skip to main |

skip to sidebar

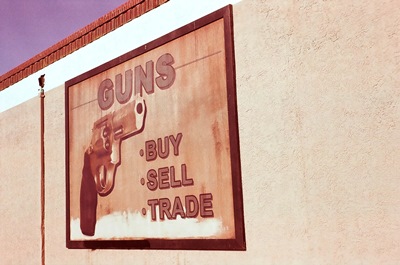

Clayton, New Mexico is a little bit out of the way. You’re probably not going to just suddenly stumble into it. Unless you’re going to visit the barren place where New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Texas all meet, in which case, sure, maybe you will happen across it.

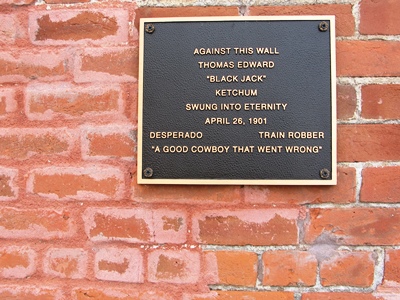

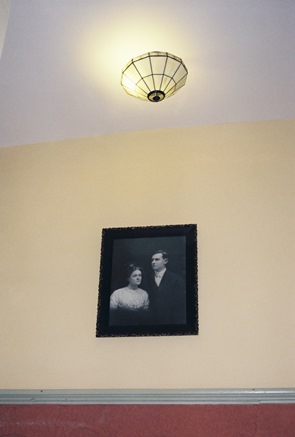

Despite its location, Clayton is famous for several things. There are lots of dinosaur footprints nearby. And a volcano, too. The lovely Eklund Hotel is there, established in 1892 and once the finest railroad hotel between Fort Worth and Denver. There are even two bullet holes still visible in the tin ceiling of the old saloon. That’s maybe not as impressive once you know that the shots were fired by excited supporters of President Warren G. Harding upon his election in 1920. Hey, no injuries were reported. But Clayton was also the site of what is widely agreed upon to be the most botched hanging in the West, that of Thomas Edward “Black Jack” Ketchum. I looked into it all on the frozen, windswept weekend before Thanksgiving while based at the Eklund.

(Above are the old headboards off the beds in the Eklund re-used as seat backs in the dining room.)

Black Jack was born in Texas and began leaving a trail of alleged crime in 1890, at age 27, right around the time he came to New Mexico. Possibly a soured love affair drove him off the rails. If so, crime must have already been in his genes because his older brother, Sam, left his wife and family to become an outlaw, as well. I say Black Jack’s crimes were “alleged,” because, while he was connected to many robberies and dark occurrences over the years, including the famous disappearance of politician Albert Jennings Fountain and his young son, Henry, near Las Cruces, he was never convicted of anything until being sentenced to death for attempting to rob a train. This was also unusual as no one else in American history was ever executed for train robbery alone.

because his older brother, Sam, left his wife and family to become an outlaw, as well. I say Black Jack’s crimes were “alleged,” because, while he was connected to many robberies and dark occurrences over the years, including the famous disappearance of politician Albert Jennings Fountain and his young son, Henry, near Las Cruces, he was never convicted of anything until being sentenced to death for attempting to rob a train. This was also unusual as no one else in American history was ever executed for train robbery alone.

Eventually Black Jack and his brother joined the dapper and charming Hole in the Wall Gang in the north-central part of the state, sometimes making a living ranching and, at other times, jockeying for position with Butch Cassidy’s other crew, the Wild Bunch.

On September 3, 1897, the Hole in the Wall Gang robbed a train between Folsom and Des Moines, NM. They did so again on July 11, 1899, but Black Jack did not participate in the second effort. After the second robbery, a gunfight ensued near Cimarron and Sam was badly wounded. A second shoot out occurred a few days later and a sheriff and deputy were killed. Sam was finally caught but died a short time later of his injuries in the Santa Fe Territorial Prison.

On August 16, 1899, Black Jack attempted to single-handedly rob the same train, unaware that his brother was recently dead from a similar idea. Black Jack boarded the engine, but mistakenly forced it to stop on a sharp turn where the cars with the loot could not be uncoupled. Meanwhile, the conductor, Frank Harrington, was getting sick of being robbed. He crept through the cars and shot at Black Jack, who returned fire. Black Jack missed; Harrington nearly severed Black Jack’s arm at the elbow. Black Jack fell off the train but was unable to get back on his horse.

The train quickly got moving again, leaving Black Jack to lie out all night until “help” arrived in the form of another train. He raised his gun as the conductor and brakeman approached him. They offered to shoot him right then if he wanted a fight, but he replied, "No boys, I am all done. Take me in." His arm was amputated in Trinidad, Colorado and then, restored to relative health, he was sent back to Clayton for trial. Convicted of “felonious assault upon a railway train,” Black Jack became the only person sentenced to death under the law, which was later overturned by the Supreme Court as carrying too severe a sentence.

Now, Clayton had never seen a hanging before and they weren’t quite sure what to do, besides sell tickets and tiny Black Jack dolls hanging from miniature gallows. The execution was delayed several times, but rumors of a plan to break Black Jack out of jail got a date finalized.

On April 26, 1901, after a further delay of several hours for continued fine-tuning of the gallows, Black Jack stood on the scaffold and these words are often said to have been his last: “I'll be in hell before you start breakfast, boys! Let her rip!” However, they’re probably apocryphal; he was executed around 1 p.m., closer to lunchtime anyway. The San Francisco Chronicle reported that Black Jack was somewhat more subdued, his legs trembling, saying only: "Good-by. Please dig my grave very deep. All right; hurry up." Still other accounts have simply, “Hurry up boys, get this over with.”

Whatever he said, Black Jack clearly wanted it all over with fast. The sheriff needed two swings of the hatchet to cut the rope, but the trap finally fell open and Black Jack dropped. However, the rope was too long and, possibly due to over-testing with a 200-pound sandbag, no longer had any elasticity. Thus, Black Jack was instantly decapitated, one of only three such occurrences over a few hundred years of recorded judicial hangings in the U.S. and Europe.

Photos exist of the gruesome aftermath, the separated head still contained in the black hood and lying in front of the one-armed corpse. The Chronicle noted that the heart clearly continued beating for awhile. Then, in another strange twist, Black Jack’s head was sewn back on his body before burial at 2:30 p.m. that day in Clayton’s Boothill. One wonders how much effort they put into the job. No one was ever executed in all of Union County again.

Photos exist of the gruesome aftermath, the separated head still contained in the black hood and lying in front of the one-armed corpse. The Chronicle noted that the heart clearly continued beating for awhile. Then, in another strange twist, Black Jack’s head was sewn back on his body before burial at 2:30 p.m. that day in Clayton’s Boothill. One wonders how much effort they put into the job. No one was ever executed in all of Union County again.

Black Jack's grave was moved from the original Boothill to the current Clayton Cemetery in the 1930's. In the end, he got Shakespeare for an epitaph and still gets flowers over 100 years after his death. We should all be so lucky.

“And How His Audit Stands, Who Knows Save Heaven.”

The story or Thomas "Black Jack" Ketchum is widespread on the internet, although inaccuracies abound. Legends of America does a nice job and Allflictor.com reprints the San Francisco Chronicle article. Wikipedia isn’t bad either. Perhaps the oddest piece is at badhombres.com, where Black Jack’s great, great nephew provides history and insight found nowhere else. Whether it’s all true is anyone’s guess.

FEBRUARY 2014 UPDATE: Here at City of Dust we're always trying to get the story straight. Any research into Black Jack Ketchum's hanging will turn up a variety of quotations from his final moments and I went to some pains trying to sort out what he actually said. I believe his intended last words really were, "Goodbye, please dig my grave very deep. All right, hurry up." However, truth is always stranger than fiction and, in fact, Black Jack Ketchum seems to have said almost everything attributed to him and then some, just not all of it from the gallows.

The most famous and widely-quoted statement is, "I’ll be in hell before you start breakfast, boys! Let her rip!" That's almost correct. But it was not said immediately before he dropped and it was mostly not intended for just any "boys." The first part of the quotation appears in the Santa Fe New Mexican, dated April 26, 1901, the day of the hanging, and it is directed toward Frank Harrington, the conductor who shot Black Jack's arm off. When Ketchum's lawyer was leaving his cell for presumably the last time, Black Jack told him, "Say, tell Harrington I'll meet him in hell for breakfast." This was after he'd requested to "be buried face down so Harrington can kiss my ass." The next morning, according to the New Mexican, he told Sheriff Garcia to "hurry up the hanging so he could get to hell in time for dinner."

The first part of the quotation appears in the Santa Fe New Mexican, dated April 26, 1901, the day of the hanging, and it is directed toward Frank Harrington, the conductor who shot Black Jack's arm off. When Ketchum's lawyer was leaving his cell for presumably the last time, Black Jack told him, "Say, tell Harrington I'll meet him in hell for breakfast." This was after he'd requested to "be buried face down so Harrington can kiss my ass." The next morning, according to the New Mexican, he told Sheriff Garcia to "hurry up the hanging so he could get to hell in time for dinner."

The other part of the quotation comes from what truly were Black Jack's last words. Sheriff Garcia, apparently drunk, was having a hard time cutting the rope to open the gallows doors. The New Mexican records that Ketchum, nervous and impatient, said, "Let 'er go, boys. Let 'er go." It is said that Garcia's friend, Dick Franz, finally cut the rope and became a minor celebrity for it afterward.

Apparently Ketchum's headless body landed on its feet and even remained upright for a moment, spurting blood. Sheriff John McCandlass, visiting from Dalhart, Texas, held the corpse to the ground to stop the convulsions that followed. Five minutes is reportedly how long Black Jack's heart continued beating.

You probably didn't need to know all that. But you might be interested to know that Black Jack wrote a letter to President McKinley saying that innocent men were imprisoned for a robbery that Ketchum and his gang had committed at Steins Pass. He wouldn't say a word as to where his compatriots were at that time but maintained that he had never killed anyone and was a victim of mistaken identity, having been confused with another outlaw, Black Jack Christian, killed four years earlier. His last requests were music and female companionship. The former he received via violin and guitar. The latter was denied due to a lack of public funds with which to pay the companion. It was said that he did at least eat a hearty final dinner.

Oh, and his request to be buried face down? When Black Jack was exhumed in 1933 to be moved to the new Clayton cemetery his coffin was opened and it was found that this, too, had been denied. Then, as a final addendum, Teddy Roosevelt was presented with his Winchester 30-30 for some reason that I can't quite figure out.

Where did I find all this information? From what's probably the most complete and accurate description of Black Jack Ketchum's final days, Death on the Gallows: The Story of Legal Hangings in New Mexico, 1847-1923. There is also an informative unofficial brochure on Thomas Edward Ketchum written by Jerry Phillips that you can find around Clayton. I guess some stuff still hasn't quite made it to the internet.

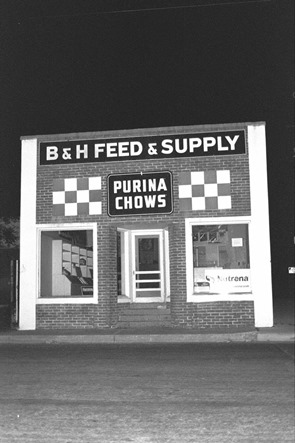

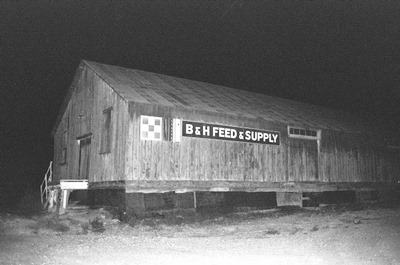

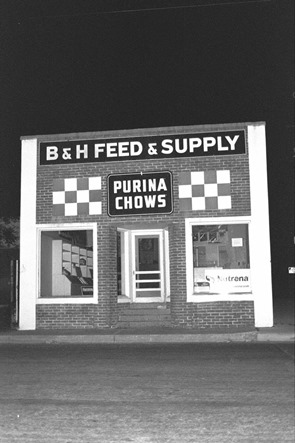

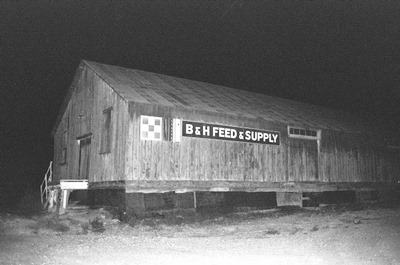

The photos of B H Feed & Supply were taken one night in late 2005. The shop is now the home of Crossroads Coffee Mill, a wonderful place for coffee and whatever else you might need of a morning. Be sure and stop by next time you're in Clayton. Tell them City of Dust sent you.

While the Man with No Name might feel right at home in the ghost town of Riley, he and the town might not fully understand each other. That’s because, unlike Sergio Leone’s laconic anti-hero, Riley has two names. Even though the isolated enclave along the oft-dry banks of the Rio Salado was already known as Riley when the post office opened in 1890, many old timers still refer to it by its original name of Santa Rita, bestowed in 1880 when it was a small colony of homesteaded farms established by Mexican-Americans. Riley, it turns out, was the name of a local sheep ranch owner. Maybe there was some sort of naming conflict amongst various livestock factions.

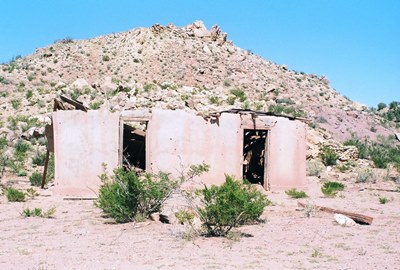

As with any New Mexican ghost town worth its salero, Riley was once a hotbed of mining activity with four active mines pulling coal and manganese out of the dry and dusty earth. By 1897, about 150 people lived in Riley and there were two stores and a stone school (pictured in the two shots above).

While, as has happened to so many ghost towns, the mines eventually did stop paying out, it wasn’t that which ultimately caused Riley’s demise. In fact, the water table dropped due to drought and overgrazing, rendering irrigation tough and farming a losing proposition. Without mining and farming, there wasn’t much else to keep a body busy. In 1931, after 41 years, the post office closed up and that was the end of Riley. Almost.

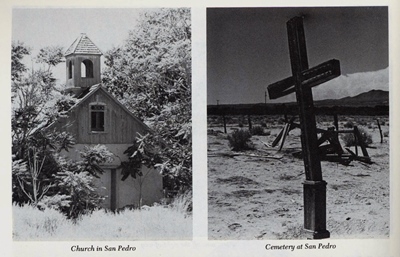

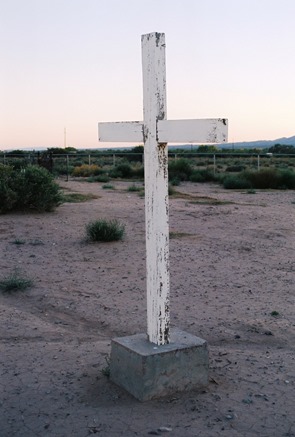

You see, there is one building that is carefully maintained in Riley: the Santa Rita Church (shown above). Each year on May 22, the Feast Day of Santa Rita, those with ties to the old community come back together and a priest says Mass at the little church. There is a picnic afterward. It must really be something to be a part of. Of course, even at its most bustling the priest only stopped in Riley once every four months.

Riley can be accessed by gravel roads from either the north or south. From the north, you can start at the non-existent town of Bernardo and loop way out around Ladron (i.e, “Thief”) Peak. From the south, you have to drive through the Cibola National Forest and cross the Rio Salado. Either route takes you through a vast and spectacular landscape.

However, while it’s often said that this drive is “easy” by New Mexican off-road standards, both times I’ve been through were touch and go. The first time the Rio Salado was almost uncrossable, not because it was running, but because the north bank had collapsed. This last time would’ve actually been impossible, but following a torrential monsoon the Army Corps of Engineers had just been through and re-graded the whole stretch for us. How nice of them!

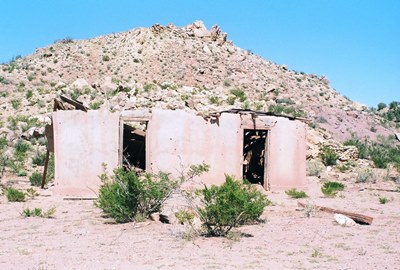

I scavenged both Philip Varney and Linda Harris for this one. Varney mentions “five roofless adobes” in his piece on Riley. You’d be hard-pressed to find that many now, but the shot above does show one of the last hold-outs, still sans roof. Below is the view of Riley from the southern approach.

Happy holidays everyone! Next post will be a surprise…to me as much as anyone.

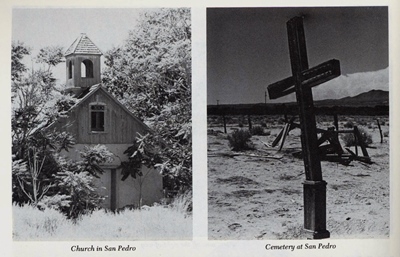

There are two ghost towns by the name of San Pedro in New Mexico. One is a former gold mining town to the north, in Santa Fe County, but, since we’re still roaming around U.S. Highway 380 in the central part of the state, we’ll check out the one in Socorro County.

When Philip Varney visited San Pedro in the late-‘70s, he described a ghost town of more than a dozen buildings, including the wood and adobe San Pedro Catholic Church, complete with intact steeple, and another large adobe structure, once the home of a well-known landowner. Things have changed a bit over the last 30+ years and, while not exactly a booming metropolis, San Pedro is a little livelier than when Varney came through. Kinda like Chloride, but without the museum.

While there might be more actual residents these days (and perhaps meaner dogs, as well), there seems to be fewer buildings. The church is nowhere to be found, nor is the neighboring barbershop. The stately adobe residence has mostly sunk into the earth (and is guarded by one or two of the aforementioned pups). The schoolhouse, pictured at top, still remains though. Built by the W.P.A. in 1936, it closed shortly thereafter and is now owned by the family living next to it. They were kind enough to let me take a photo after finding me basically standing in their driveway when they came home one evening. Thanks, folks!

San Pedro was settled in the mid-1800s by two families, the Montoya’s and the Tefoya’s. By 1860, the town had a population of 223. At that time, the village, located on the east bank of the Rio Grande and close to El Camino Real, was a Spanish agricultural settlement known especially for its grapes. These grapes were crushed into wine reportedly shipped “all the way to Kansas.” The village was also a resting place and trading center for travelers on El Camino Real. Later, some residents became miners and worked in nearby Carthage and Tokay. Apparently, a heated baseball rivalry developed between the San Pedro and Tokay teams with a third forgotten community, Bosquecito, also in the mix.

located on the east bank of the Rio Grande and close to El Camino Real, was a Spanish agricultural settlement known especially for its grapes. These grapes were crushed into wine reportedly shipped “all the way to Kansas.” The village was also a resting place and trading center for travelers on El Camino Real. Later, some residents became miners and worked in nearby Carthage and Tokay. Apparently, a heated baseball rivalry developed between the San Pedro and Tokay teams with a third forgotten community, Bosquecito, also in the mix.

The Rio Grande, that lifeblood of San Pedro--as it was for so many small towns--was the reason for San Pedro’s location and, finally, a major reason for its decline. All that remains of the section of the river that used to pass beside San Pedro is a dry, sandy bed, the result of canals that have shifted the course of the waterway almost a mile to the west.

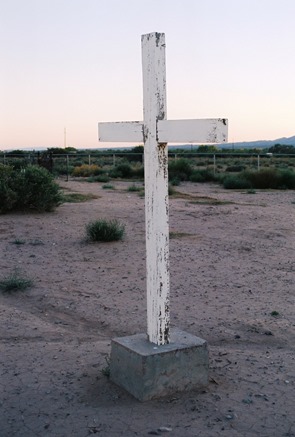

Varney described the San Pedro Cemetery as “windswept and desolate.” I love a nice, desolate, windswept cemetery, but in San Pedro the cemetery, too, has been modernized. A comparison of grave markers shows them to have been upgraded since Varney’s visit. While I have to admit that I prefer desolation, aesthetically-speaking, I’m happy for San Pedro. And I got in some desolate, windswept cemetery viewing in cold, cold Clayton last weekend.

We’ll get to Clayton and its famous decapitated dead man, Black Jack Ketchum, eventually, but we’re going to stay in sprawling Socorro County and head down to the banks of the Rio Salado to visit Riley (aka Santa Rita) next. Until then, be well, as both Garrison Keillor and Walgreens tell me these days.

Information for this post (and the b&w photos above) came from Philip Varney, of course. Additional help was courtesy of ghosttowns.com and, through them, Roadside New Mexico: A Guide to Historic Markers, Revised and Expanded Edition!

Last post we visited San Antonio, New Mexico, the spiritual home of the Hilton Hotels chain. San Antonio experienced a boom when coal mines ramped up production in Carthage, about 10 miles east. One of those early mines, the “Hilton,” was owned by August H. “Gus” Hilton. But, while San Antonio is still pretty hard to miss, especially if you’re looking for cranes at Bosque del Apache, three towns closely linked to San Antonio—Carthage, Tokay, and Frailey—have sunk deep into oblivion. In fact, even the true spelling of “Frailey” has been lost. You might see it referred to as “Fraley” or “Farlay” and either might be right. One spelling that is probably not correct is the one found on the NM Historic Marker beside nearby Highway 380, which has it as “Farley.” At top is what might have once been part of an auto garage, judging by nearby remains.

Carthage was the site of the first coal mine in New Mexico, the Government mine, which employed U.S. Army soldiers in the early 1860’s and supplied Forts Bayard, Selden, and Stanton. Construction of a railway to ship coal to San Antonio from Carthage began on March 1 of the year that seems to represent the zenith of the Wild West, 1881, when Billy the Kid died and there was a Gunfight at the O.K. Corral. I think the shot above might be the bottom of a tower used for watering locomotives.

The Santa Fe Railroad Co. finished a bridge across the Rio Grande in 1883 and, by 1889, Carthage topped the list of coal camps in the state with a population of about 300. But, by 1893, coal production was lagging, so the Santa Fe Railroad Co. made a deal to move the entire town to Cerrillos, NM. On August 17, 1893, the Old Abe Eagle reported, “…All the dwelling houses, coal chutes and machinery have already been moved. The place has practically been razed to the earth and the depot, adobe hotel and Gross, Blackwell and Co. are about all that remain.” The Santa Fe Railroad then promptly went into receivership on Christmas Eve. Almost two years later it would re-emerge as the famous Atchison, Topeka, and Santa Fe (AT&SF).

From 1894, coal extraction continued while mines changed hands and changed hands again. The abandoned Santa Fe Railroad Co. line finally ceased operating entirely in 1896 and then everyone spent some years trying to figure out how to get the railroad to run those 10 miles to San Antonio again. The difficulties of (re)building the short spur came to a head in 1905 when competing mining and railroad interests sued each other. Mining ceased for two years during the litigating. Finally, the case was settled out of court, 50 new miner’s homes were quickly built by the Carthage Coal Company, and production surged.

Then, on New Year’s Eve 1907, there was a massive explosion in the Bernal mine which killed nine miners, throwing two 300 yards from the site. Two more were seriously injured. It was said that many more would’ve been killed if it weren’t for the fact that the accident occurred during lunch and most men were eating. A somewhat lesser disaster struck Carthage on February 22, 1918, when coal dust ignited in the Government mine, killing one mine inspector who improperly used his safety equipment and a sparrow.

Mining continued for decades, but eventually with diminishing returns. The last train left Carthage on August 28, 1931. After that, things were really on the downswing, although serious mining interests struggled through into the 1940’s. The last mine, Tres Hermanos, was opened in 1980 by Cactus Industries. It was closed by 1981.

Now, if you look at the entry for Carthage on ghostowns.com, you will see a note dated April 2, 2000 which laments that most of what had remained of Carthage--apparently a fair amount--had recently been hauled off to a nearby dump. The “clean-up” was ostensibly part of a “desert restoration project” and, while I sure love the desert, I find this a little hard to believe. There is so much wide-open space in every direction out here that restoring this small area strikes me as bizarre. Not impossible though. On the other hand, “Ghost Towns and Mining Camps of New Mexico” stated in 1975: “Today what is left of Carthage is fast melting into oblivion.” Other than the impressive adobe ruins of the large home of a mine superintendent, John Hart, who left Carthage in the mid-1940’s, I have no idea what’s really been lost in the interim. At least the corpse of the small mining car above persists.

The “clean-up” was ostensibly part of a “desert restoration project” and, while I sure love the desert, I find this a little hard to believe. There is so much wide-open space in every direction out here that restoring this small area strikes me as bizarre. Not impossible though. On the other hand, “Ghost Towns and Mining Camps of New Mexico” stated in 1975: “Today what is left of Carthage is fast melting into oblivion.” Other than the impressive adobe ruins of the large home of a mine superintendent, John Hart, who left Carthage in the mid-1940’s, I have no idea what’s really been lost in the interim. At least the corpse of the small mining car above persists.

Whether Carthage disappeared recently or long ago, what remains now is hard to identify. Millions of pieces of broken glass glitter in the sun, a surprising percentage of them pink and purple. (So much for a restoration, eh?) A few stone foundations can be seen here and there. Several old mines can be located, all sealed and capped. Walking the raised rail trestle from the relatively intact Carthage Cemetery, it’s unclear where Carthage becomes Frailey, the site of a limestone quarry and kilns owned by Mr. J.B. Frailey, once the trainmaster at San Marcial, now also a ghostly town.

Then there’s Tokay, founded in 1918 by Bartley Hoyt Kinney, Sr., who was involved in the Carthage mines and organized the San Antonio New Mexico Coal Company. He wanted to name the town “Kinney,” but the post office refused. Finally, while talking to the postal inspector at Mr. Kinney’s general store, he saw a box of Tokay grapes and said, “How about Tokay?”

Tokay actually struggled into the late-1940’s, but eventually mining ceased and its structures were moved to Socorro. It would’ve been around here somewhere. But where? Who knows anymore? Just a few miles southeast is the Trinity Test Site, where, on July 16, 1945, the first atomic bomb was detonated. Carthage, Tokay, and Frailey, once sizable and active places, couldn’t be much more obliterated if they’d been at ground zero.

Hey, even Philip Varney didn’t have much to say about these three towns. There’s little to be found on Carthage, but, surprise, surprise, there is one scholarly article, “Mining History of the Carthage Coal Field, Socorro County, New Mexico.” It’s the best source, by far. I also consulted the aforementioned ghostowns.com. Even less can be found on Tokay and Frailey and what I managed to unearth was part of a good history of the railroad in the area formerly posted at New Mexico Wanderings. Old newspaper articles on the mine explosion can be found at gendisasters. And let's not forget Ghost Towns and Mining Camps of New Mexico by James E. and Barbara H. Sherman.

Next time, we’ll make a quick stop at San Pedro, just between Carthage and San Antonio.

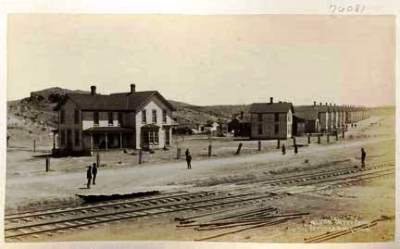

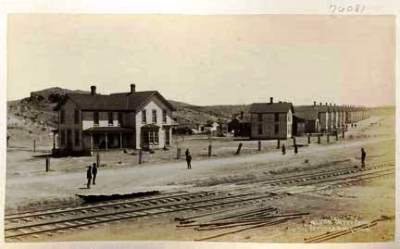

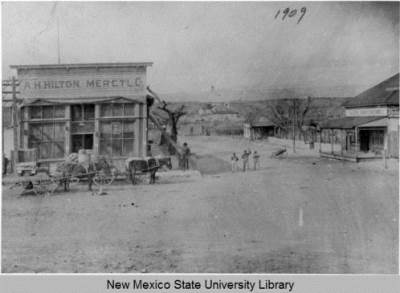

Around the turn of the 20th Century, a boy would walk from his father’s mercantile store, which also served as a hotel, to the train depot (shown above), just a short distance away. This boy then carried the luggage of passengers newly arrived in San Antonio, New Mexico back to their rooms, which ran $2.50 a day and included meals. The boy met every train stopping in town, regardless of time or weather. In 1919, that boy, Conrad Hilton, now thirty-two years old, bought the Mobley Hotel in Cisco, Texas and thus began the Hilton Hotels chain. Paris Hilton is his great-granddaughter.

Below is a shot of some almost 100-year-old graffiti from inside the depot. Note the infinity sign/hat brim. Could it be the mark of the original train-hopping Bozo Texino?

San Antonio can trace its history back to 1629 and the founding of the San Antonio de Senecú Mission. The Apaches succeeded in destroying the mission in 1675 and for over 100 years the burnt remains of the village, which had been inhabited by Piro Indians for a mere 700 years prior, slowly decayed out on the plains, a caution to travelers on the nearby Camino Real. Now those ruins have been fully reclaimed by nature and the exact location of San Antonio de Senecú is unknown. On the other hand, the Crystal Palace, below, was once a dance hall and then a much more dilapidated (and photogenic) auto garage, but someone eventually decided to kinda fix it up.

Hispanic farmers from northern New Mexico established present-day San Antonio in 1820 and, when the Santa Fe Railroad arrived in 1880, the town shifted to be closer to the rails. While most of San Antonio’s 1,250 residents still raised livestock, made wine, or even kept bees, the railroad was soon extended 10 miles east to reach the coal mines of Carthage and Tokay. Stakes included a claim known as the Hilton Mine, owned by A.H. “Gus” Hilton, who used the money to found the A.H. Hilton Mercantile Store. Mr. Hilton’s son, Conrad, was born on Christmas Day, 1887.

For almost 50 years the mines paid out, the trains came and went, and stagecoaches ran between White Oaks, Fort Stanton, and Lincoln. However, by 1925, the mines were going bust and the railroad soon took up its tracks. Then two major floods in 1929 washed away a big chunk of the town and the surrounding farmland. WWII lured away most remaining young men and A.H. Hilton’s original mercantile burnt around the same time, which, incidentally, pretty much coincided with Conrad's marriage to Zsa Zsa Gabor. However, Hilton’s wooden bar was saved and installed in the famous Owl Bar and Restaurant in 1945, where it is used to this day to support Tecate and green chile cheeseburgers. The Owl Bar itself was built by Brunswick Balke Collender Company. You might have used their bowling balls.

Then two major floods in 1929 washed away a big chunk of the town and the surrounding farmland. WWII lured away most remaining young men and A.H. Hilton’s original mercantile burnt around the same time, which, incidentally, pretty much coincided with Conrad's marriage to Zsa Zsa Gabor. However, Hilton’s wooden bar was saved and installed in the famous Owl Bar and Restaurant in 1945, where it is used to this day to support Tecate and green chile cheeseburgers. The Owl Bar itself was built by Brunswick Balke Collender Company. You might have used their bowling balls.

And that is largely where San Antonio is at today, except for the slight shift to the north, where most business is now conducted along U.S. 380. Not a true ghost town, you still won’t find any trains stopping at the marooned and badly listing depot. Of course, every ghost town aficionado hopes to discover something new, and, while it’s well-known that all that’s left of what could be considered the original Hilton Hotel is its foundation, located across from the old post office (now a restored private residence), I have been unable to find a single picture of the site anywhere. So, as is my wont, I took my own. In fact, I took two. The concrete shown here and below is all that remains of the birthplace of one of the greatest hotel chains in the world, without which Paris Hilton might be living in a trailer out in the Socorro County desert. However, the original ballroom floor from the hotel was reportedly installed in the Wool Warehouse building in Magdalena. It must've been part of a remodeling job as that place was built in 1913. Can anyone get me in to have a look?!

while it’s well-known that all that’s left of what could be considered the original Hilton Hotel is its foundation, located across from the old post office (now a restored private residence), I have been unable to find a single picture of the site anywhere. So, as is my wont, I took my own. In fact, I took two. The concrete shown here and below is all that remains of the birthplace of one of the greatest hotel chains in the world, without which Paris Hilton might be living in a trailer out in the Socorro County desert. However, the original ballroom floor from the hotel was reportedly installed in the Wool Warehouse building in Magdalena. It must've been part of a remodeling job as that place was built in 1913. Can anyone get me in to have a look?!

For those Paris Hilton fans wishing to tour the old ruins, I can be hired at a very reasonable price. Please wear sensible shoes and long pants and don’t expect much.

Info for this post came from Varney and Harris. Special thanks to the grandson of the owners of the San Antonio depot for the quick peak inside. Next time we’ll visit the aforementioned Carthage and Tokay. Or, at least, an area the might as well be.

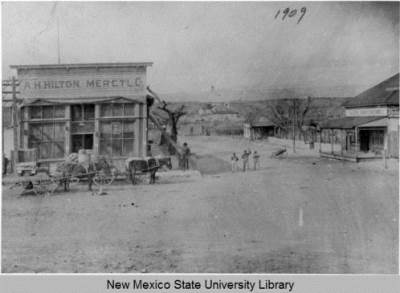

APRIL 2014 UPDATE: Thanks to Jerrysocorro P, a wonderful photo of the A.H. Hilton Merctl Co building has been brought to my attention. Apparently taken in 1909, this is a rare image indeed. It shows the corner on which the above ruins were photographed. Across the street is a building signed as "City Drug Store." This is what was later the post office and still stands as a private residence.

Very interesting to me is the building behind the mercantile. Unfortunately, you can't see it on the downloaded photo, but behind the skeletal tree is a sign on which you can read " OT L". The best way to have a look for yourself is to go to this page. Is this another "Hilton Hotel"? I can't imagine San Antonio supporting two hotels when it couldn't support a bank.

This excellent biography (thanks again, Jerrysocorro P!) on Conrad Hilton mentions a "makeshift hotel" where for $1 you got a room and a hot meal. It also specifically states that there were rooms in the mercantile, although the merc looks rather un-hotel-like. So what is this second apparent hotel? 'Tis a mystery.

Kudos to the University of New Mexico and NMSU for making historical photos like this one available on-line.

Because I only manage a "real" post here once or twice a month, I've created a City of Dust page on Facebook. I will try to add a new ghost town or abandonment photo every day and, while most of the shots will be from New Mexico, I'm sure I'll get distracted every now and then. I hope this Facebook page might spur more discussion and interaction, as well. There's lots of stuff I'd like to know about the places I shoot and now it'll be easier for folks to tell me. However, never fear, this blog will always remain my bread and butter. If you want to have a look at the Facebook page, go HERE.

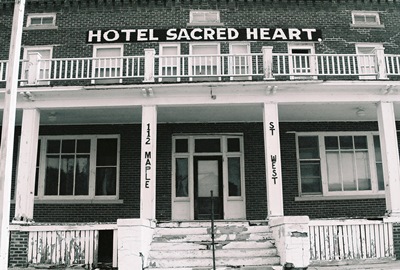

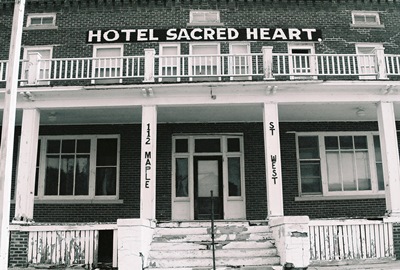

Speaking of getting distracted, below is a haunted house just in time for Halloween. This was taken in September in Sacred Heart, Minnesota, way out on the prairie. The photo above was also taken in Sacred Heart, believe it or not.

The next post here should be on San Antonio, New Mexico, from where the line runs directly down the old railroad tracks to...Paris Hilton. Until then, thanks for your interest and Happy Halloween!

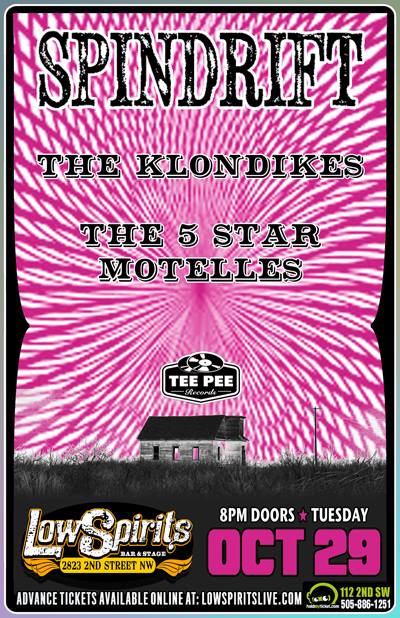

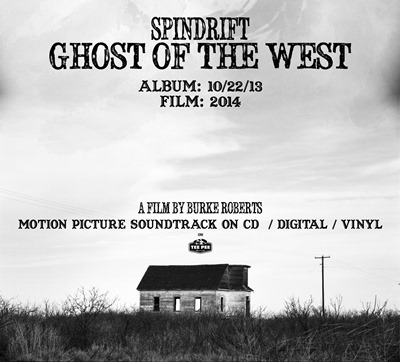

We interrupt our regularly scheduled program to mention that Spindrift’s fantastic new album, Ghost of the West, was released today. The band is a totally compelling blend of Tex Ritter, Ennio Morricone, Pink Floyd, and Hawkind. When was the last time you heard something like that? To listen to a sample track, visit this recent piece at the Onion’s A.V. Club.

While you’d want to buy the record just for the music, I personally think the cover art is kinda cool, too. Yup, that’s the First Presbyterian Church of Taiban. While I might consider letting almost any band use one of my photos (well, except Foreigner or the Eagles), it sure makes things nicer when the band in question is one of such quality and style. Not to mention, their interest in the West is real. This will become even clearer when a DVD of their 2012 Ghost Town Tour is released next year. Did I mention the album is on vinyl, too? Check Tee Pee Records, Amazon, etc.

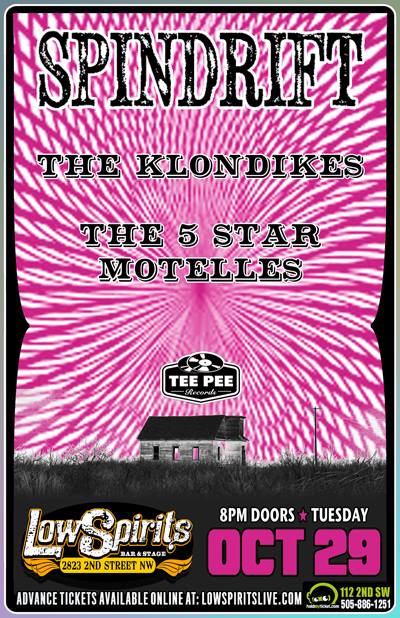

Also, for those of us in Albuquerque, Spindrift is playing Low Spirits next Tuesday, October 29. See ya there.

With a population of 1,956 as of the 2012 census, Gamerco, New Mexico might be the biggest town we’ve ever featured on City of Dust. It ain’t a ghost town, that’s for sure. But it’s also lost its original reason for existing: coal. Gamerco is actually an acronym for the Gallup American Coal Company, which operated area coal mines for two years before lending its name in 1922 to the town developing around its operations.

At one point, five hundred miners and their families lived and worked in Gamerco and reportedly loved it. The company took care of them by paying well, ensuring a safe workplace, and keeping hours reasonable. Along with the processing and power plants and the rail spur needed for its day-to-day business, GAMERCO built homes and apartments for its employees, as well as a church. Workers even passed on unionizing figuring things couldn’t get much better. Well, those days seem to be long gone most everywhere and for Gamerco they left in the 1960’s. That was when the company closed its mines, shuttered the power plant, and moved the rail spur.

People still live in some of the old residences and in the former Gamerco offices. I badly wanted to explore the old plant, but a group of people seemed to be living in a trailer out back there, too. Someone might have also been living inside the plant. In any case, I figured I wouldn’t go down and say “hello.”

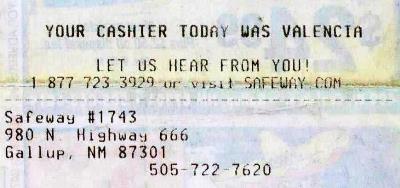

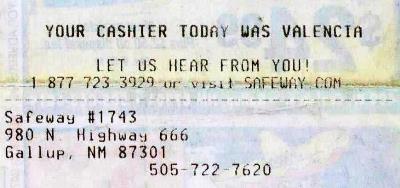

Gamerco used to be just off U.S. Route 666, the “Devil’s Highway,” but that treacherous stretch of road was renamed U.S. Route 491 in 2003. Although, I believe it’s still just as treacherous. Happily, the Safeway in Gallup still hasn't got the memo. Without any coal, Gamerco’s most well-known export is perhaps Onawa Lacy, Miss New Mexico 2006 and a competitor in the Miss USA pageant. The town might soon be annexed by Gallup. Whether that means Gamerco will then lose its name, too, who can say?

Gamerco used to be just off U.S. Route 666, the “Devil’s Highway,” but that treacherous stretch of road was renamed U.S. Route 491 in 2003. Although, I believe it’s still just as treacherous. Happily, the Safeway in Gallup still hasn't got the memo. Without any coal, Gamerco’s most well-known export is perhaps Onawa Lacy, Miss New Mexico 2006 and a competitor in the Miss USA pageant. The town might soon be annexed by Gallup. Whether that means Gamerco will then lose its name, too, who can say?

Gamerco was good enough for Philip Varney, so it’s good enough for us! Other information came from Gamerco’s Wikipedia page. Ghosttowns.com also has an entry and some photos. Beyond that, there just isn't much out there on the old town.

Until next time.

It’s seems like it’s been a very long time since I’ve done a proper post, but I guess it’s only been a month. In that time I’ve been conducting experiments in exhaustion. I like to do this from time to time even though the results are always the same: Days begin to feel like lifetimes, I become very forgetful, and then I get sick. So, here I sit with a cup of a homeopathic Thera-Flu-like drink that will probably have me nodding off at the keyboard while I try to remember where I was in late-July, which might as well have been the 1980’s for how recent it feels now.

Anyway, occasionally City of Dust likes to head further out on the road than usual. Over the past few years we’ve been to Hungary, Germany, and Cambodia. While Alaska might not sound quite as exotic to a North American, it sure feels pretty exotic when you’re there. Sort of like living in Jurassic Park but instead of dinosaurs you get eaten by grizzly bears or trampled by moose and go crazy because the sun never sets. While lots of buildings look derelict, I didn’t find much that was truly abandoned to explore. Probably because the cruel winter destroys anything that’s not regularly tended, unlike out here in the desert. For a while I thought the only thing I might have to report on was the over-the-top level of public intoxication I witnessed in Fairbanks. But then I found an abandoned igloo.

Large enough to be seen from planes at 30,000 feet, the Igloo City Hotel, conceived as a tribute to the Inuit people and built by a man named Leon Smith, was clearly a beautiful idea. Four stories tall and made of concrete--not ice--with a lovely mountain backdrop, the only flaw in the plan might’ve been building the place 180 miles from Anchorage and almost the same distance from Fairbanks. In fact, it’s way out there on the George Parks Highway, 20 miles from Cantwell (pop. 222), the nearest town. While there is a relatively constant (for Alaska) stream of traffic traveling between Anchorage and Fairbanks, staying at this hotel would’ve put you in proximity to the now-also-abandoned gas station across the parking lot and not much else in the way of civilization.

Four stories tall and made of concrete--not ice--with a lovely mountain backdrop, the only flaw in the plan might’ve been building the place 180 miles from Anchorage and almost the same distance from Fairbanks. In fact, it’s way out there on the George Parks Highway, 20 miles from Cantwell (pop. 222), the nearest town. While there is a relatively constant (for Alaska) stream of traffic traveling between Anchorage and Fairbanks, staying at this hotel would’ve put you in proximity to the now-also-abandoned gas station across the parking lot and not much else in the way of civilization.

The structure was never close to being completed and the interior is just bare ribs made of hundreds of 2” x 4”’s, which I couldn’t see during my visit because there was nothing but darkness when I poked my head through a loose board. Mr. Smith apparently violated building codes by making the windows too small, started to run out of money, and then was hit by rising fuel costs even before the business itself had a chance of failing. But beyond the tiny windows the structure must’ve been otherwise well-built; the Igloo City Hotel was begun in the 1970’s and has now survived, vacant and exposed, for possibly over 40 Alaskan winters.

Of course, one man’s dream is…another man’s dream, also, and the Igloo City Hotel was sold a few times only to end up back in Smith’s hands after buyers missed their payments. Before dying, Smith, in failing health and concerned for his wife’s future, finally sold the property to Brad Fisher of Fisher’s Fuel Inc., who didn't actually want it. After Smith accepted his lowball offer, Fisher remembers thinking, "Oh no, that's not really what I wanted to happen!"

Fisher did end up operating the gas station and some adjacent cabins while trying to renovate the hotel, but finally ran out of money himself in the early 2000’s. The gas station and cabins were shuttered in 2005. Mr. Fisher now also has Igloo City, the old gas station, and the surrounding 38 acres up for bid, but will only sell to someone serious about completing the decades-old project.

Hopefully, an enterprising individual will buy the place and give it another chance. Word is that most locals consider it something of a landmark and someday I’d sure like to spend a night in Igloo City. I'd probably need the rest.

The full story of Leon Smith and his vision of an igloo-shaped hotel in the Alaskan wilderness may forever go untold. But most of the basics have been repeated on several websites that have featured Igloo City, although there are some errors that have proliferated. The best source on the history of the hotel is a STORY from earlier this year in the Alaska Dispatch, which features the quote from Mr. Fisher used above. If you’d like to see the wooden inside of the igloo, Kuriositas has a nice collection of shots.

I wanted to break into our regularly scheduled programming for a moment to mention that I was recently invited to contribute to Duke City Fix, a website exploring all things Albuquerque. My first piece several weeks ago was a re-working (read: shortening) of an epic post I did in early 2010 on the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Rail Yards, by far my favorite place to photograph in the city. I followed that up with a companion piece on the WHEELS Museum, a great repository of rail and transportation history and the only actual tenant at the rail yards. My third article, a recounting of a Sunday morning stroll down a battered yet still enthralling Route 66, was published ten days ago. I'm kicking ideas around for the next bit. Let me know if you have any suggestions.

The content of these can be a little different than what I do here, but you’ll still recognize the, uh, aesthetic, I think. If you’re interested in reading more, just follow the links in the text above (2020 UPDATE: Links are long dead). The WHEELS piece features the finest picture of an antique milk truck that I've ever taken. I’d like to thank Duke City Fix for the opportunity. I’m honored to be involved.

The next post will be a one-off stop in Alaska to take a look at a bit of entrepreneurial failure. Seriously.

because his older brother, Sam, left his wife and family to become an outlaw, as well. I say Black Jack’s crimes were “alleged,” because, while he was connected to many robberies and dark occurrences over the years, including the famous disappearance of politician Albert Jennings Fountain and his young son, Henry, near Las Cruces, he was never convicted of anything until being sentenced to death for attempting to rob a train. This was also unusual as no one else in American history was ever executed for train robbery alone.

because his older brother, Sam, left his wife and family to become an outlaw, as well. I say Black Jack’s crimes were “alleged,” because, while he was connected to many robberies and dark occurrences over the years, including the famous disappearance of politician Albert Jennings Fountain and his young son, Henry, near Las Cruces, he was never convicted of anything until being sentenced to death for attempting to rob a train. This was also unusual as no one else in American history was ever executed for train robbery alone.

Photos exist of the gruesome aftermath, the separated head still contained in the black hood and lying in front of the one-armed corpse. The Chronicle noted that the heart clearly continued beating for awhile. Then, in another strange twist, Black Jack’s head was sewn back on his body before burial at 2:30 p.m. that day in Clayton’s Boothill. One wonders how much effort they put into the job. No one was ever executed in all of Union County again.

Photos exist of the gruesome aftermath, the separated head still contained in the black hood and lying in front of the one-armed corpse. The Chronicle noted that the heart clearly continued beating for awhile. Then, in another strange twist, Black Jack’s head was sewn back on his body before burial at 2:30 p.m. that day in Clayton’s Boothill. One wonders how much effort they put into the job. No one was ever executed in all of Union County again. The first part of the quotation appears in the Santa Fe New Mexican, dated April 26, 1901, the day of the hanging, and it is directed toward Frank Harrington, the conductor who shot Black Jack's arm off. When Ketchum's lawyer was leaving his cell for presumably the last time, Black Jack told him, "Say, tell Harrington I'll meet him in hell for breakfast." This was after he'd requested to "be buried face down so Harrington can kiss my ass." The next morning, according to the New Mexican, he told Sheriff Garcia to "hurry up the hanging so he could get to hell in time for dinner."

The first part of the quotation appears in the Santa Fe New Mexican, dated April 26, 1901, the day of the hanging, and it is directed toward Frank Harrington, the conductor who shot Black Jack's arm off. When Ketchum's lawyer was leaving his cell for presumably the last time, Black Jack told him, "Say, tell Harrington I'll meet him in hell for breakfast." This was after he'd requested to "be buried face down so Harrington can kiss my ass." The next morning, according to the New Mexican, he told Sheriff Garcia to "hurry up the hanging so he could get to hell in time for dinner."

located on the east bank of the Rio Grande and close to El Camino Real, was a Spanish agricultural settlement known especially for its grapes. These grapes were crushed into wine reportedly shipped “all the way to Kansas.” The village was also a resting place and trading center for travelers on El Camino Real. Later, some residents became miners and worked in nearby

located on the east bank of the Rio Grande and close to El Camino Real, was a Spanish agricultural settlement known especially for its grapes. These grapes were crushed into wine reportedly shipped “all the way to Kansas.” The village was also a resting place and trading center for travelers on El Camino Real. Later, some residents became miners and worked in nearby

The “clean-up” was ostensibly part of a “desert restoration project” and, while I sure love the desert, I find this a little hard to believe. There is so much wide-open space in every direction out here that restoring this small area strikes me as bizarre. Not impossible though. On the other hand, “Ghost Towns and Mining Camps of New Mexico” stated in 1975: “Today what is left of Carthage is fast melting into oblivion.” Other than the impressive adobe ruins of the large home of a mine superintendent, John Hart, who left Carthage in the mid-1940’s, I have no idea what’s really been lost in the interim. At least the corpse of the small mining car above persists.

The “clean-up” was ostensibly part of a “desert restoration project” and, while I sure love the desert, I find this a little hard to believe. There is so much wide-open space in every direction out here that restoring this small area strikes me as bizarre. Not impossible though. On the other hand, “Ghost Towns and Mining Camps of New Mexico” stated in 1975: “Today what is left of Carthage is fast melting into oblivion.” Other than the impressive adobe ruins of the large home of a mine superintendent, John Hart, who left Carthage in the mid-1940’s, I have no idea what’s really been lost in the interim. At least the corpse of the small mining car above persists.

Then two major floods in 1929 washed away a big chunk of the town and the surrounding farmland. WWII lured away most remaining young men and A.H. Hilton’s original mercantile burnt around the same time, which, incidentally, pretty much coincided with Conrad's marriage to Zsa Zsa Gabor. However, Hilton’s wooden bar was saved and installed in the famous Owl Bar and Restaurant in 1945, where it is used to this day to support Tecate and green chile cheeseburgers. The Owl Bar itself was built by Brunswick Balke Collender Company. You might have used their bowling balls.

Then two major floods in 1929 washed away a big chunk of the town and the surrounding farmland. WWII lured away most remaining young men and A.H. Hilton’s original mercantile burnt around the same time, which, incidentally, pretty much coincided with Conrad's marriage to Zsa Zsa Gabor. However, Hilton’s wooden bar was saved and installed in the famous Owl Bar and Restaurant in 1945, where it is used to this day to support Tecate and green chile cheeseburgers. The Owl Bar itself was built by Brunswick Balke Collender Company. You might have used their bowling balls. while it’s well-known that all that’s left of what could be considered the original Hilton Hotel is its foundation, located across from the old post office (now a restored private residence), I have been unable to find a single picture of the site anywhere. So, as is my wont, I took my own. In fact, I took two. The concrete shown here and below is all that remains of the birthplace of one of the greatest hotel chains in the world, without which Paris Hilton might be living in a trailer out in the Socorro County desert. However, the original ballroom floor from the hotel was reportedly installed in the Wool Warehouse building in Magdalena. It must've been part of a remodeling job as that place was built in 1913. Can anyone get me in to have a look?!

while it’s well-known that all that’s left of what could be considered the original Hilton Hotel is its foundation, located across from the old post office (now a restored private residence), I have been unable to find a single picture of the site anywhere. So, as is my wont, I took my own. In fact, I took two. The concrete shown here and below is all that remains of the birthplace of one of the greatest hotel chains in the world, without which Paris Hilton might be living in a trailer out in the Socorro County desert. However, the original ballroom floor from the hotel was reportedly installed in the Wool Warehouse building in Magdalena. It must've been part of a remodeling job as that place was built in 1913. Can anyone get me in to have a look?!

Gamerco used to be just off U.S. Route 666, the

Gamerco used to be just off U.S. Route 666, the

Four stories tall and made of concrete--

Four stories tall and made of concrete--