. Thankfully, they eventually got bored and wandered off into the desert somewhere. Exactly when the ranch might have been abandoned I have no idea, but I'd say it's been empty for a few decades now. There are still some canned goods in the kitchen, but I wouldn't eat them if I were you.

Adjacent to the ranch is a holding pen and a water tank, so the cattle weren't there for nothing. Apparently some ranchers must still be using the site to hold livestock, but it didn't look like the house had been entered in quite some time.

In fact, the place still attracts cattle and on the day we visited they were milling all around, lowing and looking alternately angry and confused by our presence. The noise actually made it hard to concentrate on exploring. Thankfully, they eventually got bored and wandered off into the desert somewhere. Exactly when the ranch might have been abandoned I have no idea, but I'd say it's been empty for a few decades now. There are still some canned goods in the kitchen, but I wouldn't eat them if I were you.

Adjacent to the ranch is a holding pen and a water tank, so the cattle weren't there for nothing. Apparently some ranchers must still be using the site to hold livestock, but it didn't look like the house had been entered in quite some time.