skip to main |

skip to sidebar

I might as well stop pretending that I’m going to post more regularly and admit that, modern life being what it is, time is always tight, and seemingly ever-increasingly so. However, one way to get new posts written is to take to my sick bed and thus find myself confined to the small space between the bedroom and kitchen table. As such is the case today, let us leave the hustle and bustle of modernity behind once again and step back into the past, this time to visit Lingo, New Mexico.

The little village of Lingo, which can still claim at least one family as residents, is on the eastern edge of New Mexico, just five miles from Texas. It’s a tiny dot on the map at the western extremity of the staggeringly vast Llano Estacado/Staked Plain plateau. As such, it sits among some other places we’ve visited in the region, such as Pep, Causey, House, and Highway.

Jean M. Burrough’s “Roosevelt County History and Heritage” leads off with a handwritten letter about the Bilberry family’s arrival in what was not yet Lingo. They lived in a “two-room shack, dirt floor” and Finis Bilberry farmed and raised sheep. School was first held in 1916, the schoolhouse being a one-room dug-out at a place regrettably named Nigger Hill. Also known as Dead Negro Hill, this was where, in July 1877, a group of African-American soldiers and buffalo hunters abandoned their pursuit of some Comanche who had stolen stock and killed one hunter. Desperate and dying of thirst in the summer heat, the men began to search for water, some going 86 hours without a drink. Five would die in this incident, which was sometimes remembered as the “Staked Plains Horror." Finally, in 2005, the name of the rise was officially changed to Buffalo Soldier Hill.

Speaking of place names, in “The Place Names of New Mexico,” Robert Julyan notes that Lingo was known as Need in 1916, becoming Lingo in 1918. No one knows why it was originally called Need, but in 1918 the postal authorities thought the name too close to Weed, a settlement down south in Otero County. At that point, not only did Need become Lingo, but the post office got moved three miles to the north. I don’t know why the post office also had to move. Anyway, it’s been speculated that Lingo took its name from the way the people spoke (i.e., “the jargon, slang, or argot, of a particular field, group, or individual”), but more probably it references a family, now forgotten.

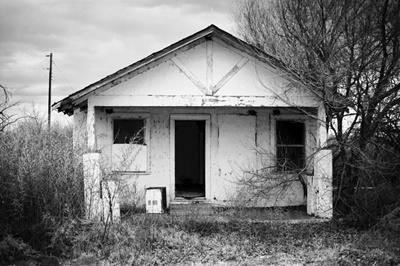

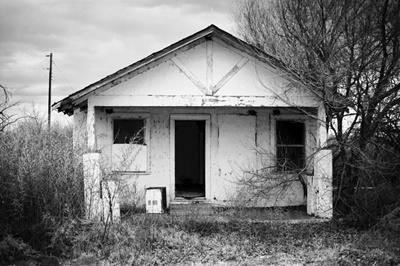

Now, I often feel like City of Dust is in a race against dusty oblivion as so many of the buildings documented on this blog are disappearing fast, and those in Lingo are no different. But unlike Lucy, NM, where I got there too late to photograph the old school or the Formwalt house, in this case I arrived just in the nick of time. Shown above and at left is the post office, where around 1953 a Mrs. Balko was postmistress. Mrs. Fanny Brown took the position on April 20, 1968, staying until the post office closed in 1984 (possibly on November 2). I visited on December 12, 2015 and on Valentine's Day 2016 the old PO burned to the ground. Apparently someone was driving a pick-up with a BBQ grill in the back and hot coals became airborne. Numerous blazes were started, consuming a total of 1,083 acres in southeastern Roosevelt County, but at least no one was hurt and no other structures were damaged.

Shown above and at left is the post office, where around 1953 a Mrs. Balko was postmistress. Mrs. Fanny Brown took the position on April 20, 1968, staying until the post office closed in 1984 (possibly on November 2). I visited on December 12, 2015 and on Valentine's Day 2016 the old PO burned to the ground. Apparently someone was driving a pick-up with a BBQ grill in the back and hot coals became airborne. Numerous blazes were started, consuming a total of 1,083 acres in southeastern Roosevelt County, but at least no one was hurt and no other structures were damaged.

Below is the crumbling Lingo Baptist Church, reportedly also used by other denominations on occasion, possibly after a second church in town closed. The general store is shown at the top of this post. Other buildings included a café, hardware store, basketball gym, and a shop in a Quonset hut, none of which still stand.

Fish fries and dances were held at the high school, which was across the street from the post office. The dances were a big deal as such stuff was not allowed in nearby Causey. However, Causey was where you would go to get your hair styled by the much-loved Lingo resident Edna Ashbrook. Lingo’s last graduating class was in 1945 and numbered five: Meryl Terry, Pete Rogers, Billy Joe Cunningham, Otis Foster, and Gene Collins. You can still find the blacksmith shop, but it’s fallen into a jumbled heap. Things are certainly much quieter than when Lingo could boast of the Hair twins--Judson and Jettie--and the Henry triplets--Anna, Bunna, and Lanna--although, you know, sometimes quiet can be nice.

Now I must return to my Theraflu.

The only published sources of information on Lingo that I could find were Burrough’s “Roosevelt County History and Heritage” and Julyan’s “The Place Names of New Mexico.” Wikipedia has a long entry on the “Buffalo Soldier tragedy of 1877.” Everything else for this post came from the many good people that left their recollections of growing up and living in Lingo on a series of photographs on the City of Dust Facebook page. Those photos and the accompanying comments can be found HERE, HERE, HERE, and HERE.

In Socorro County, New Mexico, tucked off a side road that parallels I-25, not far from a muddy stretch of the Rio Grande, is the little village of Contreras. This was where a man named Matías Contreras once raised cattle and sheep and gave his name to a small community. A post office opened in 1919 but closed in 1935.

Not far south of Contreras is La Joya, the literal end of the road, and, in fact, a map from 1918 has Contreras as Los Ranchos de la Joya. La Joya’s recorded history post-European contact goes back much farther, to 1598, when Juan de Oñate's expedition found a Piro Indian pueblo there and called it Nueva Sevilleta because the setting reminded the Spanish explorers of Seville, Spain.

To me, the most striking building in Contreras is the old, long-empty school, naturally. I don’t know much about it, but I do know that students were attending classes there in the 1930’s. So perhaps it's one of the many Works Progress Administration (WPA) structures built in the area around the time of the Great Depression. Nearby Alamillo has a WPA school that became (and might still be) a residence, although it looks quite different.

There used to be a plaque to the right of the front doors (see top photo), which I somehow managed to miss. Later I was told it commemorated some local folks involved with the school, but before I could get back to look more closely it had been removed. I don’t think it was stolen though; probably it was taken off because the building is in such poor condition. Maybe whoever has it will read this and tell us what it says! I should mention that I photographed the school a few years ago and not only is it in worse shape now, it's also been fenced-off.

Otherwise, the San Jose Catholic Church, part of Our Lady of Sorrows Parish, is well-maintained and hosts a fiesta in March. There are no going commercial or civic concerns, but there are some well-kept homes and, if you visit whilst under the vengeful eye of the relentless afternoon sun on a parched, triple-digit day, plenty of dust. Of course, as this is the blog for connoisseurs of dust, everything is as it should be with this trip to Contreras, New Mexico.

There’s not a lot out there on Contreras, so pretty much all the historical information for this post came from Robert Julyan’s trusty “The Place Names of New Mexico.”

I have a backlog of so many small towns and villages in New Mexico that I may well never get to them all at this rate. But I can keep trying! Next time I’ll just reach my hand into the hat and see what I pull out.

MARCH 2023 UPDATE: I am beyond thrilled to be able to make available here one of only two known firsthand descriptions of life in Ricardo, New Mexico. This account, spanning from 1908-1916, is contained within Zorene Thompson's wonderful memoir, "OUR LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE." In addition, there's an ADDENDUM TO CHAPTER 5, which goes deeper into the story of Della Carley, who shot two people at the Ricardo post office in 1912. To download the PDF's, just right-click on the file names above and do the ol' "Save Link As..." trick. A big City of Dust thank you is due to Zorene Thompson's son, Ray Mack Thompson, for assembling his mother's rare story and making it available to all, a true labor of love! Thanks also to Jacalyn Carley, the granddaughter of Della Carley, for generously providing a chapter from her own family's history in Ricardo!

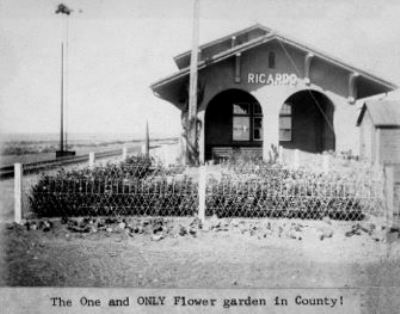

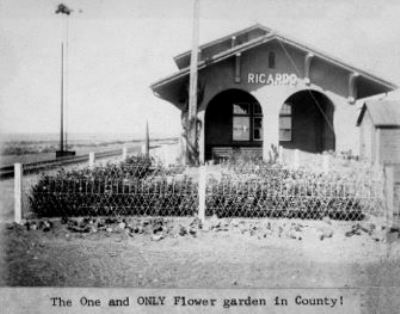

Ricardo, New Mexico, is yet another of the many towns that came to life seemingly overnight as the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad (AT&SF RR) built the Belen Cut-off through the east-central part of the state. Located in De Baca County, a few miles south of Highway 60, the recorded history of Ricardo appears to be scant at best. The village’s name is thought to have been that of a railroad official, and Ricardo, right along the tracks, was an AT&SF RR section house and water station.

Sadly, on the night of May 6, 1908, a massive fire started in the large Grosh and Strayhorn store, spreading to the Ricardo Hotel, the barbershop, and most of the town. The Santa Fe New Mexican said that Ricardo was "reduced to ashes." However, rebuilding commenced, and the post office opened the same year, doing business until 1956, after which point the mail went to Fort Sumner. There was also a schoolhouse, which I’ve been told was comparable in size to the First Presbyterian Church of Taiban. In the late-1950s, the school was purchased and hauled away so the lumber could be reused. A vintage photo of the train depot would seem to indicate that Ricardo at one point had "the one and ONLY flower garden" in De Baca County.

While virtually none of Ricardo is as it was (the post office became part of a ranch home; a general store collapsed), one gem does persist—at least for now—and that is a wonderful and spacious two-story rock and plaster structure, which may have been contructed in 1908 as a tuberculosis sanatorium that never held any patients. In the late 1920s, it's said that locomotive firemen who provided assistance shoveling coal to get freight trains up the long hill to Vaughn were briefly stationed here. It was headquarters to the adjacent ranch, as well. A later renovation for a family home was found to be impossible and now it is quite near collapse. However, having become the lone sentinel over this small part of the eastern plains, much of its old charm and majesty somehow remains. It’s not hard to imagine a family tending the stone walkway, or perhaps lounging on the porch of a fine spring morning, the wildflowers blooming way-off into the distance. If you’re quiet, beneath the prairie wind you can almost hear boots slowly climbing the shattered wooden stairs.

In the late 1920s, it's said that locomotive firemen who provided assistance shoveling coal to get freight trains up the long hill to Vaughn were briefly stationed here. It was headquarters to the adjacent ranch, as well. A later renovation for a family home was found to be impossible and now it is quite near collapse. However, having become the lone sentinel over this small part of the eastern plains, much of its old charm and majesty somehow remains. It’s not hard to imagine a family tending the stone walkway, or perhaps lounging on the porch of a fine spring morning, the wildflowers blooming way-off into the distance. If you’re quiet, beneath the prairie wind you can almost hear boots slowly climbing the shattered wooden stairs.

You don’t have to be quiet to hear cows though, a couple dozen of which may be quite excited to see you until they learn you have no food. Then they just seem vaguely hostile. I assume the concrete structure below was once used to water such cattle, but I’m not certain. Perhaps someone can provide some insight.

I should also mention that not only is Ricardo remote, it's on private ranchland. At one time I thought it might've been owned by the railroad, but that's not the case. So unless you have an invitation and a way with cows, it is best not to just show up on the porch of the last house in Ricardo.

And that's all I know about the ghost town of Ricardo. I would love to hear more from anyone that might have something to tell, so please leave a comment if you do. For now, “The Place Names of New Mexico” has the most to say, and I picked up a bit more info from some knowledgeable viewers of the City of Dust Facebook page. The short news piece, "Fire Wipes Out Ricardo," was published by the Sante Fe New Mexican on May 8, 1908. I got the vintage photo from NM ghost town photographer Beata Certo, but no one knows the original source. Anyway, thanks, folks!

Next time I believe we’ll visit Contreras, down in Socorro County.

Despite the photo from Cedarvale, New Mexico above, this isn't a ghost town piece. Instead it's yet another story to fill in the time between my all-too-infrequent posts. This one is called...

THE WAR CORRESPONDENT

“You’re married? You’re fucking married?!”

I’m nearly—finally—asleep when suddenly a girl yelling in the room above mine jolts me back awake. My first reaction is one of pure anger. I haven’t slept in a very long time, and for the last 12 hours I’ve been nearly frantic to close my eyes. I’d driven over 36 hours straight with only a couple of quick naps at rest stops along the way. Out of nowhere Monday morning we needed to get a load immediately from our warehouse in Provo, Utah down to near Miami and my regular rig, which I could at least sleep in comfortably, was getting transmission work. All that was left to drive was a beat-up box truck, and between that and the tight deadline, decent sleep had not been in the cards. But I’d dropped off the load, gotten a quick bite, and checked into some place called the American Economy Inn not far from the beach to get my head down before starting the long haul back in the morning. So, I’m pissed to be awake. However, in another instant, curiosity takes hold.

“Oh my God!” yells the girl. Then an octave higher: “Oh! My! God!”

The man’s voice is deep and hard to understand through the floor. It sounds even and steady though. He’s trying to calm her down. There’s some stomping and another “Oh my God!” My stomach tightens and I’m ashamed of myself. Why should I feel anything for these people? I just want to be asleep. I hear the man again and make out a few words. “Baby.” “Her.” “You.” “Sorry.” I could fill in the rest myself if I wanted to.

Then there’s a crash and I wait for the inevitable. Real screaming. Harder stomping. All followed by a door slamming and then, maybe, a chance to get some shut-eye. I hope it won’t drag on too long, but then minutes pass with no sound at all. I listen harder, which only increases my wakefulness. Still nothing. Then there’s the unmistakable slow, rhythmic squeak of the bedsprings of a cheap motel mattress. Listening to other people have sex can be infuriating or depressing and in this case it’s both. So I turn on the light and put on my jeans and boots. The clock says 1:43AM. “Unbelievable,” I mutter, though there’s nothing remotely unbelievable about it. I wish I could call the guy’s wife. Not that I’m overly concerned about morality here, mind you, I just want some sleep.

There’s nowhere else to go so I get in the truck and turn on the radio. Two men are discussing ISIS in serious, somber tones. Where they come from, what they believe, how much money they have. In my exhaustion I’m struck by the thought that the modern world of dingy motels and run-of-the-mill adultery is going to have its hands full for quite some time battling the ancient world of religious martyrdom and apocalypse.

I listen to the radio for a while and must somehow eventually fall asleep because when I open my eyes I can see a thin paling of the darkness along the horizon just above the ocean. The clock on the radio says 4:52AM and a different man is talking about the weekend’s upcoming football games. My back and neck are stiff and I struggle to move as the blood painfully returns to my numb left arm, which has been pressed against the door. I turn the key, worried that the radio will have killed the battery, but the truck fires right up. So I cut the ignition, switch off the radio, and haul myself out of the cab. I’m too disoriented now to properly focus my anger on the couple upstairs as I stumble through the pre-dawn humidity back to my room where I sit on the bed, pull off my boots and jeans, and at last tumble into sweet oblivion.

Only the oblivion doesn’t stay sweet for long. Soon I’m dreaming that I’m wandering on a darkened battlefield amongst smoldering craters and mangled military equipment. Yet I can see no one either alive or dead. In my left hand is a camera and in my right a microphone but there’s nobody to speak to or document. I am too late for the war. The sense of failure is shattering, like I’ve let the entire world down. All those who might’ve fought here will go unnoticed and unremembered. As I walk slowly through the wreckage a hard, cold rain starts to fall, and the muddy ground begins to run with what looks like blood. But just as I’m about to scream I’m awoken yet again, this time by a knock on the door.

“Housekeeping!” I raise myself off the pillow and for a moment can’t recall where I am. Another knock: “Housekeeping!” The clock on the stand says 9:41AM.

“Not yet,” I answer, hardly recognizing my own wracked voice. “Half an hour, please.”

“Okay, sir,” is the reply through the door. “Sorry to disturb you, sir.”

I listen to the cart move further down the hall and then get out of bed and into the shower. In less than 30 minutes I’m walking across a sand-strewn parking lot toward the Flamingo Restaurant, a run-down 60’s-era joint next to the motel, with a voucher for a $5 breakfast. I sit on a faded pink stool at the blue and gold spangled counter, drink some coffee, and eat two runny eggs while I try to pull myself together. I think about how I didn’t plan on being a truck driver. I know plans don’t really mean much in life, but I never even made it to college. Then Cody came along before I’d turned 23 and that was that. I don’t mean to make it sound like Cody was the end of anything though. Really, he was the beginning. At 17, a junior in high school, he’s already a better man that I’ll ever be and I can’t claim any credit for that. He’s his own person, thankfully. For the last 10 years he’s lived with his mother and I’ve helped out as best I could. At first I’d visit only when I felt able to face him and his mom. It was harder when he was small, but it feels like it’s getting easier now. I’m grateful for that.

After breakfast I get in the truck and am about to hit the road when my phone rings. It’s my boss, Lindy.

“Dan, that was nice driving the last couple days. Damn heroic.”

“Thanks,” I reply. “I guess it was one for the books.”

“Sure enough. You made everyone happy.”

I almost laugh at that, but don’t.

“Listen,” continues Lindy, “take your time getting back. Find a couple places to stay. Some nice places. But, you know, maybe not too nice.” I do laugh at that. It doesn’t seem like there could possibly be a nice place between where I’m sitting and home. “And take the weekend off. In fact, I don’t want to see you ‘til Tuesday.”

I’ve worked for Lindy for eight years, often putting in six day weeks—sometimes even seven—and he’s always been good to me in return. It means something these days. It’s why I’ve stuck around.

“Thanks,” I tell him. “I appreciate that.” And I do.

“I know,” he says. “And I appreciate you handling this run. Now get back here safe.”

I tell Lindy I will and hang up. With the weekend free I figure I should give Cody a call and see what he’s up to. I make a mental note to do that later, telling myself not to let it slip like I have so many times before.

There’s a lot of road ahead of me. I’m still tired and I’d like to put in at least 10 hours before taking Lindy up on his offer. The sun sits low out over the water, gathering power. Happily, traffic is very light and moving fast. I get up to 80, about as fast as the old box truck will go, and start making good time. I’m fiddling with the radio, trying to avoid the news, when a car up ahead changes to the right lane without looking, pushing the car next to it off the highway. Then the first driver overcorrects in an attempt to get back into the left lane, slides sideways, and flips completely over, landing upside down at the bottom of an overgrown embankment. The other car has also flipped, but landed right side up on a flat spot near a swampy depression off the road farther back, its roof crushed.

I pull onto the shoulder and jump out of the cab. I smell the acrid tang of burned rubber. A puff of black smoke hangs in the air. A woman is screaming from the car that’s upright, but everything seems strangely quiet and still. I call 911 and tell them there’s been a serious accident. I give my best guess at the mile marker number and even though the operator tells me to stay on the line I hang up. The woman continues screaming, but I’m closer to the other car, so I run to that one, already breaking a sweat. At first I can see no movement inside. In the driver’s seat a man is strapped into his safety belt, hanging upside down against the roof. I kneel in the tall grass and yank on the door. It opens and I reach for him. He’s dazed and bleeding badly but alive. Then he opens his eyes wide and yells, “My son! My son!” He waves his hand toward the passenger seat but the child is actually lying on the roof, near the rear window, completely still. So much blood covers the man’s face that he can’t see his boy.

“He’s here, sir,” I say, surprised at how calm I sound. “I’m going to help him first.”

I run around the back of the car and smell gas. I know cars don’t usually blow up like you see on TV, but if there are fumes then the fuel system might no longer be sealed, and it occurs to me that maybe the vehicle is combustible. I kneel to get at the rear door handle and pull. The door is jammed, but I feel it give slightly so I try harder. It finally opens and I gently pick up the boy. He is perhaps six or seven and there is no blood on him at all. I think he must be dead but then his chest rises weakly. With the man’s son in my arms I run from the car to the grassy slope of the embankment by the highway and gently set him down in a patch of sparse vegetation. Some people have gathered and a middle-aged woman crouches beside me. She says she’s a nurse and begins to look at the boy. Without saying a word I get up to return to the man and it’s only then that I realize the woman in the other car is still screaming. Another man is trying to get her out of her vehicle, but I run back to the upside-down car and a third man follows me. This man and I work together to extricate the driver, whose scalp I now see has been partly torn from his skull, likely after hitting the spider-webbed windshield. He lapses in and out of consciousness as we undo the seatbelt carefully so he does not tumble onto the roof. The smell of gas is much stronger.

Quickly covered in the driver’s blood we slide him from the car. His left arm hangs limply from his side and it looks like his collarbone has been broken. We slowly carry him to the grassy slope and, as we do, I see the other man carrying the woman in his arms. She has not stopped screaming, but somehow it has become mechanical, the sound almost disembodied. The ground is wet in that direction and the man lifts his legs high to free them from the mud with each step as he moves towards us. We all converge on the slope and the woman is also covered in blood, a white stump of bone sticking through her thigh below her torn dress.

Finally I hear sirens growing closer and the state patrol arrives. Next come ambulances and a firetruck. We all step aside and let the paramedics get to work. Some firemen inspect the vehicles and then the firetruck begins to douse the car that’s upside-down. The injured woman suddenly goes quiet and is loaded into an ambulance. The man and his son are put in other ambulances. Bystanders begin to wander back to their cars. With traffic reduced to one lane, a line of vehicles snakes into the distance. Having seen the entire accident, I’m asked by the state patrol to provide a report. The officer goes through some questions and since there isn’t all that much to tell it’s over quickly. I’m given some forms to fill out with my contact information and it’s hard to keep the pen steady. Investigators arrive with measuring tools and tow trucks ease their way off the highway toward the crumpled vehicles. No one says, “Good work,” or “Nice job.” I’m not certain that I’ve done the right thing. Should I have done more? Should I have done less? I simply don’t know.

Then I walk to my truck and find the man who helped the woman doubled over behind it, vomiting. I try to light a cigarette but begin shaking and have difficulty getting the lighter to flame. The man straightens, wiping his chin with a sleeve, and I ask him if he wants a smoke. “I quit years ago,” he says, but an instant later reaches for the outstretched pack. Somehow I manage to light us both up and we stand there silently watching the wreckers and policemen. I’m quickly down to the filter and then all I can think to say is, “Be safe.” The man nods and replies, “You, too.” I climb into the truck and ease slowly into traffic that stretches far back along the highway, where tragedy comes fast and often.

It doesn’t take too many miles before I know that I need to get off the road. I’m halfway across the parking lot of a Super 8 when I remember there’s a lot of blood on my clothes. The woman at the front desk eyes me warily until I explain that I was just at the scene of an accident.

“Oh my god!” she exclaims. “A couple ambulances went past half an hour ago. That’s an awful stretch out there. Wrecks all the time. Bad ones.”

I ask if she’s heard anything about the people that were injured, but she hasn’t. She gives me a room for half price and even though it’s on Lindy anyway I don’t dismiss the gesture.

I take a long, hot shower and get dressed. I walk outside to the dumpster and toss my bloody clothes inside. Then I call Cody. The sun is setting and the steady woosh of cars off Interstate 75 mixes with the voices of travelers around me.

“Hey, Dad,” answers Cody after a few rings.

“Hi, buddy. How are you?”

“Pretty good. What’s up?”

“Well, you know, I just got the, uh, weekend off.” My voice is unsteady, all adrenaline now completely drained from my system. “You wanna go to the football game Sunday?”

“Sure,” he says. “Sounds good.”

“Alright, I’ll, um, try to get us some tickets and, uh, call you Saturday.”

A few seconds pass.

“Dad?”

“Yeah?”

“Are you okay? You sound kinda funny.”

All at once I’m afraid I might start crying. Hard. Like maybe I won’t be able to stop. I take a breath. “It’s been a tough day.”

“A bad one?”

“Yeah.” I press my fingers to my eyes. “Pretty bad.”

“You want to talk about it?”

“I do.” And that’s the truth. Still, I can’t. Not just then. “But I’ll tell you about it when I see you. Give you the full report.”

“Okay. Where are you, anyway?”

“Florida.”

Cody laughs. “Florida?! No wonder you’ve had a bad day. Florida sucks.”

I smile. “Yeah.” Then I hesitate, like I always do, a weakness inherited from my own father. But I make sure I get the words out: “Love ya, buddy.”

“Love you, too, Dad.”

I walk back to my room and lie down on the bed. I listen to the clock radio—the oldies station—as a patch of sunlight travels across the carpet. Then the room is filled with shadows, and finally it goes dark as Carole King sings me to sleep. Never once do I hear so much as a peep from upstairs.

The next morning I wake up starving. I have plenty of carbohydrates and a cup of scalded coffee at the continental breakfast and then I’m back on the road. It’s still early and I turn the radio on. Overnight there have been mass killings in three more countries. Suicide attacks. Car bombs. Retaliations upon retaliations. I think about the tragedies within those tragedies, the battles waged in individual lives, no less important because they go unrecorded. Could anybody’s god stand to bear witness to them all? I turn off the radio and get ready for a long piece of I-75. I give the rattling box truck a little more gas. I’m heading for home, the fighting over for now.

If you like this kind of thing, there's more HERE. And HERE. And HERE, too.

The photos were all taken over the last couple years with a WOCA 120G that does what it wants no matter how much Gorilla Tape I put on it.

The Homestead Act of 1862 was an attempt by the U.S. government to entice citizens to open up the West by offering 160 surveyed acres in exchange for a five-year commitment to reside on the property. Untold numbers of people who couldn’t afford their own farms and ranches or struggled at difficult factory jobs in crowded cities thought that sounded pretty good, and they quickly hitched up their wagons or hopped on a train.

This sometimes isolated and remote land was often accepted sight-unseen by would-be homesteaders and, while many did find fields fertile for farming, others did not. Some then tried to eke out a living as best they could; others got right back on the next train heading in the direction from which they’d just come. While the history of Dunlap, New Mexico doesn’t go back quite as far as 1862, it's in the homesteading spirit that those who settled here came to find themselves in this sparsely populated part of the eastern plains.

It was W.O. Dunlap who founded the town in De Baca County, about 35 miles southwest of Fort Sumner, and gave it its name. He scouted parcels for incoming homesteaders and a community developed. In 1907, a post office opened. However, as the years passed, many in Dunlap began to find it harder and harder to survive off this land, and most eventually left. Most that is, but not all. In fact, Dunlap persists as a small, close-knit rural community to this day.

The post office closed in 1961, possibly taking the general store with it. Now no evidence of either remains. And, really, it’s the lone building they once stood next to, the Dunlap Community Church and School, which was for many years the heart of this area. Worship, academic instruction, community discussions, and just plain-old get-togethers all happened in this little place on the prairie.

There's little documentation of Dunlap that I can find, and perhaps the best look back has come from a couple people who grew up there and shared their memories on the City of Dust Facebook page. I hope they won’t mind my including their words here and might even approve of this brief history of a place of which they clearly remain quite fond.

"Our ranch was the closest to the school. Once one of the teachers lived in our bunkhouse. Miss McCoy, I believe. My mother played the piano for all the plays and programs! No one's mentioned the dances! Hot times Dunlap!

“My family and our friends share a long memory of a uniquely close life in an isolated area but the memories of those times do not fade at all in my heart.” SS

“My family homesteaded and ranched in this area, and my grandmother, her brother, and my dad all attended school here. Dunlap was the hub of the ranching community. Dances and other social events were held in that building. It was a school, church, and community gathering place. There was also a post office and general store there.

"My grandmother used to ride her horse--or drive a horse and buggy--to the school. My dad, his cousins, and several friends all attended school there until they completed 8th grade, when they transferred to different high schools. My dad's last year there was around 1955. I last attended a church service there in the early 1980's, right before I left for college.” JDW

Some wonderful photos from 20 years ago, when the Dunlap Community Church and School was in much better condition (and still had the piano!), can be found at AT&SF in Roswell. I highly recommend taking a look. And I’m not just saying that because City of Dust gets a mention!

Thanks very much to JDW and SS for providing the kind of remembrances you can’t find through Google. If anybody else would like to leave recollections, please do so. Additional info for this post came from Robert Julyan’s trusty “The Place Names of New Mexico.” You can find a synopsis of a 1996 interview with W.O. Dunlap's grandson, Ralph, HERE. Finally, I should mention that the land on which the Dunlap Church and School sits is privately owned. Feel free to contact me if you would like further information.

Those of you who are fans of the Roadrunner and Wile E. Coyote might be excited to hear that there was once a town in New Mexico named Acme. However, the corporation which lent its name to the place made cement blocks not jet-propelled unicycles. In the early 1900’s, the Acme Gypsum Cement Company built a mill slightly south of the Clovis Highway (supplanted by present-day U.S. 70), 17 miles northeast of Roswell, where aliens would later badly botch a saucer landing.

In 1907, the Acme School commenced lessons from inside a tent. Later, a one-room frame and plaster school was built on the western edge of town, placed so as to keep the students away from the dust and smoke of the mill. Grades 1-8 were taught and kids had to bring their own books and supplies, along with their lunches.

Acme boasted a hotel, large horse barn, general store, depot, and some company houses for workers. Its post office opened in 1906 and closed in 1946, by which time the Acme Gypsum Cement Co. had been out of business for ten years. When the mill closed, it was estimated that there were 30-40 people in Acme, of which 20 were children. Now there is nothing left of Acme at all, except for the cemetery, which is north of U.S. 70, half a mile away from where the mill once crunched gypsum.

One hundred meters from what doesn’t remain of Acme is the photogenic ruin of the Frazier School. So close together that some people seem not to distinguish between Acme and Frazier, their existence overlapped slightly. Frazier was established later and survived longer...but not too much longer. Frazier’s post office opened in 1937, a year after the Acme mill closed. That same year the Frazier School was built. Funeral services were also held in the school since the Acme Cemetery was nearby. I assume that anyone who died in Frazier was also buried in the Acme Cemetery. I also assume funerals weren’t held during class, unless mortuary science was on the curriculum.

Now, Frazier was a community of folks trying to make it through the ongoing effects of the Great Depression as best they could. Many of those who worked at the Acme Gypsum Cement Co. had moved on and almost the only employment in the area was to be found in the dusty, meagre soil of the eastern plains. Some ranchers did have cattle, and one enterprising rancher is said to have herded turkeys as if they were sheep. Coyote skins could be sold at Bond-Baker Wool and Hide Co. for $1.50-$5.00 per pelt, and the meat of a cottontail rabbit might be worth $1.00. Still, many families lived in dugouts or other similarly challenging shelter.

Yet these homesteaders wanted their children to receive a good education. So, it was C.M. Martin, the Chaves County superintendent, who designated that a new school, larger than the one in Acme, be built on land donated by Otis L. Shields. Then Lake J. Frazier secured a contract with the Works Progress Administration for construction, and thus both the school and the community were named for him. This would be the last one-teacher school built in Chaves County.

Stones were gathered from the area for building material, and black volcanic rocks framed the windows and doors. White rocks were used to create a five-point star above the front doors, and a steer’s head with longhorns was set in the eastern wall. There was one double-size room with a smaller room on each side partitioned by double doors. There was no electricity, but six large north-facing windows let in lots of sunlight (see photo above). Nor was there running water, but a stone tower out back contained a cistern on top, as well as coal storage below. “WATER” was spelled-out in volcanic rock along the tower’s top (see photo below). Mesquite roots augmented the coal supply when it came to providing heat. Teachers were required to check the route for rattlesnakes before allowing a child to use the outhouse.

As soon as it was completed, pupils attending the Acme School moved to the Frazier School, as did their teacher, Margaret Harrison. There were 24 kids that first year and Mrs. Harrison boarded with the family of Mac Smith, who ran a store and gas station, as well as the post office. Some students walked to school, but those on ranches were picked up in a car. Horse-drawn implements were used to finally make roads suitable for busses. Mrs. Harrison had already moved to another school by 1938 and teachers came and went frequently in Frazier.

Frazier was an active community through World War II, but, after the war, enrollment in the school dropped below the mandatory eight pupils and it closed in 1945. Students in the area were then sent to Roswell. For a time the school was used a community center, but eventually even the need for that withered. Now, not a soul remains in Frazier and the ruins of the stone school, once the pride of many, are all that marks this place.

Most information for this post came from The last one-teacher school is special to many, in the December 27, 1996 edition of the Roswell Daily Record, as well as Acme’s heyday was from 1905 until late 1930’s, in the November 29, 1996 edition of the same. Both articles were written by Ernestine Chesser Williams and can be found in her collection, “Chaves County Schools 1881-1968: Treasures of New Mexico History.” The only place that has copies for sale is the Historical Society for Southeast New Mexico in Roswell. As usual, Robert Julyan’s “The Place Names of New Mexico” provided some detail, but Williams reported details available nowhere else.

Incidentally, Williams’ little homemade book seems to have debunked at least the location of the reputed Billy the Kid “croquet” photograph as her drawing of the original Flying H School looks nothing like the building in that photo. Pretty cool.

After last month’s epic 1,600 word post on the bayside ghost town of Drawbridge, California, let’s make some concessions to time and ADHD with a snack-sized post on the tiny dot on the map of eastern New Mexico known as Highway. Located on NM Highway 206 between Pep and Milnesand, perhaps 12 miles from the Texas line, Highway got its name because...well, it's located on a state highway. Locals will tell you it should be "Hiway," but NMDOT has other ideas. There isn't a post office and I don't think there ever was one, although there are a few inhabitants.

The building pictured above is probably the most prominent in Highway (or Hiway!), and was a welding and mechanic shop for many years. At first, the construction had me thinking it might’ve been a church or school. Oscar "Pouch" Lott lived and worked here most of his life and still maintains the reputation of having been the best blacksmith in the area. The precise function of the structure pictured below remains obscure, but if I had to guess I’d say it was something to do with water.

Hiway (or Highway!) is in Roosevelt County, and perched just inside the western half of that mighty chunk of high, flat tableland known as the Llano Estacado. You can read a bit more about this legendary feature in previous posts on the nearby towns of Pep, Causey, and House.

Everything I could learn about Highway came courtesy of Robert Julyan’s “The Place Names of New Mexico” and helpful viewers commenting on THIS post and THIS post on the City of Dust FACEBOOK PAGE.

Soon we’ll visit the twin ghost towns of Acme and Frazier, New Mexico, perhaps 50 miles southwest of here as the crow flies, and not too far from where that flying saucer crashed in Roswell.

My mother was the marshland. My father was the railroad. I was born in 1876 after they met on Station Island. Some now say that I am a ghost town, sinking in the mud. Maybe I am, but I hate the name. So do the people who remember. They remember the independent spirit, the close friendships, the happy days and their paradise that was lost. ~ Drawbridge

It’s rare that you find a fully abandoned, 100% ghost town in the midst of one of the most urbanized areas in the country, but such is the case with Drawbridge, California. Near San Jose and flanked to the north by San Francisco and Oakland, Drawbridge is rarely visited despite being surrounded by millions of people. In fact, I lived in Oakland and never even knew about it. The reason for its low profile is a good one; Drawbridge is located in a salt marsh and sinking further into the mud with each high tide. It is also part of the Don Edwards San Francisco Bay National Wildlife Refuge, which is home to several endangered species and thus closed to the public. The refuge is patrolled by US Fish & Wildlife Service personnel, who I encountered on my trip while they were trying to apprehend some other “visitors.” Why didn’t I get busted? Because, through leveraging my vast City of Dust empire, I received legitimate access and could thus arrive via boat instead of taking the illegal and dangerous route.

Like so many other ghost towns, Drawbridge was brought to life by trains. In 1876, the South Pacific Coast Railroad built a two-room cabin for a bridge tender, Mr. Mundershietz, on a new stretch of line that by 1880 would link Alameda to Santa Cruz. The cabin was deep in marshland, between Coyote Slough and Warm Springs Slough, on a chunk of relatively solid ground soon known as Station Island. Because the train would stop at Station Island, people could now get there, and because there were lots of ducks around, it was hunters who first wanted to get there. The railroad even provided an old baggage car and chair car as free accommodation for hunters.

So it was that the earliest buildings in Drawbridge were gun clubs, and there were many of them. The first structure, after the bridge tender’s cabin, was the Gordon Gun Club, probably built in 1880. Incredibly, given the transience of wooden buildings in Drawbridge, I believe its ruins are captured in the b&w photo above, based on a shot from the 1980's, when it was still easily identifiable by its rounded Dutch roof and square nails.

After the Gordon Gun Club came The Sprig Duck Club, The Widgeon Gun Club, The Twilight Gun Club, The Tony Gun Club, and cabins with names like the Precata, Recreation, Harbor View, Sorry, Don’t Worry, Clambake Club, Julie Lodge, and more. As Drawbridge was often reached by boat, boat-building and repair was another typical pastime, as were swimming and fishing, naturally.

Some people actually lived in boats, known as “arks,” which were put up on pilings. One was a 50-person Matson Line lifeboat that had a cabin built in top of it. Drawbridge’s structures, all on pilings to stay dry when the tide came in, were along the railroad tracks, which became known as “Main Street” or “A Street.” Walkways were extended from front doors straight to the tracks, a privilege for which the railroad charged $1 a year. There were also “high tide parties,” when foot paths were flooded and neighbors would visit each other by boat. Toilets, unfortunately, went right into the marsh.

In 1902, the Sprung Hotel was established. As many as 500 people would come to Drawbridge each weekend, and Mrs. Sprung would often rent her own bed and sleep in the bathtub. In 1920, with the arrival of Prohibition, she made homebrew for 25 cents as quart, as well as wine. The Hunter’s Hotel was built by Louis Demit, also in 1902, and later run by his wife, Susan. Whether Louis died or the couple divorced is unknown. Despite being smaller than the Sprung, the Hunter’s Hotel had a large ballroom decorated with stuffed birds and windows all around. It also contained a baby grand piano.

As one man familiar with Drawbridge, William McCall, Sr., said, “You wouldn’t go down there if you weren’t a different breed of cat. It wasn’t the easiest place for access; every duck you got you worked for. And like those people that went down, they were in another world. They were completely away from civilization.” Or, as the last resident of Drawbridge, Charlie Luce, put it, “…it wasn’t a disease, that Drawbridge mud just calls to you!”

By 1926, about the peak of Drawbridge, there were 90 cabins and five passenger trains coming through each day. Later, rumors circulated that Drawbridge was filled with gangsters, gamblers, and prostitutes (with a roulette wheel at the Hunter's Hotel to decide which lady of the marshy night would be yours!), but it was mostly populated by doctors, dentists, and store owners, many with a passion for duck hunting. Even so, mothers on the north end of the island warned their children to stay away from the south, while the south considered the north “stuck up.” By the way, there really was a roulette wheel, but residents said the only thing wagered on was waterfowl.

Then Drawbridge began to sink more quickly as the surrounding sloughs were cut-off by dikes or drained. Wells for fresh drinking water had to be drilled deeper. Sewage from Bay communities began to foul the water around Drawbridge, and the ducks decided it was time to leave. Next the Great Depression arrived and, after that, vandalism. Newspapers began referring to Drawbridge as a ghost town, with cabins full of antiques simply left by their owners. This was not true, so signs were hung on cabins: “Please don’t shoot my house,” and “Dear thieves and vandals, Please do not break into this little house. It’s the only home we have.” Sadly, the signs didn’t always work.

The Sprung Hotel closed in 1930. It would finally collapse in 1968. Hunter’s Hotel burned in 1943, possibly from a spark off the cigar of then-owner, Barney Panella. So Barney constructed the only two-story building ever seen in Drawbridge on the site, complete with another ballroom and yet another baby grand piano. It would burn in 1984. Throughout the history of Drawbridge, fire has been perhaps the gravest danger, even surrounded as it is by water.

By 1940, only 50 cabins remained and the marsh was so polluted it could not be swum in. By the end of the decade, the sloughs were too silted-in to navigate. The years passed and there were more fires, some thought to be for insurance pay-outs. The train no longer stopped unless it was flagged down. In the 1960’s, partiers began to make the trek to Drawbridge. Some of these people, called “dopers” by residents, would try and stay in empty cabins only to be chased out with a shotgun or an ax. In 1970, the railroad station was torn down.

Yet some old-timers held on, until at last there were two. Nellie Irene Dollin, who had first come in 1910 and bought a place in 1932, left in 1974. Her house was broken into by two drunken kids one night while she was home with her granddaughter. She had no more trouble after firing her shotgun out the window, but the newly-christened “Shotgun Nellie” had had enough and moved to nearby Hayward. Charlie Luce visited Drawbridge in 1930, but didn’t go in on a cabin—The Sunset Club—until 1950. It was torched in 1964. Charlie and some friends bought another house and he began living in Drawbridge full-time with Quincy, his dog. He was bought out by the US Fish and Wildlife Service in 1979. His former home burned down in 1986.

These days Drawbridge is almost more liquid than land, a condition that will only accelerate as the rate of sea level rise increases. Everyone on this trip left wet, muddy, and cold…but happy. One iPhone was submerged (while in a hip pocket!), but at least no one drowned. People are still trying to have parties, too, and continuing to damage or destroy buildings, but now they're usually getting caught before the party even gets going. While it might appear that there are a lot of structures remaining, compared to what was here 20, 30, or 40 years ago there is relatively little. Hopefully, what's left will persist until Mother Nature fully reclaims what was once hers alone, and the ghost town in a salt marsh finally vanishes entirely into the mist of the San Francisco Bay.

Many thanks to the DESFBNWR USFWS for very graciously letting me access Drawbridge. The public (which also includes me, now) is asked to please obey the "No Trespassing" signs. That's the best way to protect Drawbridge and honor its history. A special thank you to D. Thomson for providing a boat and navigation skills and generally making it all happen. Virtually all information from this post came from "Drawbridge, California: A Hand-Me-Down History" by O.L. “Monty” Dewey. If only every ghost town had such a thorough and well-researched oral history written about it. Thanks again, D.T.!

Next time we’ll be back in New Mexico, but just where is a mystery to me as much anyone. Oh, and happy birthday to me! Finally getting a new City of Dust post up is a pretty good present to myself.

Shown above and at left is the post office, where around 1953 a Mrs. Balko was postmistress. Mrs. Fanny Brown took the position on April 20, 1968, staying until the post office closed in 1984 (possibly on November 2). I visited on December 12, 2015 and on Valentine's Day 2016 the old PO burned to the ground. Apparently someone was driving a pick-up with a BBQ grill in the back and hot coals became airborne. Numerous blazes were started, consuming a total of 1,083 acres in southeastern Roosevelt County, but at least no one was hurt and no other structures were damaged.

Shown above and at left is the post office, where around 1953 a Mrs. Balko was postmistress. Mrs. Fanny Brown took the position on April 20, 1968, staying until the post office closed in 1984 (possibly on November 2). I visited on December 12, 2015 and on Valentine's Day 2016 the old PO burned to the ground. Apparently someone was driving a pick-up with a BBQ grill in the back and hot coals became airborne. Numerous blazes were started, consuming a total of 1,083 acres in southeastern Roosevelt County, but at least no one was hurt and no other structures were damaged.

In the late 1920s, it's said that locomotive firemen who provided assistance shoveling coal to get freight trains up the long hill to

In the late 1920s, it's said that locomotive firemen who provided assistance shoveling coal to get freight trains up the long hill to